Proto-Dravidian language

| Proto-Dravidian | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proto-South-Dravidian | Proto-South-Central Dravidian | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proto-Tamil-Kannada | Proto-Telugu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proto-Tamil-Toda | Proto-Kannada | Proto-Telugu | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proto-Tamil-Kodagu | Kannada | Telugu | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proto-Tamil-Malayalam | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proto-Tamil | Malayalam | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tamil | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Dravidian culture and history |

|---|

|

|

History |

|

Regions

|

|

People |

| Portal:Dravidian civilizations |

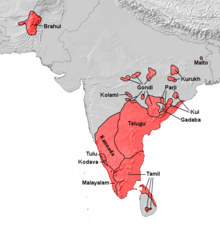

Proto-Dravidian is the linguistic reconstruction of the common ancestor of the Dravidian languages.[1] It is thought to have differentiated into Proto-North Dravidian, Proto-Central Dravidian, and Proto-South Dravidian, although the date of diversification is still debated.[2]

History

As a proto-language, the Proto-Dravidian language is not itself attested in the historical record. Its modern conception is based solely on reconstruction. It is suggested that the language was spoken in the 4th millennium BCE, and started disintegrating into various branches around 3rd millennium BCE.[3]

Reconstructed language

Vowels: Proto-Dravidian contrasted between five short and long vowels: *a, *ā, *i, *ī, *u, *ū, *e, *ē, *o, *ō. The sequences *ai and *au are treated as *ay and *av (or *aw)[4]

Consonants: Proto-Dravidian is reconstructible with the following consonant phonemes (Subrahmanyam 1983:p40, Zvelebil 1990, Krishnamurthi 2003):

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | *m | *n | *ṉ | *ṇ | *ñ | (*ṅ) | |

| Plosive | *p | *t | *ṯ | *ṭ | *c | *k | |

| Fricative | *ḻ (*ṛ, *r̤) | (*h) | |||||

| Flap | *r | ||||||

| Approximant | *v | *l | *ḷ | *y |

The alveolar stop *ṯ in many daughter languages developed into an alveolar trill /r/. The stop sound is retained in Kota and Toda (Subrahmanyam 1983). Malayalam still retains the original (alveolar) stop sound in gemination. (ibid). In Old Tamil it took the enunciative vowel like the other stops. In other words, *ṯ (or *ṟ) did not occur word-finally without the enunciative vowel (ibid).

Velar nasal *ṅ occurred only before *k in Proto-Dravidian (as in many of its daughter languages). Therefore, it is not considered a separate phoneme in Proto-Dravidian. However, it attained phonemic status in languages like Malayalam, Gondi, Konda and Pengo due to the simplification of the original sequence *ṅk to *ṅ. (Subrahmanyam 1983)

The glottal fricative *h has been proposed by Bh. Krishnamurthi to account for the Old Tamil Aytam (Āytam) and other Dravidian comparative phonological phenomena (Krishnamurthi 2003).

The Northern Dravidian languages Kurukh, Malto and Brahui are not easily derivable from the traditional Proto-Dravidian phonological system. McAlpin (2003)[5] proposes that they have branched off from an earlier stage of Proto-Dravidian than the conventional reconstruction, which would only apply to the other languages. He suggests reconstructing a richer system of dorsal stop consonants:

| Early Proto-Dravidian | Late Proto-Dravidian (Proto-Non-North Dravidian) | Proto-Kurukh-Malto | Brahui |

|---|---|---|---|

| *c | *c | *c | |

| *kʲ | *c | *k | k |

| *k | *k | *k | k |

| *q | *k | *q | x k / _i(ː) |

Speakers

The origin and territory of the Proto-Dravidian speakers is uncertain, but some suggestions have been made based on the reconstructed Proto-Dravidian vocabulary. The reconstruction has been done on the basis of cognate words present in the different branches (Northern, Central and Southern) of the Dravidian language family.[6]

According to Dorian Fuller (2007), the botanical vocabulary of Proto-Dravidian is characteristic of the dry deciduous forests of central and peninsular India. This region extends from Saurashtra and Central India to South India. It thus represents the general area in which the Dravidians were living before separation of branches.[6]

According to Franklin Southworth (2005), the Proto-Dravidian vocabulary is characteristic of a rural economy based on agriculture, animal husbandry and hunting. However, there are some indications of a society more complex than a rural one:[7]

- Words for an upper storey and beam

- Metallurgy

- Trade

- Payment of dues (possibly taxes or contributions to religious ceremonies)

- Social stratification

These evidences are not sufficient to determine with certainty the territory of the Proto-Dravidians. These characteristics can be accommodated within multiple contemporary cultures, including:[7]

- 2nd and 3rd millennium BCE Neolithic-Chalcolithic cultures of present-day western Rajasthan, Deccan and other parts of the peninsula.

- Indus Valley civilization sites in Saurashtra (Sorath) area of present-day Gujarat

Asko Parpola identifies Proto-Dravidians with the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC) and the Meluhha people mentioned in Sumerian records. According to him, the word "Meluhha" derives from the Dravidian words mel-akam ("highland country"). It is possible that the IVC people exported sesame oil to Mesopotamia, where it was known as ilu in Sumerian and ellu in Akkadian. One theory is that these words derive from the Dravidian name for sesame (el or ellu). However, Michael Witzel, who associates IVC with the ancestors of Munda speakers, suggests an alternative etymology from the para-Munda word for wild sesame: jar-tila. Munda is an Austroasiatic language, and the substratum (including loanwords) in Dravidian languages shows that the Austroasiatic people arrived in India before the Dravidians.[8]

Notes

- ↑ Andronov 2003, p. 299.

- ↑ Bhadriraju Krishnamurti (16 January 2003). The Dravidian Languages. Cambridge University Press. p. 492. ISBN 978-1-139-43533-8.

- ↑ [ https://books.google.com/books?id=chvjAAAAMAAJ&q=the+proto-+Dravidian+linguistic+community+disintegrated+at+the+beginning+of+the+4th+millennium+B.+C&dq=the+proto-+Dravidian+linguistic+community+disintegrated+at+the+beginning+of+the+4th+millennium+B.+C&hl=en&sa=X&redir_esc=y History and Archaeology, Volume 1, Issues 1-2] p.234, Department of Ancient History, Culture, and Archaeology, University of Allahabad

- ↑ Baldi, Philip (1990). Linguistic Change and Reconstruction Methodology. Walter de Gruyter. p. 342. ISBN 3-11-011908-0.

- ↑ McAlpin, David W. (2003). "Velars, Uvulars and the Northern Dravidian hypothesis". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 123:3: 521–546.

- 1 2 McIntosh 2008, p. 353.

- 1 2 McIntosh 2008, p. 353-354.

- ↑ McIntosh 2008, p. 354.

References

- Krishnamurti, B., The Dravidian Languages, Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-521-77111-0

- Subrahmanyam, P.S., Dravidian Comparative Phonology, Annamalai University, 1983.

- Zvelebil, Kamil., Dravidian Linguistics: An Introduction", PILC (Pondicherry Institute of Linguistics and Culture), 1990

- McIntosh, Jane R. (2008). The Ancient Indus Valley : New Perspectives. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576079072.

- Andronov, Mikhail Sergeevich (2003). A Comparative Grammar of the Dravidian Languages. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-04455-4.

See also

External links

T. Burrow (1984). Dravidian Etymological Dictionary, 2nd Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-864326-5. Retrieved 2008-10-26.