Polar climate

The polar climate regions are characterized by a lack of warm summers. Every month in a polar climate has an average temperature of less than 10 °C (50 °F). Regions with polar climate cover more than 20% of the Earth. The sun shines for long hours in the summer, and for many fewer hours in the winter. A polar climate results in treeless tundra, glaciers, or a permanent or semi-permanent layer of ice. It has cool summers and very cold winters.

Subtypes

There are two types of polar climate: ET, or tundra climate; and EF, or ice cap climate. A tundra climate is characterized by having at least one month whose average temperature is above 0 °C (32 °F), while an ice cap climate has no months above 0 °C (32 °F).[2] In a tundra climate, trees cannot grow, but other specialized plants can grow. In an ice cap climate, no plants can grow, and ice gradually accumulates until it flows elsewhere. Many high altitude locations on Earth have a climate where no month has an average temperature of 10 °C (50 °F) or higher, but as this is due to elevation, this climate is referred to as Alpine climate. Alpine climate can mimic either tundra or ice cap climate.

Locations

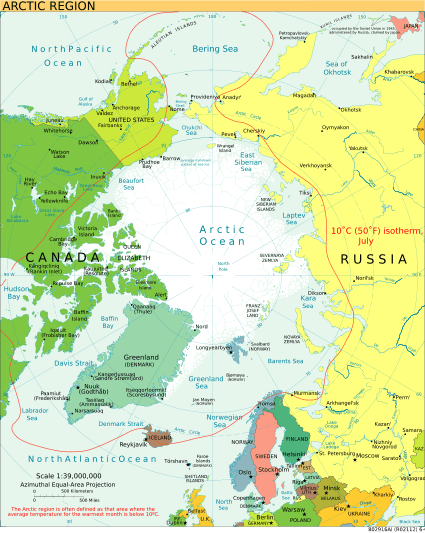

On Earth, the only continent where the ice cap polar climate is predominant is Antarctica. All but a few isolated coastal areas on the island of Greenland also have the ice cap climate. Coastal regions of Greenland that do not have permanent ice sheets have the less extreme tundra climates. The northernmost part of the Eurasian land mass, from the extreme northeastern coast of Scandinavia and eastwards to the Bering Strait, large areas of northern Siberia and northern Iceland have tundra climate as well. Large areas in northern Canada and northern Alaska have tundra climate, changing to ice cap climate in the most northern parts of Canada. Southernmost South America (Tierra del Fuego where it abuts the Drake Passage) and such subantarctic islands such as the South Shetland Islands and the Falkland Islands have tundra climates of slight thermal range in which no month is as warm as 10 °C (50 °F). These subantarctic lowlands are found closer to the equator than the coastal tundras of the Arctic basin.

Arctic

Some parts of the Arctic are covered by ice (sea ice, glacial ice, or snow) year-round, and nearly all parts of the Arctic experience long periods with some form of ice on the surface. Average January temperatures range from about −40 to 0 °C (−40 to 32 °F), and winter temperatures can drop below −50 °C (−58 °F) over large parts of the Arctic. Average July temperatures range from about −10 to 10 °C (14 to 50 °F), with some land areas occasionally exceeding 30 °C (86 °F) in summer.

The Arctic consists of ocean that is nearly surrounded by land. As such, the climate of much of the Arctic is moderated by the ocean water, which can never have a temperature below −2 °C (28 °F). In winter, this relatively warm water, even though covered by the polar ice pack, keeps the North Pole from being the coldest place in the Northern Hemisphere, and it is also part of the reason that Antarctica is so much colder than the Arctic. In summer, the presence of the nearby water keeps coastal areas from warming as much as they might otherwise, just as it does in temperate regions with maritime climates.

Antarctica

The climate of Antarctica is the coldest on the whole of Earth. Antarctica has the lowest temperature ever recorded: −89.2 °C (−128.6 °F) at Vostok Station.[4] It is also extremely dry (technically a desert), averaging 166 millimetres (6.5 in) of precipitation per year. Even so, on most parts of the continent the snow rarely melts and is eventually compressed to become the glacial ice that makes up the ice sheet. Weather fronts rarely penetrate far into the continent.

Quantifying polar climate

There have been several attempts at quantifying what constitutes a polar climate.

Climatologist Wladimir Köppen demonstrated a relationship between the Arctic and Antarctic tree lines and the 10 °C (50 °F) summer isotherm; i.e., places where the average temperature in the warmest calendar month of the year is below 10 °C (50 °F) cannot support forests. See Köppen climate classification for more information.

Otto Nordenskjöld theorized that winter conditions also play a role: His formula is W = 9 − 0.1 C, where W is the average temperature in the warmest month and C the average of the coldest month, both in degrees Celsius (this would mean, for example, that if a particular location had an average temperature of −20 °C (−4 °F) in its coldest month, the warmest month would need to average 11 °C (52 °F) or higher for trees to be able to survive there as 9 - 0.1(-20) = 11). Nordenskiöld's line tends to run to the north of Köppen's near the west coasts of the Northern Hemisphere continents, south of it in the interior sections, and at about the same latitude along the east coasts of both Asia and North America. In the Southern Hemisphere, all of Tierra del Fuego lies outside the polar region in Nordenskiöld's system, but part of the island (including Ushuaia, Argentina) is reckoned as being within the Antarctic under Köppen's.

In 1947, Holdridge improved on these schemes, by defining biotemperature: the mean annual temperature, where all temperatures below 0 °C (32 °F) (and above 30 °C (86 °F)) are treated as 0 °C (32 °F) (because it makes no difference to plant life, being dormant). If the mean biotemperature is between 1.5 and 3 °C (34.7 and 37.4 °F),[5] Holdridge quantifies the climate as subpolar (or alpine, if the low temperature is caused by altitude).

See also

References

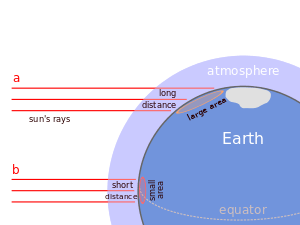

- ↑ Yung, Chung-hoi. "Why is the equator very hot and the poles very cold?". Hong Kong Observatory. Retrieved 2010-12-02.

- ↑ McKnight, Tom L; Hess, Darrel (2000). "Climate Zones and Types: The Köppen System". Physical Geography: A Landscape Appreciation. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. pp. 235–7. ISBN 0-13-020263-0.

- ↑

This article incorporates public domain material from the CIA World Factbook website https://web.archive.org/web/20070613024704/https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/reference_maps/pdf/arctic.pdf.

This article incorporates public domain material from the CIA World Factbook website https://web.archive.org/web/20070613024704/https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/reference_maps/pdf/arctic.pdf. - ↑ Gavin Hudson (2008-12-14). "The Coldest Inhabited Places on Earth". Eco Worldly. Archived from the original on 2008-12-18. Retrieved 2009-02-08.

- ↑ Biodiversity lectures and practicals of Allan Jones

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Polar climate. |