Phonograph cylinder

Phonograph cylinders are the earliest commercial medium for recording and reproducing sound. Commonly known simply as "records" in their era of greatest popularity (c. 1896–1915), these hollow cylindrical objects have an audio recording engraved on the outside surface, which can be reproduced when they are played on a mechanical cylinder phonograph. In the 1910s, the competing disc record system triumphed in the marketplace to become the dominant commercial audio medium.

Early development

Two Edison cylinder records (left and right) and their cylindrical cardboard boxes (center) |

Brown wax cylinders showing various shades (and mold damage) |

| Paper record slip from 1903 cylinder |

| Back side of 1903 record slip |

Portion of the label from the outside of a Columbia cylinder box, before 1901. Note that the title is hand-written. |

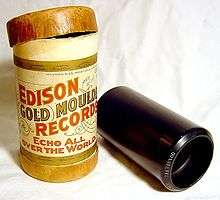

Edison Gold Moulded record made of relatively hard black wax, ca. 1904 |

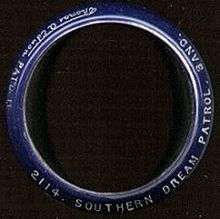

Rim of Edison "Blue Amberol" celluloid cylinder with plaster core |

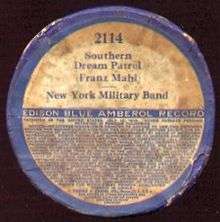

Blue Amberol cylinder box lid |

The phonograph was invented by Thomas Edison and his team on July 18, 1877. His first successful recording and reproduction of intelligible sounds, achieved early in the following December, used a thin sheet of tin foil wrapped around a hand-cranked grooved metal cylinder.[1] Tin foil was not a practical recording medium for either commercial or artistic purposes and the crude hand-cranked phonograph was only marketed as a novelty, to little or no profit. Edison moved on to developing a practical incandescent electric light and the next improvements to sound recording technology were made by others.

Following seven years of research and experimentation at their Volta Laboratory, Charles Sumner Tainter, Alexander Graham Bell and Chichester Bell introduced wax as the recording medium and engraving, rather than indenting, as the recording method. In 1887, their "Graphophone" system, which recorded dictation on disposable cardboard tubes with a thin wax coating, was being put to the test of practical use by official reporters of the US Congress, with commercial units later being produced by the Dictaphone Corporation. After this system was demonstrated to Edison's representatives, Edison quickly resumed work on the phonograph. He settled on a thicker all-wax cylinder, the surface of which could be repeatedly shaved down for reuse. Both the Graphophone and Edison's "Perfected Phonograph" were commercialized in 1888. Eventually, a patent-sharing agreement was signed and the wax-coated cardboard tubes were abandoned in favor of Edison's all-wax cylinders as an interchangeable standard format.[2]

Beginning in 1889, prerecorded wax cylinders were marketed. These have professionally made recordings of songs, instrumental music or humorous monologues in their grooves. At first, the only customers for them were proprietors of nickel-in-the-slot machines—the first juke boxes—installed in arcades and taverns, but within a few years private owners of phonographs were increasingly buying them for home use. Each cylinder can easily be placed on and removed from the mandrel of the machine used to play them. Unlike later, shorter-playing high-speed cylinders, early cylinder recordings were usually cut at a speed of about 120 rpm and can play for as long as three minutes. They were made of a relatively soft wax formulation and would wear out after they were played a few dozen times. The buyer could then use a mechanism which left their surfaces shaved smooth so new recordings could be made on them.

Cylinder machines of the late 1880s and the 1890s were usually sold with recording attachments. The ability to record as well as play back sound was an advantage of cylinder phonographs over the competition from cheaper disc record phonographs which began to be mass-marketed at the end of the 1890s, as the disc system machines can be used only to play back prerecorded sound.

In the earliest stages of phonograph manufacturing various competing incompatible types of cylinder recordings were made. A standard system was decided upon by Edison Records, Columbia Phonograph, and other companies in the late 1880s. The standard cylinders are about 4 inches (10 cm) long, 2¼ inches in diameter, and play about two minutes of music or other sound.

Over the years the type of wax used in cylinders was improved and hardened so that cylinders could be played with good quality over 100 times. In 1902 Edison Records launched a line of improved hard wax cylinders marketed as "Edison Gold Molded Records". The major development of this line of cylinders is that Edison had developed a process that allowed a mold to be made from a master cylinder which then permitted the production of several hundred cylinders to be made from the mold.[3] The impressive mention of gold referred only to the extremely thin gold coating deposited onto the master wax cylinder to make it electrically conductive, the first step in creating the metal mold.

Originally all cylinders sold had to be recorded live on the softer brown wax which wore out in as few as twenty playings. Later cylinders were reproduced either mechanically or by linking phonographs together with rubber tubes.[4] Although not completely satisfactory, the result was almost good enough to be sold.

Commercial packaging

Cylinders were sold in cardboard tubes with cardboard caps on each end, the upper one a removable lid. Like cylindrical containers for hats, they were simply called "boxes", the word still used by experienced collectors. Within these "boxes", or tubes, the earliest soft wax cylinders came swathed in a separate length of thick cotton batting. Later molded hard-wax cylinders were sold in tubes with a cotton lining. Celluloid cylinders were sold in unlined tubes. These protective tubes were normally kept and used to house the cylinders after purchase. Their appearance motivated bandleader John Philip Sousa to deride their contents as "canned music", an epithet he borrowed from Mark Twain,[5] but that did not stop Sousa's band from profiting by recording on cylinders.

The earliest cylinder boxes have a plain brown paper exterior, sometimes rubber-stamped with the company name. By the late 1890s, record companies usually pasted a generic printed label around the outside of the box, sometimes with a penciled catalog number but no other indication of the identity of the recording inside. A slip of paper stating the title and performer was placed inside the box with the cylinder. At first this information was hand-written or typed on each slip, but printed versions became more common once cylinders were sold in large enough quantities to justify the printing set-up cost. The recording itself usually began with a spoken announcement of the title and performer and also the name of the record company. On a typical Edison record slip from 1903, the consumer is invited to cut off a coupon with the printed information and paste it onto the lid of the box. Alternatively, a circular area within the coupon could be cut out and pasted onto the end of a spindle for that cylinder in one of the specially built cases and cabinets made for storing cylinder records. Only a minority of cylinder record customers purchased such storage units, however. Slightly later, the record number was stamped on the lid, then later still a printed label with the title and artist information was factory-applied to the lid. Shortly after the start of the 20th century, an abbreviated version of this information was impressed into or printed on one edge of the cylinder itself.

Hard plastic cylinders

| ||||

In 1900, Thomas B Lambert was granted a patent that described a process for mass-producing cylinders made from celluloid, an early hard plastic (though in fact Henri Lioret of France was producing celluloid cylinders as early as 1893).[6] That same year, the Lambert Company of Chicago began mass marketing cylinder records made of the new material, that would not break if dropped and could be played thousands of times without wearing out, though the choice of the bright pink color of early cylinders may have been a marketing error. The color was changed to black in 1903,[7] though brown and blue cylinders were also produced. The cylinders were colored because the colored dye layer reduced the surface noise. The hard inflexible material could not be shaved and recorded over unlike wax cylinders, but had the advantage of being a nearly permanent record.

Such "indestructible" style cylinders are arguably the most durable form of sound recording produced in the entire era of analog audio before the introduction of digital audio; they can withstand a greater number of playbacks before wearing out than later media such as the vinyl record or audio tape. The celluloid material shrinks with the passing years. A typical Lambert cylinder will have shrunk by approximately 3 millimeters in length in the 100 years or so since their manufacture (the actual amount is very dependent on storage conditions). Thus the grooves will no longer be 100 per inch and the cylinder will skip if played. The diameter will also have shrunk and many cylinders will no longer fit on a phonograph mandrel unless (very carefully) reamed to fit. Such cylinders can still be played quite satisfactorily on suitable modern equipment. The Lambert company was put out of business in 1906 due to repeated actions from Edison for patent infringement (which Lambert had not actually committed - it was the cost of defending the actions that eventually sank Lambert).

This superior technology was licensed by a few companies including the Indestructible Record Company in 1906 and Columbia Phonograph Company in 1908. The Edison-Bell company in Europe had separately licensed the technology and were able to market Edison's titles in both wax (popular series) and celluloid (indestructible series). Lambert was able to license the process because the patent was not owned by the now defunct Lambert Company, but by Lambert himself.

Edison had introduced wax cylinders that played for nominally 4 minutes (instead of the usual 2) in 1909 under the Amberol brand. These were made from a harder (and more easily breakable) form of wax to withstand the smaller stylus used to play them. The longer playing time was achieved by shrinking the groove size and spacing them twice as close together. In 1912, the Edison company eventually acquired Lambert's patents to the celluloid technology, and almost immediately started production under a variation of their existing Amberol brand as Edison Blue Amberol Records.[8] These new celluloid recordings were given a core made from plaster of Paris. The celluloid material itself was blue in color, but purple was introduced in 1919, "... for more sophisticated selections". The use of the plaster core provided resistance to the shrinkage of the celluloid, but the playing surface is still liable to split if stored in less than ideal conditions. The plaster core itself can deteriorate in conditions that are too damp or too dry. Nevertheless, most Blue Amberol cylinders are, today, quite playable on antique phonographs or modern equipment alike (though the plaster core may need some reaming).

Edison made several designs of phonographs both with internal and external horns for playing these improved cylinder records. The internally horned models were called Amberolas. Edison also marketed its "Fireside" model phonograph with a gearshift and a 'model K' reproducer with two styli that allowed it to play both 2-minute and 4-minute cylinders.[9] Conversion kits were also produced for some of the later model 2 minute phonographs adding a gear change and a second 'model H' reproducer. These kits were also shipped with a set of 12 (wax) Amberol cylinders in distinctive orange boxes. The purchaser had no choice as to the titles.

Disc records

In the era before World War I, phonograph cylinders and disc records competed with each other for public favor.

The audio fidelity of a sound groove is debatably better if it is engraved on a cylinder due to better linear tracking. This was not resolved until the advent of RIAA standards in the early 1940s—by which time it had already been rendered academic, as cylinder production stopped with Edison's last efforts in October 1929.

Advantages of cylinders

The cylinder system had certain advantages. As noted, wax cylinders could be used for home recordings, and "indestructible" types could be played over and over many more times than the disc. Cylinders usually rotated twice as fast as contemporary discs, but the linear velocity was comparable to the innermost grooves of the disc. In theory, this would provide generally poorer audio fidelity. Furthermore, since constant angular velocity translates into constant linear velocity (the radius of the helical track is constant), cylinders were also free from inner groove problems suffered by disc recordings. Around 1900, cylinders were, on average, indeed of notably higher audio quality than contemporary discs, but as disc makers improved their technology by 1910 the fidelity differences between better discs and cylinders became minimal.

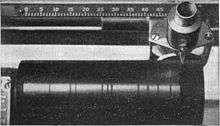

Cylinder phonographs generally used a worm gear to move the stylus in synchronization with the grooves of the recording, whereas most disc machines relied on the grooves to pull the stylus along. This resulted in cylinder records played a number of times having less degradation than discs, but this added mechanism made cylinder machines more expensive.

Advantages of discs

Both the disc records, and the machines to play them, were cheaper to mass-produce than the products of the cylinder system. Disc records were also easier and cheaper to store in bulk, as they could be stacked, or when in paper sleeves put in rows on shelves like books—packed together more densely than cylinder recordings.

Many cylinder phonographs used a belt to turn the mandrel; slight slippage of this belt could make the mandrel turn unevenly, thus resulting in pitch fluctuations. Disc phonographs using a direct system of gears turned more evenly; the heavy metal turntable of disc machines acted as a flywheel, helping to minimize speed wobble.

Virtually all US disc records were single-sided until 1908, when Columbia Records began mass production of discs with recordings pressed on both sides. Except for premium-priced classical records, that quickly became the industry standard. With their capacity effectively doubled, the storage efficiency advantage of discs over the space-wasting cylinder format became even more obvious.

The disc companies had superior advertising and promotion, most notably the Victor Talking Machine Company in the United States and the Gramophone Company/HMV in the Commonwealth. Great singers like Enrico Caruso were hired to record exclusively, helping put the idea in the public mind that that company's product was superior. Edison tried to get into the disc market with hill-and-dale discs, Edison Disc Records.

Decline

Cylinder records continued to compete with the growing disc record market into the 1910s, when discs won the commercial battle. In 1912, Columbia Records, which had been selling both discs and cylinders, dropped the cylinder format, while Edison introduced his unique Diamond Disc format. Beginning in 1915, new Edison cylinder issues were simply dubs of Edison discs and therefore had lower audio quality than the disc originals. Although his cylinders sold in ever-dwindling and eventually tiny quantities, Edison continued to support owners of cylinder phonographs by making new titles available in that format as late as mid-1929.

Later applications

Cylinder phonograph technology continued to be used for Dictaphone and Ediphone recordings for office use for decades.

In 1947, Dictaphone replaced wax cylinders with their Dictabelt technology, which cut a mechanical groove into a plastic belt instead of into a wax cylinder. This was later replaced by magnetic tape recording. However, cylinders for older style dictating machines continued to be available for some years, and it was not unusual to encounter cylinder dictating machines into the 1950s.

In the late 20th and early 21st century some new recordings have been made on cylinders for the novelty effect of using obsolete technology. Probably the most famous of these are by They Might Be Giants, who in 1996 recorded "I Can Hear You" and three other songs, performed without electricity, on an 1898 Edison wax recording studio phonograph at the Edison National Historic Site in West Orange, New Jersey. This song was released on Factory Showroom in 1996 and re-released on the 2002 compilation Dial-A-Song: 20 Years of They Might Be Giants. The other songs recorded were "James K. Polk," "Maybe I Know," and "The Edison Museum," a song about the site of the recording. These recordings were officially released online as MP3 files in 2001.

Small numbers of cylinders have been manufactured in the 21st century out of modern long-lasting materials. Two companies engaged in such enterprise are the Vulcan Cylinder Record Company of Sheffield, England[10] and the Wizard Cylinder Records Company in Baldwin, New York.[11] Both appear to have started in 2002.

In 2010 the British steampunk band The Men That Will Not Be Blamed For Nothing released the track "Sewer", from their debut album, Now That's What I Call Steampunk! Volume 1 on very limited edition Wax Cylinder, only 40 were made and only 30 were put on sale. The box set came with instructions on how to make your own cylinder player for less than £20. The BBC covered the release on Television on BBC Click, on BBC Online and on Radio 5 Live.[12]

In August 2010, Ash International and PARC released the first commercially available glow in the dark phonograph cylinder, which is a work by Michael Esposito and Carl Michael von Hausswolff, entitled "The Ghosts Of Effingham". The cylinder was released in a limited edition of 150 copies, produced by Vulcan Records, Sheffield England.

Preservation of cylinder recordings

Because of the nature of the recording medium, playback of many cylinders can cause degradation of the recording. The replay of cylinders diminishes their fidelity and degrades their recorded signals. Additionally, when exposed to humidity, mold can penetrate cylinders' surface and cause the recordings to have surface noise. Currently, the only professional machine manufactured for the playback of cylinder recordings is the Archéophone player, designed by Henri Chamoux. The Archéophone is used by the Edison National Historic Site, Bowling Green State University (Bowling Green, Ohio), The Department of Special Collections, Donald C Davidson Library at The University of California, Santa Barbara, and many other libraries and archives.

Other modern so-called 'plug-in' mounts, each incorporating the use of a Stanton 500AL MK II magnetic cartridge, have been manufactured from time to time. Information on each may be viewed on the Phonograph Makers Pages link. It is possible to use these on the Edison cylinder players.

Also of interest is the cylinder player built by BBC engineers working in "Engineering Operations - Radio" in 1987. This was equipped with a linear-tracking arm borrowed from a contemporary Revox turntable, and a variety of re-tipped Shure SC35 cartridges.

| ||||

In an attempt to preserve the historic content of the recordings, cylinders can be read with a confocal microscope and converted to a digital audio format. The resulting sound clip in most cases sounds better than stylus playback from the original cylinder. Having an electronic version of the original recordings enables archivists to open access to the recordings to a wider audience. This technique also has the potential to allow for reconstruction of damaged or broken cylinders. (Fadeyev & Haber, 2003)

Modern reproductions of cylinder and disc recordings usually give the impression that the introduction of discs was a quantum leap in audio fidelity, but this is on modern playback equipment; played on equipment from around 1900, the cylinders do not have noticeably more rumble and poorer bass reproduction than the discs. Another factor is that many cylinders are amateur recordings, while disc recording equipment was simply too expensive for anyone but professional engineers; many extremely poor recordings were made on cylinder, while the vast majority of disc recordings were competently recorded. All cylinder recordings were acoustically recorded as were early disc recordings. From the mid-1920s onwards, discs started to be recorded electrically which provided a much enhanced frequency range of recording.

Also important is the quality of the material: the earliest tinfoil recordings wore out fast. Once the tinfoil was removed from the cylinder it was nearly impossible to re-align in playable condition. None of the earliest tinfoil recordings has been played back since the 19th century. (Hypothetically in the future some sound might be salvaged from few surviving flattened out early tinfoil recordings.) The earliest soft wax recordings also wore out quite fast, though they have better fidelity than the early rubber discs.

| ||||

In addition to poor states of preservation, the poor impression modern listeners may get of wax cylinders is from their early date, which can compare unfavorably to recordings made even a dozen years later. Other than a single playable example from 1878 (from an experimental phonograph-clock), the oldest playable preserved cylinders are from the year 1888. These include a severely degraded recording of Johannes Brahms, Handel's Israel in Egypt and a short speech by Sir Arthur Sullivan in fairly listenable condition. Somewhat later are the almost unlistenable 1889 amateur recordings of Nina Grieg. The problem with the wax cylinders is that they readily support the growth of mildew which penetrates throughout the cylinder and, if serious enough, renders the recording unplayable. The earliest preserved rubber disc recordings are children's records, featuring animal noises and nursery rhymes. This means that the earliest disc recordings most music lovers will hear are shellac discs made after 1900, after more than ten years of development.

Gallery

- Celluloid phonograph cylinders displaying a variety of colors

- Wax phonograph cylinders in a variety of diameters

- Wax phonograph cylinders in a variety of lengths

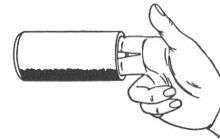

A sound engineer holds one of the Mapleson Cylinders containing a fragment of a live performance recorded at the Metropolitan Opera in 1901

A sound engineer holds one of the Mapleson Cylinders containing a fragment of a live performance recorded at the Metropolitan Opera in 1901 Close-up of the mechanism of an Edison Amberola, manufactured circa 1915

Close-up of the mechanism of an Edison Amberola, manufactured circa 1915 Thomas Edison in 1888 listening to a wax cylinder phonograph at the Edison laboratory, Orange, N.J.

Thomas Edison in 1888 listening to a wax cylinder phonograph at the Edison laboratory, Orange, N.J. Delivering Ediphone wax cylinder recordings of propaganda broadcasts for analysis at the CBS listening post (May 1941)

Delivering Ediphone wax cylinder recordings of propaganda broadcasts for analysis at the CBS listening post (May 1941) Transcribing propaganda broadcasts from Europe recorded on Ediphone cylinders at the CBS listening post (May 1941)

Transcribing propaganda broadcasts from Europe recorded on Ediphone cylinders at the CBS listening post (May 1941)

See also

- Archéophone

- Audio format

- Audio storage

- Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project

- Mapleson Cylinders

- Volta Laboratory and Bureau

References

- Notes

- ↑ "1877 Thomas Edison Cylinder Recorder". Mix Magazine. September 1, 2006. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ↑ Schoenherr, S. (1999) "Charles Sumner Tainter and the Graphophone" (via the Audio Engineering Society). Retrieved 2014-05-04.

- ↑ "The Cylinder Archive - Cylinder Guide: Black Wax Cylinders".

- ↑ "Brown Wax Cylinders".

- ↑ Bierley, Paul Edmund, "The Incredible Band of John Philip Sousa". University of Illinois Press, 2006. p. 82.

- ↑ "Lamberts_EN".

- ↑ http://www.phonographcylinders.com/lambert-replica-cylinder.php

- ↑ "The Cylinder Archive - Cylinder Guide: Amberol and 4-minute Indestructible Cylinders".

- ↑ Model Number taken directly from actual Fireside reproducer.

- ↑ Vulcan Cylinder Record Company (2002). "New phonograph cylinder records". Retrieved 2014-10-20.

- ↑ Peter N. Dilg (Nov–Dec 2008). "The Wizard Cylinder Record Company". Canadian Antique Phonograph Society. Retrieved 2014-10-20.

- ↑ "Tech Know: A journey into sound". BBC News. 2010-05-27.

- ↑ Very Early Recordings, from the Edison National Historic Site, [U.S.] National Park Service.

- Bibliography

- Oliver Read & Walter L. Welch (1976). From Tin Foil to Stereo: Evolution of the Phonograph. Indianapolis, Indiana: Howard W. Sams & Co. Inc. ISBN 978-0672212062.

- George L. Frow & Albert F. Sefl (1978). The Edison Cylinder Phonographs 1877–1929. Sevenoaks, Kent: George F. Frow. ISBN 0-9505462-2-4.

- Fadeyev, V., and C. Haber; Haber; Radding; Maul; McBride; Golden (2003). "Reconstruction of mechanically recorded sound by image processing" (PDF). Journal of the Audio Engineering Society. 51 (December): 172. Bibcode:2001ASAJ..115.2494F.

- Dietrich Schüller (2004). A. Seeger; S. Chaudhuri, eds. "Technology for the Future." In Archives for the Future: Global Perspectives on Audiovisual Archives in the 21st Century. Calcutta, India: Seagull Books.

- David L. Morton Jr. (2004). Sound Recording - The Life Story of a Technology. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Phonograph cylinders. |

- Tinfoil.com — History of phonograph cylinders; listen to many examples dating from 1878 through 1912

- The 1878 Lambert recording - Analysis of the 1878 Frank Lambert recording (until March 2008, believed to be the earliest surviving recording).

- 1888 white wax cylinder - Listen to one of the earliest classical music cylinders ever recorded

- French cylinders - Listen to several French cylinders (Opera, Cafe-Concert)

- "Phonograph cylinders". Archived from the original on 2007-06-21. Retrieved 2003-07-02. on Bill Clark's 78 rpm Record site

- Bob Morritt's Columbia Phonograph Company Cylinder Records Site

- How did they mass produce those old cylinder records?

- The three surviving Edison cylinders on the National Recording Registry with descriptions, audio and transcripts.

- Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project at the University of California, Santa Barbara Library with streaming and downloadable versions of over 10000 cylinders.

- Belfer Cylinders Digital Connection at Syracuse University's Belfer Audio Archive, with streaming and downloadable versions of over 1400 cylinders.

- The Cylinder Archive - Dedicated to the hobby of collecting phonograph cylinder records

- The Archeophone - Official Archeophone site

- Vulcan Cylinder Record Company

- Ethnographic wax cylinders from the British Library

- The City of London Phonograph and Gramophone Society (CLPGS) publishes histories and catalogue lists of many phonograph cylinder manufacturers.