Ornithocheirus

| Ornithocheirus Temporal range: Late Cretaceous, 110 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

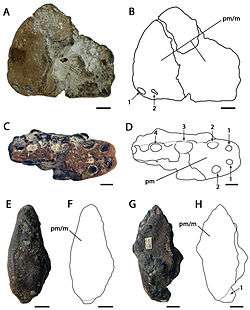

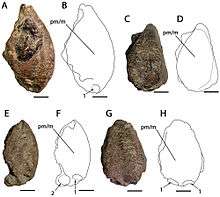

| Holotype of O. simus, CAMSM B54428, and referred specimen CAMSM B54552 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | †Pterosauria |

| Suborder: | †Pterodactyloidea |

| Family: | †Ornithocheiridae |

| Subfamily: | †Ornithocheirinae Seeley, 1870 |

| Genus: | †Ornithocheirus Seeley, 1869 |

| Type species | |

| †Pterodactylus simus Owen, 1861 | |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Ornithocheirus (from Ancient Greek "ὄρνις", meaning bird, and "χεῖρ", meaning hand) is a pterosaur genus known from fragmentary fossil remains uncovered from sediments in the UK.

Several species have been referred to the genus, most of which are now considered as dubious species, or members of different genera, and the genus is now often considered to include only the type species, Ornithocheirus simus. Species have been referred to Ornithocheirus from the mid-Cretaceous period of both Europe and South America, but O. simus is known only from the UK. Because O. simus was originally named based on poorly preserved fossil material, the genus Ornithocheirus has suffered enduring problems of zoological nomenclature.

Fossil remains of Ornithocheirus have been recovered mainly from the Cambridge Greensand of England, dating to the beginning of the Albian stage of the late Cretaceous period, about 110 million years ago.[1] Additional fossils from the Santana Formation of Brazil are sometimes classified as species of Ornithocheirus,[2] but have also been placed in their own genera, most notably Tropeognathus.

Description

O. simus is only known from fragmentary jaw tips. It bore a distinctive convex "keeled" crest on its snout.[3] Ornithocheirus had relatively narrow jaw tips compared to Anhanguera and Coloborhynchus, which had prominently-expanded rosettes of teeth. Also unlike related pterosaurs, the teeth of Ornithocheirus were mostly vertical, rather than set at an outward-pointing angle.[3]

Discovery and naming

During the 19th century, in England many fragmentary pterosaur fossils were found in the Cambridge Greensand, a layer from the early Cretaceous, that had originated as a sandy seabed. Decomposing pterosaur cadavers, floating on the sea surface, had gradually lost individual bones that sank to the bottom of the sea. Water currents then moved the bones around, eroding and polishing them, until they were at last covered by more sand and fossilised. Even the largest of these remains were damaged and difficult to interpret. They had been assigned to the genus Pterodactylus, as was common for any pterosaur species described in the early and middle 19th century.

Young researcher Harry Govier Seeley was commissioned to bring order to the pterosaur collection of the Sedgwick Museum in Cambridge. He soon concluded that it was best to create a new genus for the Cambridge Greensand material that he named Ornithocheirus, "bird hand", as he in this period still considered pterosaurs to be the direct ancestors of birds, and assumed the hand of the genus to represent a transitional stage in the evolution towards the bird hand. To distinguish the best pieces in the collection, and partly because they had already been described as species by other scientists, he in 1869 and 1870 each gave them a separate species name: O. simus, O. woodwardi, O. oxyrhinus, O. carteri, O. platyrhinus, O. sedgwickii, O. crassidens, O. capito, O. eurygnathus, O. reedi, O. cuvieri, O. scaphorhynchus, O. brachyrhinus, O. colorhinus, O. dentatus, O. denticulatus, O. enchorhynchus, O. xyphorhynchus, O. fittoni, O. nasutus, O. polyodon, O. compressirostris, O. tenuirostris, O. machaerorhynchus, O. platystomus, O. microdon, O. oweni and O. huxleyi, thus 28 in total. As yet Seeley did not designate a type species.

When Seeley published his conclusions in his 1870 book The Ornithosauria, this provoked a reaction by the leading British paleontologist of his day, Richard Owen. Owen was not an evolutionist and he therefore considered the name Ornithocheirus to be inappropriate; he also thought it was possible to distinguish two main types within the material, based on differences in snout form and tooth position — the best fossils consisted of jaw fragments. He in 1874 created two new genera: Coloborhynchus and Criorhynchus. Coloborhynchus, "maimed beak", comprised a new species, Coloborhynchus clavirostris, the type species, and two species reassigned from Ornithocheirus: C. sedgwickii and C. cuvieri. Criorhynchus, "ram beak", consisted entirely of former Ornithocheirus species: the type species Criorhynchus simus and furthermore C. eurygnathus, C. capito, C. platystomus, C. crassidens and C. reedi.

Seeley did not accept Owen's position. In 1881 he designated O. simus the type species of Ornithocheirus and named a new species O. bunzeli. In 1888 Edward Newton renamed several existing species names into Ornithocheirus, as Ornithocheirus clavirostris, O. daviesii, O. sagittirostris, O. validus, O. giganteus, O. clifti, O. diomedeus, O. nobilis, O. curtus, O. umbrosus, O. harpyia, O. macrorhinus and O. hlavaci.

In 1914 Reginald Walter Hooley made a new attempt to structure the large number of species. Keeping the name Ornithocheirus, he added to it Owen's Criorhynchus, in which however Coloborhynchus was sunk, and to allow for a greater differentiation created two new genera, again based on jaw form: Lonchodectes and Amblydectes. Lonchodectes, "lance biter", comprised L. compressirostris, L. giganteus and L. daviesii. Amblydectes, "blunt biter", consisted of A. platystomus, A. crassidens and A. eurygnathus. However, Hooley's classification was rarely applied later in the century, when it became common to subsume all the poorly preserved and confusing material under the name Ornithocheirus. A Russian-language overview of Pterosauria in 1964 designated P. compressirostris the type species of Ornithocheirus, which was followed by Kuhn (1967) and Wellnhofer (1978), yet those authors were unaware that Seeley (1881) made P. simus the type species of Ornithocheirus.[4][5][6]

From the seventies onwards many new pterosaur fossils were found in Brazil in deposits slightly older than the Cambridge Greensand, 110 million years old. Unlike the English material, these new finds included some of the best preserved large pterosaur skeletons and several new genera names were given to them, such as Anhanguera. This situation caused a renewed interest in the Ornithocheirus material and the validity of the several names based on it, for it might be possible that it could by more detailed studies be established that the Brazilian pterosaurs were actually junior synonyms of the European types. Several European researchers concluded that this was indeed the case. Unwin revived Coloborhynchus and Michael Fastnacht Criorhynchus, each author ascribing Brazilian species to these genera. However, in 2000 Unwin stated that Criorhynchus could not be valid. Referring to Seeley's designation of 1881 he considered Ornithocheirus simus, holotype CAMSM B.54428, to be the type species. This also made it possible to revive Lonchodectes, using as type the former O. compressirostris, which then became L. compressirostris.

As a result, though over forty species have been named in the genus Ornithocheirus over the years, only O. simus is currently considered valid by all pterosaur researchers. Tropeognathus mesembrinus named by Peter Wellnhofer in 1987 was assigned to Ornithocheirus by David Unwin in 2003 (making Tropeognathus a junior synonym),[7] but as Anhanguera mesembrinus by Alexander Kellner in 1989, Coloborhynchus mesembrinus by André Veldmeijer in 1998 and Criorhynchus mesembrinus by Michael Fastnacht in 2001. Even earlier, in 2001, Unwin had referred the "Tropeognathus" material to O. simus in which he was followed by Veldmeijer; however the latter overlooked the fact that O. simus is the type species in favor of O. compressirostris (alternately Lonchodectes), and used the names Criorhynchus simus and Cr. mesembrinus.[8]

Formerly assigned species

In 2013, Rodrigues and Kellner found Ornithocheirus to be monotypic, containing only O. simus, and placed most other species in other genera, or declared them nomina dubia. They also considered O. platyrhinus a junior synonym of O. simus.[9]

Misassigned species:

- O. compressirostris (Hooley, 1914) = Pterodactylus compressirostris Owen, 1851 [now classified as Lonchodectes]

- O. crassidens Seeley, 1870 [now classified as Amblydectes]

- O. cuvieri (Seeley, 1870) = Pterodactylus cuvieri Bowerbank, 1851 [now classified as Cimoliopterus]

- O. curtus (Hooley, 1914) = Pterodactylus curtus Owen, 1874

- O. giganteus (Owen, 1979) = Pterodactylus giganteus Bowerbank, 1846 [now classified as Lonchodraco]

- "O." hilsensis Koken, 1883 = indeterminate at Neotheropoda[10]

- O. mesembrinus (Wellnhofer, 1987) = Tropeognathus mesembrinus Wellnfofer, 1987

- O. nobilis (Owen, 1869) = Pterodactylus nobilis Owen 1869

- O. simus (Owen, 1861) [originally Pterodactylus] (type)

- O. sedgwicki (Owen, 1859) = Pterodactylus sedgwickii Owen 1859 [now classified as Camposipterus]

- "O." wiedenrothi Wild, 1990 = possibly a relative of Lonchodectes[11]

Cimoliornis diomedeus, Cretornis hlavatschi, and Palaeornis clifti, originally misidentified as birds, were once referred to Ornithocheirus in the past, but recent papers have found them to be distinct; Cimoliornis may be closer to azhdarchoidea,[12] Cretornis is a valid genus of azhdarchid,[13][14] and Palaeornis was shown to be a lonchodectid in 2009.[15] O. buenzeli (Bunzel 1871, often misspelled and incorrectly attributed as O. bunzeli, Seeley 1881), cited in the past as evidence of Late Cretaceous ornithocheirids,[16] has since been re-identified as a likely azhdarchid as well.[17]

Classification

Below is a cladogram showing the phylogenetic placement of this genus within Pteranodontia from Andres and Myers (2013).[18]

| Pteranodontia |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

In popular culture

A large pterosaur identified as Ornithocheirus was featured in an episode of the award-winning BBC television program Walking with Dinosaurs.[2] The episode depicted a large ornithocheirid of the Santana Formation of Brazil, Ornithocheirus mesembrinus, which is currently now classified in the distinct genus Tropeognathus.[19]

See also

Paleontology portal

Paleontology portal

References

- Haines, T., and Chambers, P. (2006). The Complete Guide to Prehistoric Life. Canada: Firefly Books Ltd.

Notes

- ↑ Vullo, R.; Neraudeau, D. (2009). "Pterosaur Remains from the Cenomanian (Late Cretaceous) Paralic Deposits of Charentes, Western France". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (1): 277–282. doi:10.1671/039.029.0123.

- 1 2 Unwin, David M. (2006). The Pterosaurs: From Deep Time. New York: Pi Press. p. 246. ISBN 0-13-146308-X.

- 1 2 Fastnacht, M (2001). "First record of Coloborhynchus (Pterosauria) from the Santana Formation (Lower Cretaceous) of the Chapada do Araripe of Brazil". Paläontologisches Zeitschrift. 75: 23–36. doi:10.1007/bf03022595.

- ↑ Khozatskii LI, Yur’ev KB. (1964) [Pterosauria]. In: Orlov JA. (Ed.). Osnovy Paleontologii 12 [Amphibians, Reptiles, Birds].Izdatel’stvo Nauka, Moscow: 589-603

- ↑ Kuhn O. (1967) Die fossile Wirbeltierklasse Pterosauria. Verlag Oeben, Krailling bei München, 52 pp.

- ↑ Wellnhofer P. (1978) Pterosauria. Handbuch der Paläoherpetologie, Teil 19. Gustav Fischer Verlag, Stuttgart and New York, 82 pp.

- ↑ http://dml.cmnh.org/2003Sep/msg00388.html

- ↑ Veldmeijer, A.J. (2006). "Toothed pterosaurs from the Santana Formation (Cretaceous; Aptian-Albian) of northeastern Brazil. A reappraisal on the basis of newly described material." Tekst. – Proefschrift Universiteit Utrecht.

- ↑ Rodrigues, T.; Kellner, A. (2013). "Taxonomic review of the Ornithocheirus complex (Pterosauria) from the Cretaceous of England". ZooKeys. 308: 1–112. doi:10.3897/zookeys.308.5559. PMC 3689139

. PMID 23794925.

. PMID 23794925. - ↑ http://theropoddatabase.com/Neotheropoda.htm

- ↑ http://brianandres.myweb.usf.edu/The_Pterosauria/pTwitter/Entries/2013/5/23_Rio_Ptero_2013_-_International_Symposium_on_Pterosaurs_files/Ford%20(2013A).pdf

- ↑ Martill, D.M. 2010. The early history of pterosaur discovery in Great Britain. In: Moody, R., Bueefetaut, E., Naish, D. & Martill, D.M. (eds) Dinosaurs and other extinct saurians. Geological Society, London, Special Publication, 343, 20–45.

- ↑ Averianov, A.O. (2010). "The osteology of Azhdarcho lancicollis Nessov, 1984 (Pterosauria, Azhdarchidae) from the Late Cretaceous of Uzbekistan" (PDF). Proceedings of the Zoological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences. 314 (3): 246–317.

- ↑ Averianov, A.; Ekrt, B. (2015). "Cretornis hlavaci Frič, 1881 from the Upper Cretaceous of Czech Republic (Pterosauria, Azhdarchoidea)". Cretaceous Research. 55: 164. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2015.02.011.

- ↑ Witton, M.P.; Martill, D.M.; Green, M. (2009). "On pterodactyloid diversity in the British Wealden (Lower Cretaceous) and a reappraisal of "Palaeornis" cliftii Mantell, 1844". Cretaceous Research. 30: 676–686. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2008.12.004.

- ↑ Federico L. Agnolin and David Varricchio (2012). "Systematic reinterpretation of Piksi barbarulna Varricchio, 2002 from the Two Medicine Formation (Upper Cretaceous) of Western USA (Montana) as a pterosaur rather than a bird" (PDF). Geodiversitas. 34 (4): 883–894. doi:10.5252/g2012n4a10.

- ↑ Buffetaut, E.; Psi, A.; Prondvai, E. (2011). "The pterosaurian remains from the Grünbach Formation (Campanian, Gosau Group) of Austria: a reappraisal of Ornithocheirus buenzeli". Geological Magazine. 148 (2): 334–339. doi:10.1017/S0016756810000981.

- ↑ Andres, B.; Myers, T. S. (2013). "Lone Star Pterosaurs". Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 103: 1. doi:10.1017/S1755691013000303.

- ↑ Haines, T., 1999, "Walking with Dinosaurs": A Natural History, BBC Books, p. 158