Rachel Scott

| Rachel Joy Scott | |

|---|---|

|

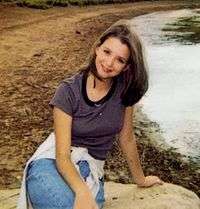

Scott in 1997 | |

| Born |

Rachel Joy Scott August 5, 1981 Denver, Colorado |

| Died |

April 20, 1999 (aged 17) Littleton, Colorado |

| Cause of death | Gunshot wounds to the head and torso.[1] |

| Resting place |

Columbine Memorial Gardens at Chapel Hill Cemetery, Littleton, Colorado, United States 39°35′56.00″N 104°56′43.01″W / 39.5988889°N 104.9452806°WCoordinates: 39°35′56.00″N 104°56′43.01″W / 39.5988889°N 104.9452806°W |

| Occupation | Student |

| Religion | Christianity |

| Website |

www |

Rachel Joy Scott (August 5, 1981 – April 20, 1999) was an American student and the first murder victim of the Columbine High School massacre, which also claimed the lives of 11 other students and a teacher as well as both perpetrators.

She has since been the subject of several books and is the inspiration for Rachel's Challenge, an international[2][3] school outreach program and the most popular school assembly program in America,[4][5] with the objective to advocate Rachel's belief, based on her life, her journals, and the contents of a two-page essay penned just a month before her murder entitled My Ethics; My Codes of Life[6] which had advocated Rachel's belief in compassion being "the greatest form of love humans have to offer."[7]

Owing to the fact both Rachel Scott and Anne Frank died at a young age through the intolerance and hatred of others, and that both girls had written of their wishes to change the world for the better through the simple acts of love and kindness,[8][9] parallels have been drawn between the journals Rachel Scott had written in her short lifespan and Anne Frank's The Diary of a Young Girl.[10]

Early life

Childhood

Rachel Joy Scott was born on August 5, 1981, in Denver, Colorado. She was the third of five children born to Darrell Scott (b. 1949) and Beth Nimmo (b. 1953). Her older sisters are Bethanee (b. 1975) and Dana (b. 1976), and her two younger brothers are Craig (b. 1983) and Mike (b. 1984). Scott's entire family are devout Christians.[11] Her father, Darrell, had formerly been a pastor at a church in Lakewood, Colorado, and worked as a sales manager for a Denver-based food company, whereas her mother, Beth, was a homemaker. Rachel's parents divorced in 1988, but maintained a cordial relationship to one another,[12] and the couple held joint custody of their children.[13][14] The following year, Beth and her children relocated to Littleton, Colorado, where she remarried in 1995.[12]

As a child, Rachel was an energetic, sociable girl, who displayed concern for the well-being of others—particularly if they were downcast or otherwise in need.[15] She also developed a passion for both photography and poetry at an early age. Rachel attended Dutch Creek Elementary School, and subsequently Ken Caryl Middle School, before enrolling in Columbine High School in her 9th grade year. At Columbine, she was an attentive, above average student who displayed a flair for music, acting, drama, and debate. As such, she was a member of the school's forensics and drama clubs,[16] although initially, acting did not come easy to her, and she had to devote extra effort to succeed in this activity.[17]

Coincidentally, via her involvement in the school theater production club, she became acquainted with Dylan Klebold—one of the perpetrators of the Columbine High School massacre—in 1998.[18] Initially, Rachel had offered her friendship to Klebold, who reportedly became privately infatuated with her.[19] On one occasion in 1998, as Rachel performed a mime act to Ray Boltz's Christian song "The Hammer", the audio equipment had faltered midway through her performance, and Rachel had to perform her routine in silence for almost two minutes before the sound technician, Dylan Klebold, was able to rectify the malfunctioning equipment. When he had done so and the audio returned, Rachel's performance was entirely in sync with the music, and upon completing her performance, much of the audience applauded her.[20] Klebold would later perform the role of sound technician for a school talent show held just six weeks before the incident, in which Rachel had performed a mime act to the Christian song "Watch the Lamb."[21]

Adolescence

In a March 1993 visit to the church her aunt and uncle attended in Shreveport, Rachel Scott, aged just 11, chose to commit herself to Christianity.[22] Thereafter, she became known among her family and friends as very devout, pious girl, and would convey her love of the Lord and His Son to everyone whom she knew. Occasionally, she would be subjected to mockery by fellow students for her faith, but would bear these slights with fortitude.[23] By April 1998, five of Rachel's closest friends had chosen to both distance themselves from her and tease her because of her increasing commitment to her faith. Rachel documented this fact in a letter to a relative one year to the day before her death. This letter includes the words: "Now that I have begun to walk my talk, they make fun of me. I don't even know what I have done. I don't even have to say anything, and they turn me away. I have no more personal friends at school. But you know what, it's all worth it."[24]

On numerous occasions throughout her adolescence, her family would observe Rachel in prayer both at home and at church. Her mother would later recollect that her daughter would regularly pray on her knees, with her head downward, her hands upon her face, and that often, these particular prayer rituals would bring tears to Rachel's eyes.[25] By the age of 17, Rachel was an attendee of three churches: Celebration Christian Fellowship; Orchard Road Christian Center; and Trinity Christian Center, where she choreographed dances at Sunday service. Scott was also an active member of church youth groups; at the Orchard Road Christian Center, she attended a youth group named "Breakthrough", where she displayed a passionate interest in both evangelism and discipleship.[26] Scott wrote in her journals that, through attending this youth group, her spiritual awareness developed greatly, and she became known as a leading advocate within this group.[27]

As with many adolescents, Rachel struggled with issues relating to self-esteem in her teens, and has been described by her family as being "blind to her own beauty".[17] By the age of 17, Rachel was just 5 ft 1 in in height, and although she remained popular among her peers, she would occasionally resist efforts to attend certain social events with her friends out of fear she would succumb to the temptation of drinking alcohol.[28] Furthermore, although Rachel had held one serious relationship with a boy in her mid-teens, she had opted to end this relationship out of concerns it may develop physically.[29]

Two weeks prior to the shooting, Rachel held a lead role in a drama production titled "Smoke in the Room." Her role in this play was a headstrong[16] character named Valerie; a girl with a sharp wit and kind heart, but who was continually judged in a negative manner by others due to her external appearance. This performance was held on April 2-3, and in preparation for this role, Rachel had trimmed and dyed her shoulder-length hair.[30]

Personality

According to friends, Rachel often chose to wear clothes of a style reflecting her colorful personality, and would occasionally wear eccentric hats, fedoras, or even pajamas to amuse her companions.[31] In addition to her passion for fashion, music and photography, Rachel was an avid viewer of classic movies, and often spoke of her desire to become a renowned Hollywood actress.[32] She is known to have conveyed these aspirations to her family and to have combined her sense of humor into everyday family life via lighthearted gestures such as leaving a message on her family's answering machine in which she stated: "You have reached the residence of Queen Rachel and her servants, Larry, Beth, Dana, Craig, and Michael. If you have anything you'd like them to do for me, please leave a message."[33]

The contents of her six diaries, discovered following her death, revealed her positive, compassionate, and pious outlook on life. Although some of the entries were accounts of her shared experiences with friends, much of the content was devoted to Rachel's endeavors to her life holding the purpose of spreading the message of Christ,[34] and of her efforts to "reach the unreached". Many of these writings were addressed to God. On the cover of one of two journals she had in her possession on the day of her murder (into which a bullet was found lodged) she had written both: "I won't be labelled as average",[35] and "I write not for the sake of glory. Not for the sake of fame. Not of the sake of success. But for the sake of my soul." In other writings, she expressed her efforts to reach these desires through her acts of kindness and compassion.[36] On one occasion, this had included her having written a prayer for one of the perpetrators of the Columbine High School massacre,[37] although both Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold are known to have shunned and ridiculed Rachel for her Christian faith.[38]

At the time of her death, the 17-year-old Columbine High School junior was an aspiring writer and actress, contemplating as to whether she should pursue her life's desires to become an actress or a Christian missionary.[39] She also held plans to visit Botswana, via a Christian outreach program to build homes in the upcoming summer[40] before moving into her own apartment in the fall of 1999.[41]

Death

Rachel Scott was the first individual to be shot in the Columbine High School massacre. She was shot four times while eating lunch with her friend, Richard Castaldo, on the lawn outside the West Entrance of the school. Initially shot in the chest, arm and leg, Rachel was then murdered by a fatal wound to her left temple, reportedly inflicted as she attempted to crawl to safety.[42] Her friend, Richard Castaldo, was himself shot eight times, and permanently paralyzed from his injuries.[43]

Although at least one author questions the actual circumstances surrounding Rachel Scott's final moments,[44] according to several sources, the final and fatal wound Rachel received was inflicted after Eric Harris had approached her as she and Richard Castaldo lay wounded; he had lifted Rachel's head by her hair, before asking Rachel whether she believed in the existence of the Lord, to which she had replied, "You know I do." In response, Harris had replied, "Well, go be with Him", before shooting Rachel in the temple.[26][45] Richard Castaldo (who only survived the attack by feigning death) would recall hearing Rachel weeping as she curled into a ball upon the grass, before hearing a final gunshot as Harris and Klebold approached them.[46]

In total, 13 people were killed and a further 24 were injured. The two perpetrators then committed suicide, raising the final death toll to 15. After the killings, Rachel's car was turned into a flower-shrouded memorial in the adjacent Clement Park after being moved from the school's parking lot by grieving students. A chain link fence was also installed around the vehicle for mourners to attach their tokens of grief such as flowers, crucifixes, teddy bears, and letters of condolence; her vehicle gradually became scarcely visible beneath the gifts left.[31] Rachel's 16-year-old brother, Craig, was also at the school on the day of the massacre; he was in the library where most of the killings occurred, though he survived unharmed, although in addition to losing his sister, two of his close friends, Isaiah Shoels (18) and Matthew Kechter (16), were also murdered. After the two perpetrators had left the library, Craig assisted in evacuating an injured girl, Kacey Ruegsegger (17), from the library after hearing her cries for help.[47] This act likely prevented Ruegsegger from bleeding to death from her injuries.[48]

Two days after the Columbine High School massacre, Craig Scott appeared on the morning television broadcast of the Today Show to conduct an interview with anchorwoman Katie Couric. Also present at this interview was the father of Isaiah Shoels. Couric later recollected this interview as being "one of the most memorable and even spiritual experiences [she] had ever had." Rachel's parents also later appeared on a show with host Maria Shriver, immediately after sharing on their personal choice of forgiveness.[49]

Funeral

Rachel Joy Scott was laid to rest at the Chapel Hill Cemetery on April 24, 1999 following a two-hour service held at the Trinity Christian Center, officiated by the Reverend Bruce Porter.[50] Hers was one of the first funerals of those murdered in the Columbine High School massacre, and was attended by more than 1,000 people including her family, friends, and staff at Columbine High School. The Reverend Porter began this service by addressing the congregation with the simple question, "What has happened to us as a people that this should happen to us?" Shortly thereafter, he would address the solemn crowd with a speech which included references to Rachel's pious character, kind nature and love of her fellow man, before stating: "You have graduated early from this life to a far better one, where there is no sorrow, violence or death."[51] Her friends from the Orchard Road Christian Church Youth Group also sang a song at the service, composed in her honor, entitled "Why Did You Have to Leave?"[52]

Many of Rachel's friends and those to whom she had extended her offer of friendship and support throughout her life also spoke at this service as the theme song My Heart Will Go On was broadcast to the mourners.[53] Those to convey their eulogies included one youth who had been considered an outcast at Columbine High School, who stated: "All my life I prayed that someone would love me and make me feel wanted. God sent me an angel", before staring at Rachel's casket and weeping.[54] Also to speak at this service was Nick Baumgart, whom Rachel had accompanied to the high school prom as his date three days before her murder, and who stated: "A truer friend, you couldn't find. You could be having the worst day of your entire life; all she had to do was smile."[55] Rachel's parents chose not to speak at the service, but issued a statement in which they described their daughter as "a girl whose love of life was constantly reflected in her love and zeal for music, drama, photography, and for her friends."[56]

Prior to her burial, mourners who had known Rachel throughout her life were invited to write messages of condolence upon her ivory white casket.[57] In what was described by an observer as an "achingly beautiful calligraphy of grief", her coffin was adorned with messages of love, gratitude, solemnity and sorrow.[52]

The funeral service was televised worldwide upon numerous national and international TV channels, and the entirety of her funeral was viewed by millions worldwide. Broadcast live upon CNN, Scott's funeral drew the greatest number of viewers this network had received up to that point, surpassing even the 1997 funeral of Diana, Princess of Wales.[58][59] The mime "Watch the Lamb" was also performed at this service by the girl who had previously taught the recitation to Rachel, who had in turn delivered the performance in 1998.[60]

Legacy

Journal entries

Rachel Scott first received a journal as a Christmas present from her mother in 1997.[61] On that very day, upon the first page of this journal, Rachel had written a message to the Lord in the form of a prayer, thanking Him for her life, for the birth of His Son, and for her family and friends. This first journal entry vividly expresses Rachel's deep love of Jesus Christ.[61] She would regularly populate successive journals with her thoughts and life experiences over the following 16 months, often composing her writing directly to Jesus, whom she repeatedly referred to in these entries as her "best friend".[62] These successive journal entries would also include numerous poems, drawings, and prayers, in addition to accounts of her efforts to welcome new students to her school, and of her offers of friendship to students who had been considered outcasts; those regularly subjected to mockery because of ailments or a handicap; and others she encountered both inside and outside of her school who were generally lonely or in need. Rachel would offer her continued support to all these individuals, and would willingly meet or converse with them to convey her continued friendship and support.[63]

Many of Rachel's later journal entries also reflected a sense of foreboding as to her own impending death. One such journal entry dating from May 1998 had attested to her belief she was to die within a year; this entry had included content indicating Rachel's belief she had accomplished all that she could in her lifespan and ended with these words: 'This will be my last year, Lord. I've gotten what I can. Thank you for the light you put in me.'[64]

The final journal entry Rachel made was a drawing of her own eyes shedding 13 tears upon a rose identical to one that she had previously drawn sprouting from a single columbine flower.[65] The drawing was made as Rachel attended her final class before meeting Richard Castaldo to eat lunch on the lawn outside the West Entrance to Columbine High School.[64][66]

My Ethics; My Codes of Life

One month before her death, Rachel had written a school essay entitled My Ethics; My Codes of Life in which she had stated her belief in the act of compassion being the greatest form of love that human beings could advocate to each other and her efforts to look for the beauty in everyone she encountered in her life. In this essay, Rachel had also written: "My definition of compassion is forgiving, loving, helping, leading, and showing mercy for others. I have this theory that if one person can go out of their way to show compassion then it will start a chain reaction of the same. People will never know how far a little kindness can go."[67]

"I am sure that my codes of life may be very different from yours, but how do you know that trust, compassion, and beauty will not make this world a better place to be in and this life a better one to live? My codes may seem like a fantasy that can never be reached, but test them for yourself, and see the kind of effect they have in the lives of people around you. You just may start a chain reaction."

Closing paragraph of Rachel Scott's essay My Ethics; My Codes of Life, penned just one month before her death.[68]

Upon reading the essay and the journals Rachel had populated in the final 16 months of her life, Rachel's father was inspired to found Rachel's Challenge two years after her death.[69] Several sources of inspiration further motivated Darrell Scott to make this decision. These included a phone call he received from a prosperous businessman named Frank Amedia in which Amedia informed Darrell of his repeatedly praying for the welfare of he and his family since Rachel's death, and of his conviction the Lord held plans for him (Darrell) to speak to leaders and young people across the nation. Amedia further emphasized his willingness to lend his financial support whatever cause he (Amedia) held conviction the Lord held for Darrell.[70] Amedia then proceeded to describe a recurring dream he had been experiencing of Rachel's eyes shedding several tears in a "watering" manner upon an unknown object. At the time of this conversation, Darrell Scott informed Amedia the dream did not seem symbolic to him; however, several days later, Darrell was authorized to collect Rachel's backpack from the sheriff's office. Inside the backpack were the two journals Rachel had in her possession at the time of her murder. Upon viewing the final page Rachel had populated in her last journal, Darrell was stunned to see his daughter's drawing of her own eyes shedding 13 clear tears upon a rose shedding bloodlike droplets. This rose was identical to the one she had drawn in a previous journal, sprouting from a single columbine flower, and besides this drawing, she had drawn a cross inscribed with the words: "Greater love hath no man than this, that a man would lay down his life for his friends!"[71]

Rachel's Tears

Reviewing their daughter's life and hearing firsthand just how profound an impact Rachel's simple acts of kindness had imprinted on the lives of those who had known her in addition to recalling Rachel's repeatedly stated desire for her life to have an impact for the better upon others,[72] Darrell Scott and Beth Nimmo were inspired to write the book Rachel's Tears; a non-fiction book focusing upon their daughter, her faith, the inspirational journal entries she had left, and the impact of her loss upon their lives. The book was published on the first anniversary of Rachel's death, and is incorporated into the Rachel's Challenge program.

Darrell Scott and Beth Nimmo would also subsequently publish two further books directly inspired by their daughter and her legacy: Rachel Smiles: The Spiritual Legacy of Columbine Martyr Rachel Scott, and The Journals of Rachel Joy Scott: A Journey of Faith at Columbine High. The books would be published in 2001 and 2002 respectively. Both parents have expressed their hope that those who did not know their daughter would find inspiration via the principles in how Rachel had lived her life in the books.[49]

Rachel's Challenge

Rachel's Challenge is a national non-profit and non-political organization[73] whose stated aims are to advocate a safe and positive climate and culture in schools in a campaign to quell school violence, bullying, discrimination, and both homicidal and suicidal thoughts in school students. Through the more than 50 designated orators and the subsequent international expansion of Rachel's Challenge,[74] the annual international student outreach of Rachel's Challenge is estimated to be in excess of two million.[75] The program itself typically involves a one-hour audio and video presentation, hosted by the Rachel's Challenge orator, to assembled students, with the stated aim to motivate those present to analyze how they treat others. The orators within Rachel's Challenge include Darrell, Craig and Mike Scott; guest speakers include Nicole Nowlen, who had herself been wounded at age 16 in the Columbine High School massacre,[76][77] and Adam Kyler, a former Columbine student who had harbored suicidal thoughts until Rachel, noting his being the victim of bullying, had offered her continued friendship and support.[78]

Each attendee is asked to pledge to accept the five principles discussed throughout the presentation before leaving the assembly: To eliminate any form of prejudice from their being, and seek only the best in others; to keep a journal and seek to achieve accomplishments; to choose to accept only positive influences in their lives;[79] to commit to bringing a positive change in their home, school, and community through kind words, and undertaking tasks great and small; and to show care and compassion to those who are vulnerable, ridiculed, or in any form of need.[80] A final impetus is to commit to Rachel's theory of the formation of a chain reaction through these five pledges by sharing these commitments with their family members, friends, and peers.[69]

At the close of the program, the audience are asked to close their eyes, and picture five or six people closest to them; they are then asked to tell these individuals how much they mean to them.[81] This initial presentation is followed by a 45-minute, interactive training session involving both adult and student leaders, with the stated objective being that the recipients of this training session perpetuate the chain reaction of kindness envisioned by Rachel.[68] The school in question at which the orator has spoken is also provided with a curriculum and training manual to ensure the continuity of the objectives of Rachel's Challenge, and the orator will later typically hold a meeting with parents and community leaders.[82]

Internationally, many schools have incorporated Rachel's Challenge into their internal character building programs, with active efforts made to eradicate any sense of alienation among the student population, and various initiatives implemented to increase cohesion. One initiative implemented in schools to achieve this objective is to establish a Friends of Rachel club, to sustain the campaign's goals on an ongoing basis.[83] In addition, many students actively seek to honor Rachel's theory of just one person displaying compassion having the potential to spark a chain reaction of the same by spreading her message of kindness, empathy and compassion with their fellow students.[81]

As a direct result of Rachel's Challenge, numerous child and teenage suicides have been prevented,[84] bullying has decreased in American schools, documented acts of community service have increased,[85] and in seven known cases,[86] planned school shootings have been prevented.[87]

National recognition

Rachel Joy Scott was posthumously awarded the 2001 National Kindness Award for Student of the Year by the Acts of Kindness Association in recognition of her endeavors to eradicate negativity, discord, and alienation within those whom she had encountered in her lifespan and to supersede such negative influences with care and compassion.[89]

Craig Scott was formally invited to address a National Council on issues relating to safety and security in schools in the wake of the 2006 Amish school shooting. This meeting was held at the White House before President George W. Bush, White House staff, and educators from across the nation, and focused upon cultural issues and the accomplishments and personal experiences garnered via Rachel's Challenge. President Bush requested a copy of the speech, and Craig Scott would later be invited back to the White House to speak further on these issues.

In a direct recognition of the significant, ongoing, national benefits achieved in schools, colleges, and universities via Rachel's Challenge, the National Education Association of New York awarded Darrell Scott and Rachel's Challenge the Friend of Education Award in 2006.[90] Moreover, in a further national recognition of his selfless dedication toward preserving his daughter's memory in a positive national manner via Rachel's Challenge, Darrell Scott was selected as the 2009 winner of the "All-Stars Among Us" initiative. Along with 29 other recipients, Scott was formally honored as part of the 2009 Major League Baseball All-Star Game ceremonies, held in St. Louis, Missouri, on July 14 that year.[91][92] At this ceremony, Darrell Scott stated: "Rachel loved to watch baseball. She had no clue that because of her memory [...] I'd be here representing her."[91] Both of Rachel's parents have also spoken with renowned entertainers, world leaders, and notable historical individuals such as Miep Gies (one of the individuals who had shielded Anne Frank and her family from the Nazis and had preserved Anne's diary after her capture).[93]

Darrell Scott has stated that repeatedly reliving his daughter's death via his Rachel's Challenge speeches is naturally painful for him, but that he and his family consider the opportunity to be a worthwhile experience in which they can turn a tragedy into triumph,[94] stating: "I feel that God has really called me to do this. To pick up the torch my daughter dropped. This is what my daughter would have wanted to see. If I died right now, I can tell you my daughter's prayer has been answered."[95] Rachel's mother would herself recollect on the 10th anniversary of her daughter's passing: "Only through eternal eyes will she ever know how powerful her life and death became."[62]

Media

Film

- The film I'm Not Ashamed (2016) is directly based upon the life, death, and legacy of Rachel Joy Scott. Directed by Brian Baugh and starring Masey McLain as Rachel Scott, I'm Not Ashamed is directly based upon the contents of Scott's journals.

Bibliography

- Nimmo, Beth; Klingsporn, Debra (2000). Rachel's Tears: The Spiritual Journey of Columbine Martyr Rachel Scott. Thomas Nelson Inc. ISBN 978-0-7852-6848-2

- Nimmo, Beth; Klingsporn, Debra (2001). The Journals of Rachel Joy Scott: A Journey of Faith at Columbine High. Thomas Nelson Inc. ISBN 978-1-4041-7560-0

- Scott, Darrell; Rabey, Steve (2001). Chain Reaction: A Call to Compassionate Revolution. Thomas Nelson Inc. ISBN 0-7852-6680-1

- Scott, Darrell; Rabey, Steve (2002). Rachel Smiles: The Spiritual Legacy of Columbine Martyr Rachel Scott. Thomas Nelson Inc. ISBN 978-0-7852-9688-1

- Scott, Darrell; Rabey, Steve (2009). Rachel's Tears: 10 Years after Columbine, Rachel Scott's Faith Lives on. Thomas Nelson Inc. ISBN 978-1-4003-1347-1

Television

- The 49-minute documentary, Ambassador of Kindness is directly based on the evolution of Rachel's Challenge following Rachel Scott's murder. Directed by Bryan Boorujy and Janet Stumbo, Ambassador of Kindness was released in 2012.

- Columbine's Witness: The Story of Rachel Scott is a 2010 documentary focusing on the life and legacy of Rachel Scott. Members of Rachel's family, her friends, and faculty members of Columbine High School are among those interviewed for this documentary.

See also

References

- ↑ acolumbinesite.com/autopsies

- ↑ "'Rachel's Challenge' promotes little acts of kindness among Calgary kids". globalnews.ca. 2014-05-15. Retrieved 2016-09-23.

- ↑ "Sharing her pain to help stop bullying". royalgazette.com. 2016-02-04. Retrieved 2016-09-23.

- ↑ "Speaker challenges for positive impact". The Wahkiakum County Eagle. January 17, 2008. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

- ↑ "Rachel's Challenge - Victim of Columbine High School Shooting". rivertonchamber.org. 2011-09-12. Retrieved 2016-09-28.

- ↑ "Father remembers Columbine victim" (video). Today show. NBC. 20 April 2009. Retrieved 20 April 2009.

- ↑ "Rachel's Story: Darrell Scott brings his daughter's memory to the Shoals". Times Daily. September 15, 2001. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- ↑ "A quote by Anne Frank".

- ↑ "Columbine Victim Rachel Scott's Kindness Lives On". Huffington Post. December 12, 2011. Retrieved September 1, 2016.

- ↑ "The diary of Rachel Scott: Uncle keeps Columbine shooting victim's spirit alive". The Oklahoman. October 31, 2007. Retrieved September 1, 2016.

- ↑ The Journals of Rachel Scott: A Journey of Faith at Columbine High p. 12

- 1 2 Beth Nimmo and Darrell Scott (2000). Rachel's Tears—The Spiritual Journey of Columbine Martyr Rachel Scott. Nashville, Tenn.: Thomas Nelson Publishers. pp. 57, 61, 173. ISBN 0-7852-6848-0.

- ↑ Rachel's Tears, p. 32

- ↑ S.C. Gwynne (1999-12-20). "An Act of God?". Time magazine. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ "About Us: Meet Rachel". rachelschallenge.org. 2010-08-06. Retrieved 2016-09-17.

- 1 2 "Rachel Scott". The Denver Post. April 23, 1999. Retrieved September 14, 2016.

- 1 2 Rachel's Tears, p. 46

- ↑ "Rachel Joy Scott". Acolumbinesite.com. 1981-08-05. Retrieved 2012-12-10.

- ↑ "Beth Nimmo Interview". famousinterview.ca. 2009-04-27. Retrieved 2016-10-03.

- ↑ Rachel's Tears: 10th Anniversary Edition: The Spiritual Journey of Columbine p. 94

- ↑ Rachel's Tears: 10th Anniversary Edition: The Spiritual Journey of Columbine p. 93

- ↑ The Journals of Rachel Scott: A Journey of Faith at Columbine High p. 3

- ↑ Rachel's Tears: 10th Anniversary Edition: The Spiritual Journey of Columbine p. 117

- ↑ Rachel's Tears: 10th Anniversary Edition: The Spiritual Journey of Columbine p. 96

- ↑ The Journals of Rachel Scott: A Journey of Faith at Columbine High p. 27

- 1 2 "Pentecostal Evangel".

- ↑ Rachel's Tears: 10th Anniversary Edition: The Spiritual Journey of Columbine p. 117

- ↑ Rachel's Tears, p. 48

- ↑ Rachel's Tears, p. 45

- ↑ "Rachel Joy Scott". acolumbinesite.com. 1981-08-05. Retrieved 2016-09-14.

- 1 2 "Friends tell victim goodbye". Daily News. April 25, 1999. Retrieved September 10, 2016.

- ↑ "Rachel Scott touched 'millions of people's lives". Hollis Brookline Journal. April 15, 2008. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ↑ "United They Stand". people.com. 1999-05-10. Retrieved 2016-10-08.

- ↑ Shepard, C. "Rachel Joy Scott".

- ↑ Rachel's Tears: 10th Anniversary Edition: The Spiritual Journey of Columbine p. 174

- ↑ "Preserving A Daughter's Spirit". CBS News. 2000-04-20. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

- ↑ "In the Face of Death: Craig Scott Revisits the Columbine Shooting". CBN.com. 2002-07-22. Retrieved 2016-09-06.

- ↑ "Beth Nimmo Interview". famousinterview.ca. 2009-04-27. Retrieved 2016-10-01.

- ↑ "Columbine Victim's Dad Traveling to Share his Daughter's Journal". Toledo Blade. November 27, 1999. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ↑ "Victims in High School had Big Dreams, Plans for Future". Times Daily. April 23, 1999. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- ↑ "Rachel's Joy Lives On". denverpost.com. 1999-04-25. Retrieved 2016-09-23.

- ↑ "A Columbine Site: Rachel Joy Scott". acolumbinesite.com. 2000-04-20. Retrieved 2016-09-25.

- ↑ Rachel's Tears: 10th Anniversary Edition: The Spiritual Journey of Columbine pp. 91-92

- ↑ The Martyrs of Columbine: Faith and the Politics of Tragedy pp. 141-142

- ↑ "Craig Scott; Columbine Massacre Survivor, Revisits the High School and Remembers his Murdered Sister Rachel Scott". Huffington Post. April 10, 2013. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

- ↑ "Through the Eyes of Survivors". denverpost.com. 2015-06-13. Retrieved 2016-09-25.

- ↑ Rachel's Tears: 10th Anniversary Edition: The Spiritual Journey of Columbine p. 11

- ↑ "Columbine survivor in Rose Parade". Casper Star Tribune. December 27, 2004. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- 1 2 "Remembering Columbine victim Rachel Scott". today.com. 2009-04-20. Retrieved 2016-09-29.

- ↑ "Littleton Funeral". Rome News-Tribune. April 25, 1999. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ↑ "Terror in Littleton: the Details; Attack at School Planned a Year, Authorities Say". New York Times. April 25, 1999. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- 1 2 "Heart-wrenching Farewells Begin In Grieving Town". Chicago Tribune. April 25, 1999. Retrieved September 3, 2016.

- ↑ Rachel's Tears, p. 105

- ↑ "Heart-wrenching Farewells Begin In Grieving Town". Chicago Tribune. April 25, 1999. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- ↑ "A Shared Grief". Los Angeles Times. April 24, 1999. Retrieved September 3, 2016.

- ↑ "Friends, Family Mourn 4 Beloved Teens". The Denver Post. April 24, 1999. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- ↑ "Terror In Littleton: The Details; Attack at School Planned a Year, Authorities Say". The New York Times. April 25, 1999. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- ↑ Shepard, C. "~(@)~ 4-20-99 a Columbine site ~(@)~ All about the Columbine High School shootings".

- ↑ "17-year-old girl 'shined for God at all times'", Rocky Mountain News

- ↑ Rachel's Tears: 10th Anniversary Edition: The Spiritual Journey of Columbine p. 94

- 1 2 Rachel's Tears: 10th Anniversary Edition: The Spiritual Journey of Columbine p. xxi

- 1 2 "Who was I before April 20, 1999?". lfcnews.com. 2009-04-18. Retrieved 2016-10-07.

- ↑ Rachel's Tears: 10th Anniversary Edition: The Spiritual Journey of Columbine p. 95

- 1 2 "Rachel's Challenge builds character compassion". The Othello Outlook. October 15, 2007. Retrieved August 30, 2016.

- ↑ "13 Years And 13 Tears Later – Remembering Columbine's Rachel Scott". verticallivingministries.com. 2012-04-20. Retrieved 2016-09-02.

- ↑ "Scott: On the road to tell Rachel's faith story". The Free Lance-Star. December 20, 1999. Retrieved August 30, 2016.

- ↑ Scott, Rachel (1999). "My Ethics, My Codes of Life". Rachel's Challenge. Archived from the original on May 1, 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- 1 2 "Rachel's Challenge: One Story Changing the Lives of Millions". slidetosafety.com. 2009-10-30. Retrieved 2016-09-22.

- 1 2 "Speaker challenges for positive impact". The Wahkiakum County Eagle. January 17, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2016.

- ↑ Rachel's Tears: 10th Anniversary Edition: The Spiritual Journey of Columbine p. 173

- ↑ Rachel's Tears: 10th Anniversary Edition: The Spiritual Journey of Columbine pp. 175-177

- ↑ "Rachel Scott touched 'millions of people's lives". Hollis Brookline Journal. April 15, 2008. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- ↑ Grey, Jamie (5 August 2014). "Rachel's Challenge to offer small school programs". KTVB.com. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ↑ "Rachel's Challenge: Preventing Teen Violence". districtadministration.com. 2010-11-01. Retrieved 2016-09-18.

- ↑ Rachel's Challenge: Media Fact Sheet

- ↑ "Columbine Survivor Shares Message of Kindness with Tokay High". The Lodi News-Sentinel. November 29, 2007. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Columbine Victim's Legacy Lives On". The Quincy Valley Post-Register. January 11, 2007. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

- ↑ Gelbwasser, Michael (December 2, 2009). "Links in Chain of Kindness". The Sun Chronicle.com. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- ↑ "Rachel Scott touched 'millions of people's lives'". Hollis Brookline Journal. February 15, 2008. Retrieved September 14, 2016.

- ↑ "Rachel's Challenge: One Story Changing the Lives of Millions - Slide To Safety". 30 October 2015.

- 1 2 "Rachel's challenge brings character compassion". The Othello Outlook. October 4, 2007. Retrieved September 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Rachel's Challenge Community Event: A Challenge of Kindness - MilfordNow". 22 January 2015.

- ↑ "The Scoop: May Issue". Midlothian Scoop. 2012-05-01. Retrieved 2016-09-26.

- ↑ "Students take challenge". Bedford Journal. February 14, 2008. Retrieved September 2, 2016.

- ↑ "About Us - Rachel's Challenge".

- ↑ "Major League Baseball honors off-field all-stars". usatoday.com. 2009-07-14. Retrieved 2016-09-18.

- ↑ "Rachel's Challenge Program at Grafton High School November 20th". Valley News and Views. November 15, 2007. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- ↑ President Bush Participates in Panel on School Safety: thewhitehouse.gov

- ↑ "Rachel's Challenge sets Kindness in Motion". priestrivertimes.com. 2009-02-11. Retrieved 2016-09-23.

- ↑ "Rachel's Challenge Program at Grafton High School November 20th". Valley News and Views. November 15, 2007. Retrieved August 30, 2016.

- 1 2 Singer, Tim (June 29, 2009). "Scott is Rockies' All-Star Among Us". mlb.com. Retrieved 2009-07-14.

- ↑ Newman, Mark (July 14, 2009). "Obama kicks off historic night in St. Louis". mlb.com. Retrieved 2009-07-15.

- ↑ "Inspriational people - and some others". The Times Herald. November 16, 2010. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ↑ Rachel's Tears: 10th Anniversary Edition: The Spiritual Journey of Columbine p. 179

- ↑ "Scott: On the Road to tell Rachel's Faith Story". The Free Lance-Star. December 20, 1999. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

Cited works and further reading

- Brown, Brooks; Merritt, Robert (2002). No Easy Answers: The Truth Behind Death at Columbine High School. Lantern Books. ISBN 1-590-56031-0.

- Cullen, David (2009). Columbine. Grand Central Publishing. 978-0-4465-4693-5

- Keuss, Jeff; Sloth, Lia (2006). Rachel's Challenge: A Columbine Legacy. Positively for Kids. ISBN 978-0-9765-7225-1.

- Larkin, Ralph (2007). Comprehending Columbine. Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1-5921-3490-8.

- Marsico, Katie (2010). The Columbine High School Massacre: Murder in the Classroom. Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 978-0-7614-4985-0.

- Scott, Darrell; Nimmo, Beth (2000). The Journal of Rachel Scott: A Journey of Faith at Columbine High. Thomas Nelson Inc. ISBN 0-849-97594-8.

- Scott, Darrell; Nimmo, Beth; Rabey, Steve (2009). Rachel's Tears: 10th Anniversary Edition: The Spiritual Journey of Columbine. Thomas Nelson Inc. ISBN 978-1-4003-1347-1.

- Scott, Darrell; Rabey, Steve (2001). Chain Reaction: A Call to Compassionate Revolution. Thomas Nelson Publishers. ISBN 0-785-26680-1.

- Watson, Justin (2002). The Martyrs of Columbine: Faith and the Politics of Tragedy. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-7000-8.

External links

- Contemporary news article detailing the funeral of Rachel Scott

- A Columbine Site: A website dedicated to those murdered, injured, and affected in the Columbine High School massacre

- Rachel's entry at A Columbine Site

- Official presentation video detailing the objectives and impact of Rachel's Challenge

- My Ethics; My Codes of Life, as written by Rachel Scott one month before her death

- Rachel Joy Scott at Find a Grave

- Official website of I'm Not Ashamed

- Official website of Rachel's Challenge