North Korea–South Korea relations

|

|

North Korea |

South Korea |

|---|---|

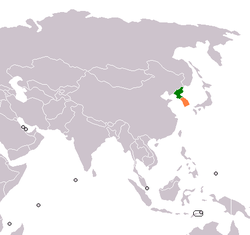

North Korea–South Korea relations (Hangul: 남북관계; Hanja: 南北關係; MR: Nambukkwan'gye) are the political, diplomatic, and military interactions between North Korea and South Korea, from the division of Korea in 1945 following World War II to today. These interactions have been dominated by the Korean conflict and efforts to resolve it and achieve reunification.

According to a 2014 BBC World Service Poll, 3% of South Koreans view North Korea's influence positively, with 91% expressing a negative view, making South Korea, after Japan, the country with the most negative feelings of North Korea in the world. However, a 2014 government funded survey found only 13% of South Koreans viewed North Korea as hostile, and 58% of South Koreans believed North Korea was a country they should cooperate with.[1]

Country comparison

| Common Name | North Korea | South Korea |

|---|---|---|

| Official Name | Democratic People's Republic of Korea | Republic of Korea |

| Coat of Arms |  |

|

| Flag |  |

|

| Population | 24,900,000 | 50,620,000 |

| Area | 120,540 km2 (46,540 sq mi) | 99,392 km2 (38,375 sq mi) |

| Population Density | 202/km2 (520/sq mi) | 491/km2 (1,270/sq mi) |

| Time zones | 1 (Pyongyang time) | 1 (Korean Standard Time) |

| Capital | Pyongyang | Seoul |

| Largest City | Pyongyang – 2,581,076 | Seoul – 10,464,051 (25,650,063 Metro) |

| Government | Unitary Juche one-party totalitarian absolute monarchy |

Unitary presidential democratic constitutional republic |

| Established | 9 September 1948 | 15 August 1948 |

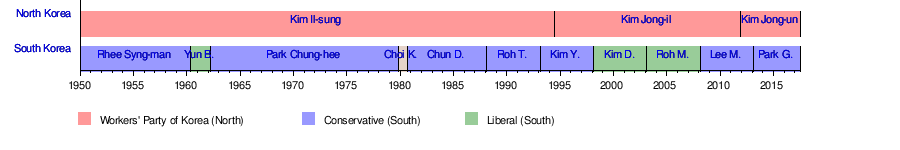

| First Leader | Kim Il-sung | Rhee Syng-man |

| Current Leader | Kim Jong-un (de facto) Kim Yong-nam (de jure) |

Park Geun-hye |

| Official languages | Korean | Korean |

| GDP (nominal) | US$12.4 billion ($506 per capita) | US$1.450 trillion ($28,739 per capita) |

Leaders of the two states

Background

Division of Korea

The Korean peninsula had been occupied by Japan from 1910. On August 9, 1945, in the closing days of World War Two, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan and advanced into Korea. Though the Soviet declaration of war had been agreed by the Allies at the Yalta Conference, the US government became concerned at the prospect of all of Korea falling under Soviet control. The US government therefore requested Soviet forces halt their advance at the 38th parallel north, leaving the south of the peninsula, including the capital, Seoul, to be occupied by the US. This was incorporated into General Order No. 1 to Japanese forces after the Surrender of Japan on August 15. On August 24, the Red Army entered Pyongyang and established a military government over Korea north of the parallel. American forces landed in the south on September 8 and established the United States Army Military Government in Korea.[2]

The Allies had originally envisaged a joint trusteeship which would usher Korea towards independence, but most Korean nationalists wanted independence immediately.[3] Meanwhile, the wartime co-operation between the Soviet Union and the US deteriorated as the Cold War took hold. Both occupying powers began promoting into positions of authority Koreans aligned with their side of politics and marginalizing their opponents. Many of these emerging political leaders were returning exiles with little popular support.[4][5] In North Korea, the Soviet Union supported Korean Communists. Kim Il-sung, who from 1941 had served in the Soviet Army, became the major political figure.[6] Society was centralized and collectivized, following the Soviet model.[7] Politics in the South was more tumultuous, but the strongly anti-Communist Syngman Rhee emerged as the most prominent politician.[8]

The US government took the issue to the United Nations, which led to the formation of the United Nations Temporary Commission on Korea (UNTCOK) in 1947. The Soviet Union opposed this move and refused to allow UNTCOK to operate in the North. UNTCOK organised a general election in the South, which was held on May 10, 1948.[9] The Republic of Korea was established with Syngman Rhee as President, and formally replaced the US military occupation on August 15. In North Korea, the Democratic People's Republic of Korea was declared on September 9, with Kim Il-sung, as prime minister. Soviet occupation forces left the North on December 10, 1948. US forces left the South the following year, though the US Korean Military Advisory Group remained to train the Republic of Korea Army.[10]

As a result, two antagonistic states emerged, with diametrically opposed political, economic, and social systems. Both opposing governments considered themselves to be the government of the whole of Korea, and both saw the division as temporary.[11][12] The DPRK proclaimed Seoul to be its official capital, a position not changed until 1972.[13]

Korean War

North Korea invaded the South on June 25, 1950, and swiftly overran most of the country. In September 1950 United Nations force, led by the United States, intervened to defend the South, and rapidly advanced into North Korea. As they neared the border with China, Chinese forces intervened on behalf of North Korea, shifting the balance of the war again. Fighting ended on July 27, 1953, with an armistice that approximately restored the original boundaries between North and South Korea.[14] Syngman Rhee refused to sign the armistice, but reluctantly agreed to abide by it.[15] The armistice inaugurated an official ceasefire but did not lead to a peace treaty. It established the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), a buffer zone between the two sides, that intersected the 38th parallel but did not follow it.[15]

Large numbers of people were displaced as a result of the war, and many families were divided by the reconstituted border. In 2007 it was estimated that around 750,000 people remained separated from immediate family members, and family reunions have long been a diplomatic priority.[16]

Cold War

Competition between North and South Korea became key to decision-making on both sides. For example, the construction of the Pyongyang Metro spurred the construction of one in Seoul.[17]

Tensions escalated in the late 1960s with a series of low-level armed clashes known as the Korean DMZ Conflict. During this time South Korea launched covert raids on the North.[18][19] On January 21, 1968, North Koreans commandos attacked the South Korean Blue House. On December 11, 1969, a South Korean airliner was hijacked.

During preparations for US President Nixon's visit to China in 1972, South Korean President Park Chung-hee initiated covert contact with the North's Kim Il-sung.[20] In August 1971, the first Red Cross talks between North and South Korea were held.[21] Many of the participants were really intelligence or party officials.[22] In May 1972, Lee Hu-rak, the director of the Korean CIA, secretly met with Kim Il-sung in Pyongyang. Kim apologized for the Blue House Raid, denying he had approved it.[23] In return, North Korea's deputy premier Pak Song-chol made a secret visit to Seoul.[24] On July 4, 1972, the North-South Joint Statement was issued. The statement announced the Three Principles of Reunification: first, reunification must be solved independently without interference from or reliance on foreign powers; second, reunification must be realized in a peaceful way without use of armed forces against each other; finally, reunification transcend the differences of ideologies and institutions to promote the unification of Korea as one ethnic group.[21][25] It also established the first "hotline" between the two sides.[26]

North Korea suspended talks in 1973 after the kidnapping of South Korean opposition leader Kim Dae-jung by the Korean CIA.[20][27] Talks restarted, however, and between 1973 and 1975 there were 10 meetings of the North-South Coordinating Committee at Panmunjom.[28]

In the late 1970s, US President Jimmy Carter hoped to achieve peace in Korea. However, his plans were derailed because of the unpopularity of his proposed withdrawal of troops.[29]

In 1983, a North Korean proposal for three-way talks with the United States and South Korea coincided with the Rangoon assassination attempt against the South Korean President.[30] This contradictory behavior has never been explained.[31]

In September 1984, North Korea's Red Cross sent emergency supplies to the South after severe floods.[20] Talks resumed, resulting in the first reunion of separated families in 1985, as well as a series of cultural exchanges.[20][32] Goodwill dissipated with the staging of the US-South Korean military exercise, Team Spirit, in 1986.[33]

Reconciliation and antagonism

When Seoul was chosen to host the 1988 Summer Olympics, North Korea tried to arrange a boycott by its Communist allies or a joint hosting of the Games.[34] This failed, and the bombing of Korean Air Flight 858 in 1987 was seen as North Korea's response.[35] However, at the same time, amid a global thawing of the Cold War, the newly elected South Korean President Roh Tae-woo launched a diplomatic initiative known as Nordpolitik. This proposed the interim development of a "Korean Community", which was similar to a North Korean proposal for a confederation.[36] From September 4 to 7, 1990, the high-level talks were held in Seoul, at the same time that the North was protesting about the Soviet Union normalizing relations with the South. These talks led in 1991 to the Agreement on Reconciliation, Non-Aggression, Exchanges and Cooperation and the Joint Declaration on the Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.[37][38] This coincided with the admission of both North and South Korea into the United Nations.[39] Meanwhile, on March 25, 1991, a unified Korean team first used the Korean Unification Flag at the World Table Tennis Competition in Japan, and on May 6, 1991, a unified team competed at the World Youth Football Competition in Portugal.

There were limits to the thaw in relations, however. In 1989 a South Korean student activist who participated in the World Youth Festival in Pyongyang was jailed on her return.[39]

The goodwill generated began to dissipate with disagreements over North Korea's nuclear program which led in 1994 to the Agreed Framework between the US and North Korea.[40] At the same time, the end of the Cold War brought economic crisis to North Korea and led to expectations that reunification was imminent.[41][42] North Koreans began to flee to the South in increasing numbers. According to official statistics there were 561 defectors living in South Korea in 1995, and over 10,000 in 2007.[43]

In 1998, South Korean President Kim Dae-jung announced a Sunshine Policy towards North Korea. Despite a naval clash in 1999, this led in June, 2000, to the first Inter-Korean Summit, between Kim Dae-jung and Kim Jong-il.[44] As a result, Kim Dae-jung was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.[45] The summit was followed in August by a family reunion.[32] In September, the North and South Korean teams marched together at the Sydney Olympics.[46] Trade increased to the point where South Korea became North Korea's largest trading partner.[47] Starting in 1998, the Mount Kumgang Tourist Region was developed as a joint venture between the North Korean government and Hyundai.[48] In 2003, the Kaesong Industrial Region was established to allow South Korean businesses to invest in the North.[49]

US President George W Bush, however, did not support the Sunshine Policy and in 2002 branded North Korea as a member of an Axis of Evil.[50][51]

Continuing concerns about North Korea's potential to develop nuclear missiles led in 2003 to the six-party talks that included North Korea, South Korea, the USA, Russia, China, and Japan.[52] In 2006, however, North Korea resumed testing missiles and on October 9 conducted its first nuclear test.[53]

The June 15, 2000 Joint Declaration that the two leaders signed during the first South-North summit stated that they would hold the second summit at an appropriate time. It was originally envisaged that the second summit would be held in South Korea, but that did not eventuate. South Korean President Roh Moo-hyun walked across the Korean Demilitarized Zone on October 2, 2007 and travelled on to Pyongyang for talks with Kim Jong-il.[54][55][56][57] The two sides reaffirmed the spirit of the June 15 Joint Declaration and had discussions on various issues related to realizing the advancement of South-North relations, peace on the Korean Peninsula, common prosperity of the people and the unification of Korea. On October 4, 2007, South Korean President Roh Moo-hyun and North Korean leader Kim Jong-il signed the peace declaration. The document called for international talks to replace the Armistice which ended the Korean War with a permanent peace treaty.[58]

During this period, the political developments were reflected in art. The films, Shiri in 1999 and Joint Security Area in 2000, gave sympathetic representations of North Koreans.[59][60]

After the Sunshine Policy

The Sunshine Policy was formally abandoned by the new South Korean President Lee Myung-bak in 2010.[61]

On March 26, 2010, the 1,500-ton ROKS Cheonan with a crew of 104, sank off Baengnyeong Island in the Yellow Sea. Seoul said there was an explosion at the stern, and was investigating whether a torpedo attack was the cause. Out of 104 sailors, 46 died and 58 were rescued. South Korean President Lee Myung-bak convened an emergency meeting of security officials and ordered the military to focus on rescuing the sailors.[62][63] On May 20, 2010, a team of international researchers published results claiming that the sinking had been caused by a North Korean torpedo; North Korea rejected the findings.[64] South Korea agreed with the findings from the research group and President Lee Myung-bak declared afterwards that Seoul would cut all trade with North Korea as part of measures primarily aimed at striking back at North Korea diplomatically and financially.[65] North Korea denied all such allegations and responded by severing ties between the countries and announced it abrogated the previous non-aggression agreement.[66]

On November 23, North Korea's artillery fired at South Korea's Yeonpyeong island in the Yellow Sea and South Korea returned fire. Two South Korean marines and two civilians were killed, more than a dozen were wounded, including three civilians. About 10 North Koreans were believed to be killed; however the North Korean government denies this. The town was evacuated and South Korea warned of stern retaliation, with President Lee Myung-bak ordering the destruction of a nearby North Korea missile base if further provocation should occur.[67] The official North Korean news agency, KCNA, stated that North Korea only fired after the South had "recklessly fired into our sea area".[68]

In 2011 it was revealed that North Korea abducted four high-ranking South Korean military officers in 1999.[69]

On December 12, North Korea launched the Kwangmyŏngsŏng-3 Unit 2, a scientific and technological satellite, and it reached orbit.[70][71][72] The United States moved warships to the region.[73] January–September 2013 saw an escalation of tensions between North Korea and South Korea, the United States, and Japan that began because of United Nations Security Council Resolution 2087, which condemned North Korea for the launch of Kwangmyŏngsŏng-3 Unit 2. The crisis was marked by extreme escalation of rhetoric by the new North Korean administration under Kim Jong-un and actions suggesting imminent nuclear attacks against South Korea, Japan, and the United States.[74]

On March 24, 2014, a crashed North Korean drone was found near Paju, the onboard cameras contained pictures of the Blue House and military installations near the DMZ. On March 31, following an exchange of artillery fire into the waters of the NLL, a North Korean drone was found crashed on Baengnyeongdo.[75][76] On September 15, wreckage of a suspected North Korean drone was found by a fisherman in the waters near Baengnyeongdo, the drone was reported to be similar to one of the North Korean drones which had crashed in March 2014.[77]

On January 1, 2015, Kim Jong-un, in his New Year's address to the country, stated that he was willing to resume higher-level talks with the South.[78]

In the first week of August 2015, a mine went off at the DMZ, wounding two South Korean soldiers. The South Korean government accused the North of planting the mine, which the North denied. Since then South Korea started propaganda broadcasts to the North.[79]

On August 20, 2015, North Korea fired a shell on the city of Yeoncheon. South Korea launched several artillery rounds in response. Although there were no casualties, it caused the evacuation of an area of the west coast of South Korea and forced others to head for bunkers.[80] The shelling caused both countries to adopt pre-war statuses and a talk that was held by high level officials in the Panmunjeom to relieve tensions on August 22, 2015, and the talks carried over to the next day.[81] Nonetheless while talks were going on, North Korea deployed over 70 percent of their submarines, which increased the tension once more on August 23, 2015.[82] Talks continued into the next day and finally concluded on August 25 when both parties reached an agreement and military tensions were eased.

On September 9, 2016, North Korea carried out its fifth nuclear test as part of the state's 68th anniversary since its founding.[83] South Korea responded with a plan to assassinate Kim Jong-un.[84]

See also

- Korean conflict

- Censorship in North Korea

- Censorship in South Korea

- June 15th North–South Joint Declaration

- Korean Demilitarized Zone

- Korean reunification

- Northern Limit Line

- List of border incidents involving North Korea

- North Korea–South Korea football rivalry

References

- ↑ Zachary Keck (30 May 2014). "South Koreans View North Korea as Cooperative Partner". The Diplomat. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ↑ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 50. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- ↑ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 59. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- ↑ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. pp. 50–51, 59. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- ↑ Cumings, Bruce (2005). Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 194–195. ISBN 0-393-32702-7.

- ↑ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 56. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- ↑ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 68. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- ↑ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. pp. 66, 69. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- ↑ Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-07456-3357-2.

- ↑ Cumings, Bruce (2005). Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 255–256. ISBN 0-393-32702-7.

- ↑ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 72. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- ↑ Cumings, Bruce (2005). Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 505–506. ISBN 0-393-32702-7.

- ↑ Hyung Gu Lynn (2007). Bipolar Orders: The Two Koreas since 1989. Zed Books. p. 158.

- ↑ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 71. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- 1 2 Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-07456-3357-2.

- ↑ Hyung Gu Lynn (2007). Bipolar Orders: The Two Koreas since 1989. Zed Books. p. 10.

- ↑ Hunter, Helen-Louise (1999). Kim Il-song's North Korea. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. p. 189. ISBN 0-275-96296-2.

- ↑ Lee Tae-hoon (7 February 2011). "S. Korea raided North with captured agents in 1967". The Korea Times. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ↑ "Minutes of Washington Special Actions Group Meeting, Washington, August 25, 1976, 10:30 a.m.". Office of the Historian, U.S. Department of State. 25 August 1976. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

Clements: I like it. It doesn't have an overt character. I have been told that there have been 200 other such operations and that none of these have surfaced. Kissinger: It is different for us with the War Powers Act. I don't remember any such operations.

- 1 2 3 4 Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-07456-3357-2.

- 1 2 김영호. 사실로 본 한국 근현대사. 2nd ed. 서울:황금알, 2011. Print.

- ↑ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. p. 12. ISBN 9780465031238.

- ↑ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. pp. 18–19. ISBN 9780465031238.

- ↑ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. p. 19. ISBN 9780465031238.

- ↑ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. pp. 19–20. ISBN 9780465031238.

- ↑ Robinson, Michael E (2007). Korea's Twentieth-Century Odyssey. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 179. ISBN 978-0-8248-3174-5.

- ↑ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. p. 35. ISBN 9780465031238.

- ↑ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. p. 36. ISBN 9780465031238.

- ↑ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. pp. 83–86. ISBN 9780465031238.

- ↑ Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-07456-3357-2.

- ↑ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. p. 113. ISBN 9780465031238.

- 1 2 Choe, Sang-Hun (Feb 20, 2014). "Amid Hugs and Tears, Korean Families Divided by War Reunite". The New York Times. Archived from the original on Feb 21, 2014. Retrieved Jan 12, 2015.

- ↑ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. pp. 118–119. ISBN 9780465031238.

- ↑ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. p. 142–143. ISBN 9780465031238.

- ↑ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 165. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- ↑ Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-07456-3357-2.

- ↑ Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. pp. 49, 66–67. ISBN 978-07456-3357-2.

- ↑ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. pp. 165–169, 173–175. ISBN 9780465031238.

- 1 2 Hyung Gu Lynn (2007). Bipolar Orders: The Two Koreas since 1989. Zed Books. p. 160.

- ↑ Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. pp. 68, 76. ISBN 978-07456-3357-2.

- ↑ Cumings, Bruce (2005). Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 509. ISBN 0-393-32702-7.

- ↑ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. pp. 173–176. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- ↑ Hyung Gu Lynn (2007). Bipolar Orders: The Two Koreas since 1989. Zed Books. p. 164.

- ↑ Robinson, Michael E (2007). Korea's Twentieth-Century Odyssey. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 165,180. ISBN 978-0-8248-3174-5.

- ↑ Hyung Gu Lynn (2007). Bipolar Orders: The Two Koreas since 1989. Zed Books. p. 161.

- ↑ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 179. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- ↑ Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-07456-3357-2.

- ↑ Robinson, Michael E (2007). Korea's Twentieth-Century Odyssey. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 179–180. ISBN 978-0-8248-3174-5.

- ↑ Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. pp. 107–108. ISBN 978-07456-3357-2.

- ↑ Cumings, Bruce (2005). Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 504. ISBN 0-393-32702-7.

- ↑ Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. p. 112. ISBN 978-07456-3357-2.

- ↑ Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. pp. 124–125. ISBN 978-07456-3357-2.

- ↑ Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. pp. 132–133. ISBN 978-07456-3357-2.

- ↑ Korean leaders in historic talks, BBC, Tuesday, 2 October 2007, 10:14 GMT

- ↑ In pictures: Historic crossing, BBC, 2 October 2007, 10:15 GMT

- ↑ Mixed feelings over Koreas summit, BBC, 2 October 2007, 10:17 GMT

- ↑ Kim greets Roh in Pyongyang before historic summit, CNN. Retrieved 2 October 2007.

- ↑ Korean leaders issue peace call, BBC, 4 October 2007, 9:27 GMT

- ↑ Robinson, Michael E (2007). Korea's Twentieth-Century Odyssey. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 184–185. ISBN 978-0-8248-3174-5.

- ↑ Hyung Gu Lynn (2007). Bipolar Orders: The Two Koreas since 1989. Zed Books. p. 163.

- ↑ South Korea Formally Declares End to Sunshine Policy, Voice of America, 18 November 2010

- ↑ Geopolitical Weekly

- ↑ "'Blast' sinks S Korea navy ship". BBC News. March 26, 2010.

- ↑ "Anger at North Korea over sinking". BBC News. 2010-05-20. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ↑ Clinton: Koreas security situation 'precarious', by Matthew Lee, Associated Press, 24-05-2010

- ↑ Text from North Korea statement, by Jonathan Thatcher, Reuters, 25-05-2010

- ↑ "(LEAD) S. Korea vows 'stern retaliation' against N. Korea's attacks" (in Korean). English.yonhapnews.co.kr. 2010-11-23. Retrieved 2013-04-05.

- ↑ McDonald, Mark (November 23, 2010). "North and South Korea Exchange Fire, Killing Two". The New York Times. Retrieved November 23, 2010.

- ↑ Kim, Rahn (2011-05-20). "North Korea abducted 4 South Korean military officers'". The Korea Times. Retrieved 2011-07-31.

- ↑ "KCST Spokesman on Launching Time of Satellite". Kcna.co.jp. 2012-12-08. Retrieved 2013-04-05.

- ↑ "DPRK Succeeds in Satellite Launch". Kcna.co.jp. 2012-12-12. Retrieved 2013-04-05.

- ↑ "KCNA Releases Report on Satellite Launch". Kcna.co.jp. 2012-12-12. Retrieved 2013-04-05.

- ↑ "US moves warships to track North Korea rocket launch". Bbc.co.uk. 2012-12-07. Retrieved 2013-04-05.

- ↑ "In Focus North Korea's Nuclear Threats".

- ↑ "Mystery drones found in Baengnyeong, Paju". JoongAng Daily. 2 April 2014. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ "South Korea: Drones 'confirmed as North Korean'". BBC News. 8 May 2014. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ "South Korea finds wreckage in sea of suspected North Korean drone". Reuters. 15 September 2014. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ Yahoo! News

- ↑ "Land Mine Blast South Korea Threatens North with Retaliation".

- ↑ South Korea evacuation after shelling on western border

- ↑ "Rival Koreas Restart Talks, Pull Back from Brink for Now".

- ↑ "North Korea Deploys Submarines while Talks with Seoul Resume".

- ↑ Kim, Jack (10 September 2016). "South Korea says North's nuclear capability 'speeding up', calls for action". Reuters. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ↑ Hancocks, Paula (23 September 2016). "South Korea reveals it has a plan to assassinate Kim Jong Un". CNN. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

External links

- Inter-Korean Relations: Past, Present and Future (Introduction) - cfr.org

- Inter-Korean Relations: Past, Present and Future (Panel 1) - cfr.org

- ROK and Inter-Korean relations

- Eating the Oxen of the Sun – The Odyssey of Unification

- Inter-Korean tensions: ideology first, at any cost? by Alain Nass (expert on Asia and Korea), Asia & Pacific Network, October 2011