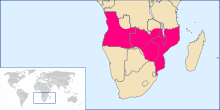

Pink Map

The Pink Map (Portuguese: Mapa cor-de-rosa), also known as the Rose-Coloured Map, was a document prepared in 1885 to represent Portugal's claim of sovereignty over a land corridor connecting their colonies of Angola and Mozambique during the "Scramble for Africa". The area claimed included the whole of what is currently Zimbabwe and large parts of modern Zambia and Malawi.

The British government actively worked to prevent the claim's success; the 1890 British Ultimatum ended the Portuguese hopes, caused serious damage to the prestige of the Portuguese monarchy, and encouraged Republicanism.[1]

Portuguese possessions 1800–1870

At the start of the 19th century, effective Portuguese governance in Africa south of the equator was limited. Portuguese Angola consisted of the areas around Luanda and Benguela, and a few almost independent towns over which Portugal claimed suzerainty, the most northerly of which was Ambriz. Portuguese Mozambique was limited to the Island of Mozambique and several other coastal trading posts or forts as far south as Delagoa Bay.[2] In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Angola's main function was to supply Brazil with slaves. This was facilitated, firstly by the development of coffee plantations in southern Brazil from the 1790s, and second, by the agreements of 1815 and 1817 between Britain and Portugal, which (on paper at least) limited Portuguese slave trading to areas south of the equator.[3] This trade diminished after Brazilian independence in 1822, and more sharply following an agreement between Britain and Brazil in 1830 by which the Brazilian government prohibited further slave imports.[4] To find slaves for export from the Angolan towns, Afro-Portuguese traders had penetrated as far inland as Katanga and Kazembe, but otherwise there was little penetration of the interior and no attempt to establish control there.[5] When the Brazilian slave trade declined, slaves were used on Portuguese plantations which stretched inland of Luanda along the Cuanza River and to a lesser extent around Benguela. After Moçâmedes had been founded south of Benguela in 1840 and Ambriz had been occupied in 1855, Portugal controlled a continuous coastal strip from Ambriz to Moçâmedes, but little inland territory.[6] Although Portugal claimed to control the Congo River estuary, Britain would at best accept it had limited rights in the Cabinda enclave north of the river, although these rights did not make Cabinda Portuguese territory.[7][8]

Portugal had occupied parts of the coast of Mozambique from the 16th century, but at the start of the 19th century its presence was limited to Mozambique Island, Ibo and Quelimane in northern Mozambique, outposts at Sena and Tete in the Zambezi valley, Sofala to the south of the Zambezi and a port town at Inhambane further south again. Although Delagoa Bay was regarded as Portuguese territory, Lourenço Marques was not settled until 1781, and was temporarily abandoned after a French raid in 1796.[9] In the late 18th century, most of the slaves exported through the Portuguese settlements in Mozambique were sent to Mauritius and Réunion, at that time both French colonies, but this trade was disrupted by wars with France, and in the early 19th century many slaves were sent to Brazil.[10] As was the case with Angola, slave exports declined after 1830, but were partly replaced by exports of ivory through Lourenço Marques from the 1840s onward.[11]

The nadir of Portuguese fortunes in Mozambique was reached in the 1830s and 1840s when Lourenço Marques was sacked in 1833 and Sofala in 1835. Zumbo was abandoned in 1836 and Afro-Portuguese settlers near Vila de Sena were forced to pay tribute to the Gaza.[12] Although Portugal claimed sovereignty over Angoche and a number of smaller Muslim coastal towns, these were virtually independent at the start of the 19th century. However, after Portugal had renounced the slave trade, these towns carried it on and, fearing British or French intervention, Portugal began to bring these towns under more effective control. Angoche resisted and fought off a Portuguese warship attempting to prevent slave-trading in 1847. It took a military expedition and occupation in 1860-1 to end its slave trading.[13] Portugal had also initiated the Prazo system of large leased estates under nominal Portuguese rule in the Zambezi valley. By the end of the 18th century, the valleys of the Zambezi and lower Shire River were controlled by a few families that claimed to be Portuguese subjects but which were virtually independent. However, from 1840 the Portuguese government embarked on a series of military campaigns in an attempt to bring the prazos under its effective control. The Portuguese troops suffered several major setbacks before the last of the prazos was forced to submit in 1869.[14]

In other inland areas, there was not even a pretence of Portuguese control. In the interior of what is today southern and central Mozambique, Nguni who had entered the area from South Africa under their leader Soshangane created the Gaza Empire in the 1830s and, up to Soshangane's death in 1856, this dominated southern Mozambique outside the two towns of Inhambane and Lourenço Marques. Lourenço Marques only remained in Portuguese hands in the 1840s and early 1850s because the Swazi vied with the Gaza for its control.[15] After Soshangane's death, there was a succession struggle between two of his sons, and the eventual winner Mzila came to power with Portuguese help in 1861. Under Mzila, the centre of Gaza power moved north to central Mozambique, and came into conflict with the prazo owners who were expanding south from the Zambezi valley.[16]

As was the case with Angola, in the 18th century Afro-Portuguese traders employed by the Mozambique prazo owners penetrated inland from the Zambezi valley as far as Kazembe in search of ivory and copper. In 1798, Francisco de Lacerda, a Portuguese officer based in Mozambique, organised an expedition from Tete to the interior, hoping to reach Kazembe, but he died en route in what is now Zambia. Apart from Lacerda's expedition, none of the trading ventures into the interior from Angola or Mozambique had any official status and were not attempts to bring the area between Angola and Mozambique under Portuguese control. Even Lacerda's expedition was largely commercial in purpose, although it was later claimed to have established some claim to the area he covered. In 1831, Antonio Gamitto also tried to establish commercial relations with Kazembe and peoples in the upper Zambezi valley, but without success.[17]

After the loss of Brazil and all but a few enclaves in Asia, Portuguese colonial expansion focused on Africa. However, the position in the late 1860s was that it had no effective presence in the area between Angola and Mozambique, and very little in many areas lying within the present-day borders of those countries. By the second half of the 19th century, various European powers had an increasing interest in Africa. The first challenge to Portugal's territorial claims came from the area around Delagoa Bay. The Boers who had founded the Transvaal Republic were concerned that British occupation of the bay would reduce their independence, and to prevent this they claimed their own outlet to the Indian Ocean at Delagoa Bay in 1868. Although Portugal and the Transvaal reached agreement in 1869 on a border under which all of Delagoa Bay remained Portuguese, Britain then lodged a claim to the southern part of that bay. This claim was rejected after arbitration by President MacMahon. His award made in 1875 upheld the border agreed in 1869.[18]

A further significant issue arose in the areas south and west of Lake Nyasa, (now Lake Malawi),which had been explored by David Livingstone in the 1850s. Several Church of England and Presbyterian missions were established in the Shire Highlands in the 1860s and 1870s including a mission and small trading settlement founded at Blantyre in 1876. In 1878 the African Lakes Company was established by businessmen with links to the Presbyterian missions. The company's aim was to set up a trading venture that would work in close co-operation with the missions to combat the slave trade by introducing legitimate trade and develop European influence in the area.[19] Rather later, another challenge came from the foundation of a German colony at Angra Pequena, now known as Lüderitz, in Namibia in 1883. Although there was no Portuguese presence this far south, Portugal had claimed the Namibian coast on the basis of earlier discovery.[20]

Portuguese exploration and attempts at negotiation

Although the expeditions of Lacerda and Gamitto were largely commercial, the third quarter of the nineteenth century saw scientific African expeditions. The Portuguese government was suspicious that the efforts of explorers from other European nations, particularly those whose leasers held some official, often consular, position (as Livingstone had), could be used by their home nations to claim territory Portugal regarded as its own. To prevent this, the Lisbon Geographical Society and the Geographical Commission of the Portuguese Ministry of Marine, which at that time had responsibility for overseas territories as well as the navy, created a joint commission in 1875, which planned scientific expeditions to the area between Angola and Mozambique.[21] Although the Minister, Andrade Corvo, doubted Portugal's ability to achieve a coast-to-coast empire, he sanctioned the expeditions for their scientific value. Despite their mixed aims, three expeditions led by Alexandre de Serpa Pinto were undertaken, through which Portugal could attempt to assert its African territorial claims. The first was from Mozambique to the eastern Zambezi in 1869, the second to the Congo and upper Zambezi from Angola in 1876 and the last in 1877–79 crossing Africa from Angola, with the intention of claiming the area between it and Mozambique. Also in 1877, Hermenegildo Capelo and Roberto Ivens led an expedition from Luanda towards the Congo basin. Capelo made a second journey from Angola to Mozambique, largely following existing trade routes, in 1884-5.[22][23]

Both during and after the expeditions of Serpa Pinto and Capelo, the Portuguese government attempted bi-lateral negotiations with Britain. In 1879, as part of talks on a treaty on the freedom of navigation on the Congo and Zambezi rivers and the development of trade in those river basins, the Portuguese government made a formal claim to the area south and east of the Ruo River (the present south-eastern border of Malawi).[24] The 1879 treaty was never ratified, and in 1882 Portugal occupied the lower Shire River valley as far as the Ruo, after which its government again asked the British government to accept this territorial claim, without success.[25] Further bi-lateral negotiations led to a draft treaty in February 1884, which would have included British recognition of Portuguese sovereignty over the mouth of the Congo in exchange for freedom of navigation on the Congo and Zambezi rivers but the opening of the Berlin Conference of 1884–85 ended these discussions, which could have led to British recognition of Portuguese influence stretching across the continent.[26] Portugal's efforts to establish a corridor of influence between Angola and Mozambique without gaining full political control were hampered by one of the articles in the General Act of the Berlin Conference requiring effective occupation of areas claimed rather than relying on historical claims based on early discovery or more recent claims based largely on exploration, as Portugal wished to use.[27]

To validate Portuguese claims, Serpa Pinto was appointed as its consul in Zanzibar in 1884, with the mission of exploring the region between Lake Nyasa and the coast from the Zambezi to the Rovuma River and securing the allegiance if the chiefs in that area.[28] His expedition reached Lake Nyasa and the Shire Highlands, but failed make any treaties of protection with the chiefs in territories west of the lake.[29] At the northwest end of Lake Nyasa around Karonga, the African Lakes Company made, or claimed to have made, treaties with local chiefs between 1884 and 1886. Its ambition was to become a Chartered company and control the route from the Lake along the Shire River. Its further ambition to control the Shire Highlands was given up in 1886 following protests from local missionaries that it could not police this area effectively.[30]

The Berlin Conference

The General Act of the Berlin Conference dated 26 February 1885, which introduced the principle of effective occupation, was potentially damaging to Portuguese claims, particularly in Mozambique where other powers were active. Article 34 required a nation acquiring land on the coasts of Africa outside of its previous possessions to notify the other signatories of the Act so they could protest against such claims. Article 35 of the Act provided that rights could only be acquired over previously uncolonised lands if the power claiming them had established sufficient authority there to protect existing rights and the freedom of trade. This normally implied making treaties with local rulers, establishing an administration and exercising police powers. Initially, Portugal claimed that the Berlin Treaty did not apply, and it was not required to issue notifications or establish effective occupation, as Portugal's claim to the Mozambique coast had existed for centuries and had been unchallenged.[31][32]

However, British officials did not accept this interpretation, and in January 1884 Henry O'Neill, the British consul based at Mozambique Island said that:

- "To speak of Portuguese colonies in East Africa is to speak of a mere fiction—a fiction colourably sustained by a few scattered seaboard settlements, beyond whose narrow littoral and local limits colonisation and government have no existence."[33]

To forestall British designs on the parts of Mozambique and the interior that O'Neill claimed Portugal did not occupy, Joaquim Carlos Paiva de Andrada was commissioned in 1884 to establish effective occupation, and he was active in four areas. Firstly, in 1884 he established the town of Beira and Portuguese occupation of much of Sofala Province. Secondly, also in 1884, he acquired a concession of an area within a 180 kilometre radius of Zumbo, which had been reoccupied and west of which Afro-Portuguese families had traded and settled since the 1860s. Although Andrada did not establish any administration immediately, in 1889 an outpost was established beyond the junction of the Zambezi and Kafue River and an administrative district was established based on Zumbo .[34][35][36] Thirdly, in 1889 Andrada was granted another concession over Manica, which covered the areas both of the Manica Province of Mozambique and the Manicaland Province of Zimbabwe. Andrada succeeded in obtaining treaties over much of this area and establishing a rudimentary administration but he was arrested in November 1890 by British South Africa Company troops and expelled. Finally, also in 1889, Andrada crossed northern Mashonaland, approximately the area of the Mashonaland Central Province of Zimbabwe, to obtaining treaties. He failed to inform the Portuguese government of these treaties, so these claims were not formally notified to other powers, as required by the Berlin Treaty.

The Pink Map

Despite the outcome of the Berlin Conference and the failure of bi-lateral negotiations with Britain, Portugal did not abandon the idea of securing a trans-African colonial zone. In 1885, the Portuguese Foreign Minister, Barros Gomes, published what became known as the Pink or Rose-Coloured Map, which represented a formal Portuguese claim to sovereignty over an area defined by the map that stretched from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean.[37] Portugal also signed treaties with France and Germany in 1886. To obtain the French treaty, Portugal agreed to give up any claim to the area around the Casamance River in Guinea in exchange for a vague recognition of its rights to exercise sovereignty in an undefined area between Angola and Mozambique, although the Rose-Coloured Map was attached to the treaty for information. To obtain the treaty with Germany noting Portugal's claim to territory along the course of the Zambezi linking Angola and Mozambique and with the Rose-Coloured Map attached, Portugal agreed to accept a southern boundary for Angola and a northern boundary for Mozambique that were favourable to Germany. The acts of "noting" the Portuguese claims and attaching the Rose-Coloured Map to each treaty did not amount to France or Germany accepting the claims, only that Portugal had made them.[38][39]

Lord Salisbury formally protested against the Rose-Coloured Map, but initially made no British claim to any of the territories it concerned. Further, in July 1887, Salisbury stated that the British government would not accept any Portuguese claim to an area unless there were sufficient Portuguese forces to maintain order. The Portuguese government therefore considered that this meant that Britain would accept a claim backed by effective occupation.[40] Later in 1887, the British Minister in Lisbon proposed that the Zambezi should be recognised as the northern limit of British influence, which would have left the Scottish missionaries in the Shire Highlands within the Portuguese zone and created a band of Portuguese territory linking Angola and Mozambique, although one significantly smaller than the Rose-Coloured Map proposed, as all of what is now Zimbabwe would be British territory. This was rejected by Portugal because the Shire Highlands and their missions could at that time only be accessed through coastal areas acknowledged as Portuguese, and because the proposal would involve giving up the southern and more valuable half of the transcontinental zone claimed the Rose-Coloured Map, apparently for little in return.[41]

By 1889 the Portuguese government felt less confident and its Foreign Minister, Barros Gomes, proposed to the British government that it was willing to abandon its claim to a zone linking Angola and Mozambique in exchange for recognition of its claim to the Shire Highlands. This time, it was the British government that rejected the proposal, firstly because of the strong opposition of those supporting the Scottish missions, and secondly, because the Chinde River entrance to the Zambezi had been discovered in April 1889. As the Zambezi could now be directly entered by ocean-going ships, it and its tributary the Shire River could be regarded as an international waterway giving access to the Shire Highlands.[42]

It is sometimes suggested that the Rose-Coloured Map was made as a direct challenge to Cecil Rhodes and particularly his vision of a "Cape to Cairo Red Line". The Cape to Cairo idea was first put forward by Henry Hamilton Johnston in a newspaper article in August 1888 three years after the map was published, and only later take over by Rhodes. His British South Africa Company was founded in October 1888 and only received its Royal Charter enabling it to trade with local rulers, to acquire own and sell land and operate a police force in Matabeleland and adjacent areas south of the Zambezi in October 1889 .[43] However, from the incorporation of the British South Africa Company, Rhodes and the company were the main opponents of Portuguese claims south of the Zambezi, and Rhodes made no secret of his intention to take over part of the Mozambique to gain an outlet to the Indian Ocean.[44] North of the Zambezi, Portuguese claims to the Shire Highlands were opposed both by the African Lakes Company and the missionaries, the latter supported by public opinion, especially in Scotland as many missionaries were Scots.[45] As late as 1888, the British Foreign Office declined to offer protection to the tiny British settlements in the Shire Highlands. It did not accept an expansion of Portuguese influence there, and in 1889 it appointed Harry Johnson as British consul to Mozambique and the Interior, and instructed him to report on the extent of Portuguese rule in the Zambezi and Shire valleys. He was also to make conditional treaties with local rulers outside Portuguese control. These conditional treaties did not establish a British protectorate, but prevented the rulers from accepting protection from another state.[46]

In 1888, Portuguese government representatives in Mozambique organised two expeditions to make treaties of protection with the Yao chiefs southeast of Lake Nyasa and in the Shire Highlands to establish Portuguese territorial claims. The first one, under Antonio Cardosa, a former governor of Quelimane set off in November 1888 for Lake Nyasa. The second expedition under Serpa Pinto, (now governor of Mozambique) moved up the Shire valley. Between them, the expeditions made over 20 treaties with chiefs in what is now Malawi.[47] The expedition led by Pinto was well armed, partly in response to a request from the Portuguese resident on the lower Shire for help in resolving disturbances caused by the Makololo chiefs. The Makololo had been brought into the area by David Livingstone as part of his Zambezi expedition, and remained on the Shire north and west of the Ruo river when it ended in 1864. They claimed to be outside Portuguese control, and asked for British assistance to remain independent.[48] Serpa Pinto met Johnston in August 1889 east of the Ruo, when Johnston advised him not to cross the river into the Shire Highlands.[49]

Members of the British community in the Shire Highlands probably encouraged the Makololo to attack Serpa Pinto, which led to a minor battle between Pinto’s Portuguese troops and the Makololo on 8 November 1889 near the Shire river.[50] Although Serpa Pinto had previously acted with caution, he now crossed the Ruo into what is now Malawi.[51] When Serpa Pinto occupied much of Makololo territory, Johnston's vice-consul, John Buchanan, accused Portugal of ignoring British interests in this area and declared a British protectorate over the Shire Highlands in December 1889, despite contrary instructions.[50] Shortly after this, Johnston himself declared a further protectorate over the area to the west of Lake Nyasa, also contrary to his instructions, although both protectorates were later endorsed by the Foreign Office.[52] These actions formed the background to an Anglo-Portuguese Crisis in which a British refusal of arbitration was followed by the 1890 British Ultimatum.[53]

The 1890 British Ultimatum

The British Ultimatum of 1890 is a memorandum sent to the Portuguese Government by Lord Salisbury on 11 January 1890 in which he demanded the withdrawal of the Portuguese troops from Mashonaland and Matabeleland (now Zimbabwe) and the area between the Shire river north of the Ruo and Lake Nyasa (including all the Shire Highlands), where Portuguese and British interests in Africa overlapped. It meant that Britain was now claiming sovereignty over some territories which Portugal had claimed for centuries. There was no dispute regarding the borders of Angola, as neither country had effectively occupied any part of the sparsely populated border area.[54] It has been plausibly argued that Lord Salisbury, whose government was diplomatically isolated, used tactics that could have led to a war through fear of being humiliated by a Portuguese success.[55] The Ultimatum was accepted by King Carlos I of Portugal and it caused violent anti-British demonstrations in Portugal leading to riots. Portuguese Republicans used it as an excuse to attack the government, and staged a coup d’etat in Oporto in January 1891.[56]

Although the Ultimatum required Portugal to cease from activity in the disputed areas, there was no similar restriction on further British occupation there. Between the British issuing this ultimatum to Portugal on 11 January 1890 and the signing of a treaty in Lisbon on 11 June 1891, both Britain and Portugal tried to occupy more of the disputed areas and assert their authority. Although a rudimentary Portuguese administration had been established in Manicaland in 1884 and strengthened this in 1889 before there was any British South Africa Company presence in the area, in November 1890, British South Africa Company troops arrested and expelled the Portuguese officials in an attempt to gain access to the coast and there were armed clashes between Rhodes’ men and Portuguese troops who were already in occupation in Manicaland. Although the British government refused to accept this completely, fighting only ceased when Rhodes' company was awarded part of Manicaland. Buchanan asserted British sovereignty on the Shire Highlands by executing two Portuguese cipais (African soldiers), claiming they were within British jurisdiction.[57]

The General Act of the Berlin Conference required disputes to go to arbitration. After the Ultimatum Portugal asked for arbitration, but because the 1875 Delagoa Bay arbitration had been in favour of Portugal, Lord Salisbury refused and demanded a bi-lateral treaty. Talks started in Lisbon in April 1890, and in May the Portuguese delegation proposed joint administration of the disputed area between Angola and Mozambique. The British government refused this, and drafted a treaty that imposed boundaries that were generally unfavourable to Portugal.[58] This led to a wave of protests and the downfall of the Portuguese government in when the draft treaty was published.[56] This treaty did however grant Portugal special right to build a railway, road and telegraph line along the north bank of the Zambezi, which would have provided a limited link between Angola and Mozambique.[59]

The refusal of the Portuguese Parliament to ratify the agreement in August 1890 led to a new treaty being negotiated, which gave Portugal more territory in the Zambezi valley than the 1890 treaty, in exchange for giving up what is now the Manicaland Province of Zimbabwe. This treaty, which also fixed the borders of Angola, was signed in Lisbon on 11 June 1891, and in addition to defining boundaries it provided for freedom of navigation on the Zambezi and Shire rivers. However, it gave Portugal no special rights along the north bank of the Zambezi, so it finally ended the Pink Map project.[60]

References

- ↑ C E Nowell, (1982). The rose-colored map: Portugal's attempt to build an African empire from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean.

- ↑ R Oliver and A Atmore, (1986). The African Middle Ages, 1400–1800, pp. 163–4, 191, 195.

- ↑ J C Miller, (1988). Way of Death: Merchant Capitalism and the Angolan Slave Trade, 1730–1830, pp. 261, 269–70.

- ↑ J C Miller, (1988). Way of Death: Merchant Capitalism and the Angolan Slave Trade, 1730–1830, p. 637.

- ↑ R Oliver and A Atmore, (1986). The African Middle Ages, 1400–1800, pp. 137.

- ↑ P E Lovejoy, (2012). Transformations in Slavery, 3rd edition, pp. 230–1.

- ↑ W. G. Clarence-Smith, (1985)The Third Portuguese Empire 1825–1975, p. 36

- ↑ R J Hammond, (1966). Portugal and Africa: 1815–1910, pp. 54–5.

- ↑ M Newitt, (1995). A History of Mozambique, pp. 129, 137, 159–63.

- ↑ P E Lovejoy, (2012). Transformations in Slavery, 3rd edition, p. 146.

- ↑ M Newitt, (1995). A History of Mozambique, pp. 248, 292–3.

- ↑ M Newitt, (1995). A History of Mozambique, pp. 260, 282, 287.

- ↑ M Newitt, (1995). A History of Mozambique, pp. 272–5.

- ↑ M Newitt, (1969). The Portuguese on the Zambezi: An Historical Interpretation of the Prazo system, pp. 67–8, 80–2.

- ↑ M Newitt, (1995). A History of Mozambique, pp. 262, 293–5.

- ↑ M Newitt, (1995). A History of Mozambique, pp. 289–91.

- ↑ M Newitt, (1995). A History of Mozambique, pp. 211, 229, 268, 276.

- ↑ M Newitt, (1995). A History of Mozambique, pp. 327–9.

- ↑ J G Pike, (1969). Malawi: A Political and Economic History, pp.77–9.

- ↑ H. Livermore (1992), Consul Crawfurd and the Anglo-Portuguese Crisis of 1890, pp. 181–2.

- ↑ M Newitt, (1995). A History of Mozambique, pp. 334–5.

- ↑ C E Nowell, (1947). Portugal and the Partition of Africa, pp. 6–8.

- ↑ M Newitt, (1995). A History of Mozambique, pp. 335–6.

- ↑ M Newitt, (1995). A History of Mozambique, p. 330.

- ↑ J McCracken, (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859–1966, p. 51.

- ↑ M Newitt, (1995). A History of Mozambique, pp. 331–2.

- ↑ Teresa Pinto Coelho, (2006). Lord Salisbury's 1890 Ultimatum to Portugal and Anglo-Portuguese Relations, p. 2. http://www.mod-langs.ox.ac.uk/files/windsor/6_pintocoelho.pdf

- ↑ C E Nowell, (1947). Portugal and the Partition of Africa, p. 10.

- ↑ M Newitt, (1995). A History of Mozambique, pp. 276–7, 325–6.

- ↑ J McCracken, (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859–1966, pp. 48–52.

- ↑ A Keppel-Jones (1983) Rhodes and Rhodesia: The White Conquest of Zimbabwe 1884–1902, pp 190–1.

- ↑ The General Act of the Berlin Conference. http://africanhistory.about.com/od/eracolonialism/l/bl-BerlinAct1885.htm

- ↑ Quoted in J C Paiva de Andrada, (1885). Relatorio de uma viagem ás terras dos Landins, at Project Gutenberg, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/34041/34041-h/34041-h.htm

- ↑ J C Paiva de Andrada, (1886). Relatorio de uma viagem ás terras do Changamira, at Project Gutenberg, https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/34040/34040-h/34040-h.htm .

- ↑ J C Paiva de Andrada, (1885). Relatorio de uma viagem ás terras dos Landins,

- ↑ M Newitt, (1995). A History of Mozambique, pp. 337–8, 344.

- ↑ W. G. Clarence-Smith, (1985)The Third Portuguese Empire 1825–1975, p. 83

- ↑ M Newitt, (1995). A History of Mozambique, pp. 341–3.

- ↑ Teresa Pinto Coelho, (2006). Lord Salisbury's 1890 Ultimatum to Portugal and Anglo-Portuguese Relations, pp. 2–3.

- ↑ H V Livermore, (1966) A New History of Portugal, pp. 305–6.

- ↑ M Newitt, (1995). A History of Mozambique, pp. 343–4.

- ↑ M Newitt, (1995). A History of Mozambique, pp. 337, 345–6.

- ↑ H V Livermore, (1966) A New History of Portugal, pp. 306–7.

- ↑ R I Rotberg, (1988). The Founder: Cecil Rhodes and the Pursuit of Power, pp. 304–12

- ↑ M Newitt, (1995). A History of Mozambique, p. 341.

- ↑ J G Pike, (1969). Malawi: A Political and Economic History, pp. 83–5.

- ↑ J McCracken, (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859–1966, pp. 52–3.

- ↑ M Newitt, (1995). A History of Mozambique, pp. 282, 346.

- ↑ J G Pike, (1969). Malawi: A Political and Economic History, pp. 85–6.

- 1 2 M Newitt, (1995). A History of Mozambique, pp. 346–7.

- ↑ J McCracken, (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859–1966, pp. 53, 55.

- ↑ R I Rotberg, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa: The Making of Malawi and Zambia, 1873–1964, p.15.

- ↑ F Axelson, (1967). Portugal and the Scramble for Africa, pp. 233–6.

- ↑ Teresa Pinto Coelho, (2006). Lord Salisbury's 1890 Ultimatum to Portugal and Anglo-Portuguese Relations, p. 1.

- ↑ M Newitt, (1995). A History of Mozambique, p. 347.

- 1 2 Teresa Pinto Coelho, (2006). Lord Salisbury's 1890 Ultimatum to Portugal and Anglo-Portuguese Relations, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ M Newitt, (1995). A History of Mozambique, pp. 350–1, 354–5.

- ↑ M Newitt, (1995). A History of Mozambique, pp. 347, 352–3.

- ↑ M Newitt, (1995). A History of Mozambique, p. 353.

- ↑ Teresa Pinto Coelho, (2006). Lord Salisbury's 1890 Ultimatum to Portugal and Anglo-Portuguese Relations, pp. 6–7.

Sources

- C E Nowell, (1982). The rose-coloured map: Portugal's attempt to build an African empire from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean

- W. G. Clarence-Smith, (1985). The Third Portuguese Empire 1825–1975: A Study in Economic Imperialism, Manchester University Press.ISBN 978-0-719-01719-3

- P E Lovejoy, (2012). Transformations in Slavery, 3rd edition. Cambridge University Press ISBN 978-0-521-17618-7.

- R J Hammond, (1966). Portugal and Africa 1815–1910: a Study in Uneconomic Imperialism, Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-804-70296-9

- M Newitt, (1995). A History of Mozambique, London, Hurst & Co. ISBN 1-85065-172-8.

- M Newitt, (1969). The Portuguese on the Zambezi: An Historical Interpretation of the Prazo system, Journal of African History Vol X, No 1.

- J G Pike, (1969). Malawi: A Political and Economic History, London, Pall Mall Press.

- J C Paiva de Andrada, (1885). Relatorio de uma viagem ás terras dos Landins, at Project Gutenberg, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/34041/34041-h/34041-h.htm

- J C Paiva de Andrada, (1886). Relatorio de uma viagem ás terras do Changamira, at Project Gutenberg, https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/34040/34040-h/34040-h.htm

- H. Livermore (1992). Consul Crawfurd and the Anglo-Portuguese Crisis of 1890, Portuguese Studies, Vol. 8.

- C E Nowell, (1947). Portugal and the Partition of Africa, The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 19, No. 1.

- A Keppel-Jones (1983) Rhodes and Rhodesia: The White Conquest of Zimbabwe 1884–1902, McGill-Queen's Press. ISBN 978-0-773-56103-8

- General Act of the Berlin Conference. http://africanhistory.about.com/od/eracolonialism/l/bl-BerlinAct1885.htm

- J McCraken, (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859–1966, Woodbridge, James Currey. ISBN 978-1-84701-050-6.

- H V Livermore, (1966). A New History of Portugal, Cambridge University Press.

- R I Rotberg, (1988). The Founder: Cecil Rhodes and the Pursuit of Power, Oxford University Press ISBN 978-0195049688

- R I Rotberg, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa: The Making of Malawi and Zambia, 1873–1964, Cambridge (Mass), Harvard University Press.

- F Axelson, (1967). Portugal and the Scramble for Africa, Johannesburg, Witwatersrand University Press.

- F Tamburini, (2014) Il ruolo dell'Italia nella vertenza anglo-portoghese sui territori dell'Africa australe: dal mapa-cor-de-rosa al Barotseland (1886-1905), "Africana, rivista di studi extraeuropei".