Polygonal patterned ground

Polygonal, patterned ground is quite common in some regions of Mars.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7] It is commonly believed to be caused by the sublimation of ice from the ground. Sublimation is the direct change of solid ice to a gas. This is similar to what happens to dry ice on the Earth. Places on Mars that display polygonal ground may indicate where future colonists can find water ice. Patterned ground forms in a mantle layer, called latitude dependent mantle, that fell from the sky when the climate was different.[8][9][10][11]

-

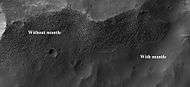

Surface showing appearance with and without mantle covering, as seen by HiRISE, under the HiWish program. Location is Terra Sirenum in Phaethontis quadrangle.

-

Mantle layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Location is Eridania quadrangle

-

Close up view of mantle, as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program. Mantle may be composed of ice and dust that fell from the sky during past climatic conditions. Location is Cebrenia quadrangle.

Polygons in Casius quadrangle

-

Low center polygons, shown with arrows, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program Loacation is Casius quadrangle. Image was enlarged with HiView.

-

High center polygons, shown with arrows, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Loacation is Casius quadrangle. Image enlarged with HiView.

-

Scalloped terrain labeled with both low center polygons and high center polygons, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program Loacation is Casius quadrangle. Image enlarged with HiView.

-

Low center polygons, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program Loacation is Casius quadrangle. Image enlarged with HiView.

-

High and low center polygons, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program Loacation is Casius quadrangle. Image enlarged with HiView.

Polygons in Hellas quadrangle

-

Patterned ground in Hellas, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program The rectangle shows the size of a football field.

-

Close view of snout of glacier, as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program High center polygons are visible. Box shows size of football field.

-

Close view of high center ploygons near glacier, as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program

-

Close view of high center ploygons near glacier, as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program Box shows size of football field.

-

Close view of high center ploygons near glacier, as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program

Sizes and formation of polygonal ground

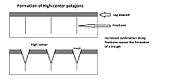

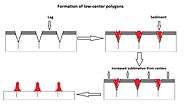

Polygonal ground is generally divided into two kinds: high center and low center. The middle of a high center polygon is 10 meters across and its troughs are 2–3 meters wide. Low center polygons are 5–10 meters across and the boundary ridges are 3–4 meters wide.[12]

-

Drawing with a side view showing sizes of high and low center polygons

High center polygons are higher in the center and lower along their boundaries. It forms from increased sublimation around cracks in a surface. Cracks are common in ice-rich surfaces.[13][14] [15][16][17][18][19]

The cracks provide a place of increased surface area for sublimation. After a time the narrow cracks widen to become troughs.

-

Drawing showing formation of high center polygons. Ice-rich mantle develops a lag deposit. Stresses create cracks. Increased sublimation along cracks causes troughs.

Low center polygons are thought to develop from the high center polygons. The troughs along the edges of high center polygons may become filled with sediment. This thick sediment will retard sublimation, so more sublimation will take place in the center that is protected by a thinner lag deposit. In time, the middle becomes lower than the outer parts. The sediments from the troughs will turn into ridges.[12]

-

Diagram showing how low center polygons develop. The troughs of high center polygons fill with sediment; consequently there is much less sublimation there and more at the center.

High-center polygons in Ismenius Lacus quadrangle

-

High-center polygons, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program Image is of the top of a debris apron in Deuteronilus Mensae.

-

Close up of field of high center polygons with scale, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program Note: the black box is the size of a football field.

-

Close-up of high center polygons seen by HiRISE under HiWish program Note: the black box is the size of a football field.

-

Close-up of high center polygons seen by HiRISE under HiWish program Troughs between polygons are easily visible in this view.

-

high center polygons seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Wide view of high center polygons, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Close view of high center polygons, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program Centers of polygons are labeled.

Latitude dependent mantle

Much of the Martian surface is covered with a thick ice-rich, mantle layer that has fallen from the sky a number of times in the past. It fell as snow and ice-coated dust. This mantle layer is called "latitude dependent mantle" because its occurrence is related to the latitude. It is this mantle that cracks and then forms polygonal ground.

The mantle layer lasts for a very long time before all the ice is gone because a protective lag deposit forms on the top.[20] The mantle contains ice and dust. After a certain amount of ice disappears from sublimation the dust stays on the top, forming the lag deposit.[21][22][23]

Mantle forms when the Martian climate is different than the present climate. The tilt or obliquity of the axis of the planet changes a great deal.[24][25][26] The Earth’s tilt changes little because our rather large moon stabilizes the Earth. Mars only has two very small moons that do not possess enough gravity to stabilize its tilt. When the tilt of Mars exceeds around 40 degrees (from today's 25 degrees), ice is deposited in certain bands where much mantle exists today.[27][28]

Other surface features

Another type of surface is called "brain terrain" as it looks like the surface of a human brain. Brain terrain lies under polygonal ground when the two are both visible in a region.[12]

-

Context picture showing origin of next picture. The location is a region of lineated valley fill. Image from HiRISE under HiWish program.

-

Open and closed-cell brain terrain, as seen by HiRISE, under HiWish program.

-

Brain terrain being formed from a thicker layer, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Arrows show the thicker unit breaking up into small cells.

Since the top, polygon layer is fairly smooth although the underlying brain terrain is irregular; it is believed that the mantle layer that contains the polygons is 10–20 meters thick.[29]

"Basketball terrain" is another expression of the surface of Mars. At certain distances it looks like a basketball’s surface. Close-up pictures have revealed it to consist of piles of rocks.[30][31] Many ideas have been advanced to explain how these piles of rocks are formed.[32][33]

Many steep surfaces in latitude bands near 40 degrees North and South contain gullies. Some of the gullies show polygons. These have been called "gullygons."[29]

-

Close-up of gully showing multiple channels and patterned ground, as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program. Locations is Phaethontis quadrangle.

-

Close-up of gullies in a crater from previous image. Image taken by HiRISE under HiWish program. Location is Mare Acidalium quadrangle.

-

Close-up of gully alcove showing "gullygons" (polygonal patterned ground near gullies), as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program Note this is an enlargement of a previous image.

-

Close-up of gully alcove showing "gullygons" (polygonal patterned ground near gullies), as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program Note this is an enlargement of a previous image.

-

Close-up of small channels in gullies in Arkhangelsky Crater in Argyre quadrangle, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program Patterned ground in the shape of polygons can be seen to the right.

Polygonal patterned ground on the Earth

On the Earth, polygonal, patterned ground is present in ice-rich ground, especially in polar regions.

-

Patterned ground on Earth.

-

Patterned ground in Alaska

-

Patterned ground in Alaska. The center is lower; hence full of water. This scene is like low-center polygons on Mars—but with water.

See also

- Casius quadrangle

- Climate of Mars

- Ismenius Lacus quadrangle

- Latitude dependent mantle

- Patterned ground

References

- ↑ http://www.diss.fu-berlin.de/diss/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/FUDISS_derivate_000000003198/16_ColdClimateLandforms-13-utopia.pdf?hosts=

- ↑ Kostama, V.-P., M. Kreslavsky, Head, J. 2006. Recent high-latitude icy mantle in the northern plains of Mars: Characteristics and ages of emplacement. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33 (L11201). doi:10.1029/2006GL025946. K>

- ↑ Malin, M., Edgett, K. 2001. Mars Global Surveyor Mars Orbiter Camera: Interplanetary cruise through primary mission. J. Geophys. Res. 106 (E10), 23429–23540.

- ↑ Milliken, R., et al. 2003. Viscous flow features on the surface of Mars: Observations from high-resolution Mars Orbiter Camera (MOC) images. J. Geophys. Res. 108 (E6). doi:10.1029/2002JE002005.

- ↑ Mangold, N. 2005. High latitude patterned grounds on Mars: Classification, distribution and climatic control. Icarus 174, 336–359.

- ↑ Kreslavsky, M., Head, J. 2000. Kilometer-scale roughness on Mars: Results from MOLA data analysis. J. Geophys. Res. 105 (E11), 26695–26712.

- ↑ Seibert, N., J. Kargel. 2001. Small-scale martian polygonal terrain: Implications for liquid surface water. Geophys. Res. Lett. 28 (5), 899–902. S

- ↑ Hecht, M. 2002. Metastability of water on Mars. Icarus 156, 373–386

- ↑ Mustard, J., et al. 2001. Evidence for recent climate change on Mars from the identification of youthful near-surface ground ice. Nature 412 (6845), 411–414.

- ↑ Kreslavsky, M.A., Head, J.W., 2002. High-latitude Recent Surface Mantle on Mars: New Results from MOLA and MOC. European Geophysical Society XXVII, Nice.

- ↑ Head, J.W., Mustard, J.F., Kreslavsky, M.A., Milliken, R.E., Marchant, D.R., 2003. Recent ice ages on Mars. Nature 426 (6968), 797–802.

- 1 2 3 Levy, J., J. Head, D. Marchant. 2009. Concentric crater fill in Utopia Planitia: History and interaction between glacial "brain terrain" and periglacial mantle processes. Icarus 202, 462–476.

- ↑ Mutch, T.A., and 24 colleagues, 1976. The surface of Mars: The view from the Viking2 lander. Science 194 (4271), 1277–1283.

- ↑ Mutch, T., et al. 1977. The geology of the Viking Lander 2 site. J. Geophys. Res. 82, 4452–4467.

- ↑ Levy, J., et al. 2009. Thermal contraction crack polygons on Mars: Classification, distribution, and climate implications from HiRISE observations. J. Geophys. Res. 114. doi:10.1029/2008JE003273.

- ↑ Washburn, A. 1973. Periglacial Processes and Environments. St. Martin’s Press, New York, pp. 1–2, 100–147.

- ↑ Mellon, M. 1997. Small-scale polygonal features on Mars: Seasonal thermal contraction cracks in permafrost. J. Geophys. Res. 102, 25,617-625,628.

- ↑ Mangold, N. 2005. High latitude patterned grounds on Mars: Classification, distribution and climatic control. Icarus 174, 336–359.

- ↑ Marchant, D., J. Head. 2007. Antarctic dry valleys: Microclimate zonation, variable geomorphic processes, and implications for assessing climate change on Mars. Icarus 192, 187–222

- ↑ Marchant, D., et al. 2002. Formation of patterned ground and sublimation till over Miocene glacier ice in Beacon valley, southern Victoria land, Antarctica. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 114, 718–730.

- ↑ Schorghofer, N., O. Aharonson. 2005. Stability and exchange of subsurface ice on Mars. J. Geophys. Res. 110 (E05). doi:10.1029/2004JE002350.

- ↑ Schorghofer, N., 2007. Dynamics of ice ages on Mars. Nature 449 (7159), 192–194

- ↑ Head, J., J. Mustard, M. Kreslavsky, R. Milliken, D. Marchant. 2003. Recent ice ages on Mars. Nature 426 (6968), 797–802.

- ↑ name= Touma J. and J. Wisdom. 1993. The Chaotic Obliquity of Mars. Science 259, 1294-1297.

- ↑ Laskar, J., A. Correia, M. Gastineau, F. Joutel, B. Levrard, and P. Robutel. 2004. Long term evolution and chaotic diffusion of the insolation quantities of Mars. Icarus 170, 343-364.

- ↑ Levy, J., J. Head, D. Marchant, D. Kowalewski. 2008. Identification of sublimation-type thermal contraction crack polygons at the proposed NASA Phoenix landing site: Implications for substrate properties and climate-driven morphological evolution. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35. doi:10.1029/2007GL032813.

- ↑ Kreslavsky, M., J. Head, J. 2002. Mars: Nature and evolution of young, latitude-dependent water-ice-rich mantle. Geophys. Res. Lett. 29, doi:10.1029/ 2002GL015392.

- ↑ Kreslavsky, M., J. Head. 2006. Modification of impact craters in the northern plains of Mars: Implications for the Amazonian climate history. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 41, 1633–1646.

- 1 2 Levy, J. et al. 2010. Thermal contraction crack polygons on Mars: A synthesis from HiRISE, Phoenix, and terrestrial analog studies. Icarus: 206, 229-252.

- ↑ http://www.uahirise.org/ESP_011816_2300

- ↑ http://www.uahirise.org/PSP_007254_2320

- ↑ http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2002GL015392/full

- ↑ Kreslavsky, M. J. Head. 2002. Mars: Nature and evolution of young latitude-dependent water-ice-rich mantle. Geophysical Research Letters.