Obligate anaerobe

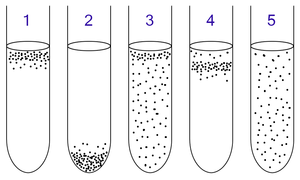

1: Obligate aerobes need oxygen because they cannot ferment or respire anaerobically. They gather at the top of the tube where the oxygen concentration is highest.

2: Obligate anaerobes are poisoned by oxygen, so they gather at the bottom of the tube where the oxygen concentration is lowest.

3: Facultative anaerobes can grow with or without oxygen because they can metabolise energy aerobically or anaerobically. They gather mostly at the top because aerobic respiration generates more ATP than either fermentation or anaerobic respiration.

4: Microaerophiles need oxygen because they cannot ferment or respire anaerobically. However, they are poisoned by high concentrations of oxygen. They gather in the upper part of the test tube but not the very top.

5: Aerotolerant organisms do not require oxygen and cannot utilise it even if present; they metabolise energy anaerobically. Unlike obligate anaerobes, however, they are not poisoned by oxygen. They can be found evenly spread throughout the test tube.

Obligate anaerobes are microorganisms killed by normal atmospheric concentrations of oxygen (20.95% O2).[1][2] Oxygen tolerance varies between species, some capable of surviving in up to 8% oxygen, others losing viability unless the oxygen concentration is less than 0.5%.[3] An important distinction needs to be made here between the obligate anaerobes and the microaerophiles. Microaerophiles, like the obligate anaerobes, are damaged by normal atmospheric concentrations of oxygen. However, microaerophiles metabolise energy aerobically, and obligate anaerobes metabolise energy anaerobically. Microaerophiles therefore require oxygen (typically 2-10% O2) for growth. Obligate anaerobes do not.[1][3][4]

Oxygen sensitivity

The oxygen sensitivity of obligate anaerobes has been attributed to a combination of factors:

- Because molecular oxygen contains two unpaired electrons in its outer orbital, it is readily reduced to superoxide (O−

2) and hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2) within cells.[1] Aerobic organisms produce superoxide dismutase and catalase to detoxify these products, but obligate anaerobes produce these enzymes in very small quantities, or not at all.[1][2][3][5] (The variability in oxygen tolerance of obligate anaerobes (<0.5 to 8% O2) is thought to reflect the quantity of superoxide dismutase and catalase being produced.[2][3]) - Dissolved oxygen increases the redox potential of a solution, and high redox potential inhibits the growth of some obligate anaerobes.[3][5][6] For example, methanogens grow at a redox potential lower than -0.3 V.[6]

- Sulfide is an essential component of some enzymes, and molecular oxygen oxidizes this to form disulfide, thus inactivating certain enzymes (e.g. nitrogenase). Organisms may not be able to grow with these essential enzymes deactivated.[1][5][6]

- Growth may be inhibited due to a lack of reducing equivalents for biosynthesis, because electrons are exhausted in reducing oxygen.[6]

Energy metabolism

Obligate anaerobes metabolise energy by anaerobic respiration or fermentation. In aerobic respiration, the pyruvate generated from glycolysis is converted to acetyl-CoA. This is then broken down via the TCA cycle and electron transport chain. Anaerobic respiration differs from aerobic respiration in that it uses an electron acceptor other than oxygen in the electron transport chain. Examples of alternative electron acceptors include sulfate, nitrate, iron, manganese, mercury, and carbon monoxide.[4]

Fermentation differs from anaerobic respiration in that the pyruvate generated from glycolysis is broken down without the involvement of an electron transport chain (i.e. there is no oxidative phosphorylation). Numerous fermentation pathways exist e.g. lactic acid fermentation, mixed acid fermentation, 2-3 butanediol fermentation.[4]

The energy yield of anaerobic respiration and fermentation (i.e. the number of ATP molecules generated) is less than in aerobic respiration.[4] This is why facultative anaerobes, which can metabolise energy both aerobically and anaerobically, preferentially metabolise energy aerobically. This is observable when facultative anaerobes are cultured in thioglycollate broth.[1]

Examples

Examples of obligately anaerobic bacterial genera include Actinomyces, Bacteroides, Clostridium, Fusobacterium, Peptostreptococcus, Porphyromonas, Prevotella, Propionibacterium, and Veillonella. Clostridium species are endospore-forming bacteria, and can survive in atmospheric concentrations of oxygen in this dormant form. The remaining bacteria listed do not form endospores.[5]

Examples of obligately anaerobic fungal genera include the rumen fungi Neocallimastix, Piromonas, and Sphaeromonas.[7]

See also

- Aerobic respiration

- Anaerobic respiration

- Fermentation

- Obligate aerobe

- Facultative anaerobe

- Microaerophile

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Prescott LM, Harley JP, Klein DA (1996). Microbiology (3rd ed.). Wm. C. Brown Publishers. pp. 130–131. ISBN 0-697-29390-4.

- 1 2 3 Brooks GF, Carroll KC, Butel JS, Morse SA (2007). Jawetz, Melnick & Adelberg's Medical Microbiology (24th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 307–312. ISBN 0-07-128735-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ryan KJ; Ray CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 309–326, 378–384. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9.

- 1 2 3 4 Hogg, S. (2005). Essential Microbiology (1st ed.). Wiley. pp. 99–100, 118–148. ISBN 0-471-49754-1.

- 1 2 3 4 Levinson, W. (2010). Review of Medical Microbiology and Immunology (11th ed.). McGraw-Hill. pp. 91–178. ISBN 978-0-07-174268-9.

- 1 2 3 4 Kim BH, Gadd GM (2008). Bacterial Physiology and Metabolism.

- ↑ Carlile MJ, Watkinson SC (1994). The Fungi. Academic Press. pp. 33–34. ISBN 0-12-159960-4.