Project Azorian

|

| |

| Date | 1974 |

|---|---|

| Location | Pacific Ocean |

| Participants | CIA, Soviet Navy, U.S. Navy |

| Outcome | Successful recovery of a portion of Soviet submarine K-129 |

Coordinates: 40°06′N 179°54′E / 40.1°N 179.9°E[1]

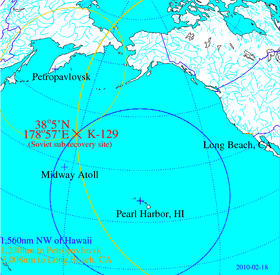

"Azorian" (erroneously called "Jennifer" by the press after its Top Secret Security Compartment)[2] was the code name for a U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) project to recover the sunken Soviet submarine K-129 from the Pacific Ocean floor in 1974, using the purpose-built ship Hughes Glomar Explorer.[3] The 1968 sinking of K-129 occurred approximately 1,560 nautical miles (2,890 km) northwest of Hawaii.[4] Project Azorian was one of the most complex, expensive, and secretive intelligence operations of the Cold War at a cost of about $800 million ($3.8 billion in 2016 dollars).

In addition to designing the recovery ship and its lifting cradle, the U.S. used concepts developed with Global Marine (see Project Mohole) that utilized their precision stability equipment to keep the ship nearly stationary above the target (and do this while lowering nearly three miles of pipe). They worked with scientists to develop methods for preserving paper that had been underwater for years in hopes of being able to recover and read the submarine's codebooks. The reasons this project was undertaken are likely to include the recovery of an intact nuclear missile (R-21, also known as NATO SS-N-5 Serb), and cryptological documents and equipment.

After the Soviet Union performed their unsuccessful search for K-129, the U.S. undertook a search, and by the use of acoustic data from four AFTAC sites and the Adak SOSUS array located the wreck of the submarine to within 5 nautical miles (9.3 km). The USS Halibut submarine used the Fish, a towed, 12-foot (3.7 m), 2-short-ton (1.8 t) collection of cameras, strobe lights, and sonar that was built to withstand extreme depths to detect seafloor objects. The recovery operation commenced covertly (in international waters) about six years later with the supposed commercial purpose of mining the sea floor for manganese nodules under the cover of Howard Hughes and Hughes Glomar Explorer.[5] While the ship did recover a portion of K-129, a mechanical failure in the grapple caused two-thirds of the recovered section to break off during recovery.

The Wreck of the K-129

In April 1968, Soviet Pacific Fleet surface and air assets were observed conducting a surge deployment to the North Pacific Ocean that involved some unusual search operations. The activity was evaluated by the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) as a possible reaction to the loss of a Soviet submarine. Soviet surface ship searches were centered on a location known to be associated with Soviet Golf II Class SSB strategic ballistic missile diesel submarine patrol routes. These submarines carried three nuclear missiles in an extended sail/conning tower and routinely deployed to within missile range of the U.S. west coast. The American SOSUS (Sea Spider) hydrophone network in the northern Pacific was tasked with reviewing its recordings in the hopes of detecting an implosion (or explosion) related to such a loss. Naval Facility (NAVFAC) Point Sur, south of Monterey, California, was able to isolate a sonic signature on its low frequency array (LOFAR) recordings of an implosion event that had occurred on March 8, 1968. Using NavFac Point Sur's date and time of the event, NavFac Adak and the U.S. West Coast NAVFAC were also able to isolate the acoustic event. With five SOSUS lines-of-bearing, Naval Intelligence was able to localize the site of the K-129 wreck to the vicinity of 40.1° N latitude and 179.9° E longitude (close to the International Date Line).[6]

After weeks of search, the Soviets were unable to locate their sunken boat, and Soviet Pacific Fleet operations gradually returned to a normal level. In July 1968, the U.S. Navy initiated "Operation Sand Dollar" with the deployment of USS Halibut from Pearl Harbor to the wreck site. Sand Dollar's objective was to find and photograph K-129. In 1965, Halibut had been configured to use deep submergence search equipment, the only such specially-equipped submarine then in U.S. inventory. The search locus provided by SOCUS was 1,200 square miles (3,100 km2), and the wreck was more than 3 miles (4.8 km) deep. Halibut located the wreck after three weeks of visual search using robotic remote-controlled cameras. (It took almost 5 months of search to find the wreck of the U.S. nuclear-powered submarine Scorpion in the Atlantic, also in 1968). Halibut is reported to have spent the next several weeks taking over 20,000 closeup photos of every aspect of the K-129 wreck, a feat for which Halibut received a special classified Presidential Unit Citation signed by Lyndon B. Johnson in 1968.

In 1970, based upon this photography, Defense Secretary Melvin Laird and Henry Kissinger, then National Security Advisor, proposed a clandestine plan to recover the wreckage so that the U.S. could study Soviet nuclear missile technology, as well as possibly recover cryptographic materials. The proposal was accepted by President Richard Nixon and the CIA was tasked to attempt the recovery.

Building Glomar Explorer, and its cover story

Global Marine Development Inc., the research and development arm of Global Marine Inc., a pioneer in deepwater offshore drilling operations, was contracted to design, build and operate "Hughes Glomar Explorer" in order to secretly salvage the sunken Soviet submarine from the ocean floor. The ship was built at the Sun Shipbuilding yard near Philadelphia. Billionaire businessman Howard Hughes — whose companies were already contractors on numerous classified US military weapons, aircraft and satellite contracts — agreed to lend his name to the project in order to support the cover story that the ship was mining manganese nodules from the ocean floor, but Hughes and his companies had no actual involvement in the project. K-129 was photographed at a depth of over 16,000 feet (4,900 m), and thus the salvage operation would be well beyond the depth of any ship salvage operation ever before attempted. On November 1, 1972, work began on the 63,000-short-ton (57,000 t), 619-foot-long (189 m) Hughes Glomar Explorer (HGE).

Recovery

Hughes Glomar Explorer employed a large mechanical claw, which Lockheed officially titled the "Capture Vehicle" but affectionately called Clementine. The capture vehicle was designed to be lowered to the ocean floor, grasp around the targeted submarine section, and then lift that section into the ship's hold. One requirement of this technology was to keep the floating base stable and in position over a fixed point 16,000 feet (4,900 m) below the ocean surface.

The capture vehicle was lowered and raised on a pipe string similar to those used on oil drilling rigs. Section by section, 60-foot (18 m) steel pipes were strung together to lower the claw through a hole in the middle of the ship. This configuration was designed by Western Gear Corp. of Everett, Washington. Upon a successful capture by the claw, the lift reversed the process — 60-foot (18 m) sections drawn up and removed one at a time. The salvaged "Target Object" was thus to be drawn into a moon pool, the doors of which could then be closed to form a floor for the salvaged section. This allowed for the entire salvage process to take place underwater, away from the view of other ships, aircraft, or spy satellites.

Sailing 3,008 nautical miles (5,571 km) from Long Beach, California on June 20, 1974, Hughes Glomar Explorer arrived at the recovery site July 4 and conducted salvage operations for over a month. During this period, at least two Soviet Navy ships visited the Glomar Explorer's work site, the oceangoing tug "SB-10", and the Soviet Missile Range Instrumentation Ship "Chazma".[4] It was found out after 1991 that the Soviets were tipped off about the operation and were aware that the CIA was planning some kind of salvage operation, but the military command believed it impossible that they could perform such a task and disregarded further intelligence warnings. Later on, Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin started sending urgent messages back to the Soviet Navy warning that an operation was imminent, Soviet military engineering experts reevaluated their positions and claimed that it was indeed possible (though highly unlikely) to recover the K-129, and ships in the area were ordered to report any unusual activity, although the lack of knowledge as to where the K-129 was located impeded their ability to stop any salvage operation.[6]

U.S. Major General Roland Lajoie stated that, according to a briefing he received by the CIA, during recovery operations, Clementine suffered a catastrophic failure, causing two-thirds of the already raised portion of K-129 to sink back to the ocean floor. Former Lockheed and Hughes Global Marine employees who worked on the operation have stated that several of the "claws" intended to grab the submarine fractured, possibly because they were manufactured from maraging steel, which is very strong, but not very ductile compared with other kinds of steel.

The recovered section included two nuclear torpedoes, and thus Project Azorian was not a complete failure. The bodies of six crewmen were also recovered, and were given a memorial service and with military honors, buried at sea in a metal casket because of radioactivity concerns. Other crew members have reported that code books and other materials of apparent interest to CIA employees aboard the vessel were recovered, and images of inventory printouts exhibited in the documentary[6] suggest that various submarine components, such as hatch covers, instruments and sonar equipment were also recovered. White's documentary also states that the ship's bell from K-129 was recovered, and was subsequently returned to the Soviet Union as part of a diplomatic effort. The CIA considered that the project was one of the greatest intelligence coups of the Cold War.[7]

The entire salvage operation was recorded by a CIA documentary film crew, but this film remains classified. A short portion of the film, showing the recovery and subsequent burial at sea of the six bodies recovered in the forward section of K-129, was given to the Russian Government in 1992.

Public disclosure

The New York Times suppresses its story

Jack Anderson has been credited as breaking the story of Hughes Glomar Explorer to a nationwide audience.[8] Rejecting a plea from the Director of Central Intelligence William Colby to suppress the story, Anderson said he released the story because "Navy experts have told us that the sunken sub contains no real secrets and that the project, therefore, is a waste of the taxpayers’ money."[8]

In February 1975, investigative reporter and former New York Times writer Seymour Hersh had planned to publish a story on Project Azorian. Bill Kovach, the New York Times Washington bureau chief at the time, said in 2005 that the government offered a convincing argument to delay publication — exposure at that time, while the project was ongoing, "would have caused an international incident." The New York Times published its account in March 1975,[9] after a story appeared in the Los Angeles Times, and included a five-paragraph explanation of the many twists and turns in the path to publication.[10] CIA director George H. W. Bush reported on several occasions to U.S. president Gerald Ford on media reports and the future use of the ship.[11][12] The CIA concluded that it seemed unclear what, if any, action was taken by the Soviet Union after learning of the story.[13]

Freedom of Information Act request and the Glomar response

After stories had been published about the CIA's attempts to stop publication of information about Project Azorian, Harriet Ann Phillippi, a journalist, filed a Freedom of Information Act request with the CIA for any records about the CIA's attempts. The CIA refused to either confirm or deny the existence of such documents.[14] This type of non-responsive reply has since come to be known as the "Glomar response" or "Glomarization."[15]

1998 release of video

A video showing the 1974 memorial services for the six Soviet seamen whose bodies were recovered by Project Azorian was forwarded by the U.S. to Russia in the early 1990s. Portions of this video were shown on television documentaries concerning Project Azorian, including a 1998 Discovery Channel special called A Matter of National Security (based on Clyde W. Burleson's book, The Jennifer Project (1977)) and again in 1999, on a PBS Cold War submarine episode of NOVA.[16][17]

2010 release of 1985 CIA article

In February 2010, the CIA released an article from the fall 1985 edition of the CIA internal journal Studies in Intelligence following an application by researcher Matthew Aid at the National Security Archive[18] to declassify the information under the US Freedom of Information Act. Exactly what the operation managed to salvage remained unclear.[19] The report was written by an unidentified participant in Project Azorian.

2010 release of President Ford cabinet meeting

During the aftermath of the publication of the "Project Jennifer" story by Seymour Hersh, U.S. President Gerald Ford, Secretary of Defense James R. Schlesinger, Philip Buchen (Counsel to the President), John O. Marsh, Jr. (Counselor to the President), Ambassador Donald Rumsfeld, Lt. General Brent Scowcroft (Deputy Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs), and William Colby (Director of Central Intelligence) discussed the leak and whether the Ford administration would react to Hersh's story. In a cabinet meeting on March 19, 1975 (the same day The New York Times published the story), Secretary of Defense Schlesinger is quoted as saying,

This episode has been a major American accomplishment. The operation is a marvel -- technically, and with maintaining secrecy.[20][21]

With the words "marvel" and "major American accomplishment" used to describe Operation Matador, it is obvious that the Secretary of Defense indicated at least some form of success that should be confirmed publicly.[22] The director of CIA, William Colby dissented, recalling the U-2 crisis, saying:

I think we should not put the Soviet Union under such pressure to respond.[20][21]

The result of the meeting was to stonewall, causing the Los Angeles Times to publish a 4-page story the next day by Jack Nelson with the headline, "Administration Won't Talk About Sub Raised by CIA."[22]

Conspiracy theory

Time magazine[23] as well as a court filing by Felice D. Cohen and Morton H. Halperin on behalf of the Military Audit Project[24] suggest that the alleged project goal of raising a Soviet submarine might itself have been a cover story for another secret mission. Tapping of undersea communication cables, the installation of an underwater equivalent of a missile silo, and installation and repair of surveillance systems to monitor ship and submarine movements are listed as possibilities for the actual purpose of such a secret mission.[25]

New eyewitness account

W. Craig Reed, in Red November: Inside the Secret U.S. - Soviet Submarine War (2010), contains an inside account of Project Azorian provided by Joe Houston, the senior engineer who designed leading-edge camera systems used by the Glomar Explorer team to photograph K-129 on the ocean floor. The team needed pictures that offered precise measurements to design the grappling arm and other systems used to bring the sunken submarine up from the bottom. Houston worked for the mysterious "Mr. P" (John Parangosky) who worked for CIA Deputy Director Carl E. Duckett — the two leaders of Project Azorian. Duckett later worked with Houston at another company, and intimated that the CIA may have recovered much more from the K-129 than admitted to publicly. Reed also details how the mini-sub technology used by the submarine Halibut to find K-129 was used for subsequent Operation Ivy Bells missions to wiretap underwater Soviet communications cables.

In a documentary film titled Azorian: The Raising Of The K-129, which was produced by Michael White and released in 2009, three principals who participated in the design of the Hughes Glomar Explorer heavy lift system and the Lockheed capture vehicle (CV or claw) gave on-camera interviews. These individuals were also on board the ship during the mission and were intimately involved with the recovery operation. They are Sherman Wetmore, Global Marine heavy lift operations manager; Charlie Johnson, Global Marine heavy lift engineer; and Raymond Feldman, Lockheed Ocean Systems senior staff engineer. These three, plus others who were not on board during the recovery but were cleared on all aspects of the mission, confirmed that only 38 feet of the bow was eventually recovered. The intent was to recover the forward two thirds (138 feet) of K-129, which had broken off from the rear section of the submarine and was designated the Target Object (TO). The capture vehicle successfully lifted the TO from the ocean floor. On the way up, a failure of part of the capture vehicle caused the loss of 100 feet, including the sail, of the TO. In October 2010 a book based on the film, Project Azorian: The CIA And The Raising of the K-129 by Norman Polmar and Michael White, was published. The book contains additional documentary evidence about the effort to locate the submarine and the recovery operation.[6]

See also

- HMS Poseidon, a British submarine sunk in 1931 and secretly lifted by China in 1972

References

Notes

- ↑ PRC68.com

- ↑ Matthew Aid with William Burr and Thomas Blanton (2010-02-12). "Project Azorian: The CIA's Declassified History of the Glomar Explorer". The National Security Archive. Retrieved 2010-02-13.

- ↑ Wiegley, Roger D., LT (JAG) USN "The Recovered Sunken Warship: Raising a Legal Question" United States Naval Institute Proceedings January 1979 p.30

- 1 2 "Project Azorian: The Story of the Hughes Glomar Explorer" (PDF). Studies in Intelligence, CIA. Fall 1985. Retrieved 2010-02-13.

- ↑ Polmar, Norman; White, Michael (2010). Project Azorian : the CIA and the raising of the K-129 (null ed.). Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-690-2.

- 1 2 3 4 Michael White (February 8, 2011). Azorian: The Raising of the K-129 (DVD). Michael White Films. ISBN 978-1-59114-690-2. ASIN B0047H7PYQ.

- ↑ "Project AZORIAN". CIA. November 21, 2012. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- 1 2 Robarge, David (March 2012). "The Glomar Explorer in Film and Print" (PDF). Studies in Intelligence. 56 (1): 28–29. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- ↑ Phelan, James. "An Easy Burglary Led to the Disclosure of Hughes-C.I.A. Plan to Salvage Soviet Sub"(fee). The New York Times 27 March 1975, p. 18.

- ↑ Prying open the Times - Salon.com

- ↑ Bush, George H.W. (2 Dec 1976). "Meeting with the President, Oval Office, 1. December 1976, 9:00 to 9:30 a.m." (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency.

- ↑ Bush, George H.W. (12 July 1976). "Meeting with the President, Oval Office, 12. July 1976, 8:00 a.m." (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency.

- ↑ "Implications for US-Soviet Relations of Certain Soviet Activities: Microwaves in Moscow (section 13)" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency. June 1976.

- ↑ Philippi v. CIA (Turner et al.), U.S. Court of Appeals, 211 U.S. App. D.D. 95, June 25, 1981

- ↑ FOIA Update, Vol. VII, No. 1, Page 3 (1986). "OIP Guidance: Privacy "Glomarization"". United States Department of Justice.

- ↑ Clyde W, Burleson, author, "The Jennifer Project", 1977

- ↑ PBS,Nova, "Submarines, Secrets and Spies". Broadcast January, 1999.

- ↑ "Gone fishing: Secret hunt for a sunken Soviet sub". Associated Press. February 13, 2010.

- ↑ "US admits salvaging sunken Soviet submarine - The American government has finally revealed details of a secret mission to raise a sunken Soviet submarine|

- 1 2 Matador Meeting

- 1 2 http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/nukevault/ebb305/doc03.pdf

- 1 2 Document Friday: The Origins of "Glomar" Declassified, William Burr, June 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Espionage: The Great Submarine Snatch". Time Magazine. 1975-03-31.

- ↑ http://www.leagle.com/decision/19811380656F2d724_11252

- ↑ "656 F.2d 724; 211 U.S.App.D.C. 135, 7 Media L. Rep. 1708: MILITARY AUDIT PROJECT, Felice D. Cohen, Morton H. Halperin, Appellants, v. William CASEY, Director of Central Intelligence, et al.; No. 80-1110.". United States Court of Appeals, District of Columbia Circuit. 1981.

Bibliography

- Craven, John (2001). "The Hunt for Red September: A Tale of Two Submarines". The Silent War: The Cold War Battle Beneath the Sea. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 198–222. ISBN 0-684-87213-7.

- Dunham, Roger C. (1996) Spy Sub - Top Secret Mission To The Bottom Of The Pacific New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-451-40797-0

- Reed, W. Craig (2010) Red November: Inside the Secret U.S. - Soviet Submarine War New York: William Morrow. ISBN 978-0-06-180676-6

- Polmar, Norman and White, Michael (2010) Project AZORIAN: The CIA And The Raising of the K-129, Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-690-2

- Presidential Unit Citation - USS Halibut - 1968

- Sharp, David (2012). The CIA's Greatest Covert Operation: Inside the Daring Mission to Recover a Nuclear-Armed Soviet Sub. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. p. 344. ISBN 978-0-7006-1834-7.

- Sontag, Sherry (1998). Blind Man's Bluff: The Untold Story of American Submarine Espionage. New York: Harper. ISBN 0-06-103004-X.

- Varner, Roy and Collier, Wayne. (1978) A Matter of Risk: The Incredible Inside Story of the CIA's Hughes Glomar Explorer Mission to Raise a Russian Submarine

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Project Azorian. |

- AZORIAN The Raising of the K-129 / 2009 - 2 Part TV Documentary / Michael White Films Vienna

- Project Jennifer and the Hughes Glomar Explorer

- Extensive bibliography

- Personal account by a Lockheed Engineer of the K-129 salvage effort while aboard Glomar Explorer Amazon review by Ray Feldman

- Red November, Inside the Secret U.S. Soviet Submarine War

.jpg)