Regenerative circuit

The regenerative circuit (or regen) allows an electronic signal to be amplified many times by the same active device. It consists of an amplifying vacuum tube or transistor with its output connected to its input through a feedback loop, providing positive feedback.[1][2][3] This circuit was widely used in radio receivers, called regenerative receivers, between 1915 and World War II.[3] The regenerative receiver was invented in 1912[4] and patented in 1914[5] by American electrical engineer Edwin Armstrong when he was an undergraduate at Columbia University.[6] Due partly to its tendency to radiate interference,[3][2] by the 1930s the regenerative receiver was superseded by other receiver designs, the TRF and superheterodyne receivers[7] and became obsolete,[2][8] but regeneration (now called positive feedback) is widely used in other areas of electronics, such as in oscillators and active filters.

A receiver circuit that used regeneration in a more complicated way to achieve even higher amplification, the superregenerative receiver, was invented by Armstrong in 1922.[8][2][1] It was never widely used in general receivers, but due to its small parts count is used in a few specialized low data rate applications,[8] such as garage door openers,[9] wireless networking devices,[8] walkie-talkies and toys.

Operation

The gain of any amplifying device, such as a vacuum tube, transistor, or op amp, can be increased by feeding some of the energy from its output circuit back into its input with positive feedback. This is called regeneration. Because of the large amplification possible with regeneration, regenerative receivers often use only a single amplifying element (tube or transistor). In a regenerative receiver the output of the tube or transistor is connected to its input through a feedback loop with a tuned circuit (LC circuit) as a filter in it. The tuned circuit allows positive feedback only at its resonant frequency. The tuned circuit is also connected to the antenna and serves to select the radio frequency to be received, and is adjustable to tune in different stations. The feedback loop also has a means of adjusting the amount of feedback (the loop gain). For AM signals, the tube may also function as a detector that recovers the audio modulation; when that is done, the circuit is also called a regenerative detector.

AM reception

For AM reception, the gain of the loop is adjusted so it is just below the level required for oscillation (a loop gain of just less than one). The result of this is to greatly increase the gain of the amplifier at the bandpass frequency (resonant frequency), while not increasing it at other frequencies. So the incoming radio signal is amplified by a large factor, 103 - 105, increasing the receiver's sensitivity to weak signals. The high gain also has the effect of sharpening the circuit's bandwidth (increasing the Q factor) by an equal factor, increasing the selectivity of the receiver, its ability to reject interfering signals at frequencies near the desired station's frequency.[10]

CW reception (autodyne mode)

For the reception of CW radiotelegraphy (Morse code) signals, the feedback is increased to the level of oscillation (a loop gain of one), so that the amplifier functions as an oscillator (BFO) as well as an amplifier, generating a steady sine wave signal at the resonant frequency, as well as amplifying the incoming signal. The tuned circuit is adjusted so the oscillator frequency is a little to one side of the signal frequency. The two frequencies mix in the nonlinear amplifier, generating a heterodyne (beat frequency) signal at the difference between the two frequencies. This frequency is in the audio range, so it is heard as a steady tone in the receiver's speaker whenever the station's carrier is present. Morse code is transmitted by keying the transmitter on and off, producing different length pulses of carrier ("dots" and "dashes"). The audio tone makes the carrier pulses audible, and they are heard as "beeps" in the speaker.

SSB reception

For the reception of single-sideband (SSB) signals, the circuit is also set to oscillate. The BFO signal is adjusted to one side of the incoming signal, and functions as the replacement carrier needed to demodulate the signal.

Advantages and disadvantages

Regenerative receivers require fewer components than other types of receiver circuit. The circuit's original attraction was that it got more amplification (gain) out of the expensive vacuum tubes of early receivers, thus requiring fewer stages of amplification. Early vacuum tubes had low gain at radio frequencies (RF). Therefore, the TRF receivers used before regenerative receivers often required 5 or 6 tubes, each stage requiring tuned circuits that had to be tuned in tandem to bring in stations, making the receiver cumbersome, power hungry, and hard to adjust. Regenerative receivers, by contrast, could often get adequate gain with one tube. In the 1930s the regenerative receiver was replaced by the superheterodyne circuit in commercial receivers due to its superior performance and the falling cost of tubes. Since the advent of the transistor in 1946, the low cost of active devices has removed most of the advantage of the circuit. However, in recent years the regenerative circuit has seen a modest comeback in receivers for low cost digital radio applications such as garage door openers, keyless locks, RFID readers and some cell phone receivers.

Regeneration can increase the gain of an amplifier by a factor of 15,000 or more.[11] This is quite an improvement, especially for the low-gain vacuum tubes of the 1920s and early 1930s. The type 236 triode (US vacuum tube, obsolete since the mid-1930s) had a non-regenerative voltage gain of only 9.2 at 7.2 MHz, but in a regenerative detector, had voltage gain as high as 7900. In general, "... regenerative amplification was found to be nearly directly proportional to the non-regenerative detection gain." "... the regenerative amplification is limited by the stability of the circuit elements, tube [or device] characteristics and [stability of] supply voltages which determine the maximum value of regeneration obtainable without self-oscilation."[12] Intrinsically, there is little or no difference in the gain and stability available from vacuum tubes, JFET's, MOSFET's or bipolar junction transistors (BJT's).

A disadvantage of this receiver is that the regeneration (feedback) level must be adjusted when it is tuned to a new station. This is because the regenerative detector has less gain with stronger signals, and because the stronger signals cause the tube or transistor to operate on a different section of its amplification curve (i.e. grid V vs. plate V for tubes; gate V vs drain V for FET's, and base current vs. collector current for BJT's).

A drawback of early vacuum tube designs was that, when the circuit was adjusted to oscillate, it could operate as a transmitter, radiating an RF signal from its antenna at power levels as high as one watt. So it often caused interference to nearby receivers. Modern circuits using semiconductors, or high-gain vacuum tubes with plate voltage as low as 12V, typically operate at milliwatt levels—one thousand times lower. So interference is far less of a problem today. In any case, adding a preamp stage (RF stage) between the antenna and the regenerative detector is often used to further lower the interference.

Other shortcomings of regenerative receivers are the presence of a characteristic noise (“mush”) in their audio output, and sensitive and unstable tuning. These problems have the same cause: a regenerative receiver’s gain is greatest when it operates on the verge of oscillation, and in that condition, the circuit behaves chaotically.[13][14][15] Simple regenerative receivers lack an RF amplifier between the antenna and the regenerative detectors, so any change with the antenna swaying in the wind, etc. can change the frequency of the detector.

A major improvement in stability and a small improvement in available gain is the use of a separate oscillator, which separates the oscillator and its frequency from the rest of the receiver, and also allows the regenerative detector to be set for maximum gain and selectivity - which is always in the non-oscillating condition.[11] A separate oscillator, sometimes called a BFO (Beat Frequency Oscillator) was known from the early days of radio, but was rarely used to improve the regenerative detector. When the regenerative detector is used in the self-oscillating mode, i.e. without a separate oscillator, it is known as an "autodyne".

History

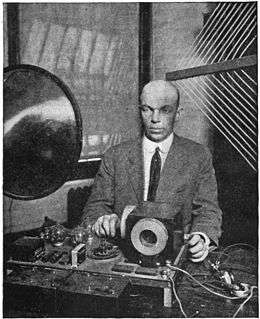

The inventor of FM radio, Edwin Armstrong, invented and patented the regenerative circuit while he was a junior in college, in 1914.[16] He patented the superregenerative circuit in 1922, and the superheterodyne receiver in 1918.

Lee De Forest filed a patent in 1916 that became the cause of a contentious lawsuit with the prolific inventor Armstrong, whose patent for the regenerative circuit had been issued in 1914. The lawsuit lasted twelve years, winding its way through the appeals process and ending up at the Supreme Court. Armstrong won the first case, lost the second, stalemated at the third, and then lost the final round at the Supreme Court.[17][18]

At the time the regenerative receiver was introduced, vacuum tubes were expensive and consumed lots of power, with the added expense and encumbrance of heavy batteries. So this design, getting most gain out of one tube, filled the needs of the growing radio community and immediately thrived. Although the superheterodyne receiver is the most common receiver in use today, the regenerative radio made the most out of very few parts.

In World War II the regenerative circuit was used in some military equipment. An example is the German field radio "Torn.E.b". Regenerative receivers needed far fewer tubes and less power consumption for nearly equivalent performance.

A related circuit, the superregenerative detector, found several highly-important military uses in World War II in Friend or Foe identification equipment and in the top-secret proximity fuze.

In the 1930s, the superheterodyne design began to gradually supplant the regenerative receiver, as tubes became far less expensive. In Germany the design was still used in the millions of mass-produced German "peoples receivers" (Volksempfänger) and "German small receivers" (DKE, Deutscher Kleinempfänger). Even after WWII, the regenerative design was still present in early after-war German minimal designs along the lines of the "peoples receivers" and "small receivers", dictated by lack of materials. Frequently German military tubes like the "RV12P2000" were employed in such designs. There were even superheterodyne designs, which used the regenerative receiver as a combined IF and demodulator with fixed regeneration. The superregenerative design was also present in early FM broadcast receivers around 1950. Later it was almost completely phased out of mass production, remaining only in hobby kits.

Operating limits

Quality of a receiver is defined by its sensitivity and selectivity. For a single-tank TRF (tuned radio frequency) receiver without regenerative feedback, , where Q is tank "quality" defined as , Z is reactive impedance, R is resistive loss. Signal voltage at tank is antenna voltage multiplied by Q.

Positive feedback compensates the energy loss caused by R, so we may express it as bringing in some negative R. Quality with feedback is . Regeneration rate is .

M depends on stability of amplification and feedback coefficient, because if R-Rneg is set less than Rneg fluctuation, it will easily overstep the oscillation margin. This problem can be partly solved by "grid leak" or any kind of automatic gain control, but the downside of this is surrendering control over receiver to noises and fadings of input signal, which is undesirable. Modern semiconductors may offer more stability than vacuum tubes of the 1920s, depending on other circuit parameters as well.

Actual numbers: To have 3 kHz bandwidth at 12 MHz (short waves travelling all around Earth) we need . A two-inch coil of thick silvered wire wound on a ceramic core may have Q up to 400, but let's suppose . We need , which is attainable with good stable amplifier even without power stabilizing.

Superregenerative receiver

The superregenerative receiver uses a second lower-frequency oscillation (within the same stage or by using a second oscillator stage) to provide single-device circuit gains of around one million. This second oscillation periodically interrupts or "quenches" the main RF oscillation. Ultrasonic quench rates between 30 and 100 kHz are typical. After each quenching, RF oscillation grows exponentially, starting from the tiny energy picked up by the antenna plus circuit noise. The amplitude reached at the end of the quench cycle (linear mode) or the time taken to reach limiting amplitude (log mode) depends on the strength of the received signal from which exponential growth started. A low-pass filter in the audio amplifier filters the quench and RF frequencies from the output, leaving the AM modulation. This provides a crude but very effective automatic gain control (AGC).

Advantages and applications

Superregenerative detectors work well for wide-band signals such as FM, where they perform "slope detection". Regenerative detectors work well for narrow-band signals, especially for CW and SSB which need a heterodyne oscillator or BFO. A superregenerative detector does not have a usable heterodyne oscillator – even though the superregen always self-oscillates, so CW (Morse code)and SSB (single side band) signals can't be received properly.

Superregeneration is most valuable above 27 MHz, and for signals where broad tuning is desirable. The superregen uses many fewer components for nearly the same sensitivity as more complex designs. It is easily possible to build superregen receivers which operate at microwatt power levels, in the 30 to 6,000 MHz range. These are ideal for remote-sensing applications or where long battery life is important. For many years, superregenerative circuits have been used for commercial products such as garage-door openers, radar detectors, microwatt RF data links, and very low cost walkie-talkies.

Because the superregenerative detectors tend to receive the strongest signal and ignore other signals in the nearby spectrum, the superregen works best with bands that are relatively free of interfering signals. Due to Nyquist's theorem, its quenching frequency must be at least twice the signal bandwidth. But quenching with overtones acts further as a heterodyne receiver mixing additional unneeded signals from those bands into the working frequency. Thus the overall bandwidth of superregenerator cannot be less than 4 times that of the quench frequency, assuming the quenching oscillator produces an ideal sine wave.

Patents

- US 1113149, Armstrong, E. H., "Wireless receiving system", published October 29, 1913, issued October 6, 1914

- US 1342885, Armstrong, E. H., "Method of receiving high frequency oscillation", published February 8, 1919, issued June 8, 1920

- US 1424065, Armstrong, E. H., "Signalling system", published June 27, 1921, issued July 25, 1922

- US 2211091, Braden, R. A., "Superregenerative magnetron receiver" 1940.

See also

References

- 1 2 Ellinger, Frank (2008). Radio Frequency Integrated Circuits and Technologies. Springer. pp. 42–43. ISBN 3540693254. Note: Armstrong applied for a patent in 1914 but invented the circuit in 1912.

- 1 2 3 4 Technical Manual TM 11-665: C-W and A-M Radio Transmitters and Receivers. Dept. of the Army, US Government Printing Office. 1952. pp. 187–189.

- 1 2 3 Poole, Ian (1998). Basic Radio: Principles and Technology. Newnes. pp. 187–193. ISBN 0080938469.

- ↑ Hong, Sungook. "A history of the regeneration circuit: From invention to patent litigation" (PDF). Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers. Retrieved March 9, 2014.

- ↑ US Patent 1113149A, Edwin H. Armstrong, Wireless receiving system, filed October 29, 1913, granted October 6, 1914

- ↑ Armstrong, Edwin H. (September 1915). "Some recent developments in the Audion receiver" (PDF). Proc. of the IRE. New York: Institute of Radio Engineers. 3 (9): 215–247. Retrieved August 29, 2012.

- ↑ Malanowski, Gregory (2011). The Race for Wireless: How Radio Was Invented (or Discovered?). AuthorHouse. p. 66. ISBN 1463437501.

- 1 2 3 4 Williams, Lyle Russell (2006). The New Radio Receiver Building Handbook. Lulu. pp. 24–26, 31–32. ISBN 1847285260.

- ↑ Bensky, Alan (2004). Short-range Wireless Communication: Fundamentals of RF System Design and Application. Newnes. p. 1. ISBN 008047005X.

- ↑ The Radio Amateur's Handbook. American Radio Relay League. 1978. pp. 241–242.

- 1 2 Robinson 1933

- ↑ Robinson 1933, p. 29

- ↑ Domine M.W. Leenaerts and Wim M.G. van Bokhoven, “Amplification via chaos in regenerative detectors,” Proceedings of SPIE *, vol. 2612**, pages 136-145 (December 1995). (* SPIE = Society of Photo-optical Instrumentation Engineers; renamed: International Society for Optical Engineering) (** Jaafar M.H. Elmirghani, ed., Chaotic Circuits for Communication -- a collection of papers presented at the SPIE conference of 23–24 October 1995 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.)

- ↑ Domine M.W. Leenaerts, “Chaotic behavior in superregenerative detectors,” IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems Part 1: Fundamental Theory and Applications, vol. 43, no. 3, pages 169-176 (March 1996).

- ↑ In 1922, during his development of the superregenerative receiver, Edwin Armstrong noted signs of chaotic behavior in his circuits. See: Edwin H. Armstrong (1922) "Some recent developments of regenerative circuits," Proceedings of the Institute of Radio Engineers, 10 (8) : 244-260. From p. 252: " … a free oscillation starts every time the resistance of the circuit becomes negative. … The free oscillations produced in the system when no signaling emf. is impressed, must be initiated by some irregularity of operation of the vacuum tubes, … ."

- ↑ "The Armstrong Patent", Radio Broadcast, Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1 (1): 71–72, May 1922

- ↑ Morse 1925, p. 55

- ↑ Lewis 1991

- Lewis, Tom (1991), Empire of the Air: the men who made radio, New York: Edward Burlingame Books, ISBN 0060981199

- Morse, A. H. (1925), Radio: Beam and Broadcast, London: Ernest Benn Limited. History of radio in 1925. Has May 5, 1924, appellate decision by Josiah Alexander Van Orsdel in De Forest v Armstrong, pp 46–55. Appellate court credited De Forest with the regenerative circuit: "The decisions of the Commissioner are reversed and priority awarded to De Forest." p 55.

- Robinson, H. A. (February 1933), "Regenerative Detectors, What We Get From Them - How To Get More", QST, 17 (2): 26–30 & 90

- Ulrich L. Rohde, Ajay Poddar www.researchgate.net/publication/4317999_A_Unifying_Theory_and_Characterization_of_Super-Regenerative_Receiver_(SRR)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Regenerative circuits. |

- Some Recent Developments in the Audion Receiver by EH Armstrong, Proceedings of the IRE (Institute of Radio Engineers), volume 3, 1915, pp. 215–247.

- a one transistor regenerative receiver

- Armstrong v. De Forest Radio Telephone & Telegraph Co. (2nd Cir. 1926) 10 F.2d 727, February 8, 1926; cert denied 270 U.S. 663, 46 S.Ct. 471. opinion on leagle.com

- Armstrong v. De Forest, 13 F.2d 438 (2d Cir. 1926)