Chord names and symbols (popular music)

Musicians use various kinds of chord names and symbols in different contexts, to represent musical chords. In most genres of popular music, including jazz, pop, and rock, a chord name and the corresponding symbol are typically composed of one or more of the following parts:

- The root note (e.g., C).

- The chord quality (e.g., minor or lowercase m, or the symbols ° or + for diminished and augmented chords; quality is usually omitted for major chords).

- The number of an interval (e.g., seventh, or 7), or less often its full name or symbol (e.g., major seventh, maj7, or M7).

- The altered fifth (e.g., sharp five, or ♯5).

- An additional interval number (e.g., add 2 or add2), in added tone chords.

For instance, the name C augmented seventh, and the corresponding symbol Caug7, or C+7, are both composed of parts 1, 2, and 3.

- More rarely, a bass note other than the root (e.g., In the key of C Major, "G/B bass", which means a G Major chord with a "B" as the bass note)

Except for the root, these parts do not refer to the notes that form the chord, but to the intervals they form with respect to the root note. For instance, Caug7 indicates a chord formed by the notes C-E-G♯-B♭. The three parts of the symbol (C, aug, and 7) refer to the root C, the augmented (fifth) interval from C to G♯, and the (minor) seventh interval from C to B♭. A set of decoding rules is applied to deduce the missing information.

Although they are used occasionally in classical music, typically in an educational setting for harmonic analysis, these names and symbols are "universally used in jazz and popular music",[1] in lead sheets, fake books, and chord charts, to specify the chords that make up the chord progression of a song or other piece of music. A typical sequence of a jazz or rock song in the key of C Major might indicate a chord progression such as "C Maj/a minor/d minor/G7".

Roles

These chord symbols are used by musicians for a number of purposes. Chord-playing instrumentalists in the rhythm section of a jazz quartet, rock or pop band or big band, such as a piano player, Hammond organist or electric guitarist use these symbols to guide their improvised performance of chord "voicings" and "fills". A rock or pop guitarist or keyboardist might literally play the chords just as indicated (e.g., the C Maj chord would be played by playing the notes "C,E,G" at the same time. In jazz, particularly for bands playing music from the 1940s Bebop era or later, a guitarist or keyboardist typically has the latitude to add in the sixth, seventh, and/or ninth, according to her "ear" and judgement. As well, part of the "jazz sound" with chord voicings is to omit the root (a task left to the bass player) and fifth. As such, a jazz guitarist might "voice" the C Maj chord with the notes "E,A,D", which are the third, sixth, and ninth of the chord. The bassist (electric bass or double bass uses the chord symbols to help her to improvise a bass line which outlines the chords, often by emphasizing the root and the other key scale tones (the third, fifth, and in a jazz context, the seventh).

The "lead instruments" in a jazz band or rock group, such as a saxophone player or lead guitarist use the chord chart to guide their improvised solo lines (or for the guitarist, her guitar solo). The instrumentalist improvising a solo may use scales that she knows work well with certain chords or chord progressions. For example, in rock and blues soloing, the pentatonic scale built on the root note is widely used to solo over straightforward chord progressions that use I, IV and V chords (in the key of C Major, these would be the chords C Maj, F Maj and G7).

Other notation systems for chords include:[2]plain staff notation, used in classical music, Roman numerals, commonly used in harmonic analysis,[3] figured bass, much used in the Baroque era, and macro symbols, sometimes used in modern musicology.

Advantages and limitations

Any chord can be denoted using staff notation, showing not only its harmonic characteristics but also its exact voicing. However, this notation, frequently used in classical music, may provide too much information, making improvisation difficult. In fact, although voicings can and do have a significant effect on the subjective musical qualities of a composition, generally these interpretations retain the central characteristics of the chord. This provides an opportunity for improvisation within a defined structure and is important to improvised music such as jazz. Other problems are that voicings for one instrument are not necessarily physically playable on another (for example, the thirteenth chord, played on piano with up to seven notes, is usually played on guitar as a 4- or 5-note voicing that is impossible to play on piano with one hand).

As a result of these limitations, popular music and jazz use a shorthand that describes the harmonic characteristics of chords. This notation is more easily expressed in plain text and in handwriting than the relatively complicated process of writing chords on a staff. It is also faster to read.

The first part of a symbol for a chord defines the root of the chord. The root of the chord is always played by one of the instruments in the ensemble (usually by a bass instrument). Failure to include the root means that the indicated chord is not played. By convention, the root alone indicates a simple major triad, i.e., the root, the major third, and the perfect fifth above the root. After this, various additional symbols are added to modify this chord. There is unfortunately no universal standard for these symbols. The most common ones are below.

This notation does not easily provide for ways of describing all chords. Some chords can be very difficult to notate, and others that exist theoretically are rarely encountered. For example, there are 6 possible permutations of triads (chords with three notes) involving minor or major thirds and perfect, augmented, or diminished fifths. However, conventionally only four are used (major, minor, augmented and diminished). There is nothing to stop a composer using the other two, but the question of what to call them is interesting. A minor third with an augmented fifth might be denoted, for example, by Am+, which would strike most musicians as odd. In fact, this turns out to be the same as F/A (see slash chords below). A major third with a diminished fifth might be shown as A(♭5).

Usually, when composers require a chord that is not easily described using this notation, they indicate the required chord in a footnote or in the header of the music.

Chord quality

Chord qualities are related with the qualities of the component intervals that define the chord (see below). The main chord qualities are:

- Major, and minor.

- Augmented, diminished, and half-diminished.

- Dominant.

Some of the symbols used for chord quality are similar to those used for interval quality:

- No symbol, or sometimes 'M' or 'Maj' (see rule 2 below) for major,

- m, or min for minor,

- aug for augmented,

- dim for diminished.

In addition, however,

- Δ is sometimes used for major,[lower-alpha 1] instead of the standard M, or maj,

- − is sometimes used for minor, instead of the standard m or min,

- +, or aug, is used for augmented (A is not used),

- o, °, dim, is used for diminished (d is not used),

- ø, or Ø is used for half diminished,

- dom may occasionally be used for dominant.

Chord qualities are sometimes omitted (see below). When specified, they appear immediately after the root note or, if the root is omitted, at the beginning of the chord name or symbol. For instance, in the symbol Cm7 (C minor seventh chord) C is the root and m is the chord quality. When the terms minor, major, augmented, diminished, or the corresponding symbols do not appear immediately after the root note, or at the beginning of the name or symbol, they should be considered interval qualities, rather than chord qualities. For instance, in Cm/M7 (minor major seventh chord), m is the chord quality and M refers to the M7 interval.

Major, minor, augmented, and diminished chords

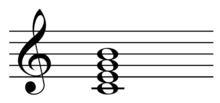

3-note chords are called triads. There are four basic triads (major, minor, augmented, diminished). They are all tertian, which means defined by the root, a third interval, and a fifth interval. Since most other chords are obtained by adding one or more notes to these triads, the name and symbol of a chord is often built by just adding an interval number to the name and symbol of a triad. For instance, a C augmented seventh chord is a C augmented triad with an extra note defined by a minor seventh interval:

C+7 = C+ + m7 augmented

chordaugmented

triadminor

interval

In this case, the quality of the additional interval is omitted. Less often, the full name or symbol of the additional interval (minor, in the example) is provided. For instance, a C augmented major seventh chord is a C augmented triad with an extra note defined by a major seventh interval:

C+M7 = C+ + M7 augmented

chordaugmented

triadmajor

interval

In both cases, the quality of the chord is the same as the quality of the basic triad it contains. This is not true for all chord qualities, as the chord qualities "half-diminished", and "dominant" refer not only to the quality of the basic triad, but also to the quality of the additional intervals.

Altered fifths

A more complex approach is sometimes used to name and denote augmented and diminished chords. An augmented triad can be viewed as a major triad in which the perfect fifth interval (spanning 7 semitones) has been substituted with an augmented fifth (8 semitones), and a diminished triad as a minor triad in which the perfect fifth has been substituted with a diminished fifth (6 semitones). In this case, the augmented triad can be named major triad sharp five, or major triad augmented fifth (M♯5, M+5, majaug5). Similarly, the diminished triad can be named minor triad flat five, or minor triad diminished fifth (m♭5, m°5, mindim5).

Again, the terminology and notation used for triads affects the terminology and notation used for larger chords, formed by four or more notes. For instance, the above-mentioned C augmented major seventh chord, is sometimes called C major seventh sharp five, or C major seventh augmented fifth. The corresponding symbol is CM7+5, CM7♯5, or Cmaj7aug5:

CM7+5 = C + M3 + A5 + M7 augmented

chordchord

rootmajor

intervalaugmented

intervalmajor

interval- (In chord symbols, the symbol A, used for augmented intervals, is typically replaced by + or ♯)

In this case, the chord is viewed as a C major seventh chord (CM7) in which the third note is an augmented fifth from root (G♯), rather than a perfect fifth from root (G). All chord names and symbols including altered fifths, i.e., augmented (♯5, +5, aug5) or diminished (♭5, °5, dim5) fifths can be interpreted in a similar way.

Rules to decode chord names and symbols

The amount of information provided in a chord name or symbol lean toward the minimum, to increase efficiency. However, it is often necessary to deduce from a chord name or symbol the component intervals that define the chord. The missing information is implied and must be deduced according to some conventional rules:

- General rule to interpret existing information about chord quality

- For triads, major or minor always refer to the third interval, while augmented and diminished always refer to the fifth. The same is true for the corresponding symbols (e.g., Cm means Cm3, and C+ means C+5). Thus, the terms third and fifth and the corresponding symbols 3 and 5 are typically omitted.

- This rule can be generalized to all kinds of chords,[lower-alpha 2] provided the above-mentioned qualities appear immediately after the root note, or at the beginning of the chord name or symbol. For instance, in the chord symbols Cm and Cm7, m refers to the interval m3, and 3 is omitted. When these qualities do not appear immediately after the root note, or at the beginning of the name or symbol, they should be considered interval qualities, rather than chord qualities. For instance, in Cm/M7 (minor-major seventh chord), m is the chord quality and refers to the m3 interval, while M refers to the M7 interval. When the number of an extra interval is specified immediately after chord quality, the quality of that interval may coincide with chord quality (e.g., CM7 = CM/M7). However, this is not always true (e.g., Cm6 = Cm/M6, C+7 = C+/m7, CM11 = CM/P11).[lower-alpha 2] See specific rules below for further details.

- General rule to deduce missing information about chord quality

- Without contrary information, a major third interval and a perfect fifth interval (major triad) are implied. For instance, a C chord is a C major triad, and the name C minor seventh (Cm7) implies a minor 3rd by rule 1, a perfect 5th by this rule, and a minor 7th by definition (see below). This rule has one exception (see the first specific rule below).

- Specific rules

- When the fifth interval is diminished, the third must be minor.[lower-alpha 3] This rule overrides rule 2. For instance, Cdim7 implies a diminished 5th by rule 1, a minor 3rd by this rule, and a diminished 7th by definition (see below).

- Names and symbols which contain only a plain interval number (e.g., “Seventh chord”) or the chord root and a number (e.g., “C seventh”, or C7) are interpreted as follows:

- If the number is 2, 4, 6, etc., the chord is a major added tone chord (e.g., C6 = CM6 = Cadd6) and contains, together with the implied major triad, an extra major 2nd, perfect 4th, or major 6th (see below). Note that 2 and 4 are sometimes also used to abbreviate suspended chords (e.g., C2 = Csus2).

- If the number is 7, 9, 11, 13, etc., the chord is dominant (e.g., C7 = Cdom7) and contains, together with the implied major triad, one or more of the following extra intervals: minor 7th, major 9th, perfect 11th, and major 13th (see Seventh chords and Extended chords below).

- If the number is 5, the chord (technically not a chord in the traditional sense, but a dyad) is a power chord. Only the root, a perfect fifth and usually an octave are played.

- For sixth chord names or symbols composed only of root, quality and number (such as "C major sixth", or "CM6"):

- M, maj, or major stands for major-major (e.g., CM6 means CM/M6),

- m, min, or minor stands for minor-major (e.g., Cm6 means Cm/M6).

- For seventh chord names or symbols composed only of root, quality and number (such as "C major seventh", or "CM7"):

- dom, or dominant stands for major-minor (e.g., Cdom7 means CM/m7),

- M, maj, or major stands for major-major (e.g., CM7 means CM/M7),

- m, min, or minor stands for minor-minor (e.g., Cm7 means Cm/m7),

- +, aug, or augmented stands for augmented-minor (e.g., C+7 means C+/m7),

- o, dim, or diminished stands for diminished-diminished (e.g., Co7 means Co/o7),

- ø, or half-diminished stands for diminished-minor (e.g., Cø7 means Co/m7).

- Other specific rules for extended and added tone chords are given below.

Examples

The table shows the application of these generic and specific rules to interpret some of the main chord symbols. The same rules apply for the analysis of chord names. A limited amount of information is explicitly provided in the chord symbol (boldface font in the column labeled "Component intervals"), and can be interpreted with rule 1. The rest is implied (plain font), and can be deduced by applying the other rules. The "Analysis of symbol parts" is performed by applying rule 1.

| Chord Symbol | Analysis of symbol parts | Component intervals | Notes | Chord name | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short | Long | Root | Third | Fifth | Added | Third | Fifth | Added | ||

| C | C | maj3 | perf5 | C-E-G | Major triad | |||||

| CM [lower-alpha 4] | Cmaj [lower-alpha 4] | C | maj | maj3 | perf5 | C-E-G | ||||

| Cm | Cmin | C | min | min3 | perf5 | C-E♭-G | Minor triad | |||

| C+ | Caug | C | aug | maj3 | aug5 | C-E-G♯ | Augmented triad | |||

| Co | Cdim | C | dim | min3 | dim5 | C-E♭-G♭ | Diminished triad | |||

| C6 | C | 6 | maj3 | perf5 | maj6 | C-E-G-A | Major sixth chord | |||

| CM6 [lower-alpha 4] | Cmaj6 [lower-alpha 4] | C | maj | 6 | maj3 | perf5 | maj6 | |||

| Cm6 | Cmin6 | C | min | 6 | min3 | perf5 | maj6 | C-E♭-G-A | Minor sixth chord | |

| C7 | Cdom7 | C | 7 | maj3 | perf5 | min7 | C-E-G-B♭ | Dominant seventh chord | ||

| CM7 | Cmaj7 | C | maj | 7 | maj3 | perf5 | maj7 | C-E-G-B | Major seventh chord | |

| Cm7 | Cmin7 | C | min | 7 | min3 | perf5 | min7 | C-E♭-G-B♭ | Minor seventh chord | |

| C+7 | Caug7 | C | aug | 7 | maj3 | aug5 | min7 | C-E-G♯-B♭ | Augmented seventh chord | |

| Co7 | Cdim7 | C | dim | 7 | min3 | dim5 | dim7 | C-E♭-G♭-B | Diminished seventh chord | |

| Cø | C | dim | min3 | dim5 | min7 | C-E♭-G♭-B♭ | Half-diminished seventh chord | |||

| Cø7 | C | dim | 7 | min3 | dim5 | min7 | ||||

| CmM7 Cm/M7 Cm(M7) |

Cminmaj7 Cmin/maj7 Cmin(maj7) |

C | min | maj7 | min3 | perf5 | maj7 | C-E♭-G-B | Minor-major seventh chord | |

For each symbol, several formatting options are available. Except for the root, all the other parts of the symbols may be either superscripted or subscripted. Sometimes, parts of the symbol may be separated by a slash, or written within parentheses. For instance:

- CM7 may be written CM7, CM7, CM7, or CM7.

- CmM7 may be written as CmM7, Cm/M7, Cm(M7), or simply CmM7.

Short and long symbols for chord quality (such as m for minor and maj for major, respectively) are sometimes both used in the same chord symbol. For instance:

- Cm(M7) may be also written Cm(maj7).

Intervals

A chord consists of two or more notes played simultaneously that are certain intervals apart with respect to the chord root. The following table shows the labels given to these intervals and the respective notes for each of the twelve keys. As explained above, chord notation provides a shorthand for intervals, not actual notes. This table provides a mapping of intervals to actual notes to play.

| Chord root | Unison | Minor second | Major second | Minor third | Major third | Perfect fourth | Tritone | Perfect fifth | Minor sixth | Major sixth | Minor seventh | Major seventh |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | C | D♭ | D | E♭ | E | F | F♯ / G♭ | G | A♭ | A | B♭ | B |

| C♯ | C♯ | D | D♯ | E | E♯ | F♯ | F |

G♯ | A | A♯ | B | B♯ |

| D♭ | D♭ | E |

E♭ | F♭ | F | G♭ | G / A |

A♭ | B |

B♭ | C♭ | C |

| D | D | E♭ | E | F | F♯ | G | G♯ / A♭ | A | B♭ | B | C | C♯ |

| D♯ | D♯ | E | E♯ | F♯ | F |

G♯ | G |

A♯ | B | B♯ | C♯ | C |

| E♭ | E♭ | F♭ | F | G♭ | G | A♭ | A / B |

B♭ | C♭ | C | D♭ | D |

| E | E | F | F♯ | G | G♯ | A | A♯ / B♭ | B | C | C♯ | D | D♯ |

| F | F | G♭ | G | A♭ | A | B♭ | B / C♭ | C | D♭ | D | E♭ | E |

| F♯ | F♯ | G | G♯ | A | A♯ | B | B♯ / C | C♯ | D | D♯ | E | E♯ |

| G♭ | G♭ | A |

A♭ | B |

B♭ | C♭ | C / D |

D♭ | E |

E♭ | F♭ | F |

| G | G | A♭ | A | B♭ | B | C | C♯ / D♭ | D | E♭ | E | F | F♯ |

| G♯ | G♯ | A | A♯ | B | B♯ | C♯ | C |

D♯ | E | E♯ | F♯ | F |

| A♭ | A♭ | B |

B♭ | C♭ | C | D♭ | D / E |

E♭ | F♭ | F | G♭ | G |

| A | A | B♭ | B | C | C♯ | D | D♯ / E♭ | E | F | F♯ | G | G♯ |

| A♯ | A♯ | B | B♯ | C♯ | C |

D♯ | D |

E♯ | F♯ | F |

G♯ | G |

| B♭ | B♭ | C♭ | C | D♭ | D | E♭ | E / F♭ | F | G♭ | G | A♭ | A |

| B | B | C | C♯ | D | D♯ | E | E♯ / F | F♯ | G | G♯ | A | A♯ |

Triads

As earlier suggested, the root written alone indicates a simple major triad. It consists of the root, the major third, and the perfect fifth above the root. Minor triads are the same as major triads, but with the third lowered by a half step. Augmented triads are the same as a major triad, but with an augmented fifth instead of a perfect fifth. Diminished triads are similar to minor triads, but with a diminished fifth instead of a perfect fifth (the minor third is retained).

The table below shows names, symbols and definition for the four kinds of triads (using C as root).

| Name | Symbols | Definitions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short | Long | Altered fifth |

Component intervals | Integers | Notes | ||

| Third | Fifth | ||||||

| Major triad | C CM [lower-alpha 4] CΔ [lower-alpha 1] | Cmaj [lower-alpha 4] | major | perfect | {0, 4, 7} | C-E-G | |

| Minor triad | Cm C− | Cmin | minor | perfect | {0, 3, 7} | C-E♭-G | |

| Augmented triad (major triad sharp five) | C+ | Caug | CM♯5 CM+5 | major | augmented | {0, 4, 8} | C-E-G♯ |

| Diminished triad (minor triad flat five) | C° | Cdim | Cm♭5 Cm°5 | minor | diminished | {0, 3, 6} | C-E♭-G♭ |

Seventh chords

A seventh chord is a triad with an added note, which is either a major seventh above the root, a minor seventh above the root (flatted 7th), or a diminished seventh above the root (double flatted 7th). Note that the diminished seventh note is enharmonically equivalent to the major sixth above the root of the chord. When not otherwise specified, the name "seventh chord" may more specifically refer to a major triad with an added minor seventh (a dominant seventh chord).

The table below shows names, symbols, and definitions for the various kinds of seventh chords (using C as root).

| Name | Symbols | Definitions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short | Long | Altered fifth |

Component intervals | Integers | Notes | |||

| Third | Fifth | Seventh | ||||||

| Seventh (dominant seventh) | C7 | Cdom7 | major | perfect | minor | {0, 4, 7, 10} | C-E-G-B♭ | |

| Major seventh | CM7 CMa7 C j7 CΔ7 CΔ [lower-alpha 1] | Cmaj7 | major | perfect | major | {0, 4, 7, 11} | C-E-G-B | |

| Minor-major seventh | CmM7 Cm♯7 C−M7 C−Δ7 C−Δ | Cminmaj7 | minor | perfect | major | {0, 3, 7, 11} | C-E♭-G-B | |

| Minor seventh | Cm7 C-7 | Cmin7 | minor | perfect | minor | {0, 3, 7, 10} | C-E♭-G-B♭ | |

| Augmented-major seventh (major seventh sharp five) | C+M7 C+Δ | Caugmaj7 | CM7♯5 / CM7+5 CΔ♯5 / CΔ+5 | major | augmented | major | {0, 4, 8, 11} | C-E-G♯-B |

| Augmented seventh (dominant seventh sharp five) | C+7 | Caug7 | C7♯5 / C7+5 | major | augmented | minor | {0, 4, 8, 10} | C-E-G♯-B♭ |

| Half-diminished seventh (minor seventh flat five) | CØ / CØ7 Cø / Cø7 | Cmin7dim5 | Cm7♭5 / Cm7°5 C−7♭5 / C−7°5 | minor | diminished | minor | {0, 3, 6, 10} | C-E♭-G♭-B♭ |

| Diminished seventh | Co7 C°7 | Cdim7 | minor | diminished | diminished | {0, 3, 6, 9} | C-E♭-G♭-B | |

| Seventh flat five (dominant seventh flat five) | C7♭5 | Cdom7dim5 | major | diminished | minor | {0, 4, 6, 10} | C-E-G♭-B♭ | |

For each symbol, several formatting options are available. See Examples above for further details.

Some 7th chords can be considered as triad chords with alternate bass. For instance,

- Cm7 = C-E♭-G-B♭ = E♭/C

- Cmaj7 = C-E-G-B = Em/C

Extended chords

Extended chords add further notes onto 7th chords. Of the 7 notes in the major scale, a seventh chord uses only 4. The other 3 notes can be added in any combination; however, just as with the triads and seventh chords, notes are most commonly stacked – a seventh implies that there is a fifth and a third and a root. In practice, especially in jazz, certain notes can be omitted without changing the quality of the chord.

The 9th, 11th and 13th chords are known as extended tertian chords. As the scale repeats for every seven notes in the scale, these notes are enharmonically equivalent to the 2nd, 4th, and 6th – except they are more than an octave above the root. However, this does not mean that they must be played in the higher octave. Although changing the octave of certain notes in a chord (within reason) does change the way the chord sounds, it does not change the essential characteristics or tendency of it. Accordingly, using 9th, 11th and 13th in chord notation implies that the chord is an extended tertian chord rather than an added chord (see Added Chords below).

9ths

9th chords are built by adding a 9th from the root to a seventh chord. A 9th chord includes the 7th. Without the 7th, the chord is not an extended chord, but becomes an added tone chord—in this case, an add 9. 9ths can be added to any chord, but are most commonly seen with major, dominant, and minor sevenths.

The most commonly omitted note for a voicing is the perfect 5th.

The table below shows names, symbols, and definitions for the various kinds of ninth chords (using C as root)

| Name | Symbol | Quality of added 9th |

Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short | Long | |||

| (Major) 9th | CM9 / CΔ9 | Cmaj9 | Major | C-E-G-B-D |

| Dominant 9th | C9 | Cdom9 | Major | C-E-G-B♭-D |

| Minor Major 9th | CmM9 / C−M9 | Cminmaj9 | Major | C-E♭-G-B-D |

| Minor Dominant 9th | Cm9 / C−9 | Cmin9 | Major | C-E♭-G-B♭-D |

| Augmented Major 9th | C+M9 | Caugmaj9 | Major | C-E-G♯-B-D |

| Augmented Dominant 9th | C+9 / C9♯5 | Caug9 | Major | C-E-G♯-B♭-D |

| Half-Diminished 9th | CØ9 | Major | C-E♭-G♭-B♭-D | |

| Half-Diminished Minor 9th | CØ♭9 | Minor | C-E♭-G♭-B♭-D♭ | |

| Diminished 9th | C°9 | Cdim9 | Major | C-E♭-G♭-B |

| Diminished Minor 9th | C°♭9 | Cdim♭9 | Minor | C-E♭-G♭-B |

11ths

These are theoretically 9th chords with the 11th (4th) note in the scale added. However, it is common to leave certain notes out. The major 3rd is often omitted because of a strong dissonance with the 11th (4th), therefore called an avoid note. Omission of the 3rd reduces an 11th chord to the corresponding 9sus4 (suspended 9th chord; Aiken 2004, p. 104). Similarly, omission of the 3rd as well as 5th in C11 results in a major chord with alternate base B♭/C, which is characteristic in soul and gospel music. For instance:

C11 without 3rd = C-(E)-G-B♭-D-F ≈ C-F-G-B♭-D = C9sus4

C11 without 3rd and 5th = C-(E)-(G)-B♭-D-F ≈ C-F-B♭-D = B♭/C

If the 9th is omitted, the chord is no longer an extended chord, but an added tone chord (see below). Without the 3rd, this added tone chord becomes a 7sus4 (suspended 7th chord). For instance:

C11 without 9th = C7add11 = C-E-G-B♭-(D)-F

C7add11 without 3rd = C-(E)-G-B♭-(D)-F ≈ C-F-G-B♭ = C7sus4

The table below shows names, symbols, and definitions for the various kinds of eleventh chords (using C as root)

| Name | Symbol | Quality of added 11th |

Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short | Long | |||

| 11th (dominant 11th) | C11 | Cdom11 | Perfect | C-E-G-B♭-D-F |

| Major 11th | CM11 | Cmaj11 | Perfect | C-E-G-B-D-F |

| Minor-Major 11th | CmM11 / C−M11 | Cminmaj11 | Perfect | C-E♭-G-B-D-F |

| Minor 11th | Cm11 / C−11 | Cmin11 | Perfect | C-E♭-G-B♭-D-F |

| Augmented-Major 11th | C+M11 | Caugmaj11 | Perfect | C-E-G♯-B-D-F |

| Augmented 11th | C+11 / C11♯5 | Caug11 | Perfect | C-E-G♯-B♭-D-F |

| Half-Diminished 11th | CØ11 | Perfect | C-E♭-G♭-B♭-D♭-F | |

| Diminished 11th | C°11 | Cdim11 | Diminished | C-E♭-G♭-B |

Alterations from the natural diatonic chords can be specified as C9♯11 ... etc. Omission of the 5th in a sharpened 11th chord reduces its sound to a flat-five chord. (Aiken 2004, p. 94):

C9♯11 = C-E-(G)-B♭-D-F♯ ≈ C-E-G♭-B♭-D = C9♭5

13ths

These are theoretically 11th chords with the 13th (or 6th) note in the scale added. In other words, theoretically they are formed by all the seven notes of a diatonic scale at once. Again, it is common to leave certain notes out. After the 5th, the most commonly omitted note is the troublesome 11th (4th). The 9th (2nd) can also be omitted. A very common voicing on guitar for a 13th chord is just the root, 3rd, 7th and 13th (or 6th). For example: C-E-(G)-B♭-(D)-(F)-A, or C-E-(G)-A-B♭-(D)-(F). On the piano, this is usually voiced C-B♭-E-A.

The table below shows names, symbols, and definitions for some thirteenth chords (using C as root)

| Name | Symbol | Quality of added 13th |

Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short | Long | |||

| Major 13th | CM13 / CΔ13 | Cmaj13 | Major | C-E-G-B-D-F-A |

| Dominant 13th | C13 | Cdom13 | Major | C-E-G-B♭-D-F-A |

| Minor Major 13th | CmM13 / C−M13 | Cminmaj13 | Major | C-E♭-G-B-D-F-A |

| Minor Dominant 13th | Cm13 / C−13 | Cmin13 | Major | C-E♭-G-B♭-D-F-A |

| Augmented Major 13th | C+M13 | Caugmaj13 | Major | C-E-G♯-B-D-F-A |

| Augmented Dominant 13th | C+13 / C13♯5 | Caug13 | Major | C-E-G♯-B♭-D-F-A |

| Half-Diminished 13th | CØ13 | Major | C-E♭-G♭-B♭-D-F-A | |

Alterations from the natural diatonic chords can be specified as C11♭13 ... etc.

Added tone chords

An important characteristic of jazz is the extensive use of sevenths. The combination of 9th (2nd), 11th (4th) and 13th (6th) notes with 7ths in a chord give jazz chord voicing their distinctive sound. However the use of these notes is not exclusive to the jazz genre; in fact they are very commonly used in folk, classical and popular music generally. Without the 7th, these chords lose their jazzy feel, but can still be very complex. These chords are called added tone chords because they are basic triads with notes added. They can be described as having a more open sound than extended chords. Notation must provide some way of showing that a chord is an added tone chord as opposed to extended. There are two ways this is shown generally, and it is very common to see both methods on the same score. One way is to simply use the word 'add', for example:

- Cadd9

The second way is to use 2 instead of 9, implying that it is not a 7th chord for instance:

- C2

Note that in this way we potentially get other ways of showing a 9th chord:

- C7add9

- C7add2

- C7/9

Generally however the above is shown as simply C9, which implies a 7th in the chord. Added tone chord notation is useful with 7th chords to indicate partial extended chords. For example:

- C7add13

This would indicate that the 13th is added to the 7th, but without the 9th and 11th.

The use of 2, 4 and 6 as opposed to 9, 11 and 13 indicates that the chord does not include a 7th unless specifically specified. However, it does not mean that these notes must be played within an octave of the root, nor the extended notes in 7th chords should be played outside of the octave, although it is commonly the case. 6 is particularly common in a minor sixth chord (also known as minor/major sixth chord, as the 6 refers to a major sixth interval).

It is possible to have added tone chords with more than one added note. The most commonly encountered of these are 6/9 chords, which are basic triads with the 6th and 2nd notes of the scale added. These can be confusing because of the use of 9, yet the chord does not include the 7th. A good rule of thumb is that if any added note is less than 7, then no 7th is implied, even if there are some notes shown as greater than 7.

Similarly, even numbers such as 8, 10 and 12 can be added. However, these double the main triad, and as such are fairly rare. 10 tends to be the most common; it can be used both in suspended chords and (with an accidental) in major or minor chords to produce a major-minor clash (e.g., C7(♭10) indicating the Hendrix chord of C-E♭-E-G-B♭). However, because of enharmonics, such chords can more easily, and perhaps more intuitively, be represented by ♯2 (or ♯9) for a minor over a major or ♭4 for a major over a minor. In any other case, an 8, 10 or 12 simply indicates the respective note from the triad doubled up one octave.

Suspended chords

A suspended chord is a triad where the 3rd is replaced by another note. In practice the 3rd is replaced either by the 4th or the 2nd. These chords "desire" to resolve into a normal triad. Suspended chords are notated with the symbols "sus4" or "sus2". Where "sus" is found on its own, the suspended fourth chord is implied. This can be combined with any other notation. So for example:

- C9sus4

This chord is an extended 9th chord with the 3rd replaced by the 4th (C-F-G-B♭-D). However, the major third can be added as a tension above the 4th to "colorize" the chord (C-F-G-B♭-D-E). A sus4 chord with the added major third (sometimes called a major 10th) can also be quartally voiced as C-F-B♭-E.

Power "chords"

Though power chords are not true chords per se, they are still expressed using a version of chord notation. Most commonly, power chords (e.g., C-G-C) are expressed using a "5" (e.g., C5). Power chords are also referred to as fifth chords, indeterminate chords or neutral chords (though the term "neutral chord," when expressed with an n (e.g., Cn), is also used to describe a pair of stacked neutral thirds, e.g., C-E![]() -G, which requires a quarter tone or similarly sized microtone; or the mixed third chord), since they are inherently neither major nor minor; generally, a power chord refers to a specific doubled-root, three-note voicing of a fifth chord.

-G, which requires a quarter tone or similarly sized microtone; or the mixed third chord), since they are inherently neither major nor minor; generally, a power chord refers to a specific doubled-root, three-note voicing of a fifth chord.

To represent an extended neutral chord, e.g., a seventh (C-G-B♭), the chord is expressed as its corresponding extended chord notation with the addition of the words "no3rd," "no3" or the like. The aforementioned chord, for instance, would be indicated C7no3.

Chords containing quarter tones

While not a common practice, the methods for naming chord names and symbols can be adapted to naming chords that contain quarter tones.

Neutral chords

Neutral chords are chords built entirely by stacking neutral thirds (the interval between a major and minor third). While the neutral triad can sound like major or minor depending on context, it can also be thought of as a chord quality in its own right. An example of the neutral triad would be C-E![]() -G where the E

-G where the E![]() exists halfway between E♭ and E♮. The neutral triad is quite rare and is more commonly seen as the neutral seventh chord such as C E

exists halfway between E♭ and E♮. The neutral triad is quite rare and is more commonly seen as the neutral seventh chord such as C E![]() G B

G B![]() . These chords are composed of two fifths being a neutral third apart. The chord symbol can be written with a lowercase "n" or "neut" following the root such as Cn7. Neutral chords can also be extended to higher degrees such as ninths and elevenths. While there is no universally accepted series of notes for larger neutral chords, it makes sense to consider that higher extensions to the chord would be built in the same manner that the seventh chord is, by a series of neutral thirds.

. These chords are composed of two fifths being a neutral third apart. The chord symbol can be written with a lowercase "n" or "neut" following the root such as Cn7. Neutral chords can also be extended to higher degrees such as ninths and elevenths. While there is no universally accepted series of notes for larger neutral chords, it makes sense to consider that higher extensions to the chord would be built in the same manner that the seventh chord is, by a series of neutral thirds.

Supermajor and subminor

Supermajor chords are major triads that have the third raised a quarter tone higher than normal. Such a triad is arguably either an altered version of a suspended chord or a unique triad in its own right. Subminor chords are minor triads that have the third lowered by a quarter tone. An example of a supermajor triad would be C-E![]() -G, in which E

-G, in which E![]() exists halfway between E and F. An example of a subminor triad would be C-E

exists halfway between E and F. An example of a subminor triad would be C-E![]() -G in which E

-G in which E![]() exists halfway between D and E♭. Supermajor triads can be written with "sup" or a capital "S" following the root while subminor can be written with "sub" or a small "s". The previous examples would therefore be Csup or CS, and Csub or Cs. Because triads such as these rarely appear in musical context, they are considered theoretical.

exists halfway between D and E♭. Supermajor triads can be written with "sup" or a capital "S" following the root while subminor can be written with "sub" or a small "s". The previous examples would therefore be Csup or CS, and Csub or Cs. Because triads such as these rarely appear in musical context, they are considered theoretical.

In addition, sevenths can be theoretically created as well based on keeping the relationship of a chord having two perfect fifths the same. While a C major seventh chord would have a major third and major seventh, Csup7 would contain a supermajor third (E![]() ) and a supermajor seventh (B

) and a supermajor seventh (B![]() ). Csub7 would contain a subminor third (E

). Csub7 would contain a subminor third (E![]() ) and a subminor seventh (B

) and a subminor seventh (B![]() ). Arguably, higher extensions could be used as well, producing chord names such as Csup11 or Csub13♭9.

). Arguably, higher extensions could be used as well, producing chord names such as Csup11 or Csub13♭9.

Inversions

In addition to all of the ways of building chords (listed above), a chord may be inverted. Inverting a chord refers to playing a chord, but with a note other than the root as the lowest note of the chord. Take, for example, the C major and the C dominant seventh chords. Refer to the tables below for a list of inversions.

| Root position | First inversion | Second inversion | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Notes | C – E – G | E – G – C | G – C – E |

| Short notation | C | C/E | C/G |

| Root position | Third inversion | |

|---|---|---|

| Notes | C – E – G – B♭ | B♭ – C – E – G |

| Short notation | C7 | C7/B♭ |

The notation C/E indicates a C major chord, but with an E in the bass. Likewise the notation C/G indicates that a C major chord is played with a G in the bass.

See figured bass for alternate method of notating specific notes in the bass.

Hybrid chords

Upper structures

Those are notated in a similar manner to inversions, except that the bass note is not necessarily a chord tone. Examples:

- C/A♭ (A♭ C E G), equivalent to A♭Δ7♯5;

- C♯/E (E G♯ C♯ F);

- Am/D (D A C E).

Chord notation in jazz usually leaves a certain amount of freedom to the player as for voicing chords, also adding tensions at the player's discretion. Therefore, upper structures are most useful when the composer wants musicians to play a specific tension array. Example:

4

4 C♯/E | C/A E♭/A | D♭/E♭ G♭Δ7♯5/A♭ | E♭add2/D♭ D♭7♯9/G | Am7/C ||

produces a certain coloration of the following chord progression:

4

4 E7 | Am7 A7 | E♭m7 A♭7 | D♭ G7 | C ||

These are also commonly referred as "slash chords." A slash chord is simply a chord placed on top of a different bass note; for example:

- D/F♯ is a D chord with F♯ in the bass;

- A/C♯ is an A chord with C♯ in the bass.

Slash chords generally do not indicate a simple inversion (which is usually left to the player's discretion anyway), especially considering that the specified bass note may not be part of the chord to play on top. The bass note may be played instead of or in addition to the chord's usual root note, though the root note, when played, is likely to be played only in a higher octave to avoid "colliding" with the new bass note.

Polychords

Polychords, as the name suggests, are combinations of two or more chords. The most commonly found form of a polychord is a bi-chord (two chords played simultaneously) and is written as follows: upper chord/lower chord (example: B/C (C E G B D♯ F♯)). In case a very specific voicing is needed, the individual chords can be written in their desired inversions, for example: E♭m/G♭/Cdrop2 (C G E G♭ B♭ E♭).

Other symbols

The right slash / or diagonal line written above the staff where chord symbols occur is used to indicate a beat during which the most recent chord symbol is understood to continue. It is used to help make uneven harmonic rhythms more readable. For example, if written above a measure of standard time, "C / F G" would mean that the C chord symbol lasts two beats while F and G last one beat each. The slash is separated from the surrounding chord symbols so as not to be confused with the chord-over-a-bass-note notation that also uses a slash.

For chord abbreviations, the right slash indicates the bass note if other than the root. It is usually written with the complete chord name, and, after the slash symbol, the desired bass note. For example, the symbol C/G would mean that the chord to play is a C major triad with a G as the bass note, leading to the following notes: G C E (commonly known as the 2nd inversion C major triad).

A right slash surrounded by two dots 𝄎 reminiscent of a percent sign % [illustration needed] in an otherwise empty measure tells the musician to repeat chord or chords of the previous measure. It can be reused over many consecutive measures. It simplifies the job of both the reader (who can quickly scan ahead to the next chord change) and the copyist (who doesn't need to repeat every chord symbol).

The chord notation N.C. is indicates that the musician should play no chord. The duration of this symbol follows the same rules as a regular chord symbol.

Summary

Since the rules to decode chord notation are complex, a short article would not be sufficient to describe them clearly and exhaustively. As a consequence, this article is relatively long and not easy to decipher at a glance. This section is included as a brief summary of one of the notations described, aimed more at the performer's perspective, rather than that of the composer or theorist.

As shown above, the symbol Cminmaj13 indicates a chord whose root is C, with each of the odd-numbered intervals, up to the one indicated (13th in this case) placed above it. Namely, the chord is defined by the following odd-numbered intervals:

- Minor third (C-E♭)

- Perfect fifth (C-G)

- Major seventh (C-B)

- Major ninth (C-D)

- Perfect eleventh (C-F)

- Major thirteenth (C-A)

Notice that all the intervals are major or perfect, except for the third, which is minor, as specified by min in the symbol. By comparing other chord symbols to Cminmaj13, with the following set of rules it is possible to decode several other chord symbols:

- When the interval name (maj13) is omitted, it is understood to be a 5th, which implies that the chord is a triad.

- When the interval quality (maj) is omitted, it flattens the 7th (if present) (from major to minor)

- When the chord quality (min) is omitted, the 3rd is assumed to be major

- When the chord quality is min (as in the example above), the 3rd is flattened (from major to minor)

- When the chord quality is aug, the 5th is sharpened (from perfect to augmented)

- When the chord quality is dim, each of the intervals is flattened

- When the chord quality is sus or sus4, the 3rd is sharpened (from major to augmented, equivalent to a perfect 4th)

- When the chord quality is sus2 the 3rd is double-flattened (from major to diminished, equivalent to a major 2nd)

For instance, Cdim9 indicates a chord whose root is C, with a flattened 3rd, a flattened 5th, a double-flattened 7th (flattened once by the presence of dim, and flattened again by the omission of the maj) and a flattened 9th.

When a small even number is used as the main interval: 2 is equivalent to 9, 4 is equivalent to 11, and 6 is equivalent to 13; but with the omission of the 7th, possibly implied in each case; and when the number is explicitly stated as a 5, it implies the omission of the 3rd.

In the vast majority of cases, though, none of this complexity is involved. A typical piece of music might stipulate chords like C, F, Amin, and G7, giving (according to the summary above) two major triads, a minor triad, and an extended chord of four notes.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 The symbol Δ is ambiguous, as it is used by some as a synonym for M (e.g., CΔ=CM and CΔ7=CM7), and by others as a synonym of M7 (e.g., CΔ=CM7).

- 1 2 General rule 1 achieves consistency in the interpretation of symbols such as CM7, Cm6, and C+7. Some musicians legitimately prefer to think that, in CM7, M refers to the seventh, rather than to the third. This alternative approach is legitimate, as both the third and seventh are major, yet it is inconsistent, as a similar interpretation is impossible for Cm6 and C+7 (in Cm6, m cannot possibly refer to the sixth, which is major by definition, and in C+7, + cannot refer to the seventh, which is minor). Both approaches reveal only one of the intervals (M3 or M7), and require other rules to complete the task. Whatever is the decoding method, the result is the same (e.g., CM7 is always conventionally decoded as C-E-G-B, implying M3, P5, M7). The advantage of rule 1 is that it has no exceptions, which makes it the simplest possible approach to decode chord quality.

According to the two approaches, some may format CM7 as CM7 (general rule 1: M refers to M3), and others as CM7 (alternative approach: M refers to M7). Fortunately, even CM7 becomes compatible with rule 1 if it is considered an abbreviation of CMM7, in which the first M is omitted. The omitted M is the quality of the third, and is deduced according to rule 2 (see above), consistently with the interpretation of the plain symbol C, which by the same rule stands for CM. - ↑ All triads are tertian chords (chords defined by sequences of thirds), and a major third would produce in this case a non-tertian chord. Namely, the diminished fifth spans 6 semitones from root, thus it may be decomposed into a sequence of two minor thirds, each spanning 3 semitones (m3 + m3), compatible with the definition of tertian chord. If a major third were used (4 semitones), this would entail a sequence containing a major second (M3 + M2 = 4 + 2 semitones = 6 semitones), which would not meet the definition of tertian chord.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Rarely used symbol. A shorter symbol exists, and is used more frequently.

Sources

- ↑ Benward & Saker (2003). Music: In Theory and Practice, Vol. I, p. 78. Seventh Edition. ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0.

- ↑ Benward & Saker (2003). Music: In Theory and Practice, Vol. I, p. 77. Seventh Edition. ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0.

- ↑ Schoenberg, Arnold (1983). Structural Functions of Harmony, p.1-2. Faber and Faber. 0393004783

Further reading

- Aikin, Jim (2004). Chords & Harmony. San Francisco: Backbeat Books. ISBN 0-87930-798-6

- Carl Brandt and Clinton Roemer (1976). Standardized Chord Symbol Notation. Roevick Music Co. ISBN 978-0961268428. Cited in Benward & Saker (2003), p. 76.