Treaty of Paris (1763)

|

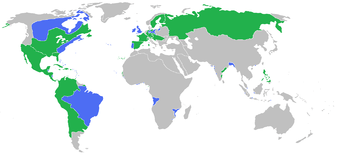

The combatants of the Seven Years' War as shown before the outbreak of war in the mid-1750s.

Great Britain, Prussia, Portugal, with allies

France, Spain, Austria, Russia, with allies | |

| Context | End of the Seven Years' War (known as the French and Indian War in North America) |

|---|---|

| Signed | 10 February 1763 |

| Location |

|

| Negotiators | |

| Signatories | |

| Parties | |

|

| |

| See also: Treaty of Hubertusburg (1763), Treaty of Paris (1783). | |

The Treaty of Paris, also known as the Treaty of 1763, was signed on 10 February 1763 by the kingdoms of Great Britain, France and Spain, with Portugal in agreement, after Great Britain's victory over France and Spain during the Seven Years' War.

The signing of the treaty formally ended the Seven Years' War, known as the French and Indian War in the North American theatre,[1] and marked the beginning of an era of British dominance outside Europe.[2] Great Britain and France each returned much of the territory that they had captured during the war, but Great Britain gained much of France's possessions in North America. Additionally, Great Britain agreed to protect Roman Catholicism in the New World. The treaty did not involve Prussia and Austria as they signed a separate agreement, the Treaty of Hubertusburg, five days later.

Exchange of territories

During the war, Great Britain had conquered the French colonies of Canada, Guadeloupe, Saint Lucia, Dominica, Grenada, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Tobago, the French "factories" (trading posts) in India, the slave-trading station at Gorée, the Sénégal River and its settlements, and the Spanish colonies of Manila (in the Philippines) and Havana (in Cuba). France had captured Minorca and British trading posts in Sumatra, while Spain had captured the border fortress of Almeida in Portugal, and Colonia del Sacramento in South America.

In the treaty, most of these territories were restored to their original owners, but not all: Britain made considerable gains.[3] France and Spain restored all their conquests to Britain and Portugal. Britain restored Manila and Havana to Spain, and Guadeloupe, Martinique, Saint Lucia, Gorée, and the Indian factories to France.[4] In return, France ceded Canada, Dominica, Grenada, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Tobago to Britain. France also ceded the eastern half of French Louisiana to Britain; that is, the area from the Mississippi River to the Appalachian Mountains.[5]

Spain ceded Florida to Britain.[4] France had already secretly given Louisiana to Spain in the Treaty of Fontainebleau (1762). In addition, while France regained its factories in India, France recognized British clients as the rulers of key Indian native states, and pledged not to send troops to Bengal. Britain agreed to demolish its fortifications in British Honduras (now Belize), but retained a logwood-cutting colony there. Britain confirmed the right of its new subjects to practice Catholicism.[6]

France ceded all of its territory in mainland North America, but retained fishing rights off Newfoundland and the two small islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon, where its fishermen could dry their catch. In turn France gained the return of its sugar colony, Guadeloupe, which it considered more valuable than Canada.[7] Voltaire had notoriously dismissed Canada as "Quelques arpents de neige", "A few acres of snow".[8]

Louisiana question

The Treaty of Paris is frequently noted as the point at which France gave Louisiana to Spain. The transfer, however, occurred with the Treaty of Fontainebleau (1762) but was not publicly announced until 1764. The Treaty of Paris was to give Britain the east side of the Mississippi (including Baton Rouge, Louisiana, which was to be part of the British territory of West Florida). New Orleans on the east side remained in French hands (albeit temporarily). The Mississippi River corridor in what is modern day Louisiana was to be reunited following the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 and the Adams–Onís Treaty in 1819.

The 1763 treaty states in Article VII:

VII. French territories on the continent of America; it is agreed, that, for the future, the confines between the dominions of his Britannick Majesty and those of his Most Christian Majesty, in that part of the world, shall be fixed irrevocably by a line drawn along the middle of the River Mississippi, from its source to the river Iberville, and from thence, by a line drawn along the middle of this river, and the lakes Maurepas and Pontchartrain to the sea; and for this purpose, the Most Christian King cedes in full right, and guaranties to his Britannick Majesty the river and port of the Mobile, and everything which he possesses, or ought to possess, on the left side of the river Mississippi, except the town of New Orleans and the island in which it is situated, which shall remain to France, provided that the navigation of the river Mississippi shall be equally free, as well to the subjects of Great Britain as to those of France, in its whole breadth and length, from its source to the sea, and expressly that part which is between the said island of New Orleans and the right bank of that river, as well as the passage both in and out of its mouth: It is farther stipulated, that the vessels belonging to the subjects of either nation shall not be stopped, visited, or subjected to the payment of any duty whatsoever. The stipulations inserted in the IVth article, in favour of the inhabitants of Canada shall also take place with regard to the inhabitants of the countries ceded by this article.

Canada question

British perspective

While the war was fought all over the world, the British began the war over French possessions in North America.[9] After a long debate of the relative merits of Guadeloupe, which produced £6 million a year in sugar, versus Canada which was expensive to keep, Great Britain decided to keep Canada for strategic reasons and return Guadeloupe to France.[10] While the war had weakened France, it was still a European power. British Prime Minister Lord Bute wanted a peace that would not aggravate France towards a second war.[11] This explains why Great Britain agreed to return so much while being in such a strong position.

Though the Protestant British feared Roman Catholics, Great Britain did not want to antagonize France through expulsion or forced conversion. Also, it did not want French settlers to leave Canada to strengthen other French settlements in North America.[12] This explains Great Britain's willingness to protect Roman Catholics living in Canada.

French perspective

Unlike Lord Bute, the French Foreign Minister the Duke of Choiseul expected a return to war. However, France needed peace to rebuild.[13] French diplomats believed that without France to keep the Americans in check, the colonists might attempt to revolt. In Canada, France wanted open emigration for those, such as nobility, who would not swear allegiance to the British Crown.[14] Lastly, France required protection for Roman Catholics in North America considering Britain's previous treatment of Roman Catholics under its jurisdiction.

Canada in the Treaty of Paris

The article states:

IV. His Most Christian Majesty renounces all pretensions which he has heretofore formed or might have formed to Nova Scotia or Acadia in all its parts, and guaranties the whole of it, and with all its dependencies, to the King of Great Britain: Moreover, his Most Christian Majesty cedes and guaranties to his said Britannick Majesty, in full right, Canada, with all its dependencies, as well as the island of Cape Breton, and all the other islands and coasts in the gulph and river of St. Lawrence, and in general, every thing that depends on the said countries, lands, islands, and coasts, with the sovereignty, property, possession, and all rights acquired by treaty, or otherwise, which the Most Christian King and the Crown of France have had till now over the said countries, lands, islands, places, coasts, and their inhabitants, so that the Most Christian King cedes and makes over the whole to the said King, and to the Crown of Great Britain, and that in the most ample manner and form, without restriction, and without any liberty to depart from the said cession and guaranty under any pretence, or to disturb Great Britain in the possessions above mentioned. His Britannick Majesty, on his side, agrees to grant the liberty of the Catholick religion to the inhabitants of Canada: he will, in consequence, give the most precise and most effectual orders, that his new Roman Catholic subjects may profess the worship of their religion according to the rites of the Romish church, as far as the laws of Great Britain permit. His Britannick Majesty farther agrees, that the French inhabitants, or others who had been subjects of the Most Christian King in Canada, may retire with all safety and freedom wherever they shall think proper, and may sell their estates, provided it be to the subjects of his Britannick Majesty, and bring away their effects as well as their persons, without being restrained in their emigration, under any pretence whatsoever, except that of debts or of criminal prosecutions: The term limited for this emigration shall be fixed to the space of eighteen months, to be computed from the day of the exchange of the ratification of the present treaty.

Dunkirk question

During the negotiations that led to the treaty, a major issue of dispute between Britain and France had been over the status of the fortifications of the French coastal settlement of Dunkirk. The British had long feared that it would be used as a staging post to launch a French invasion of Britain. Under the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 they had forced France to concede extreme limits on the fortifications there. The 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle had allowed more generous terms,[15] and France had constructed greater defences for the town.

By the Treaty Britain forced France to accept the earlier 1713 conditions and demolish the fortifications they had constructed since then.[16] This would be a continuing source of resentment to France, who would eventually have this clause overturned in the 1783 Treaty of Paris which brought an end to the American Revolutionary War.

Reaction

When Lord Bute became Prime Minister in 1762, he pushed for a resolution to the war with France and Spain, fearing that Great Britain could not govern all of its newly acquired territories. In what Winston Churchill would later term a policy of "appeasement," Bute returned some colonies to Spain and France in the negotiations.[17] Despite a desire for peace, many in the British parliament opposed the return of any gains made during the war. Notable among the opposition was former Prime Minister William Pitt, the Elder, who warned that the terms of the treaty would only lead to further conflicts once France and Spain had time to rebuild. "The peace was insecure," he would later say, "because it restored the enemy to her former greatness. The peace was inadequate, because the places gained were no equivalent for the places surrendered."[18] The treaty passed 319 votes to 65 opposed.[19]

The Treaty of Paris took no consideration of Great Britain's battered continental ally, Frederick II of Prussia. Frederick would have to negotiate peace terms separately in the Treaty of Hubertusburg. For decades following the Seven Years' War, Frederick II would consider the Treaty of Paris as a British betrayal.

The American colonists were disappointed by the protection of Roman Catholicism in the Treaty of Paris because of their own strong Protestant faith.[20] Some have pointed to this as one reason for the breakdown of American–British relations.[20]

Effects on French Canada

The article provided for unrestrained emigration for 18 months from Canada. However, passage of British ships was expensive.[14] A total of 1,600 people left New France through the Treaty clause, but only 270 French Canadians.[14] Some have claimed that this was part of British policy to limit emigration.[14]

Article IV of the treaty allowed Roman Catholicism to be practised in Canada.[21] George III agreed to allow Catholicism within the laws of Great Britain. In this period, British laws included various Test Acts to prevent governmental, judicial, and bureaucratic appointments from going to Roman Catholics. Roman Catholics were believed to be agents of the Jacobite Pretenders to the throne, who normally resided in France supported by the French regime.[22] This was relaxed in Quebec to some degree, but top positions like governorships were still held by Anglicans.[21]

Article IV has also been cited as the basis for Quebec often having its unique set of laws that are different from the rest of Canada. There was a general constitutional principle in the United Kingdom to allow colonies taken through conquest to continue their own laws.[23] This was limited by royal prerogative, and the monarch could still choose to change the accepted laws in a conquered colony.[23] However, the treaty eliminated this power because by a different constitutional principle, terms of a treaty were considered paramount.[23] In practice, Roman Catholics could become jurors in inferior courts in Quebec and argue based on principles of French law.[24] However, the judge was British and his opinion on French law could be limited or hostile.[24] If the case was appealed to a superior court, neither French law nor Roman Catholic jurors were allowed.[25]

Many French residents of what are now Canada's Maritime provinces, called Acadians, were deported during the Great Expulsion (1755–63). After the signing of the peace treaty guaranteed some rights to Roman Catholics, some Acadians returned to Canada. However, they were no longer welcome in English Nova Scotia.[26] They were forced into New Brunswick, which is a bilingual province today as a result of that relocation.[27]

Much land previously owned by France was now owned by Britain, and the French people of Quebec felt great betrayal at the French concession. Commander-in-Chief of the British Jeffrey Amherst noted that, "Many of the Canadians consider their Colony to be of utmost consequence to France & cannot be convinced … that their Country has been conceded to Great Britain".[28]

See also

References

- ↑ Marston, Daniel (2002). The French–Indian War 1754–1760. Osprey Publishing. p. 84. ISBN 0-415-96838-0.

- ↑ "Wars and Battles: Treaty of Paris (1763)". www.u-s-history.com.

In a nutshell, Britain emerged as the world's leading colonial empire.

- ↑ "The Treaty of Paris ends the French and Indian War". www.thenagain.info.

- 1 2 "The Present State of the West-Indies: Containing an Accurate Description of What Parts Are Possessed by the Several Powers in Europe". World Digital Library. 1778. Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- ↑ "His Most Christian Majesty cedes and guaranties to his said Britannick Majesty, in full right, Canada, with all its dependencies, as well as the island of Cape Breton, and all the other islands and coasts in the gulph and river of St. Lawrence, and in general, every thing that depends on the said countries, lands, islands, and coasts, with the sovereignty, property, possession, and all rights acquired by treaty, or otherwise, which the Most Christian King and the Crown of France have had till now over the said countries, lands, islands, places, coasts, and their inhabitants" — Article IV of the

Treaty of Paris (1763) at Wikisource

Treaty of Paris (1763) at Wikisource - ↑ Extracts from the Treaty of Paris of 1763. A. Lovell & Co. 1892. p. 6.

His Britannick Majesty, on his side, agrees to grant the liberty of the Roman Catholic religion to the inhabitants of Canada.

- ↑ Dewar, Helen (December 2010). "Canada or Guadeloupe?: French and British Perceptions of Empire, 1760–1783". Canadian Historical Review. 91 (4): 637–660. doi:10.3138/chr.91.4.637.

- ↑ "Quelques arpents de neige".

- ↑ Monod p 197–98

- ↑ Colin G. Calloway (2006). The Scratch of a Pen: 1763 and the Transformation of North America. Oxford U.P. p. 8.

- ↑ Gough p 95

- ↑ Calloway p 113–14

- ↑ Rashed, Zenab Esmat (1951). The Peace of Paris. Liverpool University Press. p. 209. ISBN 978-0853-23202-5.

- 1 2 3 4 Calloway p 114

- ↑ Dull p.5

- ↑ Dull p.194–243

- ↑ Winston Churchill (reprint 2001). The Great Republic: A History of America. Modern Library. p. 52. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Simms, Brendan (2007). Three Victories and a Defeat: The Rise and Fall of the First British Empire, 1714–1783. Allan Lane. p. 496. ISBN 978-0713-99426-1.

- ↑ Fowler, William M. (2004). Empires at War: the French and Indian War and the struggle for North America, 1754–1763. Walker & Company. p. 271. ISBN 978-0802-71411-4.

- 1 2 Monod p 201

- 1 2 Conklin p 34

- ↑ Colley, Linda (1992). Britons: Forging the Nation 1707–1837. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-300-15280-7.

- 1 2 3 Conklin p 35

- 1 2 Calloway p 120

- ↑ Calloway p 121

- ↑ Price, p 136

- ↑ Price p 136–137

- ↑ Calloway p 113

Further reading

- Calloway, Colin Gordon (2006). The scratch of a pen: 1763 and the transformation of North America. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Churchill, Sir Winston (1956). The Great Republic: A History of America. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-375-50320-X.

- Conklin, William E. (1979). In Defence of Fundamental Rights. Springer.

- Dull, Jonathan R. (2005). The French Navy and the Seven Years' War. University of Nebraska.

- Gough, Barry M. (1992). British Mercantile Interests in the Making of the Peace of Paris, 1763. Edwin Meller Press.

- Monod, Paul Kleber (2009). Imperial Island: A History of Britain and Its Empire, 1660–1837. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Price, Joseph Edward (2007). The status of French among youth in a bilingual American–Canadian border community: the case of Madawaska, Maine. Indiana University.

External links

- Treaty of Paris Profile and Videos - Chickasaw.TV

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- The Treaty of Paris and its Consequences (French)

- Entry on the Treaty of Paris from The Canadian Encyclopedia

- Treaty of Paris at the Avalon Project of the Yale Law School