Nova

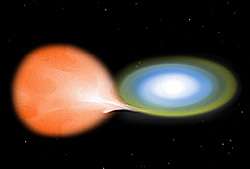

A nova (plural novae or novas) is a cataclysmic nuclear explosion on a white dwarf, which causes a sudden brightening of the star. Novae are not to be confused with other brightening phenomena such as supernovae or luminous red novae. Novae are thought to occur on the surface of a white dwarf in a binary system when they are sufficiently near to one another, allowing material (mostly hydrogen) to be pulled from the companion star's surface onto the white dwarf. The nova is the result of the rapid fusion of the accreted hydrogen on the surface of the star, commencing a runaway fusion reaction.

Development

The development begins with two main sequence stars in a binary relation. One of the two evolves into a red giant leaving its remnant white dwarf core in orbit with the remaining star. The second star—which may be either a main sequence star, or an aging giant one as well—begins to shed its envelope onto its white dwarf companion when it overflows its Roche lobe. As a result, the white dwarf will steadily accrete matter from the companion's outer atmosphere; the white dwarf consists of degenerate matter, so the accreted hydrogen does not inflate as its temperature increases. Rapid, uncontrolled fusion occurs when the temperature of this accreted layer reaches ~20 million Kelvins, initiating a burn via the CNO cycle.[1]

While hydrogen fusion can occur in a stable manner on the surface of the white dwarf for a narrow range of accretion rates, for most binary system parameters the hydrogen burning is thermally unstable and rapidly converts a large amount of the hydrogen into other heavier elements in a runaway reaction,[2] liberating an enormous amount of energy, blowing the remaining gases away from the white dwarf's surface and producing an extremely bright outburst of light. The rise to peak brightness can be very rapid or gradual and is related to the speed class of the nova; after the peak, the brightness declines steadily.[3] The time taken for a nova to decay by 2 or 3 magnitudes from maximum optical brightness is used to classify a nova via its speed class. A fast nova will typically take less than 25 days to decay by 2 magnitudes and a slow nova will take over 80 days.[4]

In spite of their violence, the amount of material ejected in novae is usually only about 1⁄10,000 of a solar mass, quite small relative to the mass of the white dwarf. Furthermore, only five percent of the accreted mass is fused during the power outburst.[2] Nonetheless, this is enough energy to accelerate nova ejecta to velocities as high as several thousand kilometers per second—higher for fast novae than slow ones—with a concurrent rise in luminosity from a few times solar to 50,000–100,000 times solar.[2][5] In 2010 scientists using NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope were surprised to discover, for the first time, that a nova can also emit gamma-rays (>100 MeV).[6]

A white dwarf can potentially generate multiple novae over time as additional hydrogen continues to accrete onto its surface from its companion star. An example is RS Ophiuchi, which is known to have flared six times (in 1898, 1933, 1958, 1967, 1985, and 2006). Eventually, the white dwarf could explode as a Type Ia supernova if it approaches the Chandrasekhar limit.

Occasionally a nova is bright enough and close enough to be conspicuous to the unaided eye. The brightest recent example was Nova Cygni 1975. This nova appeared on 29 August 1975, in the constellation Cygnus about five degrees north of Deneb and reached magnitude 2.0 (nearly as bright as Deneb). The most recent were V1280 Scorpii, which reached magnitude 3.7 on 17 February 2007, and Nova Delphini 2013. Nova Centauri 2013 was discovered 2 December 2013 and is so far the brightest nova of this millennium reaching magnitude 3.3 .

Helium novae

A helium nova (or helium flash) is a proposed category of nova explosion that lacks hydrogen lines in the spectrum. This may be caused by the explosion of a helium shell on a white dwarf. It was proposed by Kato, Saio, and Hachisu in 1989. The first candidate helium nova to be observed was V445 Puppis in 2000.[7] Since then, four other novae explosions have been proposed as helium novae.[8]

Occurrence rate and astrophysical significance

Astronomers estimate that the Milky Way experiences roughly 30 to 60 novae per year, with a likely rate of about 40.[2] The number of novae discovered in the Milky Way each year is much lower, about 10.[9] Roughly 25 novae brighter than about magnitude 20 are discovered in the Andromeda Galaxy each year and smaller numbers are seen in other nearby galaxies.[10]

Spectroscopic observation of nova ejecta nebulae has shown that they are enriched in elements such as helium, carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, neon, and magnesium.[2] The contribution of novae to the interstellar medium is not great; novae supply only 1⁄50 as much material to the Galaxy as do supernovae, and only 1⁄200 as much as red giant and supergiant stars.[2]

Recurrent novae like RS Ophiuchi (those with periods on the order of decades) are rare. Astronomers theorize however that most, if not all, novae are recurrent, albeit on time scales ranging from 1,000 to 100,000 years.[11] The recurrence interval for a nova is less dependent on the white dwarf's accretion rate than on its mass; with their powerful gravity, massive white dwarfs require less accretion to fuel an outburst than lower-mass ones.[2] Consequently, the interval is shorter for high-mass white dwarfs.[2]

Subtypes

Novae are classified according to the light curve development speed, so in

- NA: Fast novae, with a rapid brightness increase, followed by a brightness decline of 3 magnitudes — to about 1⁄16 brightness — within 100 days.[12]

- NB: Slow novae, with a 3 magnitudes decline in 150 days or more.

- NC: Very slow novae, staying at maximum light for a decade or more, fading very slowly. It is possible that NC type novae are objects differing physically very much from normal novae, for example planetary nebulae in formation, exhibiting Wolf-Rayet star like features.

- NR/RN: Recurrent novae, novae with two or more outbursts separated by 10–80 years have been observed.[13]

Etymology

During the 16th century, astronomer Tycho Brahe observed the supernova SN 1572 in the constellation Cassiopeia. He described it in his book De nova stella (Latin for "concerning the new star"), giving rise to the name nova. In this work he argued that a nearby object should be seen to move relative to the fixed stars, and that the nova had to be very far away. Though this was a supernova and not a classical nova, the terms were considered interchangeable until the 1930s.[2]

Novae as distance indicators

Novae have some promise for use as standard candle measurements of distances. For instance, the distribution of their absolute magnitude is bimodal, with a main peak at magnitude −8.8, and a lesser one at −7.5. Novae also have roughly the same absolute magnitude 15 days after their peak (−5.5). Comparisons of nova-based distance estimates to various nearby galaxies and galaxy clusters with those done with Cepheid variable stars have shown them to be of comparable accuracy.[14]

Bright novae since 1890

Over 53 novae have been registered since 1890.

Recurrent novae

There are ten known galactic recurrent novae.[15] The recurrent nova typically brightens by about 8.6 magnitude, whereas a classic nova brightens by more than 12 magnitude.[15] The ten known recurrent novae are listed below.

| Full name |

Discoverer |

Magnitude range |

Days to drop 3 magnitude from peak |

Known outburst years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CI Aquilae | K.Reinmuth | 8.6-16.3 | ? | 2000, 1941, 1917 |

| V394 Coronae Australis | L.E.Erro | 7.2-19.7 | ? | 1987, 1949 |

| T Coronae Borealis | J.Birmingham | 2.5–10.8 | 6 | 1946, 1866 |

| IM Normae | I.E.Woods | 8.5-18.5 | ? | 2002, 1920 |

| RS Ophiuchi | W.Fleming | 4.8–11 | 14 | 2006, 1985, 1967, 1958, 1933, 1898 |

| V4287 Ophiuchi | K.Takamizawa | 9.5-17.5 | ? | 1998, 1900 |

| T Pyxidis | H.Leavitt | 6.4–15.5 | 62 | 2011, 1967, 1944, 1920, 1902, 1890 |

| V3890 Sagittarii | H.Dinerstein | 8.1-18.4 | ? | 1990, 1962 |

| U Scorpii | N.R.Pogson | 7.5–17.6 | 2.6 | 2010, 1999, 1987, 1979, 1936, 1917, 1906, 1863 |

| V745 Scorpii | L.Plaut | 9.4-19.3 | ? | 2014, 1989, 1937 |

Extragalactic novae

.jpg)

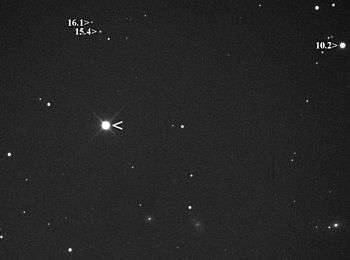

Novae in the Andromeda galaxy (M31) are relatively common.[10] There are roughly a couple dozen novae discovered (brighter than about apparent magnitude 20) in M31 each year.[10] The Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams (CBAT) tracks novae in M31, M33, and M81.[16]

See also

References

- ↑ M.J. Darnley; et al. (10 February 2012). "On the Progenitors of Galactic Novae". The Astrophysical Journal. 746 (61). arXiv:1112.2589

. Bibcode:2012ApJ...746...61D. doi:10.1088/0004-637x/746/1/61. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

. Bibcode:2012ApJ...746...61D. doi:10.1088/0004-637x/746/1/61. Retrieved 10 February 2015. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Prialnik, Dina (2001). "Novae". In Paul Murdin. Encyclopedia of Astronomy and Astrophysics. Institute of Physics Publishing/Nature Publishing Group. pp. 1846–1856. ISBN 1-56159-268-4.

- ↑ AAVSO Variable Star Of The Month: May 2001: Novae

- ↑ Warner, Brian (1995). Cataclysmic Variable Stars. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-41231-5.

- ↑ Zeilik, Michael (1993). Conceptual Astronomy. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-50996-5.

- ↑ JPL/NASA (12 August 2010). "Fermi detects 'shocking' surprise from supernova's little cousin". PhysOrg. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

- ↑ Kato, Mariko; Hachisu, Izumi (December 2003). "V445 Puppis: Helium Nova on a Massive White Dwarf". The Astrophysical Journal. 598 (2): L107–L110. arXiv:astro-ph/0310351

. Bibcode:2003ApJ...598L.107K. doi:10.1086/380597.

. Bibcode:2003ApJ...598L.107K. doi:10.1086/380597. - ↑ Rosenbush, A. E. (17–21 September 2007). Klaus Werner; Thomas Rauch, eds. "List of Helium Novae". proceedings, Hydrogen-Deficient Stars ASP Conference Series. Eberhard Karls University, Tübingen, Germany (published July 2008). 391. Bibcode:2008ASPC..391..271R.

- ↑ "CBAT List of Novae in the Milky Way". IAU Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams.

- 1 2 3 "M31 (Apparent) Novae Page". IAU Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams. Retrieved 2009-02-24.

- ↑ Seeds, Michael A. (1998). Horizons: Exploring the Universe (5th ed.). Wadsworth Publishing Company. p. 194. ISBN 0-534-52434-6.

- ↑ "Ritter Cataclysmic Binaries Catalog (7th Edition, Rev. 7.13)". High Energy Astrophysics Science Archive Research Center. 31 March 2010. Retrieved 2010-09-25.

- ↑ GCVS' vartype.txt at VizieR

- ↑ Robert, Gilmozzi; Della Valle, Massimo (2003). "Novae as Distance Indicators". In Alloin, D.; Gieren, W. Stellar Candles for the Extragalactic Distance Scale. Springer. pp. 229–241. ISBN 3-540-20128-9.

- 1 2 Schaefer, Bradley E. (2009). "Comprehensive Photometric Histories of All Known Galactic Recurrent Novae". arXiv:0912.4426

[astro-ph.SR].

[astro-ph.SR]. - ↑ Bishop, David. "Extragalactic Novae". International Supernovae Network. Retrieved 2010-09-11.

Further reading

- Payne-Gaposchkin, C. (1957). The Galactic Novae. North Holland Publishing Co.

- Hernanz, M.; Josè, J. (2002). Classical Nova Explosions. American Institute of Physics.

- Bode, M.F.; Evans, E. (2008). Classical Novae. Cambridge University Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nova. |

- Schaefer (2009). "Comprehensive Photometric Histories of All Known Galactic Recurrent Novae". arXiv:0912.4426

[astro-ph.SR].

[astro-ph.SR]. - Shafter; et al. (2011). "A Spectroscopic and Photometric Survey of Novae in M31". arXiv:1104.0222

[astro-ph.SR].

[astro-ph.SR]. - General Catalog of Variable Stars, Sternberg Astronomical Institute, Moscow

- AAVSO Variable Star of the Month. Novae: May 2001

- Extragalactic Novae