Napata

Coordinates: 18°32′N 31°50′E / 18.53°N 31.84°E

| Napata in hieroglyphs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

Napata was a city-state of ancient Nubia on the west bank of the Nile River, at the site of modern Karima, Northern Sudan.

Early history

Napata was founded by Thutmose III in the 15th century BC after his conquest of Nubia. The nearby Jebel Barkal was taken to mark the southern border of the New Kingdom.

In 1075 BC, the High Priest of Amun at Thebes, capital of Egypt, became powerful enough to limit the power of the pharaoh over Upper Egypt. This was the beginning of the Third Intermediate Period (1075 BC-664 BC). The fragmentation of power in Egypt allowed the Nubians to regain autonomy. They founded a new kingdom, Kush, and centered it at Napata.

Napatan period

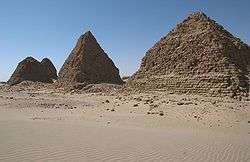

In 750 BC, Napata was a developed city, while Egypt was still suffering political instability. King Kashta ("the Cushite") profited from it, and attacked Upper Egypt. His policy was pursued by his successors Piye, and Shabaka (721–707 BC), who eventually brought the whole Nile Valley under Kushitic control in the second year of his reign. Shabaka also launched a monument-building policy in Egypt and Nubia. Overall, the Kushite kings ruled Upper Egypt for approximately one century and the whole Egypt for approximately 57 years, from 721 to 664 BC. They constitute the Twenty-fifth Dynasty in Manetho’s work, Aegyptiaca. The reunited Nile valley empire of the 25th dynasty was as large as it had been since the New Kingdom. The 25th dynasty ushered in a renaissance period for Ancient Egypt.[1] Religion, the arts, and architecture were restored to their glorious Old, Middle, and New Kingdom forms. Pharaohs, such as Taharqa, built or restored temples and monuments throughout the Nile valley, including at Memphis, Karnak, Kawa, Jebel Barkal, etc.[2] It was during the 25th dynasty that the Nile valley saw the first widespread construction of pyramids (many in modern Sudan) since the Middle Kingdom.[3][4][5] However, Pharaoh Taharqa's reign and that of his successor, (his cousin) Tanutamun, was filled with constant conflict with the Assyrians. In 664 BC the Assyrians laid the final blow, sacking Thebes and Memphis. The 25th dynasty ended with its rulers retreating to their spiritual homeland at Napata. It was there (at El-Kurru and Nuri) that all 25th dynasty pharaohs are buried under the first pyramids that the Nile valley had seen in centuries. The Napatan dynasty led to the Kingdom of Kush, which flourished in Napata and Meroe until at least the 2nd century AD.

Assyrian invasion and end of the Nubian dynasty

Around 670 BC, the Assyrian King Esarhaddon (681–669 BC) conquered Lower Egypt, but allowed local kingdoms in Lower Egypt to exist, in order to enlist them as his allies against the Kushite rulers of Upper Egypt, who had been accepted with reluctance.

When King Assurbanipal succeeded Esarhaddon, the Kushite king Taharqa convinced some rulers of Lower Egypt to break with Assyrians. However, Asshurbanipal overpowered the coalition and deported the Egyptian leaders to his capital, Niniveh. He appointed the Libyan chief Necho, ruler of Memphis and Sais. Necho I was the first king of the Saite Twenty-sixth Dynasty (664 BC-525 BC) of Egypt.

A new Kushite King Tantamani (664–653 BC) killed him the same year that Taharqa died, in 664 BC when Tantamani invaded Lower Egypt. However, Tantamani was unable to defeat the Assyrians who backed Necho’s son Psammetichus I. Tantamani eventually abandoned his attempt to conquer Lower Egypt and retreated to Napata. However, his authority over Upper Egypt was acknowledged until the 8th regnal year of his reign at Thebes (or 656 BC) when Psamtik I dispatched a naval fleet to Upper Egypt and succeeded in placing all of Egypt under his control.

Late Napatan kingdom

Napata remained the centre of the Kingdom of Kush for another two generations, from the 650s to 590 BC. Its economy was essentially based on gold, with 26th dynasty Egypt an important economic ally.

Napatan architecture, paintings, writing script, and other artistic and cultural forms were in Kush style. Egyptian burial customs were practised, including the resurrection of pyramid building. The Napatan dynasty and their successors built the first pyramids the Nile Valley had seen since the Middle Kingdom. Also, several Egyptian gods were worshipped. The most important god was Amun, a Theban deity, his temple was the most important at Napata, located at the foot of Jebel Barkal.[6]

After the Persian conquest of Egypt, Napata lost its economic influence. The Napatan region itself was desiccating, leading to less cattle and agriculture. A Persian raid had seriously affected Napata in 591 BC. Finally, Napata was losing its role of economic capital to Meroë. The Island of Meroë, the Peninsula formed by the Nile and the Atbara courses, was an area rich in iron, which was becoming an essential source of wealth. Meroe eventually became the capital of the kingdom of Kush, leading to the abandonment of Napata.

In 23 BC, the Roman prefect of Egypt invaded the kingdom after an initial attack by the queen of Meröe, razing Napata to the ground. In The Deeds of the Divine Augustus, Augustus claims that "a penetration was made as far as the town of Napata, which is next to Meroe..."[7]

Cultural references

Napata was mentioned in Verdi's Aida in Act, III when Amonastro uses Aida to learn where Radames will lead his army.

References

- ↑ Diop, Cheikh Anta (1974). The African Origin of Civilization. Chicago, Illinois: Lawrence Hill Books. pp. 219–221. ISBN 1-55652-072-7.

- ↑ Bonnet, Charles (2006). The Nubian Pharaohs. New York: The American University in Cairo Press. pp. 142–154. ISBN 978-977-416-010-3.

- ↑ Mokhtar, G. (1990). General History of Africa. California, USA: University of California Press. pp. 161–163. ISBN 0-520-06697-9.

- ↑ Emberling, Geoff (2011). Nubia: Ancient Kingdoms of Africa. New York: Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. pp. 9–11. ISBN 978-0-615-48102-9.

- ↑ Silverman, David (1997). Ancient Egypt. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 36–37. ISBN 0-19-521270-3.

- ↑ World Studies The Ancient World Chapter 3 Section 5 Pages 100, 101 and 102

- ↑ Augustus, "The Deeds of the Divine Augustus," Exploring the European Past: Texts & Images, Second Edition, ed. Timothy E. Gregory (Mason: Thomson, 2008), 119.

- Hornung, Erik.1999.History of Ancient Egypt, An Introduction. Translated from German by David Lorton. Grundzüge der ägyptischen Geschichte. New York, USA: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-8475-8.

- Grimal Nicolas.1992. A History of Ancient Egypt. Translated from French by Ian Shaw. Histoire de L’Egypte Ancienne. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-17472-9.

- Bianchi, Steven.1994. The Nubians. Connecticut, USA: Millbrook Press. ISBN 1-56294-356-1.

- Taylor, John. 1991. Egypt and Nubia. London, UK: The British Museum Press. ISBN 0-674-24130-4.

- UNESCO.2003.General History Of Africa Vol.2 Ancient Civilizations of Africa. Berkely, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0-435-94806-7.