Operation Tigerfish

Operation Tigerfish was the military code name in World War II for the air raid on Freiburg in the evening of 27 November 1944 by the Royal Air Force with about 2,800 dead.

The name Tigerfish goes back to Air Vice-Marshal Robert Saundby, an avid fisherman who codenamed all German cities "fitted" for carpet bombing with a Fish code.[1] Saundby was the deputy of Air Chief Marshal Arthur Harris, Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief of RAF Bomber Command.

Background

| Date of air raid[2] |

Number dropped bombs |

|---|---|

| 10.05.1940 | 69 |

| 03.10.1943 | 12 |

| 07.10.1943 | 7 |

| 09.09.1944 | only on-board-guns |

| 10.09.1944 | only on-board-guns |

| 12.09.1944 | 2 |

| 29.09.1944 | only on-board-guns |

| 07.10.1944 | only on-board-guns |

| 08.10.1944 | only on-board-guns |

| 03.11.1944 | 8 |

| 04.11.1944 | 21 |

| 21.11.1944 | 15 |

| 27.11.1944 | 14.525[3] |

| 02.12.1944 | 34 |

| 03.12.1944 | 49 |

| 17.12.1944 | 74 |

| 22.12.1944 | 5 |

| 25.12.1944 | only on-board-guns |

| 29.12.1944 | 13 |

| 30.12.1944 | 47 |

| 01.01.1945 | 32 |

| 04.01.1945 | 10 |

| 15.01.1945 | 59 |

| 08.02.1945 | 248 |

| 10.02.1945 | 44 |

| 13.02.1945 | 1 |

| 18.02.1945 | 18 |

| 21.02.1945 | 7 |

| 22.02.1945 | 36 |

| 24.02.1945 | 20 |

| 25.02.1945 | 1024 |

| 26.02.1945 | 79 |

| 28.02.1945 | 1861 |

| 04.03.1945 | 53 |

| 13.03.1945 | 24 |

| 16.03.1945 | 1801 |

After Freiburg was mistakenly bombed by the German Luftwaffe on 10 May 1940 when 57 people were killed, the city remained spared from attacks until October 1943.

For a long time people in Freiburg had lived in the hope that they would not have to suffer a major attack. The city was classified only as air protection location category 2 in 1935.[4] As a consequence Freiburg had to make arrangements for adequate protection of the population by the construction of shelters and bunkers without getting any financial resources from the state. The hope of being spared from bombing still existed, when air raids were made on nearby cities, because Freiburg was not included in the target list of the Allies at the forefront.

In autumn 1943, the Allies dropped leaflets in northern Germany that homeless people from the Reich would be welcome in the city. The intention was to trigger a movement of refugees to Freiburg. This propaganda campaign remained, however, without consequences.[5]

From 3 October 1943 there was the first light bombing.[5] Thus, on 7 October 1943, when aircraft of the U.S. Air Force (USAAF, 1st Bomb Division) bombed rail facilities of the city.

On 1 April 1944 the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) flew an attack on Ludwigshafen. Then the aircraft turned off, however, to bomb the planned secondary target Freiburg. Instead, the bombers mistakenly attacked the Swiss city Schaffhausen.

On 3 November 1944 the freight railway station and the airfield of Freiburg were the target of 16 bombers of the 9th U.S. tactical fleet. On 21 November 1944, there was a further attack.[6]

Target

In the city there was hardly any enterprises of military importance. The Bomber's Baedeker listed in 1944 Mez AG, Deutsche Acetate Kunstseiden A.G. „Rhodiaceta" and Hellige & Co. as well as the Gasworks of Freiburg as goals of category 3. Only the railway junction appears in Category 2. Purely military targets were not mentioned.[7]

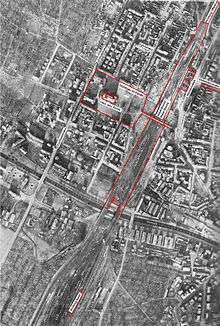

Freiburg came increasedly into the focus of the Allied Bomber Command when the front approached from the west to the frontier. Due to its convenient location on the Rhine Valley Railway and the Freiburg–Colmar railway via Breisach to the Alsace Freiburg played an increasingly important role for troop movements. The Allies assumed in 1943 that it would be possible for the Wehrmacht to move seven divisions from the Eastern to the Western Front within 12 to 14 days.[8] That is why General Eisenhower ordered on 22 November 1944 to attack railway and transportation hubs from the air. After a daylight attack of the Americans on Offenburg the British should bomb Freiburg the following day. Because the "transport connections bordered built-up areas",[9] Freiburg was considered particularly suitable for a carpet bombing according to the Area Bombing Directive, which aimed for the largescale destruction of residential areas. This is proven not least by the mission order that the target should be to destruct the city and the adjacent railway system.[10]

Attack

The preparation of the bombing on 27 November 1944 was made by 59 de Havilland Mosquito bombers of the No. 8 Pathfinder Group and was coordinated through a mobile oboe system in France.[12] The aim point was the intersection Habsburgerstrase / Bernhardstrase.[13] After the labeling of the target area with red markings the order had been given to mark the area with even larger amounts of red and green markings. The marking and bombing was coordinated by a master bomber. In the event that this would not have been audible by the bomber pilots, the mission order stipulated to drop as many bombs as possible. First bombs should be dropped on red, then red and green, then green and finally on yellow markings.[14]

Between 19.58 and 20.18 clock the Freiburg bombing was carried out by 292[15] Lancaster bombers of No. 1 Group RAF which dropped 3002 explosive (1,457 t) and 11,523 incendiary bombs and bombs mark (266 t) dropped.[16] Only one Lancaster bomber was lost. The cause for that could not be clarified definitely.[17]

Aftermath

Casualties

The death toll was 2,797, approximately 9,600 people were injured.[18] Among the dead were the theologian Johann Baptist Knebel, the artist Hermann Gehri and astrologer Elsbeth Ebertin.[19] After the bombing on 27 November 1944 many people left the city. On 31 December 1944, 63 962 people have been counted. In late April 1945, the low point of 57,974 people has been reached yet. It was only in early 1950 when the original population was reached again.[20]

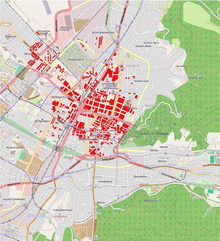

Destruction

Almost completely destroyed were the historic old town, the suburbs of Neuburg, Betzenhausen and Mooswald and the northern part of the Stühlinger. All in all about 30% of homes were destroyed or severely damaged.[21] Whole industries such as Hüttinger Elektronik, Grether & Cie. and M. Welte & Söhne were destroyed. Numerous historical buildings where destroyed by the attack. Almost all have been reconstructed:

- Old Church St. Louis (13th/19th century)

- Church of St. Martin (14th century)

- St. Conrad (built in 1929 by Brenzinger. & Cie. under Carl Anton Meckel, one of the first churches of concrete[22])

- Gerichtslaube (court loggia, 14th century)

- Basler Hof (1494/96)

- Kornhaus (grain house, 1498)

- Zum Walfisch (1514/16; all burnt, only facade and bay window rescued)

- Old town hall (1557/59)

- Peterhof (1585/87)

- University Church (17th century)

- St. Michael's Chapel (18th century)

- Deutschordenskommende (1768/73)

- Palais Sickingen (1769/73)

- Charles’s barracks (1773/76)

- Collegium Borromaeum (1823/26)

- Culture and Festival Hall at the city garden (built in 1854 by Friedrich Eisenlohr )[23]

- City Theatre (1905/10)

- Station including catenary and track systems)[24]

- Bertoldsbrunnen (1806 by Franz Xaver Hauser )

Only slightly damaged was the town's landmark, the Freiburg Minster.

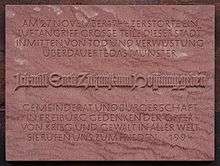

Commemoration

The victims of 27 November 1944 are remembered in Freiburg by various memorials and regular commemorative events.[25]

Remembrance

The victims of 27 November 1944 are commemorated in Freiburg by several memorials and regular commemoration ceremonies.

Memorials

- Tomb and memorial at the main cemetery: of the victims of the bombing 1664 could be buried in a tomb and memorial as well as in other graves in the main cemetery of Freiburg. The site was inaugurated on 27 November 1958 by Mayor Joseph Brandel.

- Memorial for the victims of the 1939-1945 war in the main cemetery: Next to the consecration hall of the main cemetery a cross with a figure, "The Mourner" by Richard Engelmann, remembers the victims of the bombing of Freiburg during the Second World War. After long negotiations and deliberations, the cross was inaugurated on 18 October 1951.

- On the west tower at the entrance to the Freiburg Minster the victims of the attack are commemorated and the slight damage to the cathedral by the otherwise devastating bomb attack is pointed out. This memorial plaque was erected in 1994 on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the bombing.

- As it is told that a drake in the municipal park warned before the bombing, the statue of a drake was created by Richard Bampi which was presented as a gift to the citizens of Freiburg by Mayor Wolfgang Hoffmann. The statue was inaugurated on 27 November 1953.

- A crucifix in the Deutschordensstraße which is at this point since 1963 bears the inscription: "In the year of the war 1944 during the great attack, the collegiate church Heiliggeiststift on Gauchstraße was destroyed and the thiscross considerably damaged. In 1957, the Heiliggeiststift was reconstructed at this place and the cross was erected here in 1963."

- On the archway at the main entrance of the University Hospital Freiburg is a plaque with the inscription: "Destroyed by enemy action on 27 November 1944, built again in 1945 -1953".

- On the building on Lehener Straße 11 in the suburb Stühlinger is a plaque commemorating the destruction of the enterprise M. Welte & Sons.

- At the main post office building on Eisenbahnstraße there is a plaque with the following text: "1272 the St. Clara convent was built here. In 1675 it had to give way to the city's fortifications. Under Heinrich von Stephan the post office was built here in 1878 and destroyed in a bomb attack on 27 November 1944. On that occasion 99 members of the post and telecommunications ministry were killed. The new building was built in 1961." At the entrance of the staircase of the building is also a great relief inside with the names of the 99 victims.

- In front of the Kollegiengebäude ( College Building) II of Freiburg University is a memorial donated by Herder Verlag. Two horizontal slabs bear the inscription: "In appreciation for the preservation of town and Minster on 27 November 1944 and in memory of the synagogue."

- After the foundation stone was laid on 15 November 1965 the new Bertoldsbrunnen was inaugurated on 27

November 1965. It bears the inscription: "1965 built on the site of the Bertoldsbrunnen of 1807 which was destroyed in 1944."

- For a very short time, from 10 July 1979 to 7 August 1979, on Kaiser-Joseph-Straße a more than five-meter high wooden figure of the artist Jurgen Goertz was unveiled as a memorial to commemorate the destruction of Freiburg.

- On the footbridge to the Castle Mountain, the Schlossbergsteg, there are several concrete reliefs of the artist are Emil Wachter from the year 1979. The motifs shown include the lettering Coventry, the year of the attack on Freiburg, a hand over Freiburg Minster as well as pictures of bomb-dropping aircraft and of Freiburg burning.

- On the keystone of the Minster tower a text by Reinhold Schneider reminds of the destruction of Freiburg on 27 November 1944.[26]

Commemoration

_6503.jpg)

The city of Freiburg commemorates the event with a wreath laying ceremony and other events. On the fiftieth anniversary an oratorio in Freiburg Minster, a commemoration ceremony as well as an exhibition of the City Archives took place.[27] [28] On Commemoration Day on 27 November 2004 the following events took place:[29]

- Photo Exhibition: Operation Tigerfish

- Exhibition: Air protection is necessary

- Screenings: Bombs on Freiburg

- Exhibition: Symbols of Remembrance

- Remembrance service

- Oratory: De Curru Igneo

- Lecture: How experienced women the war on the home front?

- Media exhibition at the City Library on Minster Square.

Furthermore, the Hosanna bell of Freiburg Minster rings on each anniversary at the time of the air raid.

Other commemorations

On the fiftieth anniversary city government and the Sparkasse Freiburg issued a commemorative medal with an image of the statue of the drake in the city park on the reverse.

Reception

The composer Julius Weismann processed in his choral work with soloists and orchestra Op. 151 The Watchmen (1946–49) besides the "horrible event(s) of the last decade," the destruction of his home town of Freiburg.[30]

"All of Freiburg, which had once had been a flourishing and brilliant town, consisted mostly of ruins, burning flavor and chimney stumps. The city was burnt completely, just as once in the Thirty Years' War" - HORST KRÜGER (1945)[31]

"Was three days in Freiburg; three quarters of the beautiful city, the whole city center, is a lump, the streets already (but not yet all) uncovered. - Churches, theaters, university, everything or almost everything lost. Gruesome sight of dead; among the ruins are often wreaths or more often crosses with inscriptions - people who are buried there. " - ALFRED DÖBLIN (1946)[32]

Further reading

- Jurgen Brauer and Hubert van Tuyll: The Age of the World Wars, 1914–1945: The Case of Diminishing Marginal Returns to the Strategic Bombing of Germany in World War II. In: Jurgen Brauer and Hubert van Tuyll: Castles, Battles, and Bombs. How Economics Explains Military History. ISBN 978-0-226-07163-3

- Christian Geinitz: Kriegsgedenken in Freiburg. Trauer – Kult – Verdrängung, Freiburg 1995 ISBN 3-928276-06-9

- Thomas Hammerich (editor): Zivilbevölkerung im Bombenkrieg : die Zerstörung Betzenhausens am 27. November 1944, Freiburg 2004 ISBN 3-9809961-0-7

- Kriegsopfer der Stadt Freiburg i. Br. 1939–1945, Freiburg 1954

- Günther Klugermann: Feuersturm über Freiburg: 27. November 1944, Gudensberg-Gleichen 2003 ISBN 3-8313-1335-0

- Stadt Freiburg (editor): Die Zerstörung Freiburgs am 27. November 1944. Augenzeugen berichten 1994, Freiburg 1994 ISBN 3-923288-14-X

- Stadt Freiburg (editor): Freiburg 1944–1994. Zerstörung und Wiederaufbau, Waldkirch 1994 ISBN 3-87885-293-2

- Stadt Freiburg (editor): Memento – Freiburg 27.11.1944. Chronik eines Gedenkens 27.11.1994, Freiburg 1995, ISBN 3-923288-15-8

- Gerd R. Ueberschär: Freiburg im Luftkrieg 1939–1945, Freiburg/Munich 1990 ISBN 3-87640-332-4

- Walter Vetter (editor): Freiburg in Trümmern 1944–1952, Vol. 1, Freiburg 1982 ISBN 3-7930-0283-7

- Walter Vetter (editor): Freiburg in Trümmern 1944–1952, Vol. 2, Freiburg 1984 ISBN 3-7930-0485-6

- Elmar Wiedeking: Im Gesicht des Feindes den Menschen sehen. Der Absturz einer Lancaster über Freiburg und das Schicksal ihrer Besatzung. In: Schau-ins-Land 127 (2008), P. 157-172

Filmography

- Bomben auf Freiburg (bombs on Freiburg). Documentary, 63 min. Directed by Adam Dirk and Hans-Peter Hagmann. Germany 2004

- Zerstörung, Wiederaufbau, Alltag: Freiburg 1940–1950 (destruction, reconstruction, everyday life: Freiburg 1940-1950). Revised documentary by Rudolf Langwieler, 38 min. Germany 2010

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Operation Tigerfish. |

References

- ↑ Data sheet Fishcodes.

- ↑ Walter Vetter (Hrsg.): Freiburg in Trümmern (in ruins) 1944–1952, Rombach, Freiburg. p. 171: „in accordance with a chart elaborated during the war with estimated numbers."

- ↑ This number is based on: Gerd R. Ueberschär: Freiburg im Luftkrieg (during the air raids) 1939–1945. Freiburg im Breisgau/München, 1990, p. 242. ISBN 3-87640-332-4. Walter Vetter gives an estimated number of 50.000 bombs.

- ↑ Heiko Haumann,Hans Schadek (Hrsg.): Geschichte der Stadt Freiburg. Band 3: Von der badischen Herrschaft bis zur Gegenwart. Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-8062-1635-5. S. 359.

- 1 2 Heiko Haumann, Hans Schadek (Hrsg.): Geschichte der Stadt Freiburg (History of Freiburg) Volume 3: Von der badischen Herrschaft bis zur Gegenwart (From the Badish rule to the present day) Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-8062-1635-5, p. 360

- ↑ Gerd R. Ueberschär: Freiburg im Luftkrieg (during the air raids) 1939–1945. Freiburg im Breisgau/München, 1990. p. 181 et seqq. ISBN 3-87640-332-4.

- ↑ cf. the extract from the so-called Bomber’s Baedeker in: Gerd R. Ueberschär: Freiburg im Luftkrieg (during the air raids) 1939–1945. Freiburg im Breisgau/Munich, 1990. P. 107. ISBN 3-87640-332-4.

- ↑ The Casablanca Conference, III, P. 539. In: United States Department of State / Foreign relations of the UnitedStates. The Conferences at Washington, 1941–1942, and Casablanca, 1943. (1941–1943)

- ↑ Gerd R. Ueberschär: Freiburg im Luftkrieg 1939–1945. Freiburg im Breisgau/Munich, 1990. P. 196 et seqq. ISBN 3-87640-332-4.

- ↑ Gerd R. Ueberschär: Freiburg im Luftkrieg (during the air raids) 1939–1945. Freiburg im Breisgau/Munich, 1990. ISBN 3-87640-332-4.

- ↑ Gerd R. Ueberschär: Freiburg im Luftkrieg 1939–1945. Freiburg im Breisgau/Munich, 1990. Abb. 127. ISBN 3-87640-332-4.

- ↑ raf.mod.uk: RAF History - Bomber Command 60th Anniversary, Zugriff am 27. Januar 2010

- ↑ Gerd R. Ueberschär: Freiburg im Luftkrieg 1939–1945. Freiburg im Breisgau/Munich, 1990. S. 225. ISBN 3-87640-332-4.

- ↑ cf.: Gerd R. Ueberschär: Freiburg im Luftkrieg 1939–1945. Freiburg im Breisgau/Munich, 1990. S. 219, P. 398 Ill. 123. ISBN 3-87640-332-4.

- ↑ Stadt Freiburg: Tausende Spreng- und Brandbomben verwüsteten am 27.11.1944 die Stadt (thousands of demolition bombs and firebombs destroyed the town on 27/11/1944) in: Amtsblatt (official gazette) of 29 November 2004

- ↑ Gerd R. Ueberschär: Freiburg im Luftkrieg (during the air raids) 1939–1945. Freiburg im Breisgau/Munich, 1990. S. 242. ISBN 3-87640-332-4.

- ↑ Gerd R. Ueberschär: Freiburg im Luftkrieg (during the air raids) 1939–1945. Freiburg im Breisgau/Munich, 1990. P. 237. ISBN 3-87640-332-4.

- ↑ Heiko Haumann, Hans Schadek (Hrsg.): Geschichte der Stadt Freiburg. Band 3: Von der badischen Herrschaft bis zur Gegenwart. P 361. Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-8062-1635-5

- ↑ For a name liste of the victims see: Kriegsopfer der Stadt (war victims of the city) Freiburg i. Br. 1939–1945, Freiburg 1954

- ↑ Gerd R. Ueberschär: Freiburg im Luftkrieg (during the air raids) 1939–1945. Freiburg im Breisgau/Munich, 1990. S. 380. ISBN 3-87640-332-4.

- ↑ Ueberschär, p. 381.

- ↑ Werner Wolf-Holzäpfel: Der Architekt Max Meckel 1847–1910. Studien zur Architektur und zum Kirchenbau des Historismus in Deutschland., Josef Fink, Lindenberg 2000, ISBN 3-933784-62-X, S. 257 f.

- ↑ Stadt Freiburg: Der neue Hauptbahnhof Freiburg, Presse und Informationsamt/Stadtplanungsamt, Freiburg Juli 2001, S. 55

- ↑ Hans-Wolfgang Scharf, Burkhard Wollny: Die Höllentalbahn. Von Freiburg in den Schwarzwald. Eisenbahn-Kurier-Verlag, Freiburg im Breisgau 1987, ISBN 3-88255-780-X, S. 128

- ↑ Ute Scherb: Wir bekommen die Denkmäler, die wir verdienen (we receive the monuments we deserve). Freiburger Monumente im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert (monuments of Freiburg of the 19th and 20th centuries). Stadtarchiv (town archive) Freiburg im Breisgau 2005. ISBN 3-923272-31-6. S. 196ff.

- ↑ Keystone plaque of the cathedral platform. Font design by Reinhold Schneider Circulating text: WRITTEN TEN MONTHS BEFORE THE AIR RAID ON FREIBURG * ON 27 NOVEMBER 1944 FREIBURG WAS DESTROYED. BUT THE MINSTER WAS SAVED. Text on the plaque: STAND INDESTRUCTIBLE IN THE MIND/ YOU BIG PRAYER FAITH POWERFUL TIME/ HOW YOU ARE TRANSFORMED BY THE GLORY OF THE DAY/ WHEN THE GLORY OF THE DAY HAS LONG DIED DOWN// HOW WILL I ASK THAT I FAITHFULLY WATCH/ THE SACRED YOU RADIATE IN THE LINING/ AND WILL BE A TOWER IN THE DARK/ THE BEARER OF THE LIGHT WHICH/ BLOOMED TO THE WORLD/ AND SHOULD I FALL IN THE GREAT STORM/ BE IT AS AN OFFERING THAT TOWERS STILL WILL RISE/ AND THAT MY PEOPLE BE THE TRUTH'S TORCH/ YOU WILL NOT FALL MY BELOVED TOWER/ BUT IF THE JUDGE'S FLASHES BURST YOU/ RISE IN PRAYERS BOLDER FROM THE EARTH// </poem> REINHOLD SCHNEIDER * THE TOWER OF THE MINSTER

- ↑ Beschluss-Vorlage des Gemeinderates Freiburg, DRUCKSACHE G-93/047 (PDF)

- ↑ Beschluss zur Vorlage DRUCKSACHE G-93/047 (PDF)

- ↑ Amtsblatt Freiburg, 29. November 2004 (PDF).

- ↑ Program of debut performance, Duisburg 11 January 1950

- ↑ Horst Krüger: Freiburger Anfänge In: Dietrich Kayer (Hrsg.): Ortsbeschreibung – Autoren sehen Freiburg Rombach, Freiburg im Breisgau 1980, ISBN 978-3-7930-0359-5; quoted from Maria Rayers: Freiburg in alten und neuen Reisebeschreibungen (in old and new travelogues), Droste, Düsseldorf 1991, ISBN 978-3-7700-0932-9

- ↑ Alfred Döblin: Briefe (letters), Walter-Verlag, Olten and Freiburg im Breisgau 1970, ISBN 978-3-423-02444-0, quoted from Maria Rayers: Freiburg in alten und neuen Reisebeschreibungen (in old and new travelogues), Droste, Düsseldorf 1991, ISBN 978-3-7700-0932-9

Coordinates: 48°00′10″N 7°51′12″E / 48.0027°N 7.8534°E