Operation Savannah (Angola)

| Operation Savannah | |

|---|---|

| Part of the South African Border War | |

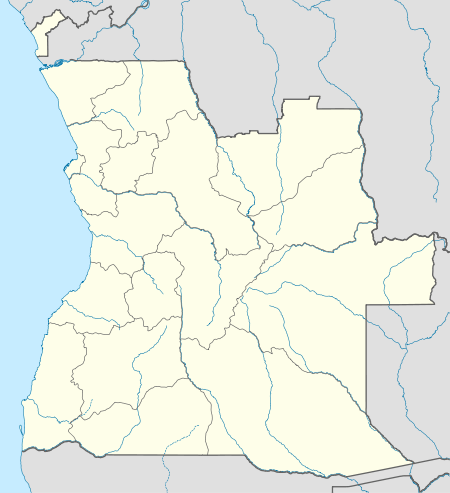

| Location | Angola Cassinga Luanda Ebo Calueque Benguela Ambrizete Lobito Xangongo Huambo Lubango Operation Savannah (Angola) (Angola) |

| Objective | |

| Date | 1975-1976 |

Operation Savannah was the South African Defence Force's 1975–1976 covert intervention in the Angolan War of Independence, and the subsequent Angolan Civil War.

Background

The so-called "Carnation Revolution" of 25 April 1974 ended Portugal's colonial government, but Angola's three main independence forces, National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA), National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA) and the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) began competing for dominance in the country. Fighting began in November 1974, starting in the capital city, Luanda, and spreading quickly across all of Angola, which was soon divided among the combatants. The FNLA occupied northern Angola and UNITA the central south, while the MPLA mostly occupied the coastline, the far south-east and, after capturing it in November 1974, Cabinda. Negotiations for independence resulted in the Treaty of Alvor being signed on 15 January 1975, naming the date of official independence as 11 November 1975. The agreement ended the war for independence but marked the escalation of the civil war. Two dissenting groups, the Front for the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda and the Eastern Revolt, never signed the accords, as they were excluded from negotiations. The coalition government established by the Treaty of Alvor soon ended as nationalist factions, doubting one another's intentions, tried to control the country by force. [1][2] Fighting between the three forces resumed in Luanda hardly a day after the transitional government assumed office on 15 January 1975.[3][4][5][6]

The liberation forces sought to seize strategic points, most importantly the capital, by the official day of independence. The MPLA managed to seize Luanda from the FLNA whilst UNITA retreated from the capital. By March 1975, the FNLA was driving towards Luanda from the north, joined by units of the Zairian army which the United States had encouraged Zaire to provide.[7] Between 28 April and early May, 1,200 Zairian troops crossed into northern Angola to assist the FNLA. [8] [9] The FNLA eliminated all remaining MPLA presence in the northern provinces and assumed positions east of Kifangondo on the eastern outskirts of Luanda, from where it continued to encroach on the capital.[10][11] The situation for the MPLA in Luanda became increasingly precarious.[6]

The MPLA received supplies from the Soviet Union and repeatedly requested 100 officers for military training from Cuba. Until late August, Cuba had a few technical advisors deployed in Angola.[12] By 9 July, the MPLA gained control of the capital, Luanda.

Starting 21 August, Cuba established four training facilities (CIR) with almost 500 men, which were to train about 4,800 FAPLA recruits in three to six months.[13][14] The mission was expected to be short-term and to last about 6 months.[15] The CIR in Cabinda accounted for 191 instructors, while Benguela, Saurimo (formerly Henrique de Carvalho) and at N'Dalatando (formerly Salazar) had 66 or 67 instructors each. Some were posted in headquarters in Luanda or in other places throughout the country. The training centres were operational by 18–20 October.[16]

Military intervention

South African Defence Force (SADF) involvement in Angola, part of the interrelated South African Border War, started in 1966 when the South West African People's Organization (SWAPO) commenced an armed struggle for Namibian independence. SWAPO officials founded an armed wing, the People's Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN), which operated from bases in Zambia and rural Ovamboland.[6][17]

With the loss of the Portuguese colonial administration as an ally and the possibility of new regimes sympathetic to SWAPO in Lisbon's former colonies, Pretoria recognised that it would lose a valued cordon sanitaire between South West Africa and the Frontline States.[17][18][19][20] PLAN could seek sanctuary in Angola, and South Africa would be faced with another hostile regime and potentially militarised border to cross in pursuit of Namibian guerrillas.

With both the Soviet Union and the United States arming major factions in the Angolan Civil War, the conflict escalated into a major Cold War battleground. South Africa offered advisory and technical assistance to UNITA, while a number of Cuban combat troops entered the country to fight alongside the Marxist MPLA. Moscow also plied its Angolan clients with heavy weapons. American aid to UNITA and the FNLA was initially undertaken with Operation IA Feature, but this was terminated by the Clark Amendment in October 1976. Aid would not yet return until after the repeal of the Clark Amendment in 1985.[21] China subsequently recalled its military advisers from Zaire, ending its tacit support for the FNLA.[22]

Cuban instructors began training PLAN in Zambia in April 1975, and the movement had 3,000 new recruits by April. Guerrilla activity intensified, election boycotts were staged in Ovamboland, and the Ovambo Chief Minister assassinated. South Africa responded by calling up more reservists and placing existing security forces along the border on standby. Raids into Angola became commonplace after July 15.[23]

Support for UNITA and FNLA

Consequently, with the covert assistance of the United States through the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), it began assisting UNITA and the FNLA in a bid to ensure that a neutral or friendly government in Luanda prevailed.[6] On 14 July 1975, South African Prime Minister Balthazar Vorster approved weapons worth US $14 million to be bought secretly for FNLA and UNITA.[24][25] of which the first shipments from South Africa arrived in August 1975.

Ruacana-Calueque occupation

On 9 August 1975 a 30-man SADF patrol moved some 50 kilometres (31 mi) into southern Angola and occupied the Ruacana-Calueque hydro-electric complex and other installations on the Cunene River.[6][26]:39 The scheme was an important strategic asset for Ovamboland, which relied on it for its water supply. The facility had been completed earlier in the year with South African funding.[27] Several hostile incidences with UNITA and SWAPO frightening foreign workers had provided a rationale for the occupation.[28] The defence of the facility in southern Angola also was South Africa's justification for the first permanent deployment of regular SADF units inside Angola.[29][30] On 22 August 1975 the SADF initiated operation "Sausage II", a major raid against SWAPO in southern Angola and on 4 September 1975, Vorster authorized the provision of limited military training, advice and logistical assistance. In turn FNLA and UNITA would help the South Africans fight SWAPO.[17][31]

Meanwhile, the MPLA had gained against UNITA in Southern Angola and by mid-October was in control of 12 of Angola's provinces and most cities. UNITA's territory had been shrinking to parts of central Angola,[32] and it became apparent that UNITA did not have any chance of capturing Luanda by independence day, which neither the United States nor South Africa were willing to accept.[33]

The SADF established a training camp near Silva Porto (Kuito) and prepared the defences of Nova Lisboa (Huambo). They assembled the mobile attack unit "Foxbat" to stop approaching FAPLA-units with which it clashed on 5 October, thus saving Nova Lisboa for UNITA.[6][34]

Task Force Zulu

On 14 October, the South Africans secretly initiated Operation Savannah when Task Force Zulu, the first of several South African columns, crossed from Namibia into Cuando Cubango. The operation provided for elimination of the MPLA from the southern border area, then from south western Angola, from the central region, and finally for the capture of Luanda.[35] According to John Stockwell, a former CIA officer, "there was close liaison between the CIA and the South Africans" [33] and "’high officials’ in Pretoria claimed that their intervention in Angola had been based on an ‘understanding’ with the United States".[36] The intervention was also backed by Zaire and Zambia.[37]

With the liberation forces busy fighting each other, the SADF advanced very quickly. Task Force Foxbat joined the invasion in mid-October.[17][38][39] The territory the MPLA had just gained in the south was quickly lost to the South African advances. After South African advisors and antitank weapons helped to stop an MPLA advance on Nova Lisboa (Huambo) in early October, Zulu captured Rocadas (Xangongo) by 20, Sa da Bandeira (Lubango) by 24 and Mocamedes by 28 October.

With the South Africans moving quickly toward Luanda, the Cubans had to terminate the CIR at Salazar only 3 days after it started operating and deployed most of the instructors and Angolan recruits in Luanda.[40] On 2–3 November, 51 Cubans from the CIR Benguela and South Africans had their first direct encounter near Catengue, where FAPLA unsuccessfully tried to stop the Zulu advance. This encounter led Zulu-Commander Breytenbach to conclude that his troops had faced the best organized FAPLA opposition to date.[41]

For the duration of the campaign, Zulu had advanced 3,159 km in thirty-three days and had fought twenty-one battles / skirmishes in addition to sixteen hasty and fourteen deliberate attacks. the Task Force accounted for an estimated 210 MPLA dead, 96 wounded and 50 POWs while it had suffered 5 dead and 41 wounded.[6][42]

Cuban intervention

After the MPLA debacle at Catengue, the Cubans became very aware of the South African intervention. On 4 November Castro decided to begin an intervention on an unprecedented scale: "Operation Carlota". The same day, a first airplane with 100 heavy weapon specialists, which the MPLA had requested in September, left for Brazzaville, arriving in Luanda on 7 November. On November 9 the first 100 men of a contingent of a 652-strong battalion of elite Special Forces were flown in.[43] The 100 specialists and 88 men of the special forces were dispatched immediately to the nearby front at Kifangondo. They assisted 850 FAPLA, 200 Katangans and one Soviet advisor.

With the help of the Cubans and the Soviet advisor, FAPLA decisively repelled an FNLA-Zairian assault in the Battle of Kifangondo on 8 November.[44] The South African contingent, 52 men commanded by General Ben de Wet Roos, that had provided for the artillery on the northern front, had to be evacuated by ship on 28 November.[45] MPLA-leader Agostinho Neto proclaimed independence and the formation of the People's Republic of Angola on 11 November and became its first President.

South African reinforcements

On 6 and 7 November 1975 Zulu captured the harbour cities of Benguela (terminal of the Benguela railroad) and Lobito. The towns and cities captured by the SADF were given to UNITA. In central Angola, at the same time, combat unit Foxbat had moved 800 kilometres (500 mi) north toward Luanda.[29] By then, the South Africans realised that Luanda could not be captured by independence day on 11 November and the South Africans considered ending the advance and retreating. But on 10 November 1975 Vorster relented to UNITA's urgent request to maintain the military pressure with the objective of capturing as much territory as possible before the impending meeting of the Organization of African Unity.[46] Thus, Zulu and Foxbat continued north with two new battle groups formed further inland (X-Ray and Orange) and "there was little reason to think the FAPLA would be able to stop this expanded force from capturing Luanda within a week." [47] Through November and December 1975, the SADF presence in Angola numbered 2,900 to 3,000 personnel.[6][48]

After Luanda was secured against the north and with reinforcements from Cuba arriving, Zulu faced stronger resistance advancing on Novo Redondo (Sumbe). First Cuban reinforcements arrived in Porto Amboim, only a few km north of Novo Redondo, quickly destroying three bridges crossing the Queve river, effectively stopping the South African advance along the coast on 13 November 1975.[49] Despite concerted efforts to advance north to Novo Redondo, the SADF was unable to break through FAPLA defences.[50][51][52] In a last successful advance a South African task force and UNITA troops captured Luso on the Benguela railway on 11 December which they held until 27 December.[6][53]

End of South African advance

By mid-December South Africa extended military service and brought in reserves.[54][55] "An indication of the seriousness of the situation ... is that one of the most extensive military call-ups in South African history is now taking place".[56] By late December, the Cubans had deployed 3,500 to 4,000 troops in Angola, of which 1,000 were securing Cabinda,[57] and eventually the struggle began to favour of the MPLA.[58] Apart from being "bogged down" on the southern front,[59] the South African advance halted, “as all attempts by Battle-Groups Orange and X-Ray to extend the war into the interior had been forced to turn back by destroyed bridges”.[60] In addition, South Africa had to deal with two other major setbacks: the international press criticism of the operation and the associated change of US policies. Following the discovery of SADF troops in Angola, most African and Western backers declined to continue to back the South Africans due to the negative publicity of links with the Apartheid government.[61] The South African leadership felt betrayed with a member of congress saying “When the chips were down there was not a single state prepared to stand with South Africa. Where was America? Where were Zaire, Zambia ... and South Africa's other friends?"[62]

Major battles and incidents

Battle of Quifangondo

On 10 November 1975, the day before Angolan independence, the FNLA attempted against advice to capture Luanda from the MPLA. South African gunners and aircraft assisted the offensive which went horribly wrong for the attackers; they were routed by the FAPLA assisted by Cubans manning superior weaponry that had arrived recently in the country. The South African artillery, antiquated due to the UN embargo, was not any match for the longer-ranged Cuban BM-21 rocket launchers, and therefore could not influence the result of the battle.

Battle of Ebo

The Cuban military, anticipating a South African advance (under the direction of Lieutenant Christopher du Raan) towards the town of Ebo, established positions there at a river crossing to thwart any assault. The defending artillery force, equipped with a BM-21 battery, a 76mm field gun, and several anti-tank units, subsequently destroyed five to six armoured cars, whilst they were bogged down with RPG-7s, on November 25, killing 5 and wounding 11 South African soldiers. A Cessna spotter aircraft was shot down over Ebo the following day. This was the first tangible South African defeat of Operation Savannah.

"Bridge 14"

Following the ambush at Ebo, the South African Battle Group Foxbat began attempting to breach the Nhia River at "Bridge 14", a strategic crossing near the FAPLA headquarters north of Quibala. This ensuing Battle for Bridge 14 accounted for the many fierce actions fought by withdrawing Cuban and Angolan forces from the river inland to "Top Hat", a hill overlooking the southern approach to the bridge.[6][26]:54[63] In early December, Foxbat had infiltrated the hill with two artillery observers, who directed fire on FAPLA positions from a battery of BL 5.5-inch Medium Guns.[64] This development forced Cuban commander Raúl Arguelles to call off an intended counter-offensive and order a redeployment via Ebo, instructing his units to withdraw from the Nhia. His subsequent death in a landmine explosion caused much confusion in some sectors of the defence line, with several of the defending units overlooking Bridge 14 as a result of a series of miscommunications. Meanwhile, South African sappers started repairing the bridge on December 11 despite heavy FAPLA opposition. By morning the Cuban situation had worsened with Foxbat advancing in full force.[65] At about 7 AM, the defending troops came under attack. Heavy artillery pounded the northern banks, wiping out several mortar positions and at least one ammunition truck. The Cubans, supported by ZPU-4s and BM-21 Grads, covered the main road with Sagger wire-guided missiles to deter the South African advance. However, a column of twelve Eland-90 armoured cars supported by infantry broke through, skirting the road to confuse the missile teams, who had trained their weapons on the centre of the bridge.[66]

The Elands swiftly engaged the remaining mortars with high-explosive shells, routing their crews. Twenty Cuban advisers were also dispatched when they attempted to overtake a Lieutenant van Vuuren's armoured car in the chaos, possibly mistaking it for an Angolan vehicle. Slowing to let the truck pass, van Vuuren promptly slammed a 90mm round into its rear – killing the occupants.[66]

It was during this engagement that Danny Roxo single-handedly killed twelve FAPLA soldiers while conducting a reconnaissance of the bridge, an action for which he was awarded the Honoris Crux.[67] A number of other South African military personnel were also decorated for bravery at Bridge 14, some posthumously. It is estimated that several hundred Cubans lost their lives during the attack; the SADF suffered 4 dead.[6][63][65]

The events at Bridge 14 were subsequently dramatised by South Africa in the 1976 Afrikaans film Brug 14.

Battle of Luso

On December 10, the South African Task Force X-Ray followed the Benguela railway line from Silva Porto (Kuito) east to Luso, which they overran on the 10th December 1975.[68] The South African contingent included an armoured squadron, supporting infantry units, some artillery, engineers, and UNITA irregulars. Their main objective was to seize the Luso airport,[69] which later went on to serve as a supply point until the South Africans finally departed Angola in early January 1976.

Battles involving Battlegroup Zulu in the west

There were numerous unrecorded clashes fought in the southwest between Colonel Jan Breytenbach's SADF battlegroup and scattered MPLA positions during Operation Savannah. Eventually, Breytenbach's men were able to advance three thousand kilometers over Angolan soil in thirty-three days.

On a related note, Battlegroup Zulu later formed the basis of South Africa's famous 32 Battalion.

Ambrizete incident

The South African Navy was not planned to be involved in the hereunto land operation, but after a failed intervention by the South African Army in the Battle of Quifangondo, nevertheless had to hastily extract a number of army personnel by sea from far behind enemy lines in Angola, as well as abandoned guns. Ambrizete north of Luanda at 7°13′25″S 12°51′24″E / 7.22361°S 12.85667°E was chosen as the pick-up point for the gunners involved in the defeat at Quifangondo. The frigates SAS President Kruger and SAS President Steyn went to the area, where the latter used inflatable boats and its Westland Wasp helicopter to extract 26 personnel successfully from the beach on 28 November 1975.[6][70][71] The replenishment oiler SAS Tafelberg provided logistical support to the frigates, and picked up the guns in Ambriz after they were towed to Zaire, and took them to Walvis Bay.

General Constand Viljoen, who had grave concerns at the time about the safety of both his soldiers and abandoned field guns, called it "the most difficult night ever in my operational career".[72]

The success of this operation was exceptionally fortuitous, given that the South African Navy had been penetrated by the spy Dieter Gerhardt.

Aftermath

South Africa continued to assist UNITA in order to ensure that SWAPO did not establish any bases in southern Angola.[6]

The South African Defence Force acknowledged 28 dead and 100 wounded during Operation Savannah.[73]

South African order of battle

The South Africans deployed a number of Combat Groups during Operation Savannah – initially, only Combat Groups A and B were deployed, with the remaining groups being mobilised and deployed into Angola later in the campaign. There has been much dispute the overall size of Task Force Zulu. Current evidence indicates that the Task Force started with approximately 500 men and grew to a total of 2,900 with the formation of Battle Groups Foxbat, Orange and X-Ray.[74]

Association

The Savannah Association is an association of ex-servicemen of all units who were involved in the operation. They meet annually to commemorate the operation. The insignia of the association is a Caltrop.

References

- ↑ Tvedten, Inge (1997). Angola: Struggle for Peace and Reconstruction. p. 36.

- ↑ Schneidman, Witney Wright (2004). Engaging Africa: Washington and the Fall of Portugal's Colonial Empire. p. 200.

- ↑ George, Edward (2005). The Cuban intervention in Angola: 1965–1991. London: Frank Cass. pp. 50–59. ISBN 0415350158.

- ↑ Library of Congress Country Studies: http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?frd/cstdy:@field(DOCID+ao0044)

- ↑ Gleijeses, Piero: Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959–1976, The University of North Carolina Press, 2002

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Steenkamp, Willem (1 March 2006). Borderstrike! South Africa into Angola. 1975–1980 (3rd ed.). Durban, South Africa: Just Done Productions Publishing. ISBN 978-1-920169-00-8. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ↑ Norton, W.: In Search of Enemies: A CIA Story, New York, 1978, quoted in: Smith, Wayne: A Trap in Angola in: Foreign Policy No. 62, Spring 1986, p. 67, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- ↑ Wright, George in: The Destruction of a Nation: United States’ Policy toward Angola since 1945, Pluto Press, London, Chicago, 1997, ISBN 0-7453-1029-X, p. 60

- ↑ George (2005), p. 63

- ↑ Library of Congress Country Studies: http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?frd/cstdy:@field(DOCID+ao0046)

- ↑ Smith, Wayne: A Trap in Angola in: Foreign Policy No. 62, Spring 1986, p. 68 and 70, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- ↑ CIA, National Intelligence Daily, October 11, 1975, p. 4, NSA

- ↑ CIA, National Intelligence Daily, October 11, 1975, p. 4

- ↑ Gleijeses, Piero: Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959–1976 (The University of North Carolina Press) p. 228

- ↑ George (2005), p. 65

- ↑ George (2005), p. 67

- 1 2 3 4 Library of Congress Country Studies: http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?frd/cstdy:@field(DOCID+ao0047)

- ↑ Stührenberg, Michael in: Die Zeit 17/1988, Die Schlacht am Ende der Welt, p. 11

- ↑ Gleijeses, Piero: Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959–1976 (The University of North Carolina Press) p. 273-276

- ↑ Dr. Leopold Scholtz: The Namibian Border War (Stellenbosch University)

- ↑ "Trade Registers". Armstrade.sipri.org. Retrieved 2014-05-11.

- ↑ Hanhimaki, Jussi M. (2004). The Flawed Architect: Henry Kissinger and American Foreign Policy. p. 416.

- ↑ Modern African Wars (3) : South-West Africa (Men-At-Arms Series, 242) by Helmoed-Römer Heitman (Author), Paul Hannon (Illustrator) Osprey Publishing (28 November 1991) ISBN 1-85532-122-X and ISBN 978-1-85532-122-9

- ↑ Gleijeses, Piero: Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959–1976 (The University of North Carolina Press) quoting: Spies, F. J. du Toit in: Operasie Savannah. Angola 1975–1976, Pretoria, p. 64-65

- ↑ Gleijeses, Piero: Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959–1976 (The University of North Carolina Press) quoting: Deon Geldenhuys in: The Diplomacy of Isolation: South African Foreign Policy Making, p. 80

- 1 2 Steenkamp, Willem (1989). South Africa's Border War 1966 – 1989. Ashanti Publishing.

- ↑ "Agreement between the government of the Republic of South Africa and the government of Portugal in regard to the first phase of development of the water resources of the Cunene river basin" (Press release). Département de l'administration et des finances (Portugal). 21 January 1969.

- ↑ Hamann, Hilton (2001). Days of the Generals. New Holland Publishers. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-86872-340-9. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- 1 2 IPRI—Instituto Português de Relações Internacionais : The United States and the Portuguese Decolonization (1974–1976) Kenneth Maxwell, Council on Foreign Relations. Paper presented at the International Conference "Portugal, Europe and the United States", Lisbon, October, 2003

- ↑ Smith, Wayne: A Trap in Angola in: Foreign Policy No. 62, Spring 1986, p. 71, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- ↑ George (2005), p. 68

- ↑ Gleijeses, Piero: Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959–1976 (The University of North Carolina Press) quoting: Bureau of Intelligence and Research, DOS, in: Angola: The MPLA Prepares for Independence, September 22, 1975, p 4-5, National Security Archive, Washington, quoting: Le Monde, September 13, 1975, p. 3 and quoting: Diaz Arguelles to Colomé, October 1, 1975, p. 11

- 1 2 Smith, Wayne: A Trap in Angola in: Foreign Policy No. 62, Spring 1986, p. 72, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- ↑ George (2005), p. 69

- ↑ Gleijeses, Piero: Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959–1976 (The University of North Carolina Press) quoting: Deon Geldenhuys in: The Diplomacy of Isolation: South African Foreign Policy Making, p. 80, quoting: du Preez, Sophia in: Avontuur in Angola. Die verhaal van Suid-Afrika se soldate in Angola 1975–1976, Pretoria, pp. 32, 63, 86 and quoting: Spies, F. J. du Toit in: Operasie Savannah. Angola 1975–1976, Pretoria, pp. 93–101

- ↑ Marcum, John in: Lessons of Angola, Foreign Affairs 54, No. 3 (April 1976), quoted in: Smith, Wayne: A Trap in Angola in: Foreign Policy No. 62, Spring 1986, p. 62, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- ↑ Hamman, H. (2008). Days of the Generals. Cape Town, South Africa: Zebra Press. p. 17.

- ↑ Gleijeses, Piero: Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959–1976 (The University of North Carolina Press) p. 298

- ↑ Smith, Wayne: A Trap in Angola in: Foreign Policy No. 62, Spring 1986, p. 62, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- ↑ George (2005), pp. 73–74

- ↑ George (2005), p. 76

- ↑ Eriksen, Garrett Ernst (2000). Fighting Columns In Small Wars: An OMFTS Model. p. 16.

- ↑ George (2005), pp. 77–78

- ↑ George (2005), p. 82

- ↑ Gleijeses, Piero: Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959–1976 (The University of North Carolina Press) quoting: Steenkamp, Willem in: South Africa's Border War, 1966–1989, Gibraltar, 1989, p. 51-52; quoting: Spies, F. J. du Toit in. Operasie Savannah. Angola 1975–1976, Pretoria, 1989, p. 140 –143; quoting: du Preez, Sophia in: Avontuur in Angola. Die verhaal van Suid-Afrika se soldate in Angola 1975–1976, Pretoria, 1989, p. 121-122; quoting: de Villiers, PW, p. 259

- ↑ George (2005), p. 93

- ↑ George (2005), p. 94

- ↑ Spies, F. J. du Toit in. Operasie Savannah. Angola 1975–1976, Pretoria, 1989, p. 215

- ↑ George (2005), pp. 94–96

- ↑ Observer, December 7, 1975, p. 11

- ↑ Times, December 11, 1975, p. 7

- ↑ Gleijeses, Piero: Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959–1976 (The University of North Carolina Press) quoting: du Preez, Sophia in: Avontuur in Angola. Die verhaal van Suid-Afrika se soldate in Angola 1975–1976, Pretoria, 1989, p. 154-73; quoting: Spies, F. J. du Toit in. Operasie Savannah. Angola 1975–1976, Pretoria, 1989, p. 203–18

- ↑ Gleijeses, Piero: Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959–1976 (The University of North Carolina Press) quoting: du Preez, Sophia in: Avontuur in Angola. Die verhaal van Suid-Afrika se soldate in Angola 1975–1976, Pretoria, 1989, p. 186-201

- ↑ Foreign Broadcast Information Service (FBIS), 8, December 28, 1975, E3 (quoting Botha)

- ↑ Gleijeses, Piero: Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959–1976 (The University of North Carolina Press) quoting: Steenkamp, Willem in: South Africa's Border War 1966–1989, Gibraltar,1989, p. 55

- ↑ Rand Daily Mail, January 16

- ↑ Gleijeses, Piero: Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, (The University of North Carolina Press), p. 325

- ↑ Smith, Wayne: A Trap in Angola in: Foreign Policy No. 62, Spring 1986, p. 72, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- ↑ Gleijeses, Piero: Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959–1976 (The University of North Carolina Press) quoting: Secretary of State to all American Republic Diplomatic posts, December 20, 1975, NSA

- ↑ George (2005), p. 107

- ↑ Hallett, R. (1978, July). The South African Intervention in Angola, 1975–76. African Affairs, 77 (308), 347–386. Retrieved August 31, 2011, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/721839 p. 379

- ↑ Gleijeses, P. (2003). Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, Pretoria. Johannesburg,South Africa: Galago.p. 341

- 1 2 Diedericks, André (2007). Journey Without Boundaries (2nd ed.). Durban, South Africa: Just Done Productions Publishing (published 23 June 2007). ISBN 978-1-920169-58-9. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ↑ George (2005), pp. 102–103

- 1 2 George George (2005). The Cuban Intervention in Angola, 1965–1991: From Che Guevara to Cuito Cuanavale. Routledge. pp. 102–103. ISBN 0-415-35015-8.

- 1 2 The Battle for Bridge 14

- ↑ "Sentinel Projects: IN MEMORY OF THREE SPECIAL FORCES AND 32 BATTALION SOLDIERS". Sadf.sentinelprojects.com. Retrieved 2013-12-07.

- ↑ "Klantenservice | Online". Home.wanadoo.nl. Retrieved 2013-12-07.

- ↑ "File:Luso Airport Angola Dec 1975.jpg – Wikimedia Commons". Commons.wikimedia.org. Retrieved 2013-12-07.

- ↑ Bennett, Chris. Operation Savannah November 1975: Ambrizette (pdf). Just Done Productions Publishing. Retrieved 2007-09-26.

- ↑ Bennett, Chris (2006). Three Frigates – The South African Navy Comes of Age (2nd ed.). Durban, South Africa: Just Done Productions Publishing (published 1 June 2006). ISBN 978-1-920169-02-2. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ↑ Hamann, Hilton (2001). Days of the Generals. New Holland Publishers. p. 38.

- ↑ Clodfelter, Michael (2002). Warfare and Armed Conflicts- A Statistical Reference to Casualty and Other Figures, 1500-2000 2nEd. Jefferson: McFarland & Company. p. 626. ISBN 978-0786412044.

- ↑ Edward (2005) p.315

Further reading

- du Toit Spies, François Jacobus (1989). Operasie Savannah. Laserdruk. ISBN 0-621-12641-1.

- Steenkamp, Willem (1989). South Africa's border war, 1966–1989. Gibraltar: Ashanti Pub. ISBN 0620139676.

- "Operation Savannah: A Measure of SADF Decline, Resourcefulness and Modernisation". Scientia Militaria. 40 (3): 354–397. 2012. doi:10.5787/40-3-1042.

- "Battle of Bridge 14". Retrieved 26 March 2015.