Onion

| Onion | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Order: | Asparagales |

| Family: | Amaryllidaceae |

| Subfamily: | Allioideae |

| Genus: | Allium |

| Species: | A. cepa |

| Binomial name | |

| Allium cepa L. | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

Species synonymy

| |

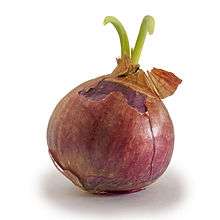

The onion (Allium cepa L., from Latin cepa "onion"), also known as the bulb onion or common onion, is a vegetable and is the most widely cultivated species of the genus Allium.

This genus also contains several other species variously referred to as onions and cultivated for food, such as the Japanese bunching onion (Allium fistulosum), the tree onion (A. ×proliferum), and the Canada onion (Allium canadense). The name "wild onion" is applied to a number of Allium species, but A. cepa is exclusively known from cultivation. Its ancestral wild original form is not known, although escapes from cultivation have become established in some regions.[2] The onion is most frequently a biennial or a perennial plant, but is usually treated as an annual and harvested in its first growing season.

The onion plant has a fan of hollow, bluish-green leaves and its bulb at the base of the plant begins to swell when a certain day-length is reached. In the autumn (or in spring, in the case of overwintering onions), the foliage dies down and the outer layers of the bulb become dry and brittle. The crop is harvested and dried and the onions are ready for use or storage. The crop is prone to attack by a number of pests and diseases, particularly the onion fly, the onion eelworm, and various fungi cause rotting. Some varieties of A. cepa, such as shallots and potato onions, produce multiple bulbs.

Onions are cultivated and used around the world. As a food item, they are usually served cooked, as a vegetable or part of a prepared savoury dish, but can also be eaten raw or used to make pickles or chutneys. They are pungent when chopped and contain certain chemical substances which irritate the eyes.

Taxonomy and etymology

The onion plant (Allium cepa), also known as the bulb onion[3] or common onion,[4] is the most widely cultivated species of the genus Allium.[5][6] It was first officially described by Carl Linnaeus in his 1753 work Species Plantarum.[7] A number of synonyms have appeared in its taxonomic history:

- Allium cepa var. aggregatum – G. Don

- Allium cepa var. bulbiferum – Regel

- Allium cepa var. cepa – Linnaeus

- Allium cepa var. multiplicans – L.H. Bailey

- Allium cepa var. proliferum – (Moench) Regel

- Allium cepa var. solaninum – Alef

- Allium cepa var. viviparum – (Metz) Mansf.[8][9]

A. cepa is known exclusively from cultivation,[10] but related wild species occur in Central Asia. The most closely related species include A. vavilovii (Popov & Vved.) and A. asarense (R.M. Fritsch & Matin) from Iran.[11] However, Zohary and Hopf state that "there are doubts whether the A. vavilovii collections tested represent genuine wild material or only feral derivatives of the crop."[12]

The vast majority of cultivars of A. cepa belong to the "common onion group" (A. cepa var. cepa) and are usually referred to simply as "onions". The Aggregatum group of cultivars (A. cepa var. aggregatum) includes both shallots and potato onions.[13]

The genus Allium also contains a number of other species variously referred to as onions and cultivated for food, such as the Japanese bunching onion (A. fistulosum), Egyptian onion (A. ×proliferum), and Canada onion (A. canadense).[4]

Cepa is commonly accepted as Latin for "onion" and has an affinity with Ancient Greek: κάπια (kápia), Albanian: qepë, Aromanian: tseapã, Catalan: ceba, English: chive, Occitan: ceba, Old French: cive, and Romanian: ceapă.

Description

| Stereo image | ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| Onion seeds have a very distinct shape. |

The onion plant has been grown and selectively bred in cultivation for at least 7,000 years. It is a biennial plant, but is usually grown as an annual. Modern varieties typically grow to a height of 15 to 45 cm (6 to 18 in). The leaves are yellowish- to bluish green and grow alternately in a flattened, fan-shaped swathe. They are fleshy, hollow, and cylindrical, with one flattened side. They are at their broadest about a quarter of the way up, beyond which they taper towards a blunt tip. The base of each leaf is a flattened, usually white sheath that grows out of a basal disc. From the underside of the disc, a bundle of fibrous roots extends for a short way into the soil. As the onion matures, food reserves begin to accumulate in the leaf bases and the bulb of the onion swells.[14]

In the autumn, the leaves die back and the outer scales of the bulb become dry and brittle, so the crop is then normally harvested. If left in the soil over winter, the growing point in the middle of the bulb begins to develop in the spring. New leaves appear and a long, stout, hollow stem expands, topped by a bract protecting a developing inflorescence. The inflorescence takes the form of a globular umbel of white flowers with parts in sixes. The seeds are glossy black and triangular in cross section.[14]

Uses

Historical use

Bulbs from the onion family are thought to have been used as a food source for millennia. In Bronze Age settlements, traces of onion remains were found alongside date stones and fig remains that date back to 5000 BC.[15] However, whether these were cultivated onions is not clear. Archaeological and literary evidence such as the Book of Numbers 11:5 suggests that onions were probably being cultivated around 2000 years later in ancient Egypt, at the same time that leeks and garlic were cultivated. Workers who built the Egyptian pyramids may have been fed radishes and onions.[15]

The onion is easily propagated, transported, and stored. The ancient Egyptians revered the onion bulb, viewing its spherical shape and concentric rings as symbols of eternal life.[16] Onions were even used in Egyptian burials, as evidenced by onion traces being found in the eye sockets of Ramesses IV.[17]

In ancient Greece, athletes ate large quantities of onion because it was believed to lighten the balance of the blood.[16] Roman gladiators were rubbed down with onions to firm up their muscles.[16] In the Middle Ages, onions were such an important food that people paid their rent with onions, and even gave them as gifts.[16] Doctors were known to prescribe onions to facilitate bowel movements and erections, and to relieve headaches, coughs, snakebite, and hair loss.[16]

Onions were taken by the first European settlers to North America, where the Native Americans were already using wild onions in a number of ways, eating them raw or cooked in a variety of foods. They also used them to make into syrups, to form poultices, and in the preparation of dyes. According to diaries kept by the colonists, bulb onions were one of the first things planted by the Pilgrim fathers when they cleared the land for cropping.[16]

Onions were also prescribed by doctors in the early 16th century to help with infertility in women. They were similarly used to raise fertility levels in dogs, cats, and cattle, but this was an error, as recent research has shown that onions are toxic to dogs, cats, guinea pigs, and many other animals.[18][19][20]

Culinary uses

Onions are commonly chopped and used as an ingredient in various hearty warm dishes, and may also be used as a main ingredient in their own right, for example in French onion soup or onion chutney. They are very versatile and can be baked, boiled, braised, grilled, fried, roasted, sautéed, or eaten raw in salads.[21] Their layered nature makes them easy to hollow out once cooked, facilitating stuffing them, as in sogan-dolma. Onions are a staple in Indian cuisine, used as a thickening agent for curries and gravies. Onions pickled in vinegar are eaten as a snack. These are traditionally a side serving in pubs and fish and chip shops throughout the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth. Pickled onions form part of a British pub ploughman's lunch, usually served with cheese and ale. In North America, sliced onions are battered, deep-fried, and served as onion rings.[22]

Onion types and products

Common onions are normally available in three colour varieties. Yellow or brown onions (called red in some European countries), are full-flavoured and are the onions of choice for everyday use. Yellow onions turn a rich, dark brown when caramelized and give French onion soup its sweet flavour. The red onion (called purple in some European countries) is a good choice for fresh use when its colour livens up the dish; it is also used in grilling. White onions are the traditional onions used in classic Mexican cuisine; they have a golden colour when cooked and a particularly sweet flavour when sautéed.[23][24]

While the large, mature onion bulb is most often eaten, onions can be eaten at immature stages. Young plants may be harvested before bulbing occurs and used whole as spring onions or scallions.[25] When an onion is harvested after bulbing has begun, but the onion is not yet mature, the plants are sometimes referred to as "summer" onions.[26]

Additionally, onions may be bred and grown to mature at smaller sizes. Depending on the mature size and the purpose for which the onion is used, these may be referred to as pearl, boiler, or pickler onions, but differ from true pearl onions which are a different species.[26] Pearl and boiler onions may be cooked as a vegetable rather than as an ingredient and pickler onions are often preserved in vinegar as a long-lasting relish.[27]

Onions are available in fresh, frozen, canned, caramelized, pickled, and chopped forms. The dehydrated product is available as kibbled, sliced, ring, minced, chopped, granulated, and powder forms.[28]

Onion powder is a seasoning widely used when the fresh ingredient is not available. It is made from finely ground, dehydrated onions, mainly the pungent varieties of bulb onions, and has a strong odour. Being dehydrated, it has a long shelf life and is available in several varieties: yellow, red, and white.[29]

Non-culinary uses

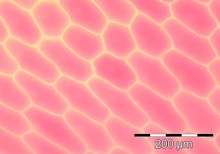

Onions have particularly large cells that are readily observed under low magnification. Forming a single layer of cells, the bulb epidermis is easy to separate for educational, experimental, and breeding purposes.[30][31][32] Onions are, therefore, commonly employed in science education to teach the use of a microscope for observing cell structure.[33]

The pungent juice of onions has been used as a moth repellent and can be rubbed on the skin to prevent insect bites. It has been used to polish glass and copperware and to prevent rust on iron. Onion skins have been used to produce a yellow-brown dye.[34]

Historically, onions were often used for cromniomancy across Europe, Africa, and northern Asia, and they continue to be used for this practice in some rural areas.

Nutrients and phytochemicals

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 166 kJ (40 kcal) |

|

9.34 g | |

| Sugars | 4.24 g |

| Dietary fiber | 1.7 g |

|

0.1 g | |

|

1.1 g | |

| Vitamins | |

| Thiamine (B1) |

(4%) 0.046 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) |

(2%) 0.027 mg |

| Niacin (B3) |

(1%) 0.116 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) |

(2%) 0.123 mg |

| Vitamin B6 |

(9%) 0.12 mg |

| Folate (B9) |

(5%) 19 μg |

| Vitamin C |

(9%) 7.4 mg |

| Minerals | |

| Calcium |

(2%) 23 mg |

| Iron |

(2%) 0.21 mg |

| Magnesium |

(3%) 10 mg |

| Manganese |

(6%) 0.129 mg |

| Phosphorus |

(4%) 29 mg |

| Potassium |

(3%) 146 mg |

| Zinc |

(2%) 0.17 mg |

| Other constituents | |

| Water | 89.11 g |

| Fluoride | 1.1 µg |

|

| |

| |

|

Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

Most onion cultivars are about 89% water, 4% sugar, 1% protein, 2% fibre, and 0.1% fat. Onions contain low amounts of essential nutrients (right table), are low in fats, and have an energy value of 166 kJ (40 kcal) per 100 g (3.5 oz). They contribute their flavor to savory dishes without raising caloric content appreciably.[24]

Onions contain phytochemical compounds such as phenolics that are under basic research to determine their possible properties in humans.[35][36][37][38]

Considerable differences exist between onion varieties in polyphenol content, with shallots having the highest level, six times the amount found in Vidalia onions, the variety with the smallest amount.[35][36] Yellow onions have the highest total flavonoid content, an amount 11 times higher than in white onions.[35] Red onions have considerable content of anthocyanin pigments, with at least 25 different compounds identified representing 10% of total flavonoid content.[36]

Some people suffer from allergic reactions after handling onions.[5] Symptoms can include contact dermatitis, intense itching, rhinoconjunctivitis, blurred vision, bronchial asthma, sweating, and anaphylaxis. Allergic reactions may not occur in these individuals to the consumption of onions, perhaps because of the denaturing of the proteins involved during the cooking process.[39]

While onions and other members of the genus Allium are commonly consumed by humans, they can be deadly for dogs, cats, guinea pigs, monkeys, and other animals.[5][18][19][20] The toxicity is caused by the sulfoxides present in raw and cooked onions, which many animals are unable to digest. Ingestion results in anaemia caused by the distortion and rupture of red blood cells. Sick pets are sometimes fed with tinned baby foods, and any that contain onion should be avoided.[40] The typical toxic doses are 5 g (0.2 oz) per kg (2.2 lb) bodyweight for cats and 15 to 30 g (0.5 to 1.1 oz) per kg for dogs.[18]

Similar to garlic,[41][42][43] onions can show an additional color after cutting.[44] This color is pink-red. It is caused by reactions of the amino acids with the sulfur compounds.

Eye irritation

.jpg)

Freshly cut onions often cause a stinging sensation in the eyes of people nearby, and often uncontrollable tears. This is caused by the release of a volatile gas, syn-propanethial-S-oxide, which stimulates nerves in the eye creating a stinging sensation.[5] This gas is produced by a chain of reactions which serve as a defense mechanism: chopping an onion causes damage to cells which releases enzymes called alliinases. These break down amino acid sulfoxides and generate sulfenic acids. A specific sulfenic acid, 1-propenesulfenic acid, is rapidly acted on by a second enzyme, the lacrimatory factor synthase, producing the syn-propanethial-S-oxide.[5] This gas diffuses through the air and soon reaches the eyes, where it activates sensory neurons. Lacrimal glands produce tears to dilute and flush out the irritant.[45]

Eye irritation can be avoided by cutting onions under running water or submerged in a basin of water.[45] Leaving the root end intact also reduces irritation as the onion base has a higher concentration of sulphur compounds than the rest of the bulb.[46] Refrigerating the onions before use reduces the enzyme reaction rate and using a fan can blow the gas away from the eyes. The more often one chops onions, the less one experiences eye irritation.[47]

The amount of sulfenic acids and lacrimal factor released and the irritation effect differs among Allium species. In 2008, the New Zealand Institute for Crop and Food Research created "no tears" onions by using gene-silencing biotechnology to prevent the synthesis of lachrymatory factor synthase in onions.[48]

Cultivation

Onions are best cultivated in fertile soils that are well-drained. Sandy loams are good as they are low in sulphur, while clayey soils usually have a high sulphur content and produce pungent bulbs. Onions require a high level of nutrients in the soil. Phosphorus is often present in sufficient quantities, but may be applied before planting because of its low level of availability in cold soils. Nitrogen and potash can be applied at regular intervals during the growing season, the last application of nitrogen being at least four weeks before harvesting.[49] Bulbing onions are day-length sensitive; their bulbs begin growing only after the number of daylight hours has surpassed some minimal quantity. Most traditional European onions are referred to as "long-day" onions, producing bulbs only after 14 hours or more of daylight occurs. Southern European and North African varieties are often known as "intermediate-day" types, requiring only 12–13 hours of daylight to stimulate bulb formation. Finally, "short-day" onions, which have been developed in more recent times, are planted in mild-winter areas in the fall and form bulbs in the early spring, and require only 11–12 hours of daylight to stimulate bulb formation.[50] Onions are a cool-weather crop and can be grown in USDA zones 3 to 9.[51] Hot temperatures or other stressful conditions cause them to "bolt", meaning that a flower stem begins to grow.[52]

Onions may be grown from seed or from sets. Onion seeds are short-lived and fresh seeds germinate better.[51][53] The seeds are sown thinly in shallow drills, thinning the plants in stages. In suitable climates, certain cultivars can be sown in late summer and autumn to overwinter in the ground and produce early crops the following year.[14] Onion sets are produced by sowing seed thickly in early summer in poor soil and the small bulbs produced are harvested in the autumn. These bulbs are planted the following spring and grow into mature bulbs later in the year.[54] Certain cultivars are used for this purpose and these may not have such good storage characteristics as those grown directly from seed.[14]

Routine care during the growing season involves keeping the rows free of competing weeds, especially when the plants are young. The plants are shallow-rooted and do not need a great deal of water when established. Bulbing usually takes place after 12 to 18 weeks. The bulbs can be gathered when needed to eat fresh, but if they will be kept in storage, they should be harvested after the leaves have died back naturally. In dry weather, they can be left on the surface of the soil for a few days to dry out properly, then they can be placed in nets, roped into strings, or laid in layers in shallow boxes. They should be stored in a well-ventilated, cool place such as a shed.[14]

Pests and diseases

Onions suffer from a number of plant disorders. The most serious for the home gardener are likely to be the onion fly, stem and bulb eelworm, white rot, and neck rot. Diseases affecting the foliage include rust and smut, downy mildew, and white tip disease. The bulbs may be affected by splitting, white rot, and neck rot. Shanking is a condition in which the central leaves turn yellow and the inner part of the bulb collapses into an unpleasant-smelling slime. Most of these disorders are best treated by removing and burning affected plants.[55] The larvae of the onion leaf miner or leek moth (Acrolepiopsis assectella) sometimes attack the foliage and may burrow down into the bulb. [56]

The onion fly (Delia antiqua) lays eggs on the leaves and stems and on the ground close to onion, shallot, leek, and garlic plants. The fly is attracted to the crop by the smell of damaged tissue and is liable to occur after thinning. Plants grown from sets are less prone to attack. The larvae tunnel into the bulbs and the foliage wilts and turns yellow. The bulbs are disfigured and rot, especially in wet weather. Control measures may include crop rotation, the use of seed dressings, early sowing or planting, and the removal of infested plants.[57]

The onion eelworm (Ditylenchus dipsaci), a tiny parasitic soil-living nematode, causes swollen, distorted foliage. Young plants are killed and older ones produce soft bulbs. No cure is known and affected plants should be uprooted and burned. The site should not be used for growing onions again for several years and should also be avoided for growing carrots, parsnips, and beans, which are also susceptible to the eelworm.[58]

White rot of onions, leeks, and garlic is caused by the soil-borne fungus Sclerotium cepivorum. As the roots rot, the foliage turns yellow and wilts. The bases of the bulbs are attacked and become covered by a fluffy white mass of mycelia, which later produces small, globular black structures called sclerotia. These resting structures remain in the soil to reinfect a future crop. No cure for this fungal disease exists, so affected plants should be removed and destroyed and the ground used for unrelated crops in subsequent years.[59]

Neck rot is a fungal disease affecting onions in storage. It is caused by Botrytis allii, which attacks the neck and upper parts of the bulb, causing a grey mould to develop. The symptoms often first occur where the bulb has been damaged and spread downwards in the affected scales. Large quantities of spores are produced and crust-like sclerotia may also develop. In time, a dry rot sets in and the bulb becomes a dry, mummified structure. This disease may be present throughout the growing period, but only manifests itself when the bulb is in storage. Antifungal seed dressings are available and the disease can be minimised by preventing physical damage to the bulbs at harvesting, careful drying and curing of the mature onions, and correct storage in a cool, dry place with plenty of circulating air.[60]

Storage in the home

Cooking onions and sweet onions are better stored at room temperature, optimally in a single layer, in mesh bags in a dry, cool, dark, well-ventilated location. In this environment, cooking onions have a shelf life of three to four weeks and sweet onions one to two weeks. Cooking onions will absorb odours from apples and pears. Also, they draw moisture from vegetables with which they are stored which may cause them to decay.[51][61]

Sweet onions have a greater water and sugar content than cooking onions. This makes them sweeter and milder tasting, but reduces their shelf life. Sweet onions can be stored refrigerated; they have a shelf life of around 1 month. Irrespective of type, any cut pieces of onion are best tightly wrapped, stored away from other produce, and used within two to three days.[46]

Varieties

Common onion group (var. cepa)

Most of the diversity within A. cepa occurs within this group, the most economically important Allium crop. Plants within this group form large single bulbs, and are grown from seed or seed-grown sets. The majority of cultivars grown for dry bulbs, salad onions, and pickling onions belong to this group.[13] The range of diversity found among these cultivars includes variation in photoperiod (length of day that triggers bulbing), storage life, flavour, and skin colour.[62] Common onions range from the pungent varieties used for dried soups and onion powder to the mild and hearty sweet onions, such as the Vidalia from Georgia, USA, or Walla Walla from Washington that can be sliced and eaten raw on a sandwich.

Aggregatum group (var. aggregatum)

This group contains shallots and potato onions, also referred to as multiplier onions. The bulbs are smaller than those of common onions, and a single plant forms an aggregate cluster of several bulbs. They are propagated almost exclusively from daughter bulbs, although reproduction from seed is possible. Shallots are the most important subgroup within this group and comprise the only cultivars cultivated commercially. They form aggregate clusters of small, narrowly ovoid to pear-shaped bulbs. Potato onions differ from shallots in forming larger bulbs with fewer bulbs per cluster, and having a flattened (onion-like) shape. However, intermediate forms exist.[13]

I'itoi onion is a prolific multiplier onion cultivated in the Baboquivari Peak Wilderness, Arizona area. This small-bulb type has a shallot-like flavor and is easy to grow and ideal for hot, dry climates. Bulbs are separated, and planted in the fall 1 in below the surface and 12 in apart. Bulbs will multiply into clumps and can be harvested throughout the cooler months. Tops die back in the heat of summer and may return with heavy rains; bulbs can remain in the ground or be harvested and stored in a cool dry place for planting in the fall. The plants rarely flower; propagation is by division.[63]

Hybrids with A. cepa parentage

A number of hybrids are cultivated that have A. cepa parentage, such as the diploid tree onion or Egyptian onion (A. ×proliferum), Wakegi onion (A. ×wakegi), and the triploid onion (A. ×cornutum).

The tree onion or Egyptian onion produces bulblets in the umbel instead of flowers, and is now known to be a hybrid of A. cepa × A. fistulosum. It has previously been treated as a variety of A. cepa, for example A. cepa var. proliferum, A. cepa var. bulbiferum, and A. cepa var. viviparum.[64]

The Wakegi onion is also known to be a hybrid between A. cepa and A. fistulosum, with the A. cepa parent believed to be from the Aggregatum group of cultivars.[65] It has been grown for centuries in Japan and China for use as a salad onion.[66]

Under the rules of botanical nomenclature, both the Egyptian onion and Wakegi onion should be combined into one hybrid species, having the same parent species. Where this is followed, the Egyptian onion is named A. ×proliferum Eurasian group and the Wakegi onion is named A. ×proliferum East Asian group.[4]

The triploid onion is a hybrid species with three sets of chromosomes, two sets from A. cepa and the third set from an unknown parent.[65] Various clones of the triploid onion are grown locally in different regions, such as 'Ljutika' in Croatia, and 'Pran', 'Poonch', and 'Srinagar' in the India-Kashmir region. 'Pran' is grown extensively in the northern Indian provinces of Jammu and Kashmir. There are very small genetic differences between 'Pran' and the Croatian clone 'Ljutika', implying a monophyletic origin for this species.[67]

Some authors have used the name A. cepa var. viviparum (Metzg.) Alef. for the triploid onion, but this name has also been applied to the Egyptian onion. The only name unambiguously connected with the triploid onion is A. ×cornutum.

Spring onions or salad onions may be grown from the Welsh onion (A. fistulosum), as well as from A. cepa. Young plants of A. fistulosum and A. cepa look very similar, but may be distinguished by their leaves, which are circular in cross-section in A. fistulosum rather than flattened on one side.[68]

Production and trade

An estimated 9,000,000 acres (3,642,000 ha) of onions are grown around the world, annually. About 170 countries cultivate onions for domestic use and about 8% of the global production is traded internationally.[24]

| Top Ten Onions (dry) Producers — 2012 (metric tons) | |

|---|---|

| | 20,507,759 |

| | 13,372,100 |

| | 3,320,870 |

| | 2,208,080 |

| | 1,922,970 |

| | 1,900,000 |

| | 1,701,100 |

| | 1,556,000 |

| | 1,536,300 |

| | 1,411,650 |

| World Total | 74,250,809 |

| Source: UN Food & Agriculture Organisation (FAO)[69] | |

The Onion Futures Act, passed in 1958, bans the trading of futures contracts on onions in the United States. This prohibition came into force after farmers complained about alleged market manipulation by Sam Seigel and Vincent Kosuga at the Chicago Mercantile Exchange two years earlier. The subsequent investigation provided economists with a unique case study into the effects of futures trading on agricultural prices. The act remains in effect as of 2013.[70]

See also

References

- ↑ "Allium cepa L. — The Plant List". theplantlist.org.

- ↑ "Allium cepa in Flora of North America – v 26". efloras.org. p. 244.

- ↑ Germplasm Resources Information Network – (GRIN). "Allium cepa information from NPGS/GRIN". USDA, ARS, National Genetic Resources Program. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- 1 2 3 Fritsch, R.M.; Friesen, N. (2002). "Chapter 1: Evolution, Domestication, and Taxonomy". In Rabinowitch, H.D.; Currah. L. Allium Crop Science: Recent Advances. Wallingford, UK: CABI Publishing. pp. 9–10. ISBN 0-85199-510-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Eric Block, "Garlic and Other Alliums: The Lore and the Science" (Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry, 2010)

- ↑ Brewster, James L. (1994). Onions and other vegetable Alliums (1st ed.). Wallingford, UK: CAB International. p. 16. ISBN 0-85198-753-2.

- ↑ Linnaeus, Carolus (1753). Species Plantarum (in Latin). 1. Stockholm: Laurentii Salvii. p. 262.

- ↑ "Allium cepa: Garden onion". The PLANTS Database. USDA: NRCS. 2013. Retrieved 2013-03-31.

- ↑ "Allium cepa L.". ITIS. 2013-03-08. Retrieved 2013-04-01.

- ↑ "Allium cepa Linnaeus". Flora of North America.

- ↑ Grubben, G.J.H.; Denton, O.A. (2004) Plant Resources of Tropical Africa 2. Vegetables. PROTA Foundation, Wageningen; Backhuys, Leiden; CTA, Wageningen.

- ↑ Zohary, Daniel; Hopf, Maria (2000). Domestication of plants in the Old World (Third ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 198. ISBN 0-19-850357-1.

- 1 2 3 Fritsch, R.M.; N. Friesen (2002). "Chapter 1: Evolution, Domestication, and Taxonomy". In H.D. Rabinowitch; L. Currah. Allium Crop Science: Recent Advances. Wallingford, UK: CABI Publishing. pp. 20–21. ISBN 0-85199-510-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Brickell, Christopher (ed) (1992). The Royal Horticultural Society Encyclopedia of Gardening. Dorling Kindersley. p. 345. ISBN 978-0-86318-979-1.

- 1 2 "Onions: Allium cepa". selfsufficientish.com. Retrieved 2006-04-02.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "About Onions: History". Retrieved 2013-09-13.

- ↑ Abdel-Maksouda, Gomaa; El-Aminb, Abdel-Rahman (2011). "A review on the materials used during the mummification process in ancient Egypt" (PDF). Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry. 11 (2): 129–150.

- 1 2 3 Cope, R.B. (August 2005). "Allium species poisoning in dogs and cats" (PDF). Veterinary Medicine. 100 (8): 562–566. ISSN 8750-7943.

- 1 2 Salgado, B.S.; Monteiro, L.N.; Rocha, N.S. (2011). "Allium species poisoning in dogs and cats". Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins Including Tropical Diseases. 17 (1): 4–11. doi:10.1590/S1678-91992011000100002. ISSN 1678-9199.

- 1 2 Yin, Sophia. "Onions: the secret killer?". Retrieved 2011-05-04.

- ↑ Conant, Patricia (2006). "Onion – Culinary Foundation and Medicine". The Epicurean Table. Retrieved 2013-04-02.

- ↑ "Onion". GoodFood. BBC. Retrieved 2013-04-02.

- ↑ Mower, Chris. "The Difference between Yellow, White, and Red Onions". The Cooking Dish. Retrieved 2013-03-24.

- 1 2 3 "All about onions". National Onion Association. Retrieved 2013-03-24.

- ↑ Thompson, Sylvia (1995). "The Kitchen Garden". Bantam Books: 142.

- 1 2 Thompson, Sylvia (1995). "The Kitchen Garden". Bantam Books: 143.

- ↑ Ministry of Agriculture; Fisheries and Food (1968). Home Preservation of Fruit and Vegetables. HMSO. p. 107.

- ↑ "Onion and Onion Products". NIIR Project Consultancy Services. Retrieved 2013-03-31.

- ↑ Smith, S. E. (2013). "What is onion powder". WiseGeek. Conjecture Corporation. Retrieved 2013-04-02.

- ↑ Suslov, D; Verbelen, J. P.; Vissenberg, K (2009). "Onion epidermis as a new model to study the control of growth anisotropy in higher plants". Journal of Experimental Botany. 60 (14): 4175–87. doi:10.1093/jxb/erp251. PMID 19684107.

- ↑ Xu, K; Huang, X; Wu, M; Wang, Y; Chang, Y; Liu, K; Zhang, J; Zhang, Y; Zhang, F; Yi, L; Li, T; Wang, R; Tan, G; Li, C (2014). "A rapid, highly efficient and economical method of Agrobacterium-mediated in planta transient transformation in living onion epidermis". PLoS ONE. 9 (1): e83556. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0083556. PMC 3885512

. PMID 24416168.

. PMID 24416168. - ↑ "Genetics Teaching Vignettes: Elementary School". 2004-06-15. Archived from the original on 2013-08-28.

- ↑ Anne McCabe; Mick O'Donnell; Rachel Whittaker (19 July 2007). Advances in Language and Education. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-4411-0458-8.

- ↑ "United States Patent Office: Method of coloring eggs or the like". 1925-06-19. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

- 1 2 3 Yang, J.; Meyers, K. J.; Van Der Heide, J.; Liu, R. H. (2004). "Varietal Differences in Phenolic Content and Antioxidant and Antiproliferative Activities of Onions". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 52 (22): 6787–6793. doi:10.1021/jf0307144. PMID 15506817.

- 1 2 3 Slimestad, R; Fossen, T; Vågen, I. M. (2007). "Onions: A source of unique dietary flavonoids". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 55 (25): 10067–80. doi:10.1021/jf0712503. PMID 17997520.

- ↑ Williamson, Gary; Plumb, Geoff W.; Uda, Yasushi; Price, Keith R.; Rhodes, Michael J.C. (1997). "Dietary quercetin glycosides: antioxidant activity and induction of the anticarcinogenic phase II marker enzyme quinone reductase in Hepalclc7 cells". Carcinogenesis. 17 (11): 2385–2387. doi:10.1093/carcin/17.11.2385. PMID 8968052.

- ↑ Olsson, M.E.; Gustavsson, K.E. & Vågen, I.M. (2010). "Quercetin and isorhamnetin in sweet and red cultivars of onion (Allium cepa L.) at harvest, after field curing, heat treatment, and storage". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 58 (4): 2323–2330. doi:10.1021/jf9027014. PMID 20099844.

- ↑ Arochena, L.; Gámez, C.; del Pozo, V.; Fernández-Nieto, M. (2012). "Cutaneous allergy at the supermarket". Journal of Investigational Allergology and Clinical Immunology. 22 (6): 441–442. PMID 23101191.

- ↑ Wissman, Margaret A. (1994). "Anemia caused by onions". Anemia in primates. Retrieved 2013-04-01.

- ↑ Cho, Jungeun; Lee, Eun Jin; Yoo, Kil Sun; Lee, Seung Koo; Patil, Bhimanagouda S. (2009-01-01). "Identification of Candidate Amino Acids Involved in the Formation of Blue Pigments in Crushed Garlic Cloves (Allium sativum L.)". Journal of Food Science. 74 (1): C11–C16. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3841.2008.00986.x. ISSN 1750-3841.

- ↑ Lukes, T. M. (1986-11-01). "Factors Governing the Greening of Garlic Puree". Journal of Food Science. 51 (6): 1577–1577. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1986.tb13869.x. ISSN 1750-3841.

- ↑ Sano, T. (1950). Green pigment formation in ground garlic. M.S. thesis: Unv. of California, Berkeley.

- ↑ Lee, Eun Jin; Rezenom, Yohannes H.; Russell, David H.; Patil, Bhimanagouda S.; Yoo, Kil Sun (2012-04-01). "Elucidation of chemical structures of pink-red pigments responsible for 'pinking' in macerated onion (Allium cepa L.) using HPLC–DAD and tandem mass spectrometry". Food Chemistry. 131 (3): 852–861. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.09.059.

- 1 2 Scott, Thomas. "What is the chemical process that causes my eyes to tear when I peel an onion?". Ask the Experts: Chemistry. Scientific American. Retrieved 2007-04-28.

- 1 2 "FAQ". National Onion Association. Retrieved 2013-03-28.

- ↑ Hiskey, Daven (2010-11-05). "Why onions make your eyes water". Today I Found Out. Retrieved 2013-03-28.

- ↑ "Tearless Onion Created In Lab Using Gene Silencing". ScienceDaily. 5 February 2008. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ↑ Boyhan, George E.; Kelley, W. Terry (eds.) (2007). "2007 Onion Production Guide". Production Guides. University of Georgia: College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences. Retrieved 2013-09-14.

- ↑ Savonen, Carol (2006-07-13). "Onion bulb formation is strongly linked with day length". Oregon State University Extension Service. Retrieved 2013-09-14.

- 1 2 3 "Onions: Planting, Growing and Harvesting Onion Plants". The Old Farmer's Almanac. Retrieved 2013-03-27.

- ↑ Rhoades, Jackie. "What is Onion Bolting and how to Keep an Onion from Bolting". Gardening Know How. Retrieved 2013-03-27.

- ↑ "Onion production". USDA: Agricultural Research Service. 2011-02-23. Retrieved 2013-03-27.

- ↑ Fern, Ken; Fern, Addy. "Allium cepa – L.". Plants For A Future. Retrieved 2013-03-22.

- ↑ Hessayon, D.G. (1978). Be your own Vegetable Doctor. Pan Britannica Industries. pp. 22–23. ISBN 0-903505-08-8.

- ↑ Landry, Jean-François (2007). "Taxonomic review of the leek moth genus Acrolepiopsis (Lepidoptera: Acrolepiidae) in North America". The Canadian Entomologist. 139 (3): 319–353. doi:10.4039/n06-098.

- ↑ "Delia antiqua (Meigen): Onion Fly". Interactive Agricultural Ecological Atlas of Russia and Neighboring Countries. Retrieved 2013-03-29.

- ↑ "Onion Eelworm (Ditylenchus dipsaci)". GardenAction. 2011. Retrieved 2013-03-29.

- ↑ "Onion white rot". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 2013-03-29.

- ↑ "Onion neck rot". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 2013-03-29.

- ↑ Jauron, Richard (2009-07-27). "Harvesting and storing onions". Iowa State University Extension. Retrieved 2013-03-28.

- ↑ Brewster, James L. (1994). Onions and other vegetable Alliums (1st ed.). Wallingford, UK: CAB International. p. 5. ISBN 0-85198-753-2.

- ↑ "I'Itoi Onion". Ark of Taste. Slow Food USA. 2010. Retrieved 2013-03-25.

- ↑ Germplasm Resources Information Network – (GRIN). "Allium x proliferum information from NPGS/GRIN". USDA, ARS, National Genetic Resources Program. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- 1 2 Fritsch, R.M.; N. Friesen (2002). "Chapter 1: Evolution, Domestication, and Taxonomy". In H.D. Rabinowitch; L. Currah. Allium Crop Science: Recent Advances. Wallingford, UK: CABI Publishing. p. 19. ISBN 0-85199-510-1.

- ↑ Brewster, James L. (1994). Onions and other vegetable Alliums (1st ed.). Wallingford, UK: CAB International. p. 15. ISBN 0-85198-753-2.

- ↑ Friesen, N. & M. Klaas (1998). "Origin of some vegetatively propagated Allium crops studied with RAPD and GISH". Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 45 (6): 511–523. doi:10.1023/A:1008647700251.

- ↑ Brewster, James L. (1994). Onions and other vegetable alliums (1st ed.). Wallingford, UK: CAB International. p. 3. ISBN 0-85198-753-2.

- ↑ "Major Food And Agricultural Commodities And Producers – Countries By Commodity". Fao.org. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- ↑ "7 USC § 13–1 – Violations, prohibition against dealings in motion picture box office receipts or onion futures; punishment". United States Code: 7 USC § 13–1. Legal Information Institute. 1958. Retrieved 2013-03-24.

Further reading

- Block, E. (2010). Garlic and Other Alliums: The Lore and the Science. Royal Society of Chemistry (UK). ISBN 978-0-85404-190-9.

- Gripshover, Margaret M., and Thomas L. Bell, "Patently Good Ideas: Innovations and Inventions in U.S. Onion Farming, 1883–1939," Material Culture (Spring 2012), vol 44 pp 1–30.

- Sen, Colleen T. (2004). Food culture in India. Greenwood Publishing. ISBN 0-313-32487-5.

External links

| Look up onion in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikibooks Cookbook has a recipe/module on |

Media related to Onions at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Onions at Wikimedia Commons- PROTAbase on Allium cepa

.jpg)