Mut

| Mut | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Queen of the goddesses and lady of heaven | |||||

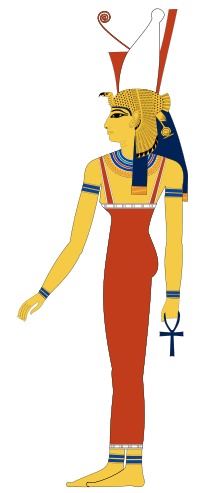

A contemporary image of goddess Mut, depicted as a woman wearing the double crown plus a royal vulture headdress, associating her with Nekhbet. | |||||

| Name in hieroglyphs |

| ||||

| Major cult center | Thebes | ||||

| Symbol | the Vulture | ||||

| Consort | Amun | ||||

| Parents | Ra | ||||

| Siblings | Sekhmet, Hathor, Ma'at and Bastet | ||||

| Offspring | Khonsu | ||||

Mut, which meant mother in the ancient Egyptian language,[1] was an ancient Egyptian mother goddess with multiple aspects that changed over the thousands of years of the culture. Alternative spellings are Maut and Mout. She was considered a primal deity, associated with the waters from which everything was born through parthenogenesis. She also was depicted as a woman with a head dress. The rulers of Egypt each supported her worship in their own way to emphasize their own authority and right to rule through an association with Mut.

Some of Mut's many titles included World-Mother, Eye of Ra, Queen of the Goddesses, Lady of Heaven, Mother of the Gods, and She Who Gives Birth, But Was Herself Not Born of Any.

Changes of mythological position

Mut was a title of the primordial waters of the cosmos, Naunet, in the Ogdoad cosmogony during what is called the Old Kingdom, the third through sixth dynasties, dated between 2,686 and 2,134 BCE. However, the distinction between motherhood and cosmic water later diversified and lead to the separation of these identities, and Mut gained aspects of a creator goddess, since she was the mother from which the cosmos emerged.

The hieroglyph for Mut's name, and for mother itself, was that of a vulture, which the Egyptians believed were very maternal creatures. Indeed, since Egyptian vultures have no significant differing markings between female and male of the species, being without sexual dimorphism, the Egyptians believed they were all females, who conceived their offspring by the wind herself, another parthenogenic concept.

Much later new myths held that since Mut had no parents, but was created from nothing; consequently, she could not have children and so adopted one instead.

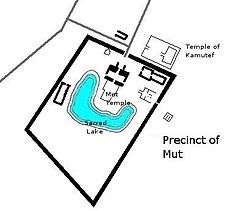

Making up a complete triad of deities for the later pantheon of Thebes, it was said that Mut had adopted Menthu, god of war. This choice of completion for the triad should have proved popular, but because the isheru, the sacred lake outside Mut's ancient temple in Karnak at Thebes, was the shape of a crescent moon, Khonsu, the moon god eventually replaced Menthu as Mut's adopted son.

Lower and upper Egypt both already had patron deities–Wadjet and Nekhbet–respectively, indeed they also had lioness protector deities–Bast and Sekhmet–respectively. When Thebes rose to greater prominence, Mut absorbed these warrior goddesses as some of her aspects. First, Mut became Mut-Wadjet-Bast, then Mut-Sekhmet-Bast (Wadjet having merged into Bast), then Mut also assimilated Menhit, who was also a lioness goddess, and her adopted son's wife, becoming Mut-Sekhmet-Bast-Menhit, and finally becoming Mut-Nekhbet.

Later in ancient Egyptian mythology deities of the pantheon were identified as equal pairs, female and male counterparts, having the same functions. In the later Middle Kingdom, when Thebes grew in importance, its patron, Amun also became more significant, and so Amaunet, who had been his female counterpart, was replaced with a more substantial mother-goddess, namely Mut, who became his wife. In that phase, Mut and Amun had a son, Khonsu, another moon deity.

The authority of Thebes waned later and Amun was assimilated into Ra. Mut, the doting mother, was assimilated into Hathor, the cow-goddess and mother of Horus who had become identified as Ra's wife. Subsequently, when Ra assimilated Atum, the Ennead was absorbed as well, and so Mut-Hathor became identified as Isis (either as Isis-Hathor or Mut-Isis-Nekhbet), the most important of the females in the Ennead (the nine), and the patron of the queen. The Ennead proved to be a much more successful identity and the compound triad of Mut, Hathor, and Isis, became known as Isis alone—a cult that endured into the 7th century A.D. and spread to Greece, Rome, and Britain.

Depictions

In art, Mut was pictured as a woman with the wings of a vulture, holding an ankh, wearing the united crown of Upper and Lower Egypt and a dress of bright red or blue, with the feather of the goddess Ma'at at her feet.

Alternatively, as a result of her assimilations, Mut is sometimes depicted as a cobra, a cat, a cow, or as a lioness as well as the vulture.

Before the end of the New Kingdom almost all images of female figures wearing the Double Crown of Upper and Lower Egypt were depictions of the goddess Mut, here labeled "Lady of Heaven, Mistress of All the Gods." The last image on this page shows the goddess's facial features which mark this as a work made sometime between late Dynasty XVIII and relatively early in the reign of Ramesses II (circa 1279-1213 B.C.).[2]

In Karnak

There are temples dedicated to Mut still standing in modern-day Egypt and Sudan, reflecting the widespread worship of her, but the center of her cult became the temple in Karnak. That temple had the statue that was regarded as an embodiment of her real ka. Her devotions included daily rituals by the pharaoh and her priestesses. Interior reliefs depict scenes of the priestesses, currently the only known remaining example of worship in ancient Egypt that was exclusively administered by women.

Usually the queen, who always carried the royal lineage among the rulers of Egypt, served as the chief priestess in the temple rituals. The pharaoh participated also and would become a deity after death. In the case when the pharaoh was female, records of one example indicate that she had her daughter serve as the high priestess in her place. Often priests served in the administration of temples and oracles where priestesses performed the traditional religious rites. These rituals included music and drinking.

The pharaoh Hatshepsut had the ancient temple to Mut at Karnak rebuilt during her rule in the Eighteenth Dynasty. Previous excavators had thought that Amenhotep III had the temple built because of the hundreds of statues found there of Sekhmet that bore his name. However, Hatshepsut, who completed an enormous number of temples and public buildings, had completed the work seventy-five years earlier. She began the custom of depicting Mut with the crown of both Upper and Lower Egypt. It is thought that Amenhotep III removed most signs of Hatshepsut, while taking credit for the projects she had built.

Hatshepsut was a pharaoh who brought Mut to the fore again in the Egyptian pantheon, identifying strongly with the goddess. She stated that she was a descendant of Mut. She also associated herself with the image of Sekhmet, as the more aggressive aspect of the goddess, having served as a very successful warrior during the early portion of her reign as pharaoh.

Later in the same dynasty, Akhenaten suppressed the worship of Mut as well as the other deities when he promoted the monotheistic worship of his sun god, Aten. Tutankhamun later re-established her worship and his successors continued to associate themselves with Mut afterward.

Ramesses II added more work on the Mut temple during the nineteenth dynasty, as well as rebuilding an earlier temple in the same area, rededicating it to Amun and himself. He placed it so that people would have to pass his temple on their way to that of Mut.

Kushite pharaohs expanded the Mut temple and modified the Ramesses temple for use as the shrine of the celebrated birth of Amun and Khonsu, trying to integrate themselves into divine succession. They also installed their own priestesses among the ranks of the priestesses who officiated at the temple of Mut.

The Greek Ptolemaic dynasty added its own decorations and priestesses at the temple as well and used the authority of Mut to emphasize their own interests.

Later, the Roman emperor Tiberius rebuilt the site after a severe flood and his successors supported the temple until it fell into disuse, sometime around the third century A.D. Some of the later Roman officials used the stones from the temple for their own building projects, often without altering the images carved upon them.

Personal piety

In the wake of Akhenaten's revolution, and the subsequent restoration of traditional beliefs and practices, the emphasis in personal piety moved towards greater reliance on divine, rather than human, protection for the individual. During the reign of Rameses II a follower of the goddess Mut donated all his property to her temple and recorded in his tomb:

And he [Kiki] found Mut at the head of the gods, Fate and fortune in her hand, Lifetime and breath of life are hers to command...I have not chosen a protector among men. I have not sought myself a protector among the great...My heart is filled with my mistress. I have no fear of anyone. I spend the night in quiet sleep, because I have a protector.[3]

References

- ↑ Velde, Herman te (2002). Mut. In D. B. Redford (Ed.), The ancient gods speak: A guide to Egyptian religion (pp. 238). New York: Oxford University Press, USA.

- ↑ "Relief of the Goddess Mut". http://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/3877/Relief_of_the_Goddess_Mut/set/b2a76d2df5ced4787e5bd55a53f53d33?referring-q=79.120. External link in

|website=(help); - ↑ "Of God and Gods", Jan Assmann, p. 83-84, University of Wisconsin Press, 2008, ISBN 0-299-22554-2

- Jennifer Pinkowski (October 2006). "Egypt's Ageless Goddess". ARCHAEOLOGY. Magazine. Archaeological Institute of America. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mut. |