Oxford University Museum of Natural History

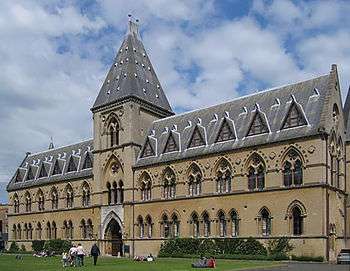

Front view of Oxford University Museum | |

Oxford University Museum of Natural History | |

| Established | 1850 |

|---|---|

| Location | Parks Road, Oxford, England |

| Coordinates | 51°45′31″N 1°15′21″W / 51.7586°N 1.2557°W |

| Type | University museum of natural history |

| Website | www.oum.ox.ac.uk |

The Oxford University Museum of Natural History, sometimes known simply as the Oxford University Museum or OUMNH, is a museum displaying many of the University of Oxford's natural history specimens, located on Parks Road in Oxford, England. It also contains a lecture theatre which is used by the University's chemistry, zoology and mathematics departments. The University Museum provides the only access into the adjoining Pitt Rivers Museum.

History

The University's Honour School of Natural Science started in 1850, but the facilities for teaching were scattered around the city of Oxford in the various colleges. The University's collection of anatomical and natural history specimens were similarly spread around the city.

Regius Professor of Medicine, Sir Henry Acland, initiated the construction of the museum between 1855 and 1860, to bring together all the aspects of science around a central display area. In 1858, Acland gave a lecture on the museum, setting forth the reason for the building's construction. He viewed that the University had been one-sided in the forms of study it offered—chiefly theology, philosophy, the classics and history—and that the opportunity should be offered to learn of the natural world and obtain the "knowledge of the great material design of which the Supreme Master-Worker has made us a constituent part". This idea, of Nature as the Second Book of God, was common in the 19th century.[1]

The construction of the building was accomplished through money earned from the sale of Bibles.[2] Several departments moved within the building—astronomy, geometry, experimental physics, mineralogy, chemistry, geology, zoology, anatomy, physiology and medicine. As the departments grew in size over the years, they moved to new locations along South Parks Road, which remains the home of the University's science departments.

The last department to leave the building was the entomology department, which moved into the zoology building in 1978. However, there is still a working entomology laboratory on the first floor of the museum building.

Between 1885 and 1886 a new building to the east of the museum was constructed to house the ethnological collections of General Augustus Pitt Rivers—the Pitt Rivers Museum. In 19th-century thinking, it was very important to separate objects made by the hand of God (natural history) from objects made by the hand of man (anthropology).[3]

The largest portion of the museum's collections consist of the natural history specimens from the Ashmolean Museum, including the specimens collected by John Tradescant the elder and his son of the same name, William Burchell and geologist William Buckland. The Christ Church Museum donated its osteological and physiological specimens, many of which were collected by Acland.

The building

The neo-Gothic building was designed by the Irish architects Thomas Newenham Deane and Benjamin Woodward. The museum's design was directly influenced by the writings of critic John Ruskin, who involved himself by making various suggestions to Woodward during construction. Construction began in 1855, and the building was ready for occupancy in 1860. The adjoining building that houses the Pitt Rivers Museum was the work of Thomas Manly Deane, son of Thomas Newenham Deane. It was built between 1885 and 1886.

The museum consists of a large square court with a glass roof, supported by cast iron pillars, which divide the court into three aisles. Cloistered arcades run around the ground and first floor of the building, with stone columns each made from a different British stone, selected by geologist John Phillips (the Keeper of the Museum). The ornamentation of the stonework and iron pillars incorporates natural forms such as leaves and branches, combining the Pre-Raphaelite style with the scientific role of the building.

Statues of eminent men of science stand around the ground floor of the court—from Aristotle and Bacon through to Darwin and Linnaeus. Although the University paid for the construction of the building, the ornamentation was funded by public subscription, and much of it remains incomplete. The Irish stone carvers O'Shea and Whelan had been employed to create lively freehand carvings in the Gothic manner. When funding dried up, they offered to work unpaid, but they were accused by members of the University Convocation of "defacing" the building by adding unauthorised work. According to Acland, the O'Shea brothers responded by caricaturing the members of Convocation as parrots and owls in the carving over the building's entrance. Acland insists that he forced them to remove the heads from these carvings.[4]

Significant events

The 1860 evolution debate

A significant debate in the history of evolutionary biology took place in the museum in 1860 at a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science.[5] Representatives of the Church and science debated the subject of evolution, and the event is often viewed as symbolising the defeat of a literalist interpretation of the Genesis creation narrative. However, there are few eye-witness accounts of the debate, and most accounts of the debate were written by scientists. [6][7]

Thomas Huxley and Samuel Wilberforce, the Bishop of Oxford, are generally cast as the main protagonists in the debate. Huxley was a keen scientist and a staunch supporter of Darwin's theories. Wilberforce had supported the construction of the museum as the centre for the science departments, for the study of the wonders of God's creations.

On the Wednesday of the meeting, 27 June 1860, botanist Charles Daubeny presented a paper on plant sexuality, which made reference to Darwin's theory of natural selection. Richard Owen, a zoologist who believed that evolution was governed by divine influence, criticised the theory pointing out that the brain of the gorilla was more different from that of man than that of other primates. Huxley stated that he would respond to this comment in print, and declined to continue the debate. However, rumours began to spread that the Bishop of Oxford would be attending the conference on the following Saturday.

Initially, Huxley was planning to avoid the bishop's speech. However, evolutionist Robert Chambers convinced him to stay.

Wilberforce's speech on 30 June 1860 was good-humoured and witty, but was an unfair attack on Darwinism, ending in the now infamous question to Huxley of whether "it was through his grandfather or grandmother that he claimed descent from a monkey." Some commentators suggested that this question was written by Owen, and others suggested that the bishop was taught by Owen. (Owen and Wilberforce had known each other since childhood.)

Wilberforce is purported to have turned to his neighbour, chemist Professor Brodie and exclaiming, "The Lord has delivered him into mine hands." When Huxley spoke, he responded that he had heard nothing from Wilberforce to prejudice Darwin's arguments, which still provided the best explanation of the origin of species yet advanced. He ended with the equally famous response to Wilberforce's question, that he had "no need to be ashamed of having an ape for his grandfather, but that he would be ashamed of having for an ancestor a man of restless and versatile interest who distracts the attention of his hearers from the real point at issue by eloquent digression and skilled appeals to religious prejudice."

However it seems unlikely that the debate was as spectacular as traditionally suggested – contemporary accounts by journalists do not make mention of the words that have become such notable quotations. Additionally, contemporary accounts suggest that it was not Huxley, but Sir Joseph Hooker who most vocally defended Darwinism at the meeting.

While all the accounts of the event suggest that the supporters of Darwinism were the most persuasive, it seems likely that the exact nature of the debate was made more sensational in the reports of Huxley's supporters to encourage further support for Darwin's theories.[8]

The 1894 demonstration of wireless telegraphy

The first public demonstration of wireless telegraphy took place in the lecture theatre of the museum on 14 August 1894, carried out by Professor Oliver Lodge. A radio signal was sent from the neighbouring Clarendon Laboratory building, and received by apparatus in the lecture theatre.

Charles Dodgson and the dodo

Today the head and foot of a dodo displayed at the museum are the most complete remains of a single dodo anywhere in the world. Many museums have complete dodo skeletons, but these are composed of the bones of several individuals. The museum also displays a 1651 painting of a dodo by Flemish artist, Jan Savery.

Charles Dodgson, better known by his pen-name Lewis Carroll, was a regular visitor to the museum, and Savery's painting is likely to have influenced the character of the Dodo in Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland.

The museum today

The museum has free entrance, is open daily from 10am to 5pm, and attracts over 670,000 visitors a year, including over 35,000 school children on organised visits.

The museum collections are divided into three sections: Earth Collections covering the Palaeontological collections and the mineral and rock collections, Life Collections which include zoological and entomological collections, and the Archive Collections. The museum is led by a Director (currently Professor Paul Smith (formerly Head of the School of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences at the University of Birmingham)), who succeeded Professor Jim Kennedy in 2011, and there are education, outreach, IT, library, conservation and technical staff.

Since 1997 the museum has benefited from external funding, from Government and private sources, and undertaken a renewal of its displays. As well as central exhibits featuring the dodo and dinosaurs, there are sets of displays with contemporary designs but within restored Victorian cabinets, on a variety of themes: Evolution, Primates, the History of Life, Vertebrates, Invertebrates and Rocks & Minerals. There are also a number of popular touchable items, which include Mandy the Shetland Pony, a stuffed leopard and other taxidermy. Additionally there is a meteorite and large fossils and minerals. Visitors can also see large dinosaur reconstructions and a procession of mammal skeletons.

A famous group of ichnites was found in a limestone quarry at Ardley, 20 km northeast of Oxford, in 1997. They were thought to have been made by Megalosaurus and possibly Cetiosaurus. There are replicas of some of these footprints, set across the front lawn of the museum.

The Hope Entomological Collections, numbering over 5 million specimens are held by the Museum. The Hope Department was founded by Frederick William Hope and the first appointed curator of the collections was John Obadiah Westwood. Many important insect and arachnid specimens from various collectors and collections make up the museums holdings including (but not limited to) those of Octavius Pickard-Cambridge, George Henry Verrall, Pierre François Marie Auguste Dejean, Pierre André Latreille, Alfred Russel Wallace, Charles Darwin, Jacques Marie Frangile Bigot, and Pierre Justin Marie Macquart among others.

See also

- The Abbot's Kitchen, an early chemistry laboratory next to the museum, built at the same time.

- Radcliffe Science Library, the science library of Oxford University, close to the museum.

References

- ↑ Yanni, Carla. Nature's Museums: Victorian Science and the Architecture of Display, Chapter two, passim.

- ↑ Taunton, Larry (26 December 2012). "The atheist who tried to steal Christmas". USA Today. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ↑ Yanni, chapter two, passim

- ↑ Acland, Henry W., M.D. The Oxford Museum. London: George Allen, 1893.

- ↑ Account of the 1860 debate, American Scientist.

- ↑ Ian Hesketh (3 October 2009). Of Apes and Ancestors: Evolution, Christianity, and the Oxford Debate. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-9284-7. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ↑ Charles Darwin (15 December 2009). The Power of Movement in Plants. MobileReference. pp. 549–. ISBN 978-1-60501-636-8. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ↑ J.R. Lucas, Wilberforce and Huxley: A Legendary Encounter http://users.ox.ac.uk/~jrlucas/legend.html retrieved 5 October 2007

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Oxford University Museum of Natural History. |

- Oxford University Museum website

- Regulations for the Oxford University Museum of Natural History

- Virtual Tour of the Oxford University Museum of Natural History

- History of the Insect collections

- Oxford University Estates Services Conservation Management Plan for the University Museum (38mbs)

- Virtual Tour of the Oxford University Museum of Natural History 2014