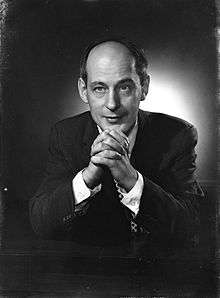

René Lévesque

| René Lévesque GOQ | |

|---|---|

| |

| 23rd Premier of Quebec | |

|

In office November 25, 1976 – October 3, 1985 | |

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Lieutenant Governor |

Hugues Lapointe Jean-Pierre Côté Gilles Lamontagne |

| Preceded by | Robert Bourassa |

| Succeeded by | Pierre-Marc Johnson |

| Leader of the Parti Québécois | |

|

In office October 14, 1968 – September 29, 1985 | |

| Preceded by | none |

| Succeeded by | Pierre-Marc Johnson |

| MNA for Montréal-Laurier | |

|

In office June 22, 1960 – June 5, 1966 | |

| Preceded by | Arsène Gagné |

| Succeeded by | riding abolished |

| MNA for Laurier | |

|

In office June 5, 1966 – April 29, 1970 | |

| Preceded by | riding established |

| Succeeded by | André Marchand |

| MNA for Taillon | |

|

In office November 15, 1976 – December 2, 1985 | |

| Preceded by | Guy Leduc |

| Succeeded by | Claude Filion |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

August 24, 1922 Campbellton, New Brunswick, Canada |

| Died |

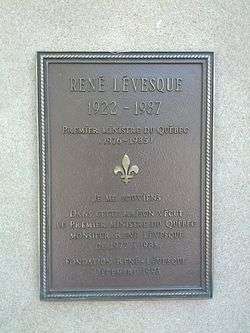

November 1, 1987 (aged 65) Nuns' Island, Quebec, Canada |

| Cause of death | Heart attack |

| Nationality | Canadian |

| Political party |

Parti Québécois (after 1968) Independent (1967–1968) Liberal (1960–1967) |

| Spouse(s) |

Louise L'Heureux 1947–1977 (1921-2012) Corinne Côté 1979–1987 (1943-2005) |

| Profession | Journalist |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

René Lévesque[1] (GOQ; Quebec French pronunciation: [ʁœne leˈvaɪ̯k]; August 24, 1922 – November 1, 1987) was a reporter, a minister of the government of Quebec (1960–1966), the founder of the Parti Québécois political party and the 23rd Premier of Quebec (November 25, 1976 – October 3, 1985). He was the first Quebec political leader since Confederation to attempt, through a referendum, to negotiate the political independence of Quebec. Lévesque was born in the Hotel Dieu Hospital in Campbellton, New Brunswick and raised 133 km away in New Carlisle, Quebec, on the Gaspé peninsula, by his parents, Diane (née Dionne) and Dominic Lévesque, a lawyer.[2]

Early life

Lévesque was born in Campbellton, New Brunswick on August 24, 1922. He was the son of Dominic and Diane Lévesque. He had three siblings, André, Fernand and Alice. His father died when Lévesque was 14 years old.[3]

Journalist

Lévesque attended the Séminaire de Gaspé and the Saint-Charles-Garnier College in Quebec City, both of which were run by the Jesuits. He studied for a law degree at Université Laval in Quebec City, but left the university in 1943 without having completed the degree.[4] He worked as an announcer and news writer at the radio station CHNC in New Carlisle, as a substitute announcer for CHRC during 1941 and 1942, and then at CBV in Quebec City.[4]

During 1944–1945, he served as a liaison officer and war correspondent for the U.S. Army in Europe. He reported from London while it was under regular bombardment by the Luftwaffe, and advanced with the Allied troops as they pushed back the German army through France and Germany. Throughout the war, he made regular journalistic reports on the airwaves and in print. He was with the first unit of Americans to reach Dachau concentration camp.[4]

In 1947, he married Louise L'Heureux, with whom he would have two sons and a daughter.[5] Lévesque worked as a reporter for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation's French Language section in the international service. He again served as a war correspondent for CBC in the Korean War in 1952. After that, he was offered a career in journalism in the United States, but decided to stay in Quebec.[6]

From 1956 to 1959, Lévesque became famous in Quebec for hosting a weekly television news program on Radio-Canada called Point de Mire.[4]

Lévesque covered international events and major labour struggles between workers and corporations that dogged the Union Nationale government of premier Maurice Duplessis culminating with a massive strike in 1957 at the Gaspé Copper Mine in Murdochville. The Murdochville strike was a milestone for organized labour in Quebec as it resulted in changes to the province's labour laws.

While working for the public television network, he became personally involved in the broadcasters' strike that lasted 68 tumultuous days beginning in late 1958. Lévesque was arrested during a demonstration in 1959, along with union leader Jean Marchand and 24 other demonstrators.

Public figure

In 1960, Lévesque entered politics as a star candidate and was elected to the Legislative Assembly of Quebec in the 1960 election as a Liberal Party member in the riding of Montréal-Laurier. In the government of Jean Lesage, he served as Minister of Hydroelectric Resources and Public Works from 1960 to 1961, and Minister of Natural Resources from 1961 to 1965. While in office, he played an pivotal role in the nationalisation of hydroelectric companies, greatly expanding Hydro-Québec, one of the reforms that was part of the Quiet Revolution.[4]

From 1965 to 1966 he served as Minister of Family and Welfare. Lévesque, with friend and Minister of Health Eric Kierans, was heavily involved in negotiations with the Federal government to fund both Quebec and Federal mandates for social programs.

In a surprise, the Liberals lost the 1966 election to the Union Nationale but Lévesque retained his own seat of Laurier. Believing that the Canadian federation was doomed to failure, Lévesque started to openly champion separation from Canada as part of the Liberal platform at the upcoming party conference. Kierans, who had been elected party president, lead the movement against the motion, with future Premier Robert Bourassa attempting to mediate before siding with Kierans. The resolution was handily defeated, and Lévesque walked out with his followers.

Foundation of the Parti Québécois

After leaving the Liberal Party, he founded the Mouvement Souveraineté-Association. In contrast to more militant nationalist movements, such as Pierre Bourgeault's Rassemblement pour l'Indépendance Nationale, the party eschewed direct action and protest and attempted instead to appeal to the broader electorate, whom Lévesque would call "normal people." The main contention in the first party conference was the proposed policy toward Quebec's Anglophone minority, Lévesque faced down heavy opposition to his insistence that English schools and language rights be protected.

The appointment of hardline federalist Pierre Elliott Trudeau as Prime Minister, and the politically damaging riot instigated by the RIN when he appeared at the St. Jean Baptiste Day parade of 1968, led to the sovereignty movement coming together. The MSA would merge with another party in the Quebec sovereignty movement, the Ralliement National of Gilles Grégoire, to create the Parti Québécois in 1968. At Lévesque's insistence, RIN members would be permitted to join but not be accepted as a group.[7]

The PQ would gain 25% of the vote in the 1970 election, running on a platform of declaring independence if government was formed. The PQ only gained 6 seats, and Lévesque continued to run the party from Montreal by communicating with the caucus in Quebec City.

The 1973 election saw a large Liberal victory, and created major tensions within the party, especially after Lévesque was unable to gain a seat. A quarrel with House Leader Robert Burns almost ended Lévesque's leadership shortly thereafter.

First term as Premier

Lévesque and his party won a landslide victory at the 1976 election, with Lévesque finally re-entering the Assembly as the member for Taillon. His party assumed power with 41.1 per cent of the popular vote and 71 seats out of 110, and even managed to unseat Bourassa in his own riding. Lévesque became Premier of Quebec ten days later.

The night of Lévesque's acceptance speech included one of his most famous quotations: "I never thought that I could be so proud to be Québécois."

On February 6, 1977, Lévesque's car fatally struck Edgar Trottier, a homeless man who had been lying on the road. Trottier had in the past repeatedly used the maneuver to secure a hospital bed for the night. Police officers at the scene did not administer the breathalyzer test to Levesque, because they did not suspect that he was impaired.[8] Levesque was later fined $25 for failing to wear his glasses while driving a car on the night in question.[9] The incident gained extra notoriety when it was revealed that the female companion in the vehicle was not his wife, but his longtime secretary, Corinne Côté. Lévesque’s marriage ended in divorce soon thereafter (the couple had already been estranged for some time), and in April 1979, he married Côté.

Lévesque's Act to govern the financing of political parties banned corporate donations and limited individual contributions to political parties to $3,000. This key legislation was meant to prevent wealthy citizens and organizations from having a disproportionate influence on the electoral process. A Referendum Act was passed to allow for a province-wide vote on issues presented in a referendum, giving a "yes" and "no" side equal funding and legal footing.

His government's signature achievement was the Quebec Charter of the French Language (colloquially known as "Bill 101"), whose stated goal was to make French "the normal and everyday language of work, instruction, communication, commerce and business." In its first enactment, it reserved access to English-language public schools to children whose parents had attended English school in Quebec. All other children were required to attend French schools in order to encourage immigrants to integrate themselves into the majority French culture (Lévesque was more moderate on language than some of the PQ, including language minister, Camille Laurin. He would have resigned as leader rather than eliminate English public schools, as party extremists proposed).[10]

Bill 101 also made it illegal for businesses to put up exterior commercial signs in a language other than French (unless the sign also contained a "larger" French translation) at a time when English dominated as a commercial and business language in Quebec (while more than 80% of the population was of French origin).

On May 20, 1980, the PQ held, as promised before the elections, the 1980 Quebec referendum on its sovereignty-association plan. The result of the vote was 40% in favour and 60% opposed (with 86% turnout). Lévesque conceded defeat in the referendum by announcing that, as he had understood the verdict, he had been told "until next time."[11]

Lévesque led the PQ to victory in the 1981 election, increasing the party's majority in the National Assembly and increasing its share of the popular vote from 41 to 49 per cent.

Second Term

A major focus of his second mandate was the patriation of the Canadian constitution. Lévesque was criticized by some in Quebec who said he had been tricked by Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and the English-Canadian provincial premiers. To this day, no Quebec premier of any political side has endorsed the 1982 constitutional amendment.

The PQ government's response to the recession of the early 1980s by cutting the Provincial budget to reduce growing deficits that resulted from the recession angered labour union members, a core part of the constituency of the PQ and the sovereignty movement. Lévesque had argued that the party should not make sovereignty the object of the 1985 election and instead opt for the "Beau risque" strategy of seeking an understanding with the federal government of Mulroney, which angered the strongest supporters of sovereignty within the party. He said the issue in the upcoming election would not be sovereignty. Instead, he expressed hope, "that we can finally find government leaders in Ottawa who will discuss Quebec's demands seriously and work with us for the greater good of Quebecers."[12] His new position weakened his position within the party. Some senior members resigned; there were by-election defeats. Lévesque resigned as leader of the Parti Québécois on June 20, 1985, and as premier of Quebec on October 3, 1985.[13]

Lévesque, a constant smoker,[14] was hosting a dinner party in his Montreal apartment on the evening of November 1, 1987 when he experienced chest pains; he died of a myocardial infarction that night at Montreal General Hospital.[15][16] A brief resurgence of separatist sentiment followed. Over 100,000 viewed his body lying in state in Montreal and Quebec City, over 10,000 went to his funeral in the latter city, and hundreds wept daily at his grave for months.[17]

Lévesque was a recipient of the title Grand Officer of the French Legion of Honour. He was posthumously made a Grand Officer of the National Order of Quebec in 2008.

Legacy

Despite a perceived weakening of his sovereigntist resolve in the last years of his government, he reaffirmed his belief to friends and, notably, to a crowd of Université Laval students months before his death, of the necessity of independence.

His state funeral and funeral procession was reportedly attended by 100,000 Québécois. During the carrying out of his coffin from the church, the crowd spontaneously began to applaud and sing Quebec's unofficial national anthem "Gens du pays", replacing the first verse with Mon cher René (My dear René), as is the custom when this song is adapted to celebrate someone's birthday. Two major boulevards now bear his name, one in Montreal and one in Quebec City. In Montreal, Édifice Hydro-Québec and Maison Radio-Canada are both located on René Lévesque Boulevard, fittingly as Lévesque once worked for Hydro-Québec and the CBC, respectively. On June 22, 2010, Hydro-Québec and the government of Quebec commemorated Lévesque's role in Quebec's Quiet Revolution and his tenure as premier by renaming the 1244-megawatt Manic-3 generating station in his honour.[18]

On June 3, 1999, a monument in his honour was unveiled on boulevard René-Lévesque outside the Parliament Building in Quebec City. The statue is popular with tourists, who snuggle up to it, to have their pictures taken "avec René" (with René), despite repeated attempts by officials to keep people from touching the monument or getting too close to it. The statue had been the source of an improvised, comical and affectionately touching tribute to Lévesque. The fingers of his extended right hand are slightly parted, just enough so that tourists and the faithful could insert a cigarette, giving the statue an unusually realistic appearance.

This practice is less often seen now, however, as the statue was moved to New Carlisle and replaced by a similar, but bigger one. This change resulted from considerable controversy. Some believed that the life-sized statue was not appropriate for conveying his importance in the history of Quebec. Others noted that a trademark of Lévesque was his relatively small stature.

Lévesque today remains an important figure of the Quebec nationalist movement, and is considered sovereigntism's spiritual father. After his death, even people in disagreement with some of those convictions now generally recognise his importance to the history of Quebec. Many in Quebec regard him as the father of the modern Quebec nation. According to a study made in 2006 by Le Journal de Montréal and Léger Marketing, René Lévesque was considered by far, according to Québécois, the best premier to run the province over the last 50 years.[19]

Of the things he left as his legacy, some of the most memorable and still robust are completing the nationalization of hydroelectricity through Hydro-Québec, the Quebec Charter of the French Language, the political party financing law, and the Parti Québécois itself. His government was the first in Canada to prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation in the province's Charte des droits de la personne in 1977.[20] He also continued the work of the Lesage government in improving social services, in which social needs were taken care of by the state, instead of the Catholic Church (as in the Duplessis era) or the individual. Lévesque is still regarded by many as a symbol of democracy and tolerance.

Lévesque was notably portrayed in the television series René Lévesque. In 2006, an additional television miniseries, René Lévesque, was aired on the CBC. He was also portrayed in an episode of Kevin Spencer, a Canadian cartoon show. In it, his ghost attempted a camaraderie with Kevin because of their similarities in political beliefs, as well as the fact that the title character, like René's ghost, claims to smoke "five packs a day".

A song by Les Cowboys Fringants named Lettre à Lévesque on the album La Grand-Messe was dedicated to him. They have also mentioned the street bearing his name in the song called La Manifestation.

He was the co-subject along with Pierre Trudeau in the Donald Brittain-directed documentary mini-series The Champions.

Personality

Lévesque was a man capable of great tact and charm, but who could also be abrupt and choleric when defending beliefs, ideals, or morals essential to him, or when lack of respect was perceived, for example, when he was famously snubbed by François Mitterrand at their first meeting. He was also a proud Gaspésien (from the Gaspé peninsula), and had hints of the local accent.

Considered a major defender of Québécois, Lévesque was, before the 1960s, more interested in international affairs than Quebec matters. The popular image of Lévesque was his ever-present cigarette and his small physical stature, as well as his unique comb over that earned him the nickname of Ti-Poil, literally, "Lil' Hair", but more accurately translated as "Baldy". Lévesque was a passionate and emotional public speaker. Those close to Lévesque have described him as having difficulty expressing his emotions in private, saying that he was more comfortable in front of a crowd of thousands than with one person.

While many Quebec intellectuals are inspired by French philosophy and high culture, Lévesque favoured the United States of America. While in London during the Second World War, his admiration for Britons grew when he witnessed their courage in the face of the German bombardments. He was a faithful reader of the New York Times, and took his vacations in New England every year. He also stated that, if there had to be one role model for him, it would be U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Lévesque was disappointed with the cold response by the American economic elite to his first speech in New York City as Premier of Quebec, in which he compared Quebec's march towards sovereignty to the American Revolution. His first speech in France was, however, more successful, leading him to a better appreciation of the French intelligentsia and of French culture.

Works

- My Québec, 1979, Methuen, 191 pages, ISBN 0-458-93980-3

- Quotations from René Lévesque, 1977, Éditions Héritage, 105 pages ISBN 0-7773-3942-0

- An Option for Quebec, 1968, McClelland and Stewart, 128 pages

- "For an Independent Quebec", in Foreign Affairs, July, 1976)

- Option Québec (1968)

- La passion du Québec (1978)

- Oui (1980)

- Attendez que je me rappelle (1986) (although the title means 'Wait for me to remember'; the title of the English-language version was Memoirs)[21]

See also

- List of Gaspésiens

- List of premiers of Quebec

- List of Quebec general elections

- Politician nicknaming in Quebec

- Politics of Quebec

- Separatism

References

- ↑ "The St-Gelais Families of North America". Familyorigins.com. Retrieved 2012-01-05.

- ↑ "Trudeau pays his last respects to Rene Levesque He joins thousands to bid farewell to former premier". November 4, 1987.

- ↑ Rene Lévesque dies from massive heart attack CBC.ca Retrieved 2016-08-12

- 1 2 3 4 5 Foot, Richard. "René Lévesque". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2016-03-06.

- ↑ "René Lévesque - National Assembly of Québec". www.assnat.qc.ca. Retrieved 2016-03-06.

- ↑ "Rene Levesque | premier of Quebec". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2016-03-06.

- ↑ "CBC Archives". www.cbc.ca. Retrieved 2016-03-06.

- ↑ Stars and Stripes (Washington, D.C.), 23 February 1977, p.31.

- ↑ The Brandon Sun (Manitoba), 15 July 1977, p.3.

- ↑ Gazette, The (2007-11-04). "Legacy of a legend". Canada.com. Retrieved 2012-01-05.

- ↑ "Zone Nouvelles - Radio-Canada.ca". ici.radio-canada.ca. Retrieved 2016-03-06.

- ↑ Peter M. Leslie (1985). Canada, the State of the Federation, 1985. IIGR, Queen's University. pp. 48–49. ISBN 9780889114425.

- ↑ Leslie (1985). Canada, the State of the Federation, 1985. p. 49. ISBN 9780889114425.

- ↑ Graham Fraser, Ivon Owen. René Lévesque & the Parti Québécois in Power, p.13. McGill-Queen's Press, 2001, ISBN 0-7735-2323-5

- ↑ Paulin, Marguerite. René Lévesque, p.123. XYZ Publishing, 2004, ISBN 1-894852-13-3

- ↑ Godin, Pierre (2005). René Lévesque, l'homme brisé. 4. Montréal: Boréal. p. 528. ISBN 2-7646-0424-6.

- ↑ Conway, John Frederick. Debts to Pay, pp.128–29. James Lorimer & Company, 2004, ISBN 1-55028-814-8

- ↑ Presse canadienne (2010-06-22). "Deux centrales porteront les noms de Jean Lesage et René Lévesque". La Presse (in French). Montréal. Retrieved 2010-06-22.

- ↑ "René Lévesque a été le meilleur premier ministre". Lcn.canoe.com. 2009-04-23. Retrieved 2012-01-05.

- ↑ "Library of Parliament Research Publications". Parl.gc.ca. Retrieved 2012-01-05.

- ↑ Lévesque book skirts many painful memories. Ottawa Citizen, 16 October 1986. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

Further reading

- Desbarats, Peter (1976). Rene: a Canadian in search of a country, McClelland and Stewart, 223 pages ISBN 0-7710-2691-9

- Dupont, Pierre (1977). How Levesque Won, Lorimer, 136 pages ISBN 0-88862-130-2 (translated by Sheila Fischman)

- Fennario, David (2003). The Death of René Lévesque, Talonbooks, March 10, 72 pages ISBN 0-88922-480-3

- Fournier, Claude (1995). René Lévesque: Portrait of a Man Alone, McClelland & Stewart, April 15, 272 pages ISBN 0-7710-3216-1

- Fraser, Graham (2002). PQ: René Lévesque and the Parti Québécois in Power, Montreal, McGill-Queen's University Press; 2nd edition, 434 pages ISBN 0-7735-2310-3

- Paulin, Marguerite (2004). René Lévesque: Charismatic Leader, XYZ Publishing, 176 pages ISBN 1-894852-13-3 (translated by Jonathan Kaplansky)

- Provencher, Jean and Ellis, David (1977). René Lévesque: Portrait of a Québécois, Paperjacks, ISBN 0-7701-0020-1

- Vacante, Jeffery. "The Posthumous Lives of René Lévesque," Journal of Canadian Studies/Revue d'études canadiennes (2011) 45#2 pp 5–30 online, historiography

- "René Lévesque's Separatist Fight", in the CBC Archives Web site

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to René Lévesque. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: René Lévesque |

| National Assembly of Quebec | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Arsène Gagné (Union Nationale) |

MNA, District of Laurier 1960–1970 |

Succeeded by André Marchand (Liberal) |

| Preceded by Guy Leduc (Liberal) |

MNA, District of Taillon 1976–1985 |

Succeeded by Claude Filion (PQ) |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Robert Bourassa (Liberal) |

Premier of Quebec 1976–1985 |

Succeeded by Pierre-Marc Johnson (PQ) |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by none |

Leader of the Parti Québécois 1968–1985 |

Succeeded by Pierre-Marc Johnson |