Riccoldo da Monte di Croce

Riccoldo da Monte di Croce or Ricoldo of Monte Croce (Pennini, that is "son of Pennino"; Latin: Ricoldus de Monte Crucis), c. 1243 – 1320, was an Italian Dominican monk, travel writer, missionary, and Christian apologist.

Life

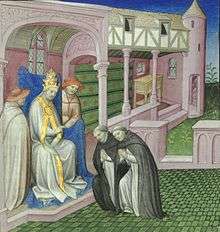

Riccoldo was born in Florence, and his family name originated from a small castle just above Pontassieve. After studying in various major European schools, he became a Dominican in 1267, entering the house of Santa Maria Novella. He was a professor in several convents of Tuscany, including St Catherine in Pisa (1272–99). With a papal commission to preach he departed for Acre (Antiochia Ptolemais) in 1286 or 1287 and made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land (1288) and then travelled for many years as a missionary in western Asia. He arrived in Mossul in 1289, equipped with a Papal bull. He failed to convince the Nestorian Christian mayor of the city to convert to Catholicism.[1] He was a missionary to the court of the Mongol Il-Khan ruler Arghun, of whom he wrote that he was "a man given to the worst of villainy, but for all that a friend of the Christians".[2]

Moving to Baghdad, Riccoldo entered in conflict with the local Nestorian Christians, preaching against them in their own cathedral. He was allowed nonetheless by Mongol authorities to build his own church, with the interdiction to preach in public. Riccoldo brought the matter to the Nestorian patriarch Mar Yaballaha, who agreed with him that the doctrine of Nestorius, namely the duality of Christ (thus achieving a theoretical fusion of the Latin Church and the Church of the East) was heretical. Mar Yaballaha was however disavowed by his own followers.[1]

He returned to Florence before 1302, and was chosen to high offices in his order. He died in Florence on 31 October 1320.

Works

Travels and Liber Peregrinacionis

His Liber Peregrinacionis or Itinerarius (written about 1288–91) was intended as a guide-book for missionaries, and is a description of the Oriental countries he visited.

In 1288 or 1289 he began to keep a record of his experiences in the Levant; this record he probably reduced to final book form in Baghdad. Entering Syria at Acre, he crossed Galilee to the Sea of Tiberias; thence returning to Acre he seems to have travelled down the coast to Jaffa, and so up to Jerusalem. After visiting the Jordan River and the Dead Sea he left Palestine by the coast road, retracing his steps to Acre and passing on by Tripoli and Tortosa into Cilicia. From the Cilician port of Lajazzo (now Yumurtalik in Turkey) he started on the great high road to Tabriz in north Persia. Crossing the Taurus he travelled on by Sivas of Cappadocia to Erzerum, the neighborhood of Ararat and Tabriz. In and near Tabriz he preached for several months, after which he proceeded to Baghdad via Mosul and Tikrit. In Baghdad he stayed several years.

As a traveller and observer his merits are conspicuous. His account of the Tatars and his sketch of Islamic religion and manners are especially noteworthy. In spite of strong prejudice, he shows remarkable breadth of view and appreciation of merit in systems the most hostile to his own.

On the Fall of Acre

The Epistolæ de Perditione Acconis are five letters in the form of lamentations over the fall of Acre (written about 1292, published in Paris, 1884).

| “ | And so it came to pass that I was in Baghdad, “among the captives by the river of Chebar” [Ezek. 1:1], the Tigris. This garden of delights in which I found myself enthralled me, for it was like a paradise in its abundance of trees, its fertility, its many fruits. This garden was watered by the rivers of Paradise, and the inhabitants built gilt houses all around it. Yet I was saddened by the massacre and capture of the Christian people. I wept over the loss of Acre, seeing the Saracens joyous and prospering, the Christians squalid and consternated: little children, young girls, old people, whimpering, threatened to be led as captives and slaves into the remotest countries of the East, among barbarous nations.

Suddenly, in this sadness, swept up into an unaccustomed astonishment, I began, stupefied, to ponder God's judgment concerning the government of the world, especially concerning the Saracens and the Christians. What could be the cause of such massacre and such degradation of the Christian people? Of so much worldly prosperity for the perfidious Saracen people? Since I could not simply be amazed, nor could I find a solution to this problem, I decided to write to God and his celestial court, to express the cause of my astonishment, to open my desire through prayer, so that God might confirm me in the truth and sincerity of the Faith, that he quickly put an end to the law, or rather the perfidy, of the Saracens, and more than anything else that he liberate the Christian captives from the hands of the enemies.

|

” |

Apologetic writings against Islam and Judaism

During his stay in Baghdad, Riccoldo studied the Qur'an and other works of Islamic theology, for controversial purposes, arguing with Nestorian Christians, and writing. In 1300–1301 Riccoldo again appeared in Florence. About 1300 in Florence he wrote Contra legem Sarracenorum and Ad nationes orientales.

Riccoldo's best known work of this kind was the Contra Legem Sarracenorum, written in Baghdad, which has in previous centuries been very popular among Christians as a polemical source against Islam, and has been often edited (first published in Seville, 1500, under the title Confutatio Alcorani, "Confutation of the Koran"). This work was translated into German (Verlegung des Alcoran) by Martin Luther in 1542. There are translations into English by Thomas C. Pfotenhauer (Islam in the Crucible: Can it pass the test?, Lutheran News, Inc., 2002), and Londini Ensis, under the title, "Refutation of the Koran" (Createspace 2010).

Much of this work's contents derive from those sections of the Liber Peregrinacionis devoted to Muslim beliefs and related topics. One of Riccoldo's major sources, extensively quoted in his own work, is the anonymous Liber denudationis siue ostensionis aut patefaciens.[3] Despite Riccoldo's hostility towards Islam, his work shows specific knowledge of the Qur'an and overcomes one important prejudicial error common to other Medieval criticisms of Islam: the view of Muhammad as introducer of a Christological heresy.[4]

The Christianæ Fidei Confessio facta Sarracenis (printed in Basle, 1543) is attributed to Riccoldo, and was probably written about the same time as the above-mentioned works. Other works are: Contra errores Judæorum (Against the Errors of the Jews); Libellus contra nationes orientales (MSS. at Florence and Paris); Contra Sarracenos et Alcoranum (MS. at Paris); De variis religionibus (MS. at Turin; compare the final chapter of the Liber Peregrinacionis, "De variis religionibus terre sancte"). Very probably the last three works were written after his return to Europe. Riccoldo is also known to have written two theological works—a defence of the doctrines of Thomas Aquinas (in collaboration with John of Pistoia, about 1285) and a commentary on the Libri sententiarum (before 1288). Riccoldo began a translation of the Quran about 1290, but it is not known whether this work was completed.

Notes

References

- George-Tvrtkovic, Rita. A Christian Pilgrim in Medieval Iraq: Riccoldo da Montecroce's Encounter with Islam. Turnhout, Brepols Press (2012).

- Burman, Thomas E. (1994). Religious polemic and the intellectual history of the Mozarabs, c.1050–1200, Leiden: Brill.

- Jackson, Peter, The Mongols and the West, Pearson Education Ltd, ISBN 0-582-36896-0

- Roux, Jean-Paul, Histoire de l'Empire Mongol, Fayard, ISBN 2-213-03164-9

- Tolan, John V. (2002). Saracens: Islam in the medieval European imagination, New York: Columbia University Press.

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Ricaldo da Monte di Croce". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Ricaldo da Monte di Croce". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton. -

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

- Riccoldi Florentini Libelli ad nationes orientales (web edition)

- Epistolae V commentatoriae de perditione Acconis, ed. Reinhold Röhricht, in Archives de l'Orient latin, vol. 2 (1884), pp. 258–296 = Google PDF pp. 765–792

- Liber Peregrinacionis, ed. J.C.M. Laurent, Leipzig, 1864 (in Peregrinatores Medii Aevi Quattuor, pp. 101ff. = Google PDF pp. 116 ff.)

- Confutatio alcorani (Bartolomeus Picernus' retranslation into Latin from the Greek of Demetrios Kydones), Basel, 1507, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek copy (OCLC 165364264)

- Ed Emery, "Riccoldo of Monte Croce", Research Notes on Dante Alighieri

- Emilio Panella, Riccoldo di Pennino da Monte di Croce

- Klaus Peter Todt (1994). "Riccoldo da Monte Croce". In Bautz, Traugott. Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL) (in German). 8. Herzberg: Bautz. cols. 191–194. ISBN 3-88309-053-0.