Rhyme scheme

A rhyme scheme is the pattern of rhymes at the end of each line of a poem or song. It is usually referred to by using letters to indicate which lines rhyme; lines designated with the same letter all rhyme with each other.

|

|

Function in writing

Rhyme scheme is as integral to the structure of a text as rhythm, meter and length of phrase. Yet the way this happens seems more ambiguous than the way rhythm shapes a text, for example. Even some seasoned writers have difficulty understanding precisely how the organization of rhyme contributes to the architecture of a poem or a song.

Basically, like the other elements of writing, rhyme scheme is used to manage flow, create and relieve tension & balance, and to highlight important ideas.

Writers may choose rhyme schemes in order to:

- Control the speed & flow of the structure

- Take control of the audience's expectations

- Communicate an idea in the most effective way

Instead of choosing rhyme schemes haphazardly, writers can deliberately design the structure of rhyme to support their ideas.

Rhymes accelerate a text. The more times a line rhymes, the smoother the flow, and the faster it goes.

Take the most basic "AAAA" rhyme scheme for example:

There was a cat,

His name was Pat,

Outside, he sat,

And boy was he fat!

When each line ends the same way, it is smooth, and can be read quickly. Because every line rhymes, the reader doesn't slow down anywhere when they read it. If the last line was supposed to be the punchline of the poem, so to speak, then it didn't really work, because the AAAA pattern kept them reading too fast to stop at the end.

A basic distinction is between rhyme schemes that apply to a single stanza, and those that continue their pattern throughout an entire poem (see chain rhyme). There are also more elaborate related forms, like the sestina – which requires repetition of exact words in a complex pattern.

In English, highly repetitive rhyme schemes are unusual. English has more vowel sounds than Italian, for example, meaning that such a scheme would be far more restrictive for an English writer than an Italian one – there are fewer suitable words to match a given pattern. Even such schemes as the terza rima ("aba bcb cdc ded..."), used by Dante Alighieri in The Divine Comedy, have been considered too difficult for English.

Examples

- Alternate rhyme: ABAB CDCD EFEF GHGH...

- Ballade: Three stanzas of "ABABBCBC" followed by "BCBC".

- Boy Named Sue: A,A,B,C,C,(B, or infrequently D).

- Chant royal: Five stanzas of "ababccddedE" followed by either "ddedE" or "ccddedE". (The capital letters indicate a line repeated verbatim.)

- Cinquain: "A,B,A,B,B"

- Clerihew: "A,A,B,B"

- Couplet: "A,A", but usually occurs as "A,A, B,B C,C D,D ..."

- McCarron Couplet: "AABBABCCDDCDEEFFEF" a contemporary take on a classic rhyming pattern, introduced by the academic James McCarron.

- Creative Verse: A poem with the rhyme scheme of "ABCD ACDC ACDC", followed with as many repetitions of ACDC as desired.

- Enclosed rhyme (or enclosing rhyme): "ABBA"

- "Fire and Ice" stanza: "ABAABCBCB" as used in Robert Frost's poem "Fire and Ice"

- Keatsian Ode: "ABABCDECDE" used in Keat's Ode on Indolence, Ode on a Grecian Urn, and Ode to a Nightingale.

- Limerick: "AABBA"

- Monorhyme: "A,A,A,A,A...", an identical rhyme on every line, common in Latin and Arabic

- Ottava rima: "A,B,A,B,A,B,C,C"

- The Raven stanza: "ABCBBB", or "AA,B,CC,CB,B,B" when accounting for internal rhyme, as used by Edgar Allan Poe in "The Raven"

- Rhyme royal: "ABABBCC"

- Rondeau: "ABaAabAB"

- Rondelet: "AbAabbA"

- Rubaiyat: "AABA"

- Scottish stanza: "AAABAB", as used by Robert Burns in works such as "To a Mouse"

- Simple 4-line: "ABCB"

- Sonnet ABAB CDCD EFEF GG

- Petrarchan sonnet: "ABBA ABBA CDE CDE" or "ABBA ABBA CDC DCD"

- Shakespearean sonnet: "ABAB CDCD EFEF GG"

- Spenserian sonnet: "ABAB BCBC CDCD EE"

- Onegin stanzas: "aBaBccDDeFFeGG" with the lowercase letters representing feminine rhymes and the uppercase representing masculine rhymes, written in iambic tetrameter

- Sestina: ABCDEF FAEBDC CFDABE ECBFAD DEACFB BDFECA, the seventh stanza is a tercet where line 1 has A in it but ends with D, line 2 has B in it but ends with E, line 3 has C in it but ends with F

- Spenserian stanza: "ABABBCBCCDCDEE"

- Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening form: "AABA BBCB CCDC DDDD" a modified Ruba'i stanza used by Robert Frost for the eponymous poem.

- Tanaga: traditional Tagalog tanaga is "AAAA"

- Terza rima: "ABA BCB CDC ...", ending on "YZY Z", "YZY ZZ", or "YZY ZYZ".

- Triplet: "AAA", often repeating like the couplet.

- The Road Not Taken stanza: "ABAAB" as used in Robert Frost's The Road Not Taken, and in Glæde over Danmark by Poul Martin Møller (English translation here).

- Villanelle: A1bA2 abA1 abA2 abA1 abA2 abA1A2, where A1 and A2 are lines repeated exactly which rhyme with the a lines.

Films and TV

In Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory, all the "A" rhymes go during a ride in the Wonkatania said by the following:

- There's no earthly way of knowing

- which direction we are going.

- There is no knowing where we're rowing

- or which way the river's flowing.

In hip-hop music

Hip-hop music and rapping's rhyme schemes include traditional schemes such as couplets, as well as forms specific to the genre,[1] which are broken down extensively in the books How to Rap and Book of Rhymes. Rhyme schemes used in hip-hop music include –

Couplets are the most common type of rhyme scheme in old school rap[7] and are still regularly used,[2] though complex rhyme schemes have progressively become more frequent.[8][9] Rather than relying on end rhymes, rap's rhyme schemes can have rhymes placed anywhere in the bars of music to create a structure.[10] There can also be numerous rhythmic elements which all work together in the same scheme[11] – this is called internal rhyme in traditional poetry,[12] though as rap's rhymes schemes can be anywhere in the bar, they could all be internal, so the term is not always used.[11] Rap verses can also employ 'extra rhymes', which do not structure the verse like the main rhyme schemes, but which add to the overall sound of the verse.[13]

Number of rhyme schemes

The number of different possible rhyme schemes for an n-line poem is given by the Bell numbers,[14] which for n = 1, 2, 3, ... are

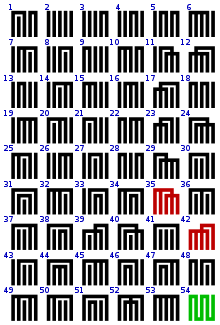

For instance, there are five different rhyme schemes for a three-line poem: AAA, AAB, ABA, ABB, and ABC. Historically, the first exhaustive listing of rhyme schemes appears to be in the Tale of Genji, an 11th-century Japanese novel whose chapters are headed by diagrams representing the 52 rhyme schemes of a five-line poem.[14] The number of rhyme schemes in which all lines rhyme with at least one other line is given by the numbers

For instance the four such rhyme schemes for a four-line poem are AABB, ABAB, ABBA, and AAAA. Both sequences of numbers may be found on either side of an augmented version of the Bell triangle.

References

- ↑ Edwards, Paul, 2009, How to Rap: The Art & Science of the Hip-Hop MC, Chicago Review Press, p. 95-110.

- 1 2 Edwards, Paul, 2009, How to Rap: The Art & Science of the Hip-Hop MC, Chicago Review Press, p. 99.

- ↑ Edwards, Paul, 2009, How to Rap: The Art & Science of the Hip-Hop MC, Chicago Review Press, p. 100.

- ↑ Edwards, Paul, 2009, How to Rap: The Art & Science of the Hip-Hop MC, Chicago Review Press, p. 101.

- ↑ Edwards, Paul, 2009, How to Rap: The Art & Science of the Hip-Hop MC, Chicago Review Press, p. 101-102.

- ↑ Edwards, Paul, 2009, How to Rap: The Art & Science of the Hip-Hop MC, Chicago Review Press, p. 102-103.

- ↑ Bradley, Adam, 2009, Book of Rhymes: The Poetics of Hip-Hop, Basic Civitas Books, p. 50.

- ↑ Edwards, Paul, 2009, How to Rap Like A Star: The Art & Science of the Hip-Hop MC, Chicago Review Press, p. 97.

- ↑ Bradley, Adam, 2009, Book of Rhymes: The Poetics of Hip-Hop, Basic Civitas Books, p. 73.

- ↑ Edwards, Paul, 2009, How to Rap: The Art & Science of the Hip-Hop MC, Chicago Review Press, p. 107.

- 1 2 Edwards, Paul, 2009, How to Rap: The Art & Science of the Hip-Hop MC, Chicago Review Press, p. 104.

- ↑ Bradley, Adam, 2009, Book of Rhymes: The Poetics of Hip-Hop, Basic Civitas Books, p. 74.

- ↑ Edwards, Paul, 2009, How to Rap: The Art & Science of the Hip-Hop MC, Chicago Review Press, p. 103.

- 1 2 Gardner, Martin (1978), "The Bells: versatile numbers that can count partitions of a set, primes and even rhymes", Scientific American, 238: 24–30, doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0578-24. Reprinted with an addendum as "The Tinkly Temple Bells", Chapter 2 of Fractal Music, Hypercards, and more ... Mathematical Recreations from Scientific American, W. H. Freeman, 1992, pp. 24–38.

External links

- Lingua::Rhyme::FindScheme — Perl module to find the rhyme scheme of a given text.

-

Rhyme schemes by set partition

Rhyme schemes by set partition