Pikaia

| Pikaia Temporal range: Middle Cambrian | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Subphylum: | Cephalochordata |

| Family: | Pikaiidae Walcott, 1911 |

| Genus: | Pikaia |

| Species: | P. gracilens |

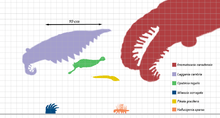

Pikaia gracilens is an extinct cephalochordate animal known from the Middle Cambrian Burgess Shale of British Columbia. Sixteen specimens are known from the Greater Phyllopod bed, where they comprised 0.03% of the community.[1] It resembled the lancelet and perhaps swam much like an eel.

Discovery

P. gracilens was discovered by Charles Walcott and first described by him in 1911. It was named after Pika Peak, a mountain in Alberta, Canada. Based on the obvious and regular segmentation of the body, Walcott classified it as a polychaete worm.

During his re-examination of the Burgess Shale fauna in 1979, paleontologist Simon Conway Morris placed P. gracilens among the chordates, making it perhaps the oldest known ancestor of modern vertebrates. He did this because it seemed to have a very primitive, proto-notochord, however, the status of Pikaia as a chordate is not universally accepted; its preservational mode suggests that it had cuticle, which is uncharacteristic of the vertebrates [2] (although characteristic of other cephalochordates); further, its tentacles are unknown from other vertebrate lineages.[2] The presence of earlier chordates among the Chengjiang, including Haikouichthys and Myllokunmingia, appears to show that cuticle is not necessary for preservation, overruling the taphonomic argument,[3] but the presence of tentacles remains intriguing, and the organism cannot be assigned conclusively, even to the vertebrate stem group. Its anatomy closely resembles the modern creature Branchiostoma.[4]

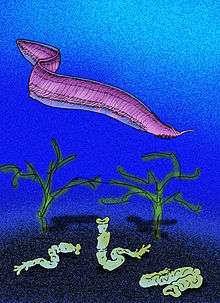

Averaging about 1 1⁄2 inches (3.8 cm) in length, Pikaia swam above the sea floor using its body and an expanded tail fin. Pikaia may have filtered particles from the water as it swam along. Its "tentacles" may be comparable to those in the present-day hagfish, a jawless chordate. Only 60 specimens have been found to date.

Description

Pikaia was a primitive creature that lacked a well defined head, and was typically less than 2 inches (5 centimetres) in length. It swam in the mid-Cambrian seas, and is closely related to the ancestor of all vertebrates, and as such Pikaia gets otherwise-inordinate attention among the multitude of animal fossils found in the famous Burgess Shale in the mountains of British Columbia, Canada.

Until recently, there was no comprehensive account of Pikaia's anatomy. However, Conway Morris and Caron (2012, see further reading) have now published an exhaustive description based on all 114 of the known fossils. They found some new and unexpected characteristics and considered most of these to be primitive features of the first chordate animals. On the basis of these findings, they built a new scenario for chordate evolution. Subsequently, Mallatt and Holland (2013, see further reading) summarized the entire history of Pikaia research, considered Conway Morris and Caron's descriptions, and concluded that many of the newly recognized characters are unique specializations (already divergent in the Cambrian) not helpful for establishing Pikaia as a basal chordate.

When alive, Pikaia was a compressed, leaf-shaped animal. It swam by throwing its body into a series of S-shaped, zigzag curves, similar to the movement of eels. Fish inherited the same swimming movement, but they generally have stiffer backbones. Pikaia had a pair of large head tentacles and a series of short appendages, which may be linked to gill slits, on either side of its head. In these ways, it differs from the living lancelet.

This primitive marine creature shows the essential prerequisites for vertebrates. The flattened body is divided into pairs of segmented muscle blocks, seen as faint vertical lines. The muscles lie on either side of a flexible structure resembling a rod that runs from the tip of the head to the tip of the tail.[5]

Possible ancestor

Much debate on whether Pikaia is a vertebrate ancestor, its worm-like appearance notwithstanding, exists in scientific circles. It looks like a worm that has been flattened sideways. The fossils compressed within the Burgess Shale show chordate features such as traces of an elongate notochord, dorsal nerve cord, and blocks of muscles (myotomes) down either side of the body – all critical features for the evolution of the vertebrates.

The notochord, a flexible rod-like structure that runs along the back of the animal, lengthens and stiffens the body so that it can be flexed from side to side by the muscle blocks for swimming. In the fish and all subsequent vertebrates, the notochord forms the backbone (or vertebral column). The backbone strengthens the body, supports strut-like limbs, and protects the vital dorsal nerve cord, while at the same time allowing the body to bend.

Surprisingly, a Pikaia lookalike still exists today, the lancelet Branchiostoma. This little animal was familiar to biologists long before the Pikaia fossil was discovered. With notochord and paired muscle blocks, the lancelet and Pikaia belong to the chordate group of animals from which the vertebrates have descended. Molecular studies have refuted earlier beliefs that lancelets might be the closest living relative to the vertebrates, and instead favor tunicates in this position.[6] While the lancelet is a chordate, other living and fossil groups, such as acorn worms and graptolite, are more primitive. Called the hemichordates, they have only a notochord-like structure at an early stage of their lives.

The presence of a creature as complex as Pikaia some 530 million years ago reinforces the controversial view that the diversification of life must have extended back well before Cambrian times - perhaps deep into the Precambrian.[5]

Ecology

Pikaia was probably a slow swimmer.[7]

Development of the head

The first sign of head development, cephalization, is seen in chordates such as Pikaia and Branchiostoma. It is thought that development of a head structure resulted from a long body shape, a swimming habit, and a mouth at the end that came into contact with the environment first, as the animal swam forward. The search for food required ways of continually testing what lay ahead so it is thought that anatomical structures for seeing, feeling, and smelling developed around the mouth. The information these structures gathered was processed by a swelling of the nerve cord – the precursor of the brain. Altogether, these front-end structures formed the distinct part of the vertebrate body known as the head.[5]

See also

References

- ↑ "Pikaia gracilens" Burgess Shale Fossil Gallery. Virtual Museum of Canada. 2011.

- 1 2 Butterfield, N. J. (1990), "Organic preservation of non-mineralizing organisms and the taphonomy of the Burgess Shale", Paleobiology, Paleontological Society, 16 (3): 272–286, JSTOR 2400788

- ↑ Conway Morris, S. (2008), "A Redescription of a Rare Chordate, Metaspriggina walcotti Simonetta and Insom, from the Burgess Shale (Middle Cambrian), British Columbia, Canada", Journal of Paleontology, 82 (2): 424–430, doi:10.1666/06-130.1, retrieved 2009-04-28

- ↑ Donoghue, P. C. J.; Purnell, M. A. (2005), "Genome duplication, extinction and vertebrate evolution" (PDF), Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 20 (6): 312–319, doi:10.1016/j.tree.2005.04.008, PMID 16701387

- 1 2 3 Palmer, D., (2000). The Atlas of the Prehistoric World. London: Marshall Publishing Ltd. p66-67.

- ↑ Delsuc et al. (2008): "Additional Molecular Support for the New Chordate Phylogeny". - Genesis, 46(11): 592-604 PDF

- ↑ Lacalli, T. (2012). "The Middle Cambrian fossil Pikaia and the evolution of chordate swimming". EvoDevo. 3 (1): 12. doi:10.1186/2041-9139-3-12. PMC 3390900

. PMID 22695332.

. PMID 22695332.

Further reading

- Bishop, A., Woolley, A. and Hamilton, W. (1999) Minerals, Rocks and Fossils. London: Phillip's

- Lacalli T. (2012) "The Middle Cambrian fossil Pikaia and the evolution of chordate swimming". EvoDevo 3: 12. doi:10.1186/2041-9139-3-12

- Conway Morris, Simon. 1998. The Crucible of Creation: The Burgess Shale and the Rise of Animals. Oxford University Press, New York, New York.

- Gould, Stephen Jay. 1989. Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History. W. W. Norton, New York, NY.

- Norman, D. (1994) Prehistoric Life: the Rise of the Vertebrates, London: Boxtree

- Sheldon, P., Palmer D., Spicer, B. (2001). Fossils and the History of Life. Aberystwyth: Cambrian Printers/The Open University. p. 41-42.

- Conway Morris, S.; Caron, J. B. (2012) "Pikaia gracilens Walcott, a stem-group chordate from the Middle Cambrian of British Columbia". Biological Reviews 87: 480-512.

- Mallatt, J.; Holland, N. D. (2013) "Pikaia gracilens Walcott: stem chordate, or already specialized in the Cambrian?" Journal of Experimental Zoology, Part B, Molecular and Developmental Evolution 320B: 247-271.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pikaia. |

- "Pikaia gracilens". Burgess Shale Fossil Gallery. Virtual Museum of Canada. 2011.

- La evolución de las especies: ¿por qué sobrevivió Pikaia? (Spanish)

- Fossils of the Burgess Shale - Middle Cambrian

- Pikaia gracilens Walcott, a stem-group chordate from the Middle Cambrian of British Columbia