Ordered ring

In abstract algebra, an ordered ring is a (usually commutative) ring R with a total order ≤ such that for all a, b, and c in R:[1]

- if a ≤ b then a + c ≤ b + c.

- if 0 ≤ a and 0 ≤ b then 0 ≤ ab.

Examples

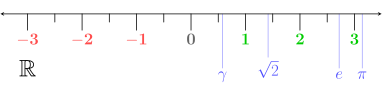

Ordered rings are familiar from arithmetic. Examples include the integers, the rationals and the real numbers.[2] (The rationals and reals in fact form ordered fields.) The complex numbers, in contrast, do not form an ordered ring or field, because there is no inherent order relationship between the elements 1 and i.

Positive elements

In analogy with the real numbers, we call an element c ≠ 0 of an ordered ring positive if 0 ≤ c, and negative if c ≤ 0. The element c = 0 is considered to be neither positive nor negative.

The set of positive elements of an ordered ring R is often denoted by R+. An alternative notation, favored in some disciplines, is to use R+ for the set of nonnegative elements, and R++ for the set of positive elements.

Absolute value

If a is an element of an ordered ring R, then the absolute value of a, denoted |a|, is defined thus:

where -a is the additive inverse of a and 0 is the additive identity element.

Discrete ordered rings

A discrete ordered ring or discretely ordered ring is an ordered ring in which there is no element between 0 and 1. The integers are a discrete ordered ring, but the rational numbers are not.

Basic properties

For all a, b and c in R:

- If a ≤ b and 0 ≤ c, then ac ≤ bc.[3] This property is sometimes used to define ordered rings instead of the second property in the definition above.

- |ab| = |a| |b|.[4]

- An ordered ring that is not trivial is infinite.[5]

- Exactly one of the following is true: a is positive, -a is positive, or a = 0.[6] This property follows from the fact that ordered rings are abelian, linearly ordered groups with respect to addition.

- An ordered ring R has no zero divisors if and only if the positive ring elements are closed under multiplication (i.e. if a and b are positive, then so is ab).[7]

- In an ordered ring, no negative element is a square.[8] This is because if a ≠ 0 and a = b2 then b ≠ 0 and a = (-b )2; as either b or -b is positive, a must be positive.

Notes

The list below includes references to theorems formally verified by the IsarMathLib project.

- ↑ Lam, T. Y. (1983), Orderings, valuations and quadratic forms, CBMS Regional Conference Series in Mathematics, 52, American Mathematical Society, ISBN 0-8218-0702-1, Zbl 0516.12001

- ↑

- Lam, T. Y. (2001), A first course in noncommutative rings, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 131 (2nd ed.), New York: Springer-Verlag, pp. xx+385, ISBN 0-387-95183-0, MR 1838439, Zbl 0980.16001

- ↑ OrdRing_ZF_1_L9

- ↑ OrdRing_ZF_2_L5

- ↑ ord_ring_infinite

- ↑ OrdRing_ZF_3_L2, see also OrdGroup_decomp

- ↑ OrdRing_ZF_3_L3

- ↑ OrdRing_ZF_1_L12