Price discrimination

Price discrimination is a microeconomic pricing strategy where identical or largely similar goods or services are transacted at different prices by the same provider in different markets.[1][2][3] Price differentiation is distinguished from product differentiation by the more substantial difference in production cost for the differently priced products involved in the latter strategy.[3] Price differentiation essentially relies on the variation in the customers' willingness to pay[2][3] and in the elasticity of their demand.

The term differential pricing is also used to describe the practice of charging different prices to different buyers for the same quality and quantity of a product,[4] but it can also refer to a combination of price differentiation and product differentiation.[3] Other terms used to refer to price discrimination include equity pricing, preferential pricing,[5] and tiered pricing.[6] Within the broader domain of price differentiation, a commonly accepted classification dating to the 1920s is:[7][8]

- Personalized pricing (or first-degree price differentiation) — selling to each customer at a different price; this is also called one-to-one marketing.[7] The optimal incarnation of this is called perfect price discrimination and maximizes the price that each customer is willing to pay.[7]

- Product versioning[2][9] or simply versioning (or second-degree price differentiation) — offering a product line[7] by creating slightly different products for the purpose of price differentiation,[2][9] i.e. a vertical product line.[10] Another name given to versioning is menu pricing.[8][11]

- Group pricing (or third-degree price differentiation) — dividing the market in segments and charging the same price for everyone in each segment[7][12] This is essentially a heuristic approximation that simplifies the problem in face of the difficulties with personalized pricing.[8][13] Typical examples include student discounts[12] and seniors' discounts.

Theoretical basis

In a theoretical market with perfect information, perfect substitutes, and no transaction costs or prohibition on secondary exchange (or re-selling) to prevent arbitrage, price discrimination can only be a feature of monopolistic and oligopolistic markets,[14] where market power can be exercised. Otherwise, the moment the seller tries to sell the same good at different prices, the buyer at the lower price can arbitrage by selling to the consumer buying at the higher price but with a tiny discount. However, product heterogeneity, market frictions or high fixed costs (which make marginal-cost pricing unsustainable in the long run) can allow for some degree of differential pricing to different consumers, even in fully competitive retail or industrial markets.

The effects of price discrimination on social efficiency are unclear. Output can be expanded when price discrimination is very efficient. Even if output remains constant, price discrimination can reduce efficiency by misallocating output among consumers.

Price discrimination requires market segmentation and some means to discourage discount customers from becoming resellers and, by extension, competitors. This usually entails using one or more means of preventing any resale: keeping the different price groups separate, making price comparisons difficult, or restricting pricing information. The boundary set up by the marketer to keep segments separate is referred to as a rate fence. Price discrimination is thus very common in services where resale is not possible; an example is student discounts at museums: In theory, students, for their condition as students, may get lower prices than the rest of the population for a certain product or service, and later will not become resellers, since what they received, may only be used or consumed by them. Another example of price discrimination is intellectual property, enforced by law and by technology. In the market for DVDs, laws require DVD players to be designed and produced with hardware or software that prevents inexpensive copying or playing of content purchased legally elsewhere in the world at a lower price. In the US the Digital Millennium Copyright Act has provisions to outlaw circumventing of such devices to protect the enhanced monopoly profits that copyright holders can obtain from price discrimination against higher price market segments.

Price discrimination can also be seen where the requirement that goods be identical is relaxed. For example, so-called "premium products" (including relatively simple products, such as cappuccino compared to regular coffee with cream) have a price differential that is not explained by the cost of production. Some economists have argued that this is a form of price discrimination exercised by providing a means for consumers to reveal their willingness to pay.

Types

First degree

Exercising First degree (or Perfect/Primary) price discrimination requires the monopoly seller of a good or service to know the absolute maximum price (or reservation price) that every consumer is willing to pay. By knowing the reservation price, the seller is able to sell the good or service to each consumer at the maximum price he is willing to pay, and thus transform the consumer surplus into revenues. So the profit is equal to the sum of consumer surplus and producer surplus. The marginal consumer is the one whose reservation price equals to the marginal cost of the product. The seller produces more of his product than he would to achieve monopoly profits with no price discrimination, which means that there is no deadweight loss. Examples of where this might be observed are in markets where consumers bid for tenders, though, in this case, the practice of collusive tendering could reduce the market efficiency.[15]

Second degree

In second degree price discrimination, price varies according to quantity demanded. Larger quantities are available at a lower unit price. This is particularly widespread in sales to industrial customers, where bulk buyers enjoy higher discounts.[16]

Additionally to second degree price discrimination, sellers are not able to differentiate between different types of consumers. Thus, the suppliers will provide incentives for the consumers to differentiate themselves according to preference, which is done by quantity "discounts", or non-linear pricing. This allows the supplier to set different prices to the different groups and capture a larger portion of the total market surplus.

In reality, different pricing may apply to differences in product quality as well as quantity. For example, airlines often offer multiple classes of seats on flights, such as first class and economy class, with the first class passengers receiving wine, beer and spirits with their ticket and the economy passengers offered only juice, pop and water. This is a way to differentiate consumers based on preference, and therefore allows the airline to capture more consumer's surplus.

Third degree

Third degree price discrimination, means charging a different price to different consumer groups. For example, rail and tube (subway) travelers can be subdivided into commuter and casual travelers, and cinema goers can be subdivided into adults and children, which some theatres also offering discounts to full-time students and seniors. Splitting the market into peak and off peak use of a service is very common and occurs with gas, electricity, and telephone supply, as well as gym membership and parking charges. Some parking lots charge less for "early bird" customers who arrive at the parking lot before a certain time.

Combination

These types are not mutually exclusive. Thus a company may vary pricing by location, but then offer bulk discounts as well. Airlines use several different types of price discrimination, including:

- Bulk discounts to wholesalers, consolidators, and tour operators

- Incentive discounts for higher sales volumes to travel agents and corporate buyers

- Seasonal discounts, incentive discounts, and even general prices that vary by location. The price of a flight from say, Singapore to Beijing can vary widely if one buys the ticket in Singapore compared to Beijing (or New York or Tokyo or elsewhere).

- Discounted tickets requiring advance purchase and/or Saturday stays. Both restrictions have the effect of excluding business travelers, who typically travel during the workweek and arrange trips on shorter notice.

- First degree price discrimination based on customer. Hotel or car rental firms may quote higher prices to their loyalty program's top tier members than to the general public.

Modern taxonomy

The first/second/third degree taxonomy of price discrimination is due to Pigou (Economics of Welfare, 4th edition, 1932). See, e.g., modern taxonomy of price discrimination. However, these categories are not mutually exclusive or exhaustive. Ivan Png (Managerial Economics, 2nd edition, 2002) suggests an alternative taxonomy:

- Complete discrimination -- where each user purchases up to the point where the user's marginal benefit equals the marginal cost of the item;

- Direct segmentation -- where the seller can condition price on some attribute (like age or gender) that directly segments the buyers;

- Indirect segmentation -- where the seller relies on some proxy (e.g., package size, usage quantity, coupon) to structure a choice that indirectly segments the buyers.

The hierarchy—complete/direct/indirect—is in decreasing order of

- profitability and

- information requirement.

Complete price discrimination is most profitable, and requires the seller to have the most information about buyers. Indirect segmentation is least profitable, and requires the seller to have the least information about buyers.

Two part tariff

The two-part tariff is another form of price discrimination where the producer charges an initial fee then a secondary fee for the use of the product. An example of this is razors, you pay an initial cost for the razor and then pay for the replacement blades. This pricing strategy works because it shifts the demand curve to the right: since you have already paid for the initial blade holder you will buy the blades which are now cheaper than buying a disposable razor.

Explanation

The purpose of price discrimination is generally to capture the market's consumer surplus. This surplus arises because, in a market with a single clearing price, some customers (the very low price elasticity segment) would have been prepared to pay more than the single market price. Price discrimination transfers some of this surplus from the consumer to the producer/marketer. Strictly, a consumer surplus need not exist, for example where some below-cost selling is beneficial due to fixed costs or economies of scale. An example is a high-speed internet connection shared by two consumers in a single building; if one is willing to pay less than half the cost, and the other willing to make up the rest but not to pay the entire cost, then price discrimination is necessary for the purchase to take place.

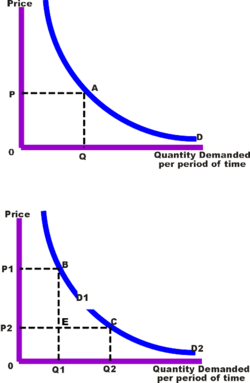

It can be proved mathematically that a firm facing a downward sloping demand curve that is convex to the origin will always obtain higher revenues under price discrimination than under a single price strategy. This can also be shown geometrically.

In the top diagram, a single price (P) is available to all customers. The amount of revenue is represented by area P, A, Q, O. The consumer surplus is the area above line segment P, A but below the demand curve (D).

With price discrimination, (the bottom diagram), the demand curve is divided into two segments (D1 and D2). A higher price (P1) is charged to the low elasticity segment, and a lower price (P2) is charged to the high elasticity segment. The total revenue from the first segment is equal to the area P1,B, Q1,O. The total revenue from the second segment is equal to the area E, C,Q2,Q1. The sum of these areas will always be greater than the area without discrimination assuming the demand curve resembles a rectangular hyperbola with unitary elasticity. The more prices that are introduced, the greater the sum of the revenue areas, and the more of the consumer surplus is captured by the producer.

Note that the above requires both first and second degree price discrimination: the right segment corresponds partly to different people than the left segment, partly to the same people, willing to buy more if the product is cheaper.

It is very useful for the price discriminator to determine the optimum prices in each market segment. This is done in the next diagram where each segment is considered as a separate market with its own demand curve. As usual, the profit maximizing output (Qt) is determined by the intersection of the marginal cost curve (MC) with the marginal revenue curve for the total market (MRt).

.svg.png)

The firm decides what amount of the total output to sell in each market by looking at the intersection of marginal cost with marginal revenue (profit maximization). This output is then divided between the two markets, at the equilibrium marginal revenue level. Therefore, the optimum outputs are Qa and Qb. From the demand curve in each market we can determine the profit maximizing prices of Pa and Pb.

It is also important to note that the marginal revenue in both markets at the optimal output levels must be equal, otherwise the firm could profit from transferring output over to whichever market is offering higher marginal revenue.

Given that Market 1 has a price elasticity of demand of E1 and Market of E2, the optimal pricing ration in Market 1 versus Market 2 is .

Examples of price discrimination

Retail price discrimination

Manufacturers may sell their products to similarly situated retailers at different prices based solely on the volume of products purchased.

Travel industry

Airlines and other travel companies use differentiated pricing regularly, as they sell travel products and services simultaneously to different market segments. This is often done by assigning capacity to various booking classes, which sell for different prices and which may be linked to fare restrictions. The restrictions or "fences" help ensure that market segments buy in the booking class range that has been established for them. For example, schedule-sensitive business passengers who are willing to pay $300 for a seat from city A to city B cannot purchase a $150 ticket because the $150 booking class contains a requirement for a Saturday-night stay, or a 15-day advance purchase, or another fare rule that discourages, minimizes, or effectively prevents a sale to business passengers.

Notice however that in this example "the seat" is not really always the same product. That is, the business person who purchases the $300 ticket may be willing to do so in return for a seat on a high-demand morning flight, for full refundability if the ticket is not used, and for the ability to upgrade to first class if space is available for a nominal fee. On the same flight are price-sensitive passengers who are not willing to pay $300, but who are willing to fly on a lower-demand flight ( one leaving an hour earlier), or via a connection city (not a non-stop flight), and who are willing to forgo refundability.

On the other hand, an airline may also apply differential pricing to "the same seat" over time, e.g. by discounting the price for an early or late booking (without changing any other fare condition). This could present an arbitrage opportunity in the absence of any restriction on reselling. However, passenger name changes are typically prevented or financially penalized by contract.

Since airlines often fly multi-leg flights, and since no-show rates vary by segment, competition for the seat has to take in the spatial dynamics of the product. Someone trying to fly A-B is competing with people trying to fly A-C through city B on the same aircraft. This is one reason airlines use yield management technology to determine how many seats to allot for A-B passengers, B-C passengers, and A-B-C passengers, at their varying fares and with varying demands and no-show rates.

With the rise of the Internet and the growth of low fare airlines, airfare pricing transparency has become far more pronounced. Passengers discovered it is quite easy to compare fares across different flights or different airlines. This helped put pressure on airlines to lower fares. Meanwhile, in the recession following the September 11, 2001, attacks on the U.S., business travelers and corporate buyers made it clear to airlines that they were not going to be buying air travel at rates high enough to subsidize lower fares for non-business travelers. This prediction has come true, as vast numbers of business travelers are buying airfares only in economy class for business travel.

There are sometimes group discounts on rail tickets and passes. This may be in view of the alternative of going by car together.

Coupons

The use of coupons in retail is an attempt to distinguish customers by their reserve price. The assumption is that people who go through the trouble of collecting coupons have greater price sensitivity than those who do not. Thus, making coupons available enables, for instance, breakfast cereal makers to charge higher prices to price-insensitive customers, while still making some profit of customers who are more price-sensitive.

Premium pricing

For certain products, premium products are priced at a level (compared to "regular" or "economy" products) that is well beyond their marginal cost of production. For example, a coffee chain may price regular coffee at $1, but "premium" coffee at $2.50 (where the respective costs of production may be $0.90 and $1.25). Economists such as Tim Harford in the Undercover Economist have argued that this is a form of price discrimination: by providing a choice between a regular and premium product, consumers are being asked to reveal their degree of price sensitivity (or willingness to pay) for comparable products. Similar techniques are used in pricing business class airline tickets and premium alcoholic drinks, for example.

This effect can lead to (seemingly) perverse incentives for the producer. If, for example, potential business class customers will pay a large price differential only if economy class seats are uncomfortable while economy class customers are more sensitive to price than comfort, airlines may have substantial incentives to purposely make economy seating uncomfortable. In the example of coffee, a restaurant may gain more economic profit by making poor quality regular coffee—more profit is gained from up-selling to premium customers than is lost from customers who refuse to purchase inexpensive but poor quality coffee. In such cases, the net social utility should also account for the "lost" utility to consumers of the regular product, although determining the magnitude of this foregone utility may not be feasible.

Segmentation by age group, student status, ethnicity and citizenship

Many movie theaters, amusement parks, tourist attractions, and other places have different admission prices per market segment: typical groupings are Youth/Child, Student, Adult, Senior Citizen, Local and Foreigner. Each of these groups typically have a much different demand curve. Children, people living on student wages, and people living on retirement generally have much less disposable income. Foreigners may be perceived as being more wealthy than locals and therefore being capable of paying more for goods and services - sometimes this can be more than 10 times as much. Market stall-holders and individual public transport providers may also insist on higher prices for their goods and services when dealing with foreigners (sometimes called the "White Man Tax").[17][18] Some goods - such as housing - may be offered at cheaper prices for certain ethnic groups.[19]

Discounts for members of certain occupations

Some businesses may offer reduced prices members of some occupations, such as school teachers (see below), police and military personnel. In addition to increased sales to the target group, businesses benefit from the resulting positive publicity, leading to increased sales to the general public.

Retail incentives

A variety of incentive techniques may be used to increase market share or revenues at the retail level. These include discount coupons, rebates, bulk and quantity pricing, seasonal discounts, and frequent buyer discounts.

Incentives for industrial buyers

Many methods exist to incentivize wholesale or industrial buyers. These may be quite targeted, as they are designed to generate specific activity, such as buying more frequently, buying more regularly, buying in bigger quantities, buying new products with established ones, and so on. Thus, there are bulk discounts, special pricing for long-term commitments, non-peak discounts, discounts on high-demand goods to incentivize buying lower-demand goods, rebates, and many others. This can help the relations between the firms involved.

Gender-based examples

Gender-based price discrimination is the practice of offering identical or similar services and products to men and women at different prices when the cost of producing the products and services is the same.[20] In the United States, gender-based price discrimination has been a source of debate.[21] In 1992, the New York City Department of Consumer Affairs (“DCA”) conducted an investigation of “price bias against women in the marketplace”.[22] The DCA’s investigation concluded that women paid more than men at used car dealers, dry cleaners, and hair salons.[23] The DCA’s research on gender pricing in New York City brought national attention to gender-based price discrimination and the financial impact it has on women.

In 1995, California Assembly’s Office of Research studied the issue of gender-based price discrimination of services and estimated that women effectively paid an annual “gender tax” of approximately $1,351.00 for the same services as men.[24] It was also estimated that women, over the course of their lives, spend thousands of dollars more than men to purchase similar products.[24] For example, prior to the enactment of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act[25] (“Affordable Care Act”), health insurance companies charged women higher premiums for individual health insurance policies than men. Under the Affordable Care Act, health insurance companies are now required to offer the same premium price to all applicants of the same age and geographical locale without regard to gender.[26] However, there is no federal law banning gender-based price discrimination in the sale of products.[27] Instead, several cities and states have passed legislation prohibiting gender-based price discrimination on products and services.

International price discrimination

Pharmaceutical companies may charge customers living in wealthier countries a much higher price than for identical drugs in poorer nations, as is the case with the sale of antiretroviral drugs in Africa. Since the purchasing power of African consumers is much lower, sales would be extremely limited without price discrimination. The ability of pharmaceutical companies to maintain price differences between countries is often either reinforced or hindered by national drugs laws and regulations, or the lack thereof.[28]

Even online sales for non material goods, which do not have to be shipped, may change according to the geographic location of the buyer.

Academic pricing

Companies will often offer discounted goods and software to students and faculty at school and university levels. These may be labeled as academic versions, but perform the same as the full price retail software. Academic versions of the most expensive software suites may be free or significantly cheaper than the retail price of standard versions. Some academic software may have differing licenses than retail versions, usually disallowing their use in activities for profit or expiring the license after a given number of months. This also has the characteristics of an "initial offer" - that is, the profits from an academic customer may come partly in the form of future non-academic sales due to vendor lock-in.

Sliding scale fees

Sliding scale fees are when different customers are charged different prices based on their income, which is used as a proxy for their willingness or ability to pay. For example, some nonprofit law firms charge on a sliding scale based on income and family size. Thus the clients paying a higher price at the top of the fee scale help subsidize the clients at the bottom of the scale. This differential pricing enables the nonprofit to serve a broader segment of the market than they could if they only set one price.[29]

Weddings

Goods and services for weddings are sometimes priced at a higher rate than identical goods for normal customers.[30][31][32]

Two necessary conditions for price discrimination

There are two conditions that must be met if a price discrimination scheme is to work. First the firm must be able to identify market segments by their price elasticity of demand and second the firms must be able to enforce the scheme.[33] For example, airlines routinely engage in price discrimination by charging high prices for customers with relatively inelastic demand - business travelers - and discount prices for tourist who have relatively elastic demand. The airlines enforce the scheme by enforcing a no resale policy on the tickets preventing a tourist from buying a ticket at a discounted price and selling it to a business traveler (arbitrage). Airlines must also prevent business travelers from directly buying discount tickets. Airlines accomplish this by imposing advance ticketing requirements or minimum stay requirements — conditions that would be difficult for average business traveler to meet.[34]

User-controlled price discrimination

While the conventional theory of price discrimination generally assumes that prices are set by the seller, there is a variant form in which prices are set by the buyer, such as in the form of pay what you want pricing. Such user-controlled price discrimination exploits similar ability to adapt to varying demand curves or individual price sensitivities, and may avoid the negative perceptions of price discrimination as imposed by a seller.

See also

- Geo (marketing)

- Marketing

- Microeconomics

- Outline of industrial organization

- Pay what you want

- Ramsey problem

- Resale price maintenance

- Robinson-Patman Act

- Sliding scale fees

- Ticket resale

- Yield management

Notes

- ↑ Krugman, Paul R.; Maurice Obstfeld (2003). "Chapter 6: Economies of Scale, Imperfect Competition and International Trade". International Economics - Theory and Policy (6th ed.). p. 142.

- 1 2 3 4 Robert Phillips (2005). Pricing and Revenue Optimization. Stanford University Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-8047-4698-4.

- 1 2 3 4 Peter Belobaba; Amedeo Odoni; Cynthia Barnhart (2009). The Global Airline Industry. John Wiley & Sons. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-470-74472-7.

- ↑ William M. Pride; O. C. Ferrell (2011). Foundations of Marketing, 5th ed. Cengage Learning. p. 374. ISBN 1-111-58016-2.

- ↑ Ruth Macklin (2004). Double Standards in Medical Research in Developing Countries. Cambridge University Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-521-54170-1.

- ↑ Bernard M. Hoekman; Aaditya Mattoo; Philip English (2002). Development, Trade, and the WTO: A Handbook. World Bank Publications. p. 378. ISBN 978-0-8213-4997-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Carl Shapiro (1999). Information Rules: A Strategic Guide to the Network Economy. Harvard Business School Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-87584-863-1.

- 1 2 3 Paul Belleflamme; Martin Peitz (2010). Industrial Organization: Markets and Strategies. Cambridge University Press. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-521-86299-8.

- 1 2 David K. Hayes; Allisha Miller (2011). Revenue Management for the Hospitality Industry. John Wiley and Sons. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-118-13692-8.

- ↑ Robert Phillips (2005). Pricing and Revenue Optimization. Stanford University Press. pp. 82–83. ISBN 978-0-8047-4698-4.

- ↑ Lynne Pepall; Dan Richards; George Norman (2011). Contemporary Industrial Organization: A Quantitative Approach. John Wiley and Sons. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-118-13898-4.

- 1 2 Robert Phillips (2005). Pricing and Revenue Optimization. Stanford University Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-8047-4698-4.

- ↑ Robert Phillips (2005). Pricing and Revenue Optimization. Stanford University Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-8047-4698-4.

- ↑ ("Price Discrimination and Imperfect Competition", Lars A. Stole)

- ↑ Frank, Robert H. (2010): Microeconomics and Behavior, 8th Ed., McGraw-Hill Irwin, pp. 393-394.

- ↑ Frank, Robert H. (2010): Microeconomics and Behavior, 8th Ed., McGraw-Hill Irwin, p. 395.

- ↑ https://karenbryson.wordpress.com/2015/02/19/the-white-mans-tax/

- ↑ http://www.thebeijinger.com/blog/2014/06/18/beijings-white-man-tax-pegged-median-16-unscientific-survey

- ↑ http://www.malaysia-today.net/bumiputera-discount-a-sensitive-topic-that-must-be-addressed/

- ↑ See generally PRICE DISCRIMINATION, Black’s Law Dictionary (10th ed. 2014).

- ↑ See, e.g., Civil Rights--Gender Discrimination--California Prohibits Gender-Based Pricing--Cal. Civ. Code. § 51.6 (West Supp. 1996), 109 HARV. L. REV. 1839, 1839 (1996) (“Differential pricing of services is one of America's last remaining vestiges of formal gender-based discrimination.”); Joyce McClements and Cheryl Thomas, Public Accommodations Statutes: Is Ladies' Night Out?, 37 MERCER L. REV. 1605, 1618 (1986); Heidi Paulson, Ladies' Night Discounts: Should We Bar Them or Promote Them?, 32 B.C. L. Rev. 487, 528 (1991) (arguing that ladies' night promotions encourage paternalistic attitudes toward women and encourage stereotypes of both men and women).

- ↑ New York City Department of Consumer Affairs, Gypped by Gender: A Study of Price Bias Against Women in the Marketplace (1992).

- ↑ New York City Department of Consumer Affairs, Gypped by Gender: A Study of Price Bias Against Women in the Marketplace (1992). The study found when women bought used cars, they were twice as likely to have been quoted a higher price than men. Based on a survey of 80 hair salons across the five New York boroughs, the study also found that, on average, women paid 25 percent more for the same haircuts as men. Similarly, on average, women paid 27 percent more for the identical service of laundering a basic white cotton shirt.

- 1 2 California State Senate, Gender Tax Repeal Act of 1995, AB 1100 (Aug. 31, 1995).

- ↑ Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Pub. L. No. 111-148, 124 Stat. 119 (2010) (to be codified in scattered titles and sections)[hereinafter Affordable Care Act].

- ↑ Affordable Care Act § 2701, 124 Stat. 119, 37-38

- ↑ Danielle Paquette, Why you should always buy the men’s version of almost anything, The Washington Post (December 22, 2015), https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2015/12/22/women-really-do-pay-more-for-razors-and-almost-everything-else/.

- ↑ Pogge, Thomas (2008). World poverty and human rights : cosmopolitan responsibilities and reforms (PDF) (2. ed.). Cambridge [u.a.]: Polity Press. ISBN 978-0745641447.

- ↑ Zuckerman, Michael (August 7, 2014). "The Utah Lawyers Who Are Making Legal Services Affordable". The Atlantic. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ↑ http://freakonomics.com/2011/10/03/getting-married-then-get-ready-for-price-discrimination/

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/2013/12/08/magazine/the-wedding-fix-is-in.html?_r=0

- ↑ https://www.choice.com.au/shopping/shopping-for-special-occasions/weddings/articles/wedding-costs

- ↑ Samuelson & Marks, Managerial Economics 4th ed. (Wiley 2003)

- ↑ Samuelson & Marks, Managerial Economics 4th ed. (Wiley 2003) Airlines typically attempt to maximize revenue rather than profits because airlines variable costs are small. Thus airlines use pricing strategies designed to fill seats rather than equate marginal revenue and marginal costs.

References

- The Strategy and Tactics of Pricing by Thomas Nagle and Reed Holden. ISBN 0-13-026248-X.

- 'The Undercover Economist' by Tim Harford ISBN 978-0-349-11985-4

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Price discrimination. |

- Price Discrimination and Imperfect Competition Lars Stole

- Pricing Information Hal Varian.

- Price Discrimination for Digital Goods Arun Sundararajan.

- Price Discrimination Discussion piece from The Filter

- Joelonsoftware's blog entry on Price Discrimination

- Taken to the Cleaners? Steven Landsburg's explanation of Dry Cleaner pricing.