Tamil nationalism

Tamil nationalism asserts that Tamils are a nation and promotes the cultural unity of Tamil people. It expresses itself in the form of linguistic purism ("Pure Tamil"), nationalism and irredentism ("Tamil Eelam"), Social equality ("Self-Respect Movement") and Tamil Renaissance.

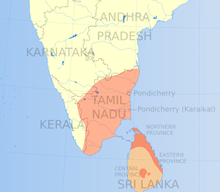

Tamils are one of the oldest civilisations in the world with a rich culture and language.[1] Originally, Tamil people ruled in Tamilakam and parts of Sri Lanka. During the colonial period, the Tamil areas came under the rule of British India and Ceylon. This situation completely eradicated the sovereignty of Tamils and reduced them to a minority status under political model implemented by British on their process of granting independence to their colonies. Since independence, Tamil separatist movements have been suppressed in Sri Lanka and India.[2]

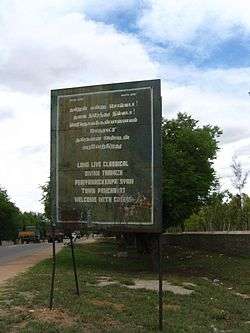

A famous quote by Tamil poet Kannadasan about the Tamils as a stateless nation.[3]

| “ | There is no state without Tamils, there is no state for the Tamils. | ” |

Sri Lanka

Since the Anti Tamil pogroms of 1983, known as Black July, Tamil nationalists in Sri Lanka attempted to create an independent state (Tamil Eelam) amid the increasing political and physical violence against ordinary Tamils by the Sri Lankan government which was dominated by Sinhalese Buddhist nationalism. After the island's independence from Britain, the Sri Lankan government passed the Citizenship Act of 1948, which made more than a million Tamils of Indian origin stateless. The government also passed a Sinhala Only Act, which severely threatens the natural presence of minority language as well as damaging their social mobility..

In addition, the government also initiated Sinhalese colonisation scheme which is targeted to dilute the numerical presence of the minorities as well as to occupy the traditional economics such as agriculture and fisheries which is held by Tamils since immemorial times. In response an armed group known as the LTTE or Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam emerged to safeguard the interest and rights of Tamils in their own land. Their violence and assassinations led them to be declared as terrorist by Malaysia, European Union and the USA. The resulting civil war has taken the lives of more than 70,000 Sri Lankan Tamils since 1983 alone.[4]

India

The Indian Tamil Nationalism is the smaller section of the Dravidian Nationalism which consisted of all the four major Dravidian language in the South India. The Dravidian Nationalism was popularised by a series of small movements and organisations that contended that the South Indians, and a cultural entity that was different from the Indo-Aryans of North India. A new morphed ideology of the Dravidian nationalism gained momentum within the Tamil speakers during the 1930 and 1950. The Dravidian nationalism failed outside Tamil Nadu to find supporters. By the late 1960, the political parties who were espousing Dravidian ideologies gained power within the state of Tamil Nadu.[5][6] Subsequently the Nationalist ideologies lead to the argument by Tamil leaders that, at minimal, that Tamils must have self-determination or, at maximum, secession from India[7]

Since the 1969 election victory of Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) under C N Annadurai, Tamil nationalism has been a permanent feature of the government of Tamil Nadu. The DMK came to power on the plank of opposing Hindi monopoly/imposition. Prior to coming to power, they also openly declared to fight for Tamil independence from India. But since the Indian government had added a new legislation that outlawed anyone wanting independence from India, under the sedition act, and that made political parties to lose their right to stand in election, the DMK dropped this demand. With this, the drive for secession became weaker with most mainstream political parties, except a few, who instead committed to development of Tamil Nadu within a united India. Most major Tamil Nadu regional parties such as DMK, All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK), Viduthalai Chiruthaigal Katchi (VCK), Pattali Makkal Katchi (PMK) and Marumalarchi Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (MDMK) frequently participate as coalition partners of other pan-Indian parties in the Union Government of India at New Delhi.

In 1958, S. P. Adithanar founded the "We Tamils" party who wanted the creation of a homogeneous Tamil state incorporating Tamil speaking areas of India and Sri Lanka. In 1960, the party organized a statewide protest who demanded the establishment of sovereign Tamil Nadu. During the protest were maps of Republic of India (with Tamil Nadu left out) burnt. We Tamils party lost the elections in 1962 and was merged 1967 with the DMK.[8][9] The outbreak of the Sri Lankan civil war lead that the Tamil nationalism in India took a new shape. In India emerged small Tamil militant groups such as Tamil Nadu Liberation Army led by Thamizharasan, who aspired an independent Tamil Nadu. After his death, the group is believed to have splintered into factions. TNLA was banned by the Government of India.[10] Another banned Tamil secessionist group in India was the Tamil National Retrieval Troops (TNRT) founded by P. Ravichandran in the late-1980s. TNRT fought for an independent Tamil homeland and followed the goal to unite Tamil Nadu and Tamil Eelam to a greater Tamil state.[11]

In October 2008, amid build up in shelling into the Tamil civilian areas by the Sri Lankan military, with the army moving in on the LTTE and the navy battling the latter's sea patrol, Indian Tamil MP's, including those supporting the Singh government in the DMK and PMK, threatened to resign en masse if the Indian government did not pressure the Lankan government to cease firing on civilians. In response, the Indian government reported it had upped the ante on the Lankan government to ease tensions.[12] Ever since, the DMK, apart from the 2G corruption scandals, has seen a steady decline in popularity in Tamil Nadu. Many Tamils felt disenfranchised with the DMK, that it did not act to do much to stop the genocide of Tamils in Sri Lanka.[13]

K. Muthukumar a Tamil journalist and activist in Tamil Nadu committed suicide, because the government failed to save Sri Lankan Tamils. His death instantly triggered widespread strikes, demonstrations and public unrest in Tamil Nadu.[14] There is also deep resentment against India among some Tamils, that it aided the Sri Lankan state in the 2009 genocide.[15][16][17] This led to minor incidents like Tamil nationalists turning out in support of the Eelam rebels when Chennai-based The Hindu was alleged to have been supporting the Government of Sri Lanka. Editor-in-Chief of The Hindu, N Ram named members of the Periyar Dravidar Kazhagam, Thamizh Thesiya Periyakkam,[18] some lawyers, and law college students as responsible for incidents of vandalism at their offices.

The Tamil nationalist party Naam Tamilar Katchi arose 18 May 2010 as a result of the bloody end of the Sri Lankan civil war. Main agenda of this party is the liberation of Tamil Eelam, only Tamils should rule in Tamil Nadu and to spread the importance of Tamil language and unity of Tamils, irrespective of religion and caste.[19]

2013 it came to series of Anti-Sri Lanka protests initiated by the Students Federation for Freedom of Tamil Eelam. The students demanded justice for Sri Lankan Tamils and a UN referendum on the formation of Tamil Eelam.[20] Tamil organizations, parties and the Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu demand an International Investigation of Sri Lankan war crimes and a UN referendum among Sri Lankan Tamils on the formation of Tamil Eelam.[21][22][23]

Linguistic purism

History

The anti-Hindi agitation was a form of resistance to the imposition of the Hindi language throughout India. C Rajagopalachari (Rajaji), who wanted to reinstate the “Varna system” in India, tried to impose Hindi as the national language, with Hindi taught in all Indian schools. This move was opposed by Periyar, who started an agitation that lasted for about three years. The agitation involved fasts, conferences, marches, picketing and protests. The government responded with a crackdown resulting in the death of two protesters and the arrest of 1,198 persons including women and children. The Congress Government of the Madras State, called in paramilitary forces to quell the agitation; their involvement resulted in the deaths of about seventy persons (by official estimates) including two policemen. Several Tamil leaders supported the continuation of the usage of English as the official language of India. To calm the situation, Indian Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri gave assurances that English would continue to be used as the official language as long the non-Hindi speaking states wanted. The riots subsided after Shastri's assurance, as did the student agitation.

Four states - Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan[24]- have been granted the right to conduct proceedings in their High Courts in their official language, which, for all of them, was Hindi. However, the only non-Hindi state to seek a similar power - Tamil Nadu, which sought the right to conduct proceedings in Tamil in its High Court - had its application rejected by the central government earlier, which said it was advised to do so by the Supreme Court.[25] In 2006, the law ministry said that it would not object to Tamil Nadu state's desire to conduct Madras High Court proceedings in Tamil.[26][27][28][29][30] In 2010, the Chief Justice of the Madras High Court allowed lawyers to argue cases in Tamil...[31]

Basis in pre-modern literature

Although nationalism itself is a modern phenomenon, the expression of linguistic identity found in the modern Pure Tamil movement has pre-modern antecedents, in a "loyalty to Tamil" (as opposed to Sanskrit) visible in ancient Sangam literature.[32] The poems of Sangam literature imply a consciousness of independence or separateness from neighbouring regions.[33] Similarly, Silappadhikaaram, a post-Sangam epic, posits a cultural integrity for the entire Tamil region[34] and has been interpreted by Parthasarathy as presenting "an expansive vision of the Tamil imperium" which "speaks for all Tamils."[35] Subrahmanian sees in the epic the first expression of Tamil nationalism,[34] while Parthasarathy says that the epic shows "the beginnings of Tamil separatism."[36]

Medieval Tamil texts also demonstrate features of modern Tamil linguistic purism, most notably the claim of parity of status with Sanskrit which was traditionally seen in the rest of the Indian subcontinent as being a prestigious, trans-local language. Texts on prosody and poetics such as the 10th century Yaapparungalakkaarihai and the 11th century Veerasoazhiyam, for example, treat Tamil as the equal of Sanskrit in terms of literary prestige, and use the rhetorical device of describing Tamil as a beautiful young lady and as a pure, divine language[37] both of which are also central in modern Tamil nationalism.[38] Vaishnavite[39] and Shaivite[40] commentators took the claim of divinity one step further, claiming for Tamil a liturgical status, and seeking to endow Tamil texts with the status of a "fifth Veda."[41] Vaishnavite commentators such as Nanjiyar went one step further, declaring that people who were not Tamil lamented the fact that they were not born in a place where such a wonderful language was spoken.[42] This trend was not universal, and there were also authors who sought to argue and work against Tamil distinctiveness through, amongst other things, Sanskritisation.[43]

See also

- Dravidian Nationalism

- Dravida Nadu

- Sri Lankan Tamil nationalism

- Tamil Eelam

- LTTE

- Politics of Tamil Nadu

Notes

- ↑ In Search Of The First Civilizations (2013), p. 78.

- ↑ India, Sri Lanka and the Tamil crisis, 1976-1994: an international perspective (1995), Alan J. Bullion, p.32.

- ↑ Historical Dictionary of the Tamils (2007), p. 319.

- ↑ "FBI — Taming the Tamil Tigers". FBI.

- ↑ Caste, Nationalism and Ethnicity: An Interpretation of Tamil Cultural History and Social Order, p. 57-71.

- ↑ Moorti, S. (2004). "Fashioning a Cosmopolitan Tamil Identity: Game Shows, Commodities and Cultural Identity". Media, Culture & Society. 26 (4): 549. doi:10.1177/0163443704044217.

- ↑ Kohli, A. (2004). "Federalism and the Accommodation of Ethnic Nationalism". Federalism and Territorial Cleavages: 285–288. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

- ↑ "We Tamils party S. P. Adithanar". WordPress.

- ↑ Dynamics of Tamil Nadu Politics in Sri Lankan Ethnicity, capter IV

- ↑ "Tamil Nadu Liberation Army (TNLA)". ww.satp.org.

- ↑ "Tamil National Retrieval Troops (TNRT)". ww.satp.org.

- ↑ "India asks Lanka to protect civilians". The Times Of India. 18 October 2008.

- ↑ "Why Tamil Nadu is right to call Sri Lanka's 'war' a genocide". Firstpost.com.

- ↑ "Indian journalist's self-immolation was an attempt to prevent Sri Lanka's Tamil Genocide". salem-news.com.

- ↑ "Indian forces took part in Lankan war: Plea". Times Of India.

- ↑ "Sri Lanka: A call for arms". India Today.

- ↑ "Russia and India to sell arms to Sri Lanka". Tamil Guardian.

- ↑ "tamizhdesiyam". tamizhdesiyam.blogspot.com.

- ↑ "Seeman calls for vote bank to protect Tamils". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ↑ "Students across Tamil Nadu join anti-Lanka stir". indiatimes.com.

- ↑ "Jayalalithaa calls for a referendum on separate Eelam". indiatimes.com.

- ↑ "T.N. Assembly demands referendum on Eelam". thehindu.com.

- ↑ "Tamil Nadu Assembly Calls for Probe Into Sri Lanka's Alleged War Crimes". ndtv.com.

- ↑ "Bar & Bench". Bar & Bench.

- ↑ Special Correspondent (12 March 2007), "Karunanidhi stands firm on Tamil in High Court", The Hindu, Chennai, India, p. 1.

- ↑ "No objection to Tamil as court language: A.P. Shah". The Hindu.

- ↑ Silobreaker: Make Tamil the language of Madras High Court: Karu

- ↑ "Karunanidhi hopeful of Centre's announcement". The Hindu.

- ↑ indianexpress.com

- ↑ "Government of Tamil Nadu : Archives of Press Releases - Tamil Nadu Government Portal" (PDF). tn.gov.in.

- ↑ "Advocate argues in Tamil in High Court". The New Indian Express. 23 June 2010. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ↑ Steever 1987, p. 355

- ↑ Abraham 2003, pp. 211, 217

- 1 2 Subrahmanian 1981, pp. 23–24

- ↑ Parthasarathy 1993, pp. 1–2

- ↑ Parthasarathy 1993, p. 344

- ↑ Monius 2000, pp. 12–13

- ↑ Ramaswamy 1993, pp. 690–698

- ↑ Narayanan 1994, p. 26

- ↑ Peterson 1982, p. 77

- ↑ Cutler 1991, p. 770.

- ↑ Clooney 1992, pp. 205–206

- ↑ Pandian 1994, p. 87; Kailasapathy 1979, p. 32

References

- Abraham, Shinu (2003), "Chera, Chola, Pandya: Using archaeological evidence to identify the Tamil kingdoms of early historic South India", Asian Perspectives, 42 (2): 207–223, doi:10.1353/asi.2003.0031

- Clooney, Francis X. (1992), "Extending the Canon: Some Implications of a Hindu Argument about Scripture", The Harvard Theological Review, 85 (2): 197–215

- Cutler, Norman; Peterson, Indira Viswanathan; Piḷḷāṉ; Carman, John; Narayanan, Vasudha; Pillan (1991), "Tamil Bhakti in Translation", Journal of the American Oriental Society, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 111, No. 4, 111 (4): 768–775, doi:10.2307/603406, JSTOR 603406

- Kailasapathy, K. (1979), "The Tamil Purist Movement: A re-evaluation", Social Scientist, Social Scientist, Vol. 7, No. 10, 7 (10): 23–51, doi:10.2307/3516775, JSTOR 3516775

- Kohli, A. (2004), "Federalism and the Accommodation of Ethnic Nationalism", in Amoretti, Ugo M.; Bermeo, Nancy, Federalism and Territorial Cleavages, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 281–299, ISBN 0-8018-7408-4, retrieved 2008-04-25

- Moorti, S. (2004), "Fashioning a Cosmopolitan Tamil Identity: Game Shows, Commodities and Cultural Identity", Media, Culture & Society, 26 (4): 549–567, doi:10.1177/0163443704044217

- Narayanan, Vasudha (1994), The Vernacular Veda: Revelation, Recitation, and Ritual, Studies in Comparative Religion, University of South Carolina Press, ISBN 0-87249-965-0

- Palanithurai, G. (1989), Changing Contours of Ethnic Movement: A Case Study of the Dravidian Movement, Annamalai University Dept. of Political Science Monograph series, No. 2, Annamalainagar: Annamalai University

- Pandian, M.S.S. (1994), "Notes on the transformation of 'Dravidian' ideology: Tamilnadu, c. 1900-1940", Social Scientist, Social Scientist, Vol. 22, No. 5/6, 22 (5/6): 84–104, doi:10.2307/3517904, JSTOR 3517904

- Parthasarathy, R. (1993), The Cilappatikaram of Ilanko Atikal: An Epic of South India, New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 0-231-07848-X

- Peterson, Indira V. (1982), "Singing of a Place: Pilgrimage as Metaphor and Motif in the Tēvāram Songs of the Tamil Śaivite Saints", Journal of the American Oriental Society, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 102, No. 1, 102 (1): 69–90, doi:10.2307/601112, JSTOR 601112.

- Steever, Sanford (1987), "Review of Hellmar-Rajanayagam, Tamil als politisches Symbol", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 107 (2): 355–356, doi:10.2307/602864

- Subrahmanian, N. (1981), An introduction to Tamil literature, Madras: Christian Literature Society