Arapaima

| Arapaimas | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Osteoglossiformes |

| Family: | Arapaimidae |

| Genus: | Arapaima J. P. Müller, 1843 |

| Type species | |

| Sudis gigas Schinz, 1822 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

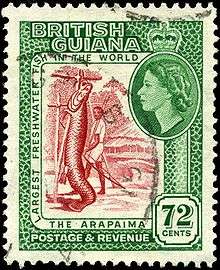

The arapaima, pirarucu, or paiche are any large species of bonytongue in the genus Arapaima native to the Amazon and Essequibo basins of South America. Genus Arapaima is the type genus of the family Arapaimidae.[1][2] They are among the world's largest freshwater fish, reaching as much as 3 m (9.8 ft).[1] They are an important food fish. They have declined in the native range due to overfishing and habitat loss. In contrast, arapaima have been introduced to several tropical regions outside the native range (within South America and elsewhere) where they are sometimes considered invasive species.[3] Its local name, pirarucu, derives from the indigenous words for "pira" meaning "fish" and "urucum" meaning "red".

Arapaima was traditionally regarded as a monotypic genus, but later several species were distinguished.[2][4][5] As a consequence of this taxonomic confusion, most earlier studies were done using the name A. gigas, but this species is only known from old museum specimens and the exact native range is unclear. The regularly seen and studied species is A. arapaima,[4][5][6] although a small number of A. leptosoma also have been recorded in the aquarium trade.[7] The remaining species are virtually unknown: A. agassizii from old detailed drawings (the type specimen itself was lost during World War II bombings) and A. mapae from the type specimen.[2][4][5] A. arapaima is relatively thickset compared to the remaining species.[4][5]

Taxonomy

FishBase recognizes four species in the genus.[1] In addition to these, evidence suggests that a fifth species, A. arapaima should be recognized (this being the widespread, well-known species, otherwise included in A. gigas).[4][5][6][8]

- Arapaima arapaima Valenciennes, 1847

- Arapaima agassizii Valenciennes, 1847

- Arapaima gigas Schinz, 1822

- Arapaima leptosoma D. J. Stewart, 2013

- Arapaima mapae Valenciennes, 1847

These fish are widely dispersed and do not migrate, which leads scientists to suppose that more species are waiting to be discovered among the depths of the Amazon Basin harbors. Sites such as these offer the likelihood of diversity.[9]

Morphology

Arapaima can reach lengths of more than 2 m (6 ft 7 in), in some exceptional cases even more than 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) and over 100 kg (220 lb). The maximum recorded weight for the species is 200 kg (440 lb), while the longest recorded length was 4.52 m (15 ft). As a result of overfishing, large arapaima of more than 2 m (6 ft 7 in) are seldom found in the wild.

The arapaima is torpedo-shaped with large blackish-green scales and red markings. It is streamlined and sleek, with its dorsal and anal fin set near its tail.

Arapaima scales have a mineralised, hard, outer layer with a corrugated surface under which lie several layers of collagen fibres in a Bouligand-type arrangment.[10][11] In a structure similar to plywood, the fibres in each successive layer are oriented at large angles to those in the previous layer, increasing toughness. The hard, corrugated surface of the outer layer, and the tough internal collagen layers work synergistically to contribute to their ability to flex and deform while providing strength and protection—a solution that allows the fish to remain mobile while heavily armored.[12] The arapaima has a fundamental dependence on surface air to breathe. In addition to gills, it has a modified and enlarged swim bladder, composed of lung-like tissue, which enables it to extract oxygen from the air.[13]

Ecology

The diet of the arapaima consists of fish, crustaceans and small land animals that walk near the shore. The fish is an air-breather, using its labyrinth organ, which is rich in blood vessels and opens into the fish's mouth,[14] an advantage in oxygen-deprived water that is often found in the Amazon River. This fish is able to survive in oxbow lakes with dissolved oxygen as low as 0.5 ppm. In the wetlands of the Araguaia, one of the most important refuges for this species, it is the top predator in such lakes during the low water season, when the lakes are isolated from the rivers and oxygen levels drop, rendering its prey lethargic and vulnerable.

Arapaimas may leap out of the water if they feel constrained by their environment or harassed.

Life history/behavior

Reproduction

Due to its geographic ranges, arapaima's life cycle is greatly affected by seasonal flooding. Various pictures show slightly different coloring owing to colour changes when they reproduce.[15] The arapaima lays its eggs during the months when water levels are low or beginning to rise. They build a nest about 50 centimetres (20 in) wide and 15 centimetres (5.9 in) deep, usually in muddy-bottomed areas. As the water rises, the eggs hatch and the offspring have the flood season during May to August to prosper such that yearly spawning is regulated seasonally.

Brooding

The arapaima male is a mouthbrooder, like his relative, the Osteoglossum, meaning the young are protected in his mouth until they are older. The female arapaima helps to protect the male and the young by circling them and fending off potential predators.

In his book The Whispering Land, naturalist Gerald Durrell reported that in Argentina, female arapaima had been seen secreting a white substance from a gland in the head and that their young were seemingly feeding on the substance.

Evolution

Fossils of arapaima or a very similar species have been found in the Miocene Villavieja Formation of Colombia[16] Museum specimens are found in France, England, United States, Brazil, Guyana, Ecuador and Perú.[17]

Relation to humans

Arapaima is used in many ways by local human populations.

It is considered an aquarium fish, one that requires substantial space and food.

Its tongue is thought to have medicinal qualities in South America. It is dried and combined with guarana bark, which is grated and mixed into water. Doses are given to kill intestinal worms.

The bony tongue is used to scrape cylinders of dried guarana, an ingredient in some beverages, and the bony scales are used as nail files.

Arapaima produces boneless steaks and is considered a delicacy. In the Amazon region locals often salt and dry the meat, rolling it into a cigar-style package that is then tied and can be stored without rotting, which is important in a region with little refrigeration. Arapaimas are referred to as the "cod of the Amazon", and can be prepared in the same way as traditional salted cod.

In July 2009, villagers around Kenyir Lake in Terengganu, Malaysia, reported sighting A. gigas. The "Kenyir monster", or "dragon fish" as the locals call it, was claimed to be responsible for the mysterious drowning of two men on 17 June.[18]

Fishing

Fishing is allowed only in certain remote areas of the Amazon basin, and must either be catch-and-release or subsistence harvesting by native peoples.

Some 7000 tons per year were taken from 1918 to 1924, the height of its commercial fishing. Demand led to farming of the fish by the ribeirinhos (people living on riverbanks).[19]

They are harpooned or caught in large nets. Since the arapaima needs to surface to breathe air, traditional arapaima fishermen harpoon them and then club them to death. An individual fish can yield as much as 70 kilograms (150 lb) of meat.

The arapaima was introduced for fishing in Thailand and Malaysia. Fishing in Thailand can be done in several lakes, where specimens over 150 kilograms (330 lb) are often landed and then released.

With catch-and-release after the fish is landed, it must be held for five minutes until it takes a breath. The fish has a large blood vessel running down its spine and lifting the fish clear of the water for trophy shots can rupture this vessel, causing death.

Aquaculture

In 2013 Whole Foods began selling farm-raised arapaima in the United States as a cheaper alternative to halibut or Chilean sea bass.[20]

Status

Conservation

The status of the arapaima population in the Amazon River Basin is unknown, hence it is listed on the IUCN red list as Data Deficient. It is difficult to conduct a population census in so large an area, and it is problematic to monitor catches in a trade that is largely illegal. Commercial arapaima fishing is banned by the Brazilian government due to its commercial extinction. Colombia bans the fishing and consumption of the Arapaima between October 1 and March 15 as it's within the seasons that the fish breeds.[21]

Threats

A 2014 study found that the fish was depleted or overexploited at 93% of the sites examined and well-managed or unfished in only 7%; the fish appeared to be extirpated in 19% of these sites.[22][23] Arapaima are particularly vulnerable to overfishing because of their size and because they must surface periodically to breathe.

Gallery

-

Arapaima at the Shedd Aquarium

-

Arapaima at the Manila Ocean Park

-

Arapaima at the Cologne Zoological Garden

-

Arapaima leptosoma at the zoo (sea aquarium) in Sevastopol

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2013). Species of Arapaima in FishBase. August 2013 version.

- 1 2 3 Castello, L.; and Stewart, D.J (2008). Assessing CITES non-detriment findings procedures for Arapaima in Brazil. NDF Workshop case studies (Mexico 2008), WG 8 – Fishes, Case study 1

- ↑ Miranda-Chumacero, G.; Wallace, R.; Calderón, H.; Calderón, G.; Willink, P.; Guerrero, M.; Siles, T.M.; Lara, K.; and Chuqui, D. (2012). Distribution of arapaima (Arapaima gigas) (Pisces: Arapaimatidae) in Bolivia: implications in the control and management of a non-native population. BioInvasions Records 1(2): 129–138

- 1 2 3 4 5 Stewart, D.J. (2013). A New Species of Arapaima (Osteoglossomorpha: Osteoglossidae) from the Solimões River, Amazonas State, Brazil. Copeia, 2013 (3): 470-476.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Stewart, D. J. (2013). Re-description of Arapaima agassizii (Valenciennes), a rare fish from Brazil (Osteoglossomorpha, Osteoglossidae). Copeia, 2013: 38-51

- 1 2 Dawes, J: Arapaima Re-classification and the Trade. Archived December 22, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 24 May 2014

- ↑ Howard, B.C. (13 October 2013). New Species of Giant Air-Breathing Fish: Freshwater Species of the Week. National Geographic. Retrieved 24 May 2014

- ↑ Clarke, M. (15 January 2010).Five Arapaima species, not one. Practicalfishkeeping. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ Arantes, Caroline C., Leandro Castello, Mauricio Cetra, and Ana Schilling. "Environmental Influences on the Distribution of Arapaima in Amazon Floodplains." Environmental Biology of Fishes (2011): 1257-267. Print.

- ↑ Sherman, Vincent R. (2016). "A comparative study of piscine defense: The scales of Arapaima gigas, Latimeria chalumnae and Atractosteus spatula". Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials. doi:10.1016/j.jmbbm.2016.10.001.

- ↑ "Engineers Find Inspiration for New Materials in Piranha-proof Armor". Jacobs School of Engineering, UC San Diego. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ↑ Sherman, Vincent R. (2015). "The materials science of collagen". Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials. 52: 22–50. doi:10.1016/j.jmbbm.2015.05.023.

- ↑ "Arapaima videos, photos and facts - Arapaima gigas - ARKive". arkive.org.

- ↑ Ferraris, C.J. (2003). "Family Arapaimatidae". In Reis, R.E.; Kullander, S.O.; Ferraris, C.J. Check List of the Freshwater Fishes of South and Central America. Porto Alegre, Brazil: EDIPUCRS. pp. 582–588.

- ↑ "Fish Warrior: Amazon Giant." http://natgeotv.com/. National Geographic. Web. <http://natgeotv.com/ca/fish-warrior/facts>.

- ↑ Lundberg, J.G. & B. Chernoff (1992). "A Miocene fossil of the Amazonian fish Arapaima (Teleostei, Arapaimidae) from the Magdalena River region of Colombia--Biogeographic and evolutionary implications". Biotropica. 24 (1): 2–14. doi:10.2307/2388468. JSTOR 2388468.

- ↑ Arantes, Caroline C., Leandro Castello, Mauricio Cetra, and Ana Schilling. "Environmental Influences on the Distribution of Arapaima in Amazon Floodplains." Environmental Biology of Fishes (2011): 1257-267. Print.

- ↑ "Archives". thestar.com.my.

- ↑ River Monsters episode name: "Unhooked", Animal Planet, 16 July 2010 10AM PDT.

- ↑ "Saving an Endangered Fish by Eating More of It - BusinessWeek Education Resource Center". resourcecenter.businessweek.com. Retrieved 2015-08-20.

- ↑ http://www.ica.gov.co/getdoc/a7e40c46-1243-45a9-80d4-c52097320b2b/vedas.aspx

- ↑ Castello, L.; Arantes, C. C.; Mcgrath, D. G.; Stewart, D. J.; De Sousa, F. S. (2014-08-13). "Understanding fishing-induced extinctions in the Amazon". Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems. doi:10.1002/aqc.2491.

- ↑ Gough, Z. (2014-08-13). "Giant Amazon fish 'locally extinct' due to overfishing". BC Nature. BBC. Archived from the original on 2014-08-14. Retrieved 2014-08-15. External link in

|work=(help)

Bibliography

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2009). "Arapaima gigas" in FishBase. 01 2009 version.

- Gourmet Magazine (May 2007 Volume LXVII No. 5) Article: "The Quarter Ton Fish" pg. 106; Condé Nast Publications

- National Geographic News "Search Is on for World's Biggest Freshwater Fish"