Richard Avedon

| Richard Avedon | |

|---|---|

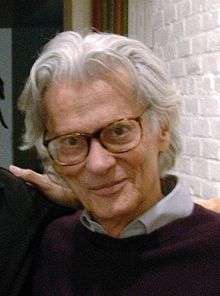

Richard Avedon, 2004 | |

| Born |

May 15, 1923 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died |

October 1, 2004 (aged 81) San Antonio, Texas, U.S. |

| Alma mater | The New School for Social Research |

| Known for | Photography |

| Spouse(s) |

Dorcas Marie "Doe" (Nowell) Avedon (m. 1944; div. 1949) Evelyn Franklin (m. 1951) |

Richard Avedon (May 15, 1923 – October 1, 2004) was an American fashion and portrait photographer. An obituary published in The New York Times said that "his fashion and portrait photographs helped define America's image of style, beauty and culture for the last half-century".[1]

Early life and education

Avedon was born in New York City, to a Jewish family. His father, Jacob Israel Avedon, was a Russian-born immigrant who advanced from menial work to starting his own successful retail dress business on Fifth Avenue, called Avedon’s Fifth Avenue.[2][3] His mother, Anna, from a family that owned a dress-manufacturing business,[1] encouraged Richard's love of fashion and art. Avedon’s interest in photography emerged when, at age 12, he joined a Young Men’s Hebrew Association (YMHA) Camera Club. He would use his family’s Kodak Box Brownie not only to feed his curiosity about the world, but also to retreat from his personal life. His father was a critical and remote disciplinarian who insisted that physical strength, education and money prepared one for life.[2] The photographer's first muse was his younger sister, Louise. During her teen years she struggled through psychiatric treatment. And, eventually, becoming increasingly withdrawn from reality, was diagnosed with schizophrenia.[4] These early influences of fashion and family would shape Avedon's life and career, often expressed in his desire to capture tragic beauty in photos.

Avedon attended DeWitt Clinton High School in Bedford Park, Bronx, where he worked on the school paper, The Magpie, with James Baldwin from 1937 until 1940.[5] New York City High Schools.[3] After graduating from DeWitt that year, he enrolled at Columbia University to study philosophy and poetry but dropped out after one year. He then started as a photographer for the Merchant Marines, taking ID shots of the crewmen with the Rolleiflex camera his father had given him as a gift. From 1944 to 1950, Avedon studied photography with Alexey Brodovitch at his Design Laboratory at The New School for Social Research.[1]

Photography career

In 1944, Avedon began working as an advertising photographer for a department store, but was quickly endorsed by Alexey Brodovitch, who was art director for the fashion magazine Harper's Bazaar. Lillian Bassman also promoted Avedon's career at Harper's. In 1945 his photographs began appearing in Junior Bazaar and, a year later, in Harper's Bazaar.[1]

In 1946, Avedon had set up his own studio and began providing images for magazines including Vogue and Life. He soon became the chief photographer for Harper's Bazaar. From 1950 he also contributed photographs to Life, Look and Graphis and in 1952 became Staff Editor and photographer for Theatre Arts Magazine. Avedon did not conform to the standard technique of taking studio fashion photographs, where models stood emotionless and seemingly indifferent to the camera. Instead, Avedon showed models full of emotion, smiling, laughing, and, many times, in action in outdoor settings which was revolutionary at the time. However, towards the end of the 1950s he became dissatisfied with daylight photography and open air locations and so turned to studio photography, using strobe lighting.[6]

When Diana Vreeland left Harper's Bazaar for Vogue in 1962, Avedon joined her as a staff photographer.[7] He proceeded to become the lead photographer at Vogue and photographed most of the covers from 1973 until Anna Wintour became editor in chief in late 1988. Notable among his fashion advertisement series are the recurring assignments for Gianni Versace, beginning with the spring/summer campaign 1980. He also photographed the Calvin Klein Jeans campaign featuring a fifteen-year-old Brooke Shields, as well as directing her in the accompanying television commercials. Avedon first worked with Shields in 1974 for a Colgate toothpaste ad. He shot her for Versace, 12 American Vogue covers and Revlon's Most Unforgettable Women campaign. In the February 9, 1981, issue of Newsweek, Avedon said that "Brooke is a lightning rod. She focuses the inarticulate rage people feel about the decline in contemporary morality and destruction of innocence in the world." On working with Avedon, Shields told Interview magazine in May 1992 "When Dick walks into the room, a lot of people are intimidated. But when he works, he's so acutely creative, so sensitive. And he doesn't like it if anyone else is around or speaking. There is a mutual vulnerability, and a moment of fusion when he clicks the shutter. You either get it or you don't".

In addition to his continuing fashion work, by the 1960s Avedon was making studio portraits of civil rights workers, politicians and cultural dissidents of various stripes in an America fissured by discord and violence.[8] He branched out into photographing patients of mental hospitals, the Civil Rights Movement in 1963, protesters of the Vietnam War, and later the fall of the Berlin Wall.

A personal book called “Nothing Personal,” with a text by his high school classmate James Baldwin appeared in 1964.[8] During this period, Avedon also created two well known sets of portraits of The Beatles. The first, taken in mid to late 1967, became one of the first major rock poster series, and consisted of five psychedelic portraits of the group — four heavily solarized individual color portraits and a black-and-white group portrait taken with a Rolleiflex camera and a normal Planar lens. The next year he photographed the much more restrained portraits that were included with The Beatles LP in 1968. Among the many other rock bands photographed by Avedon, in 1973 he shot Electric Light Orchestra with all the members exposing their bellybuttons for recording, On the Third Day.

Avedon was always interested in how portraiture captures the personality and soul of its subject. As his reputation as a photographer became widely known, he photographed many noted people in his studio with a large-format 8×10 view camera. His subjects include Buster Keaton, Marian Anderson, Marilyn Monroe, Ezra Pound, Isak Dinesen, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Andy Warhol, and the Chicago Seven.[9] His portraits are distinguished by their minimalist style, where the person is looking squarely at the camera, posed in front of a sheer white background. By eliminating the use of soft lights and props, Avedon was able to focus on the inner worlds of his subjects evoking emotions and reactions.[4] He would at times evoke reactions from his portrait subjects by guiding them into uncomfortable areas of discussion or asking them psychologically probing questions. Through these means he would produce images revealing aspects of his subject's character and personality that were not typically captured by others.[10]

Avedon's mural groupings featured emblematic figures: Andy Warhol with the players and stars of The Factory; The Chicago Seven, political radicals charged with conspiracy to incite riot at the 1968 Democratic National Convention; the Beat poet Allen Ginsberg and his extended family; and the Mission Council, a group of military and government officials who governed the United States' participation in the Vietnam War.[11]

In 1982 Avedon produced a playfully inventive series of advertisements for fashion label Christian Dior, based on the idea of film stills. Featuring director Andre Gregory, photographer Vincent Vallarino and model/actress Kelly Le Brock, the color photographs purported to show the wild antics of a fictional "Dior family" living ménage à trois while wearing elegant fashions.[12]

Avedon became the first staff photographer for The New Yorker in 1992,[13] where his post-apocalyptic, wild fashion fable “In Memory of the Late Mr. and Mrs. Comfort,” featuring model Nadja Auermann and a skeleton, was published in 1995. Other pictures for the magazine, ranging from the first publication, in 1994, of previously unpublished photos of Marilyn Monroe to a resonant rendering of Christopher Reeve in his wheelchair and nude photographs of Charlize Theron in 2004, were topics of wide discussion. Some of his less controversial New Yorker portraits include those of Saul Bellow, Hillary Clinton, Toni Morrison, Derek Walcott, John Kerry, and Stephen Sondheim.[1] In his later years, he continued to contribute to Egoïste, where his photographs appeared from 1984 through 2000. In 1999, Avedon shot the cover photos for Japanese-American singer Hikaru Utada's Addicted to You.

Photographer Annie Leibovitz names Avedon as a major influence, describing his style as ‘personal reportage’, developing close rapport with one's subjects.

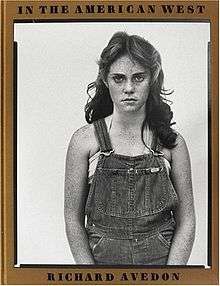

In the American West

One of the things Avedon is distinguished by as a photographer is his large prints, sometimes measuring over three feet in height. His large-format portrait work of drifters, miners, cowboys and others from the western United States became a best-selling book and traveling exhibit entitled In the American West, and is regarded as an important hallmark in 20th century portrait photography, and by some as Avedon's magnum opus.

Serious heart inflammations hindered Avedon’s health in 1974.[10] The troubling time inspired him to create a compelling collection from a new perspective. In 1979, he was commissioned by Mitchell A. Wilder (1913–1979), the director of the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, to complete the “Western Project.”[14] Wilder envisioned the project to portray Avedon’s take on the American West. It became a turning point in Avedon’s career when he focused on everyday working class subjects such as miners soiled in their work clothes, housewives, farmers and drifters on larger-than-life prints, instead of the more traditional options of focusing upon noted public figures or the openness and grandeur of the West.[15] The project lasted five years concluding with an exhibition and a catalogue. It allowed Avedon and his crew to photograph 762 people and expose approximately 17,000 sheets of 8×10 Kodak Tri-X Pan film.[15][16] The collection identified a story within his subjects of their innermost self, a connection Avedon admits would not have happened if his new sense of mortality through severe heart conditions and aging hadn’t occurred.[10] Avedon visited and traveled through state fair rodeos, carnivals, coal mines, oil fields, slaughter houses and prisons to find subjects.[15] In 1994, Avedon revisited his subjects who would later speak about In the American West aftermath and its direct effects. Billy Mudd, a trucker, went long periods of time on his own away from his family. He was a depressed, disconnected and lonely man before Avedon offered him the chance to be photographed. When he saw his portrait for the first time, Mudd saw that Avedon was able to reveal something about Mudd that allowed him to recognize the need for change in his life. The portrait transformed Mudd, and led him to quit his job and return to his family.

Helen Whitney’s 1996 American Masters documentary episode, Avedon: Darkness and Light, depicts an aging Avedon identifying In the American West as his best body of work.[10] The project was embedded with Avedon’s goal to discover new dimensions within himself, from a Jewish photographer from the East who celebrated the lives of noted public figures, to an aging man at one of the last chapters of his life, to discovering the inner-worlds, and untold stories of his Western rural subjects.

During the production period Avedon encountered problems with size availability for quality printing paper. While he experimented with platinum printing he eventually settled on Portriga Rapid, a double-weight, fiber-based gelatin silver paper manufactured by Agfa-Gevaert. Each print required meticulous work, with an average of thirty to forty manipulations. Two exhibition sets of In the American West were printed as artist proofs, one set to remain at the Carter after the exhibition there, and the other, property of the artist, to travel to the subsequent six venues. Overall, the printing took nine months, consuming about 68,000 square feet of paper.[15]

While In the American West is one of the Avedon’s most notable works, it has often been criticized for falsifying the West through voyeuristic themes and for exploiting his subjects. Critics question why a photographer from the East who traditionally focuses on models or public figures would go out West to capture the working class members who represent hardship and suffering. They argue that Avedon's intentions are to influence and evoke condescending emotions from the viewer such as pity.[16]

Exhibitions

Avedon had numerous museum exhibitions around the world. His first major retrospective was at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts in 1970.[17] The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, presented two solo exhibitions during his lifetime, in 1978 and 2002. In 1980 another retrospective was organized by the University Art Museum in Berkeley. Major retrospectives were mounted at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (1994), and at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebaek, Denmark (2007; which traveled to Milan, Paris, Berlin, Amsterdam and San Francisco, through 2009). Showing Avedon's work from his earliest, sun-splashed pictures in 1944 to portraits in 2000 that convey his fashion fatigue, the International Center of Photography in 2009 mounted the largest survey of his fashion work.[18] Also in 2009, the Corcoran Gallery of Art showed Richard Avedon: Portraits of Power, bringing together the his political portraits for the first time.[19]

Collections

Avedon's work is held in the following permanent collections:

- Museum of Modern Art, New York [1]

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York [1]

- Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, Washington, D.C.[1][5]

- Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Ft. Worth, Texas [1]

- Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris

- Israel Museum, Jerusalem. Supported by Leonard A. Lauder and Larry Gagosian, the Avedon Foundation gave 74 Avedon images to the Israel Museum in 2013.[20]

Awards

- 1989: Lifetime Achievement Award from the Council of Fashion Designers of America

- 1989: Honorary graduate degree from the Royal College of Art

- 1993: Honorary graduate degree from the Kenyon College

- 1993: International Center of Photography's Master of Photography Award

- 1994: Honorary graduate degree from the Parsons School of Design

- 1994: Prix Nadar in for his book Evidence (1994)

- 2001: Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences[21]

- 2003: Kitty Carlisle Hart Award, Arts & Business Council, New York[22]

- 2003: Royal Photographic Society 150th Anniversary Medal

- 2003: National Arts Award for Lifetime Achievement

- 2003: The Royal Photographic Society's Special 150th Anniversary Medal and Honorary Fellowship (HonFRPS)[23]

Art market

In 2010, a record price of £719,000 was achieved at Christie's for a unique seven-foot-high print of model Dovima, posing in a Christian Dior evening dress with elephants from the Cirque d’Hiver, Paris, in 1955. This particular print, the largest of this image, was made in 1978 for Avedon’s fashion retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and was bought by Maison Christian Dior.[24]

Personal life and death

In 1944, Avedon married 19-year-old bank teller Dorcas Marie Nowell who later became the model and actress Doe Avedon; they did not have children and divorced in 1949.[25] In 1951, he married Evelyn Franklin; she died on March 13, 2004.[26] Their marriage produced one son, John Avedon, who has written extensively about Tibet.[27][28][29][30]

In 1970, Avedon purchased a former carriage house on the Upper East Side of Manhattan that would serve as both his studio and apartment.[31] In the late 1970s, he purchased a four-bedroom house on a 7.5-acre (3.0 ha) estate in Montauk, New York, between the Atlantic Ocean and a nature preserve; he sold it for almost $9 million in 2000.[30][32]

On October 1, 2004, Avedon died in a San Antonio, Texas hospital of complications from a cerebral hemorrhage. He was in San Antonio shooting an assignment for The New Yorker. At the time of his death, he was also working on a new project titled Democracy to focus on the run-up to the 2004 U.S. presidential election.[1]

Legacy

The Richard Avedon Foundation is a private operating foundation, structured by Avedon during his lifetime. It began its work shortly after his death in 2004. Based in New York, the foundation is the repository for Avedon's photographs, negatives, publications, papers, and archival materials.[33] In 2006, Avedon's personal collection was shown at the Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York, and at the Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco, and later sold to benefit the Avedon Foundation. The collection included photographs by Martin Munkacsi, Edward Steichen and Man Ray, among others. A slender volume, Eye of the Beholder: Photographs From the Collection of Richard Avedon (Fraenkel Gallery), assembles the majority of the collection in a boxed set of five booklets: “Diane Arbus,” “Peter Hujar”, “Irving Penn”, “The Countess de Castiglione” and “Etcetera,” which includes 19th- and 20th-century photographers.[34]

In popular culture

Hollywood presented a fictional account of Avedon's early career in the 1957 musical Funny Face, starring Fred Astaire as the fashion photographer "Dick Avery." Avedon supplied some of the still photographs used in the production, including its most noted single image: an intentionally overexposed close-up of Audrey Hepburn's face in which only her noted features – her eyes, her eyebrows, and her mouth – are visible.

Hepburn was Avedon's muse in the 1950s and 1960s, and he went so far as to say: "I am, and forever will be, devastated by the gift of Audrey Hepburn before my camera. I cannot lift her to greater heights. She is already there. I can only record. I cannot interpret her. There is no going further than who she is. She has achieved in herself her ultimate portrait."[35]

Noted photographs

- Marella Agnelli, Italian socialite, 1953

- Carmen Mayrink Veiga, Brazilian socialite (Vogue's 10 best dressed), 1970

- Dovima with Elephants, 1955

- Marilyn Monroe, actress, 1957

- Homage to Munkacsi, Carmen, coat by Cardin, Paris, 1957

- Brigitte Bardot, actress, 1959

- Jacqueline de Ribes, 1961

- Christina Bellin, model, 1962

- Kareem Abdul-Jabbar (Lew Alcindor), athlete 1963

- Dwight David Eisenhower, President of the United States, 1964

- The Beatles, 1967

- Andy Warhol and Members of the Factory, New York, 1969

- Sly Stone (cover of the album Fresh), 1973

- Asha Puthli, (She Loves to Hear the Music Album back cover), 1974

- Ronald Fischer, beekeeper, 1981

- Nastassja Kinski and the Serpent, 1981[36]

- Pile of beautiful people, Versace campaign, 1982

- Whitney Houston (cover of Whitney), 1987

Books

- Observations. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1959. Photographs by Avedon, commentary by Truman Capote. Portraits of noted people.

- Nothing Personal. New York: Atheneum: 1964. A collaborative book with James Baldwin.

- Alice in Wonderland: The Forming of a Company and the Making of a Play. Merlin: 1973. By Avedon and Doon Arbus. ISBN 978-0-88306-500-6.

- Portraits. Noonday: 1976. Introduction by Harold Rosenberg. ISBN 978-0-374-51412-9.

- Portraits 1947–1977. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1978. ISBN 978-0-374-23200-9.

- In the American West.

- In the American West, Photographs by Richard Avedon. New York: Abrams, 1985. With an introduction by Laura Wilson. Published in conjunction with an exhibition at Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, TX.

- In the American West, 1979–1984. New York: Abrams, 1985. ISBN 978-0-8109-2301-0.

- In the American West: 20th Anniversary Edition. New York: Abrams, 2005. ISBN 978-0-8109-5928-6.

- An Autobiography. 1993. Photographs arranged to tell Avedon's life story.

- Evidence. 1994. Essays and text about Avedon with photographs by Avedon.

- The Sixties. 1999. By Avedon and Doon Arbus. Photographs of noted people.

- Made in France, 2001. A retrospective of Avedon's fashion portraiture from the 1950s.

- Richard Avedon Portraits' 2002. Celebrities and subjects from In The American West. Published in conjunction with an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Woman in the Mirror. 2005. With an essay by Anne Hollander.

- Performance. 2008. With an essay by John Lahr.

- Portraits of Power. 2008. Edited by Paul Roth. With an essay by Renata Adler. Published in conjunction with an exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Richard Avedon, the Eye of Fashion, Dies at 81", Andy Grundberg, The New York Times, October 1, 2004.

- 1 2 Paula Chin (May 23, 1994), At 71, Assailed by Critics, the Prickly Photographer Says Frankly, 'I Don't Give a Damn How I'm Taken.' People.

- 1 2 "Richard Avedon biography". Biography Channel. Retrieved March 22, 2013.

- 1 2 Rourke, Mary. "Photographer Richard Avedon Dies". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 22, 2013.

- 1 2 Staff (October 2, 2004). "Richard Avedon". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved September 14, 2009. "He also edited the school magazine at DeWitt Clinton High, on which the black American writer James Baldwin was literary editor."

- ↑ Richard Avedon MoMA, New York.

- ↑ William Ahearn (October 1, 2004), Richard Avedon, Portrait and Fashion Photographer, Dies at 81 Bloomberg.

- 1 2 Holland Cotter (July 5, 2012), Richard Avedon: ‘Murals & Portraits’ New York Times.

- ↑ Elizabeth Sussman; Doon Arbus (2011). Diane Arbus: A Chronology. New York: Aperture Foundation. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-59711-179-9.

- 1 2 3 4 Whitney, Helen. "Richard Avedon: Darkness and Light". American Masters. PBS.

- ↑ Richard Avedon: Murals & Portraits, May 4 – July 6, 2012 Gagosian Gallery, New York.

- ↑ "Advertising; Phase 3 Of Wild Dior Antics". The New York Times. 11 July 1983.

- ↑ Women's Wear Daily, October 2004.

- ↑ Turner-Yamamoto, Judith (May 2006). "In Avedon's American West". World and I Journal.

- 1 2 3 4 Pénichon, Sylvie (2008). "The Making of the American West". The American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works. 3. 47: 175.

- 1 2 Dubiel, Richard (1989). "Existential Approach to Art and Value". National Art Education Association. 3. 42: 19. JSTOR 3193139.

- ↑ "Once at MIA: Avedon sits in — Minneapolis Institute of Art – Minneapolis Institute of Art". Minneapolis Institute of Art.

- ↑ Cathy Horn (May 13, 2009), How Avedon Blurred His Own Image New York Times.

- ↑ Richard Avedon: Portraits of Power Corcoran Gallery, Washington, D.C.

- ↑ Carol Vogel (September 5, 2013), Richard Avedon Portraits Go to Israel Museum New York Times.

- ↑ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter A" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- ↑ Robishaw, Lori; Gard Ewell, Maryo (2011). Commemorating 50 Years of Americans for the Arts. Americans for the Arts. p. 124. ISBN 978-1-879903-07-4.

- ↑ Royal Photographic Society's Centenary Award Accessed August 13, 2012.

- ↑ Colin Gleadell (November 22, 2010), "New record for Richard Avedon photography sales", The Daily Telegraph.

- ↑ Ronald Bergan (26 December 2011). "Doe Avedon obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 2013-06-26.

- ↑ "Paid Notice: Deaths AVEDON, EVELYN FRANKLIN". The New York Times. March 16, 2004.

- ↑ The Buddha's Art of Healing: Tibetan Paintings Rediscovered, John Avedon, Rizzoli, 1998.

- ↑ Exploring the Mysteries of Tibetan Medicine, John Avedon, The New York Times Magazine, January 11, 1981.

- ↑ Donald G. McNeil Jr. (November 26, 1984), His Father's Photos Extol Beauty, but John Avedon's New Book on Tibet Doesn't Paint a Pretty Picture People.

- 1 2 Deborah Netburn (April 24, 2000), Avedon Gets $9 Million From East End Couple For His Montauk Spread New York Observer.

- ↑ Wendy Goodman (May 21, 2005), The Interior World of Richard Avedon New York Magazine.

- ↑ Alex Williams (August 9, 1999), Big Shack Attack New York Magazine.

- ↑ Richard Avedon Gagosian Gallery, New York.

- ↑ Philip Gefter (August 27, 2006), In Portraits by Others, a Look That Caught Avedon’s Eye New York Times.

- ↑ Karney, Robyn. A Star Danced: The Life of Audrey Hepburn, London: Bloomsbury, 1993.

- ↑ Welsh, James Michael ; Gene D. Phillips; Rodney Hill The Francis Ford Copolla Encyclopedia Scarecrow Press Lanham, Maryland 2010, p. 154.

External links

- Official website

- Richard Avedon Biography

- Richard Avedon at Encyclopædia Britannica

- Richard Avedon at the Museum of Modern Art

- Richard Avedon at Find a Grave

- Richard Avedon: Portrait Series of Jacob Israel Avedon from the Collection of The Jewish Museum (New York)