Marilyn Monroe

| Marilyn Monroe | |

|---|---|

Monroe c. 1953 | |

| Born |

Norma Jeane Mortenson June 1, 1926 Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Died |

August 5, 1962 (aged 36) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Barbiturate overdose |

| Resting place | Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery |

| Other names | Norma Jeane Baker |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1945–62 |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Website |

marilynmonroe |

| Signature | |

|

| |

Marilyn Monroe (born Norma Jeane Mortenson; June 1, 1926 – August 5, 1962) was an American actress and model. Famous for playing comic "dumb blonde" characters, she became one of the most popular sex symbols of the 1950s, emblematic of the era's attitudes towards sexuality. Although she was a top-billed actress for only a decade, her films grossed $200 million by the time of her unexpected death in 1962.[1] She continues to be considered a major popular culture icon.[2]

Born and raised in Los Angeles, Monroe spent most of her childhood in foster homes and an orphanage and married at the age of sixteen. While working in a factory in 1944 as part of the war effort, she was introduced to a photographer from the First Motion Picture Unit and began a successful pin-up modeling career. The work led to short-lived film contracts with Twentieth Century-Fox (1946–47) and Columbia Pictures (1948). After a series of minor film roles, she signed a new contract with Fox in 1951. Over the next two years, she became a popular actress with roles in several comedies, including As Young as You Feel and Monkey Business, and in the dramas Clash by Night and Don't Bother to Knock. Monroe faced a scandal when it was revealed that she had posed for nude photos before becoming a star, but rather than damaging her career, the story increased interest in her films.

By 1953, Monroe was one of the most marketable Hollywood stars, with leading roles in three films: the noir Niagara, which focused on her sex appeal, and the comedies Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and How to Marry a Millionaire, which established her star image as a "dumb blonde". Although she played a significant role in the creation and management of her public image throughout her career, she was disappointed at being typecast and underpaid by the studio. She was briefly suspended in early 1954 for refusing a film project, but returned to star in one of the biggest box office successes of her career, The Seven Year Itch (1955).

When the studio was still reluctant to change her contract, Monroe founded a film production company in late 1954, Marilyn Monroe Productions (MMP). She dedicated 1955 to building her company and began studying method acting at the Actors Studio. In late 1955, Fox awarded her a new contract, which gave her more control and a larger salary. After a critically acclaimed performance in Bus Stop (1956) and acting in the first independent production of MMP, The Prince and the Showgirl (1957), she won a Golden Globe for Best Actress for Some Like It Hot (1959). Her last completed film was the drama The Misfits (1961).

Monroe's troubled private life received much attention. She struggled with substance abuse, depression, and anxiety. She had two highly publicized marriages, to retired baseball star Joe DiMaggio and playwright Arthur Miller, both of which ended in divorce. She died at the age of 36 on August 5, 1962 from an overdose of barbiturates at her home in Los Angeles. Although the death was ruled a probable suicide, several conspiracy theories have been proposed in the decades following her death.

Life and career

Childhood and first marriage (1926–1944)

Monroe was born Norma Jeane Mortenson at the Los Angeles County Hospital on June 1, 1926, as the third child of Gladys Pearl Baker (née Monroe, 1902–84).[3] Gladys, the daughter of two poor Midwestern migrants to California, was a flapper and worked as a film negative cutter at Consolidated Film Industries.[4] When she was fifteen, Gladys married a man nine years her senior, John Newton Baker, and had two children by him, Robert (1917–33)[5] and Berniece (born 1919).[6] She filed for divorce in 1921, and Baker took the children with him to his native Kentucky.[7] Monroe was not told that she had a sister until she was twelve, and met her for the first time as an adult.[8] Gladys married her second husband Martin Edward Mortensen in 1924, but they separated before she became pregnant with Monroe; they divorced in 1928.[9] The identity of Monroe's father is unknown and Baker was most often used as her surname.[10][lower-alpha 1]

Monroe's early childhood was stable and happy.[14] While Gladys was mentally and financially unprepared for a child, she was able to place Monroe with foster parents Albert and Ida Bolender in the rural town of Hawthorne soon after the birth.[15] They raised their foster children according to the principles of evangelical Christianity.[14] At first, Gladys lived with the Bolenders and commuted to work in Los Angeles, until longer work shifts forced her to move back to the city in early 1927.[16] She then began visiting her daughter on weekends, often taking her to the cinema and to sightsee in Los Angeles.[14] Although the Bolenders wanted to adopt Monroe, by the summer of 1933, Gladys felt stable enough for Monroe to move in with her and bought a small house in Hollywood.[17] They shared it with lodgers, actors George and Maude Atkinson and their daughter, Nellie.[18] Some months later, in January 1934, Gladys had a mental breakdown and was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia.[19] After several months in a rest home, she was committed to the Metropolitan State Hospital.[20] She spent the rest of her life in and out of hospitals, and was rarely in contact with Monroe.[21]

"When I was five I think, that's when I started wanting to be an actress. I loved to play. I didn't like the world around me because it was kind of grim, but I loved to play house. It was like you could make your own boundaries... When I heard that this was acting, I said that's what I want to be... Some of my foster families used to send me to the movies to get me out of the house and there I'd sit all day and way into the night. Up in front, there with the screen so big, a little kid all alone, and I loved it."[22]

—Monroe in an interview for Life in 1962

Monroe was declared a ward of the state, and her mother's friend, Grace McKee Goddard, took responsibility over her and her mother's affairs.[23] In the following four years, she lived with several foster families, and often switched schools. For the first sixteen months, she continued living with the Atkinsons; she was sexually abused during this time.[24][lower-alpha 2] Always a shy girl, she now also developed a stutter and became withdrawn.[30] In the summer of 1935, she briefly stayed with Grace and her husband Erwin "Doc" Goddard and two other families,[31] until Grace placed her in the Los Angeles Orphans Home in Hollywood in September 1935.[32] While the orphanage was "a model institution", and was described in positive terms by her peers, Monroe found being placed there traumatizing, as to her "it seemed that no one wanted me".[33]

Encouraged by the orphanage staff, who thought that Monroe would be happier living in a family, Grace became her legal guardian in 1936, although she was not able to take her out of the orphanage until the summer of 1937.[34] Monroe's second stay with the Goddards lasted only a few months, as Doc molested her.[35] After staying with various of her and Grace's relatives and friends in Los Angeles and Compton,[36] Monroe found a more permanent home in September 1938, when she began living with Grace's aunt, Ana Atchinson Lower, in the Sawtelle district.[37] She was enrolled in Emerson Junior High School and was taken to weekly Christian Science services with Lower.[38] While otherwise a mediocre student, Monroe excelled in writing and contributed to the school's newspaper.[39] Due to the elderly Lower's health issues, Monroe returned to live with the Goddards in Van Nuys in either late 1940 or early 1941.[40] After graduating from Emerson, she began attending Van Nuys High School.[41]

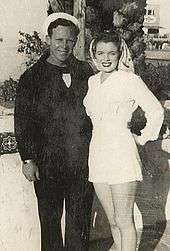

In early 1942, the company that Doc Goddard worked for required him to relocate to West Virginia.[42] California laws prevented the Goddards from taking Monroe out of state, and she faced the possibility of having to return to the orphanage.[43] As a solution, she married their neighbors' son, 21-year-old factory worker James "Jim" Dougherty, on June 19, 1942, just after her 16th birthday.[44] Monroe subsequently dropped out of high school and became a housewife; she later stated that the "marriage didn't make me sad, but it didn't make me happy, either. My husband and I hardly spoke to each other. This wasn't because we were angry. We had nothing to say. I was dying of boredom."[45] In 1943, Dougherty enlisted in the Merchant Marine.[46] He was initially stationed on Catalina Island, where she lived with him until he was shipped out to the Pacific in April 1944; he would remain there for most of the next two years.[46] After Dougherty's departure, Monroe moved in with his parents and began working at the Radioplane Munitions Factory to participate in the war effort and to earn her own income.[46]

Modeling and first film roles (1945–1949)

In late 1944, Monroe met photographer David Conover, who had been sent by the U.S. Army Air Forces' First Motion Picture Unit (FMPU) to the factory to shoot morale-boosting pictures of female workers.[47] Although none of her pictures were used by the FMPU, she quit working at the factory in January 1945 and began modeling for Conover and his friends.[48][49] She moved out of her in-laws' home, defying them and her husband, and signed a contract with the Blue Book Model Agency in August 1945.[50] She began to occasionally use the name Jean Norman when working, and had her curly brunette hair straightened and dyed blond to make her more employable.[51] As her figure was deemed more suitable for pin-up than fashion modeling, she was employed mostly for advertisements and men's magazines.[52] According to the agency's owner, Emmeline Snively, Monroe was one of its most ambitious and hard-working models; by early 1946, she had appeared on 33 magazine covers for publications such as Pageant, U.S. Camera, Laff, and Peek.[53]

Impressed by her success, Snively arranged a contract for Monroe with an acting agency in June 1946.[54] After an unsuccessful interview with producers at Paramount Pictures, she was given a screentest by Ben Lyon, a 20th Century-Fox executive. Head executive Darryl F. Zanuck was unenthusiastic about it,[55] but he was persuaded to give her a standard six-month contract to avoid her being signed by rival studio RKO Pictures.[lower-alpha 3] Monroe began her contract in August 1946, and together with Lyon selected the stage name "Marilyn Monroe".[57] The first name was picked by Lyon, who was reminded of Broadway star Marilyn Miller; the last was picked by Monroe after her mother's maiden name.[58] In September 1946, she divorced Dougherty, who was against her having a career.[59]

Monroe had no film roles during the first months of her contract and instead dedicated her days to acting, singing and dancing classes.[60] Eager to learn more about the film industry and to promote herself, she also spent time at the studio lot to observe others working.[61] Her contract was renewed in February 1947, and she was soon given her first two film roles: nine lines of dialogue as a waitress in the drama Dangerous Years (1947) and a one-line appearance in the comedy Scudda Hoo! Scudda Hay! (1948).[62][lower-alpha 4] The studio also enrolled her in the Actors' Laboratory Theatre, an acting school teaching the techniques of the Group Theatre; she later stated that it was "my first taste of what real acting in a real drama could be, and I was hooked".[64] Monroe's contract was not renewed in August 1947, and she returned to modeling while also doing occasional odd jobs at the studio.[65]

Determined to make it as an actress, Monroe continued studying at the Actors' Lab, and in October appeared as a blonde vamp in the short-lived play Glamour Preferred at the Bliss-Hayden Theater, but the production was not reviewed by any major publication.[66] To promote herself, she frequented producers' offices, befriended gossip columnist Sidney Skolsky, and entertained influential male guests at studio functions, a practice she had begun at Fox.[67] She also became a friend and occasional sex partner of Fox executive Joseph M. Schenck, who persuaded his friend Harry Cohn, the head executive of Columbia Pictures, to sign her in March 1948.[68]

While at Fox her roles had been that of a "girl next door", at Columbia she was modeled after Rita Hayworth.[69] Monroe's hairline was raised by electrolysis and her hair was bleached even lighter, to platinum blond.[70] She also began working with the studio's head drama coach, Natasha Lytess, who would remain her mentor until 1955.[70] Her only film at the studio was the low-budget musical Ladies of the Chorus (1948), in which she had her first starring role as a chorus girl who is courted by a wealthy man.[63] During the production, she began an affair with her vocal coach, Fred Karger, who paid to have her slight overbite corrected.[71] Despite the starring role and a subsequent screen test for the lead role in Born Yesterday (1950), Monroe's contract was not renewed.[72] Ladies of the Chorus was released in October and was not a success.[73]

After leaving Columbia in September 1948, Monroe became a protégée of Johnny Hyde, vice president of the William Morris Agency. Hyde began representing her and their relationship soon became sexual, although she refused his proposals of marriage.[74] To advance Monroe's career, he paid for a silicone prosthesis to be implanted in her jaw and possibly for a rhinoplasty, and arranged a bit part in the Marx Brothers film Love Happy (1950).[75] Monroe also continued modeling, and in May 1949 posed for nude photos taken by Tom Kelley.[76] Although her role in Love Happy was very small, she was chosen to participate in the film's promotional tour in New York that year.[77]

Breakthrough (1950–1952)

Monroe appeared in six films released in 1950. She had bit parts in Love Happy, A Ticket to Tomahawk, Right Cross and The Fireball, but also made minor appearances in two critically acclaimed films: John Huston's crime film The Asphalt Jungle and Joseph Mankiewicz's drama All About Eve.[78] In the former, Monroe played Angela, the young mistress of an aging criminal.[79] Although only on the screen for five minutes, she gained a mention in Photoplay and according to Spoto "moved effectively from movie model to serious actress".[79] In All About Eve, Monroe played Miss Caswell, a naïve young actress.[80]

Following Monroe's success in these roles, Hyde negotiated a seven-year contract with 20th Century-Fox in December 1950.[81] He died of a heart attack only days later, leaving her devastated.[82] Despite her grief, 1951 became the year in which she gained more visibility. In March, she was a presenter at the 23rd Academy Awards, and in September, Collier's became the first national magazine to publish a full-length profile of her.[83] She had supporting roles in four low-budget films: in the MGM drama Home Town Story, and in three moderately successful comedies for Fox, As Young as You Feel, Love Nest, and Let's Make It Legal.[84] According to Spoto all four films featured her "essentially [as] a sexy ornament", but she received some praise from critics: Bosley Crowther of The New York Times described her as "superb" in As Young As You Feel and Ezra Goodman of the Los Angeles Daily News called her "one of the brightest up-and-coming [actresses]" for Love Nest.[85] To further develop her acting skills, Monroe began taking classes with Michael Chekhov and mime Lotte Goslar.[86] Her popularity with audiences was also growing: she received several thousand letters of fan mail a week, and was declared "Miss Cheesecake of 1951" by the army newspaper Stars and Stripes, reflecting the preferences of soldiers in the Korean War.[87] In her private life, Monroe was in a relationship with director Elia Kazan, and also briefly dated several other men, including director Nicholas Ray and actors Yul Brynner and Peter Lawford.[88]

.jpg)

The second year of the Fox contract saw Monroe become a top-billed actress, with gossip columnist Florabel Muir naming her the year's "it girl" and Hedda Hopper describing her as the "cheesecake queen" turned "box office smash".[89][90] In February, she was named the "best young box office personality" by the Foreign Press Association of Hollywood,[91] and began a highly publicized romance with retired New York Yankee Joe DiMaggio, one of the most famous sports personalities of the era.[92] The following month, a scandal broke when she revealed in an interview that she had posed for nude pictures in 1949, which were featured in calendars.[93] The studio had learned of the photographs some weeks earlier, and to contain the potentially disastrous effects on her career, they and Monroe had decided to talk about them openly while stressing that she had only posed for them in a dire financial situation.[94] The strategy succeeded in getting her public sympathy and increased interest in her films: the following month, she was featured on the cover of Life as "The Talk of Hollywood".[95] Monroe added to her reputation as a new sex symbol with other publicity stunts that year, such as wearing a revealing dress when acting as Grand Marshal at the Miss America Pageant parade, and by stating to gossip columnist Earl Wilson that she usually wore no underwear.[96]

Regardless of the popularity her sex appeal brought, Monroe wished to present more of her acting range, and in the summer of 1952 she appeared in two commercially successful dramas.[97] The first was Fritz Lang's Clash by Night, for which she was loaned to RKO and played a fish cannery worker; to prepare, she spent time in a real fish cannery in Monterey.[98] She received positive reviews for her performance: The Hollywood Reporter stated that "she deserves starring status with her excellent interpretation", and Variety wrote that she "has an ease of delivery which makes her a cinch for popularity".[99][100] The second film was the thriller Don't Bother to Knock, in which she starred as a mentally disturbed babysitter and which Zanuck had assigned for her to test her abilities in a heavier dramatic role.[101] It received mixed reviews from critics, with Crowther deeming her too inexperienced for the difficult role,[102] and Variety blaming the script for the film's problems.[103][104]

Monroe's three other films in 1952 continued her typecasting in comic roles which focused on her sex appeal. In We're Not Married!, her starring role as a beauty pageant contestant was created solely to "present Marilyn in two bathing suits", according to its writer Nunnally Johnson.[105] In Howard Hawks' Monkey Business, in which she was featured opposite Cary Grant, she played a secretary who is a "dumb, childish blonde, innocently unaware of the havoc her sexiness causes around her".[106] In O. Henry's Full House, her final film of the year, she had a minor role as a prostitute.[106]

During this period Monroe gained a reputation for being difficult on film sets, which worsened as her career progressed: she was often late or did not show up at all, did not remember her lines, and would demand several re-takes before she was satisfied with her performance.[107] A dependence on her acting coaches, first Natasha Lytess and later Paula Strasberg, also irritated directors.[108] Monroe's problems have been attributed to a combination of perfectionism, low self-esteem, and stage fright; she disliked the lack of control she had on her work on film sets, and never experienced similar problems during photo shoots, in which she had more say over her performance and could be more spontaneous instead of following a script.[109][110] To alleviate her anxiety and chronic insomnia, she began to use barbiturates, amphetamines and alcohol, which also exacerbated her problems, although she did not become severely addicted until 1956.[111] According to Sarah Churchwell, some of Monroe's behavior especially later in her career was also in response to the condescension and sexism of her male co-stars and directors.[112] Similarly, Lois Banner has stated that she was bullied by many of her directors.[113]

Rising star (1953)

Monroe starred in three movies released in 1953, emerging as a major sex symbol and one of Hollywood's most bankable performers.[114][115] The first of these was the Technicolor film noir Niagara, in which she played a femme fatale scheming to murder her husband, played by Joseph Cotten.[116] By then, Monroe and her make-up artist Allan "Whitey" Snyder had developed the make-up look that became associated with her: dark arched brows, pale skin, "glistening" red lips and a beauty mark.[117] According to Sarah Churchwell, Niagara was one of the most overtly sexual films of Monroe's career, and it included scenes in which her body was covered only by a sheet or a towel, considered shocking by contemporary audiences.[118] Its most famous scene is a 30-second long shot of Monroe shown walking from behind with her hips swaying, which was heavily used in the film's marketing.[118]

Upon Niagara's release in January, women's clubs protested against it as immoral, but it proved popular with audiences, grossing $6 million in the box office.[119] While Variety deemed it "clichéd" and "morbid", The New York Times commented that "the falls and Miss Monroe are something to see", as although Monroe may not be "the perfect actress at this point ... she can be seductive – even when she walks".[120][121] Monroe continued to attract attention with her revealing outfits in publicity events, most famously at the Photoplay awards in January 1953, where she won the "Fastest Rising Star" award.[122] She wore a skin-tight gold lamé dress, which prompted veteran star Joan Crawford to describe her behavior as "unbecoming an actress and a lady" to the press.[122]

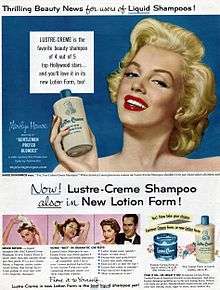

.jpg)

While Niagara made Monroe a sex symbol and established her "look", her second film of the year, the satirical musical comedy Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, established her screen persona as a "dumb blonde".[123] Based on Anita Loos' bestselling novel and its Broadway version, the film focuses on two "gold-digging" showgirls, Lorelei Lee and Dorothy Shaw, played by Monroe and Jane Russell. The role of Lorelei was originally intended for Betty Grable, who had been 20th Century-Fox's most popular "blonde bombshell" in the 1940s; Monroe was fast eclipsing her as a star who could appeal to both male and female audiences.[124] As part of the film's publicity campaign, she and Russell pressed their hand and footprints in wet concrete outside Grauman's Chinese Theatre in June.[125] Gentlemen Prefer Blondes was released shortly after and became one of the biggest box office successes of the year by grossing $5.3 million, more than double its production costs.[126] Crowther of The New York Times and William Brogdon of Variety both commented favorably on Monroe, especially noting her performance of "Diamonds Are a Girl's Best Friend"; according to the latter, she demonstrated the "ability to sex a song as well as point up the eye values of a scene by her presence".[127][128]

In September, Monroe made her television debut in the Jack Benny Show, playing Jack's fantasy woman in the episode "Honolulu Trip".[129] Her third movie of the year, How to Marry a Millionaire, co-starred Betty Grable and Lauren Bacall and was released in November. It featured Monroe in the role of a naïve model who teams up with her friends to find rich husbands, repeating the successful formula of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. It was the second film ever released in CinemaScope, a widescreen format which Fox hoped would draw audiences back to theaters as television was beginning to cause losses to film studios.[130] Despite mixed reviews, the film was Monroe's biggest box office success so far, earning $8 million in world rentals.[131]

Monroe was listed in the annual Top Ten Money Making Stars Poll in both 1953 and 1954,[115] and according to Fox historian Aubrey Solomon became the studio's "greatest asset" alongside CinemaScope.[132] Monroe's position as a leading sex symbol was confirmed in December, when Hugh Hefner featured her on the cover and as centerfold in the first issue of Playboy.[133] The cover image was a shot of her at the Miss America Pageant parade in 1952, and the centerfold featured one of her 1949 nude photographs.[133]

Conflicts with 20th Century-Fox and marriage to Joe DiMaggio (1954–1955)

Although Monroe had become one of 20th Century-Fox's biggest stars, her contract had not changed since 1950, meaning that she was paid far less than other stars of her stature and could not choose her projects or co-workers.[134] She was also tired of being typecast, and her attempts to appear in films other than comedies or musicals had been thwarted by Zanuck, who had a strong personal dislike of her and did not think she would earn the studio as much revenue in dramas.[135] When she refused to begin shooting yet another musical comedy, a film version of The Girl in Pink Tights, which was to co-star Frank Sinatra, the studio suspended her on January 4, 1954.[136]

The suspension was front page news and Monroe immediately began a publicity campaign to counter any negative press and to strengthen her position in the conflict. On January 14, she and Joe DiMaggio, whose relationship had been subject to constant media attention since 1952, were married at the San Francisco City Hall.[137] They then traveled to Japan, combining a honeymoon with his business trip.[138] From there, she traveled alone to Korea, where she performed songs from her films as part of a USO show for over 60,000 U.S. Marines over a four-day period.[139] After returning to Hollywood in February, she was awarded Photoplay's "Most Popular Female Star" prize.[140] She reached a settlement with the studio in March: it included a new contract to be made later in the year, and a starring role in the film version of the Broadway play The Seven Year Itch, for which she was to receive a bonus of $100,000.[141]

The following month saw the release of Otto Preminger's Western River of No Return, in which Monroe appeared opposite Robert Mitchum. She called it a "Z-grade cowboy movie in which the acting finished second to the scenery and the CinemaScope process", although it was popular with audiences.[142] The first film she made after returning to Fox was the musical There's No Business Like Show Business, which she strongly disliked but the studio required her to do in exchange for dropping The Girl in Pink Tights.[141] The musical was unsuccessful upon its release in December, and Monroe's performance was considered vulgar by many critics.[143]

In September 1954, Monroe began filming Billy Wilder's comedy The Seven Year Itch, in which she starred opposite Tom Ewell as a woman who becomes the object of her married neighbor's sexual fantasies. Although the film was shot in Hollywood, the studio decided to generate advance publicity by staging the filming of a scene on Lexington Avenue in New York.[144] In the shoot, Monroe is standing on a subway grate with the air blowing up the skirt of her white dress, which became one of the most famous scenes of her career. The shoot lasted for several hours and attracted a crowd of nearly 2,000 spectators, including professional photographers.[144]

While the publicity stunt placed Monroe on front pages all over the world, it also marked the end of her marriage to DiMaggio, who was furious about it.[145] The union had been troubled from the start by his jealousy and controlling attitude; Spoto and Banner have also asserted that he was physically abusive.[146] After returning to Hollywood, Monroe hired famous attorney Jerry Giesler and announced in October 1954 that she was filing for divorce.[147] The Seven Year Itch was released the following June, and grossed over $4.5 million at the box office, making it one of the biggest commercial successes that year.[148]

After filming for Itch wrapped in November, Monroe began a new battle for control over her career and left Hollywood for the East Coast, where she and photographer Milton Greene founded their own production company, Marilyn Monroe Productions (MMP) – an action that has later been called "instrumental" in the collapse of the studio system.[149][lower-alpha 5] Announcing its foundation in a press conference in January 1955, Monroe stated that she was "tired of the same old sex roles. I want to do better things. People have scope, you know."[151] She asserted that she was no longer under contract to Fox, as the studio had not fulfilled its duties, such as paying her the promised bonus for The Seven Year Itch.[152] This began a year-long legal battle between her and the studio.[153] The press largely ridiculed Monroe for her actions and she was parodied in Itch writer George Axelrod's Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? (1955), in which her lookalike Jayne Mansfield played a dumb actress who starts her own production company.[154]

Monroe dedicated 1955 to studying her craft. She moved to New York and began taking acting classes with Constance Collier and attending workshops on method acting at the Actors Studio, run by Lee Strasberg.[155] She sometimes jotted down private notes to herself of what she learned on a given day, acknowledging that Strasberg's observations about her in particular were important:

Why did it mean so much to me?... Strasberg makes me feel badly [that I was acting out of "fear"]... You must start to do things out of strength... by not looking for strength, but only looking and seeking technical ways and means.[156]

She grew close to Strasberg and his wife Paula, receiving private lessons at their home due to her shyness, and soon became like a family member.[157] She dismissed her old drama coach, Natasha Lytess, and replaced her with Paula; the Strasbergs remained an important influence for the rest of her career.[158] Monroe also started undergoing psychoanalysis at the recommendation of Strasberg, who believed that an actor must confront their emotional traumas and use them in their performances.[159][lower-alpha 6]

In her private life, Monroe continued her relationship with DiMaggio despite the ongoing divorce proceedings while also dating actor Marlon Brando and playwright Arthur Miller.[161] She had first been introduced to Miller by Kazan in the early 1950s.[161] The affair between Monroe and Miller became increasingly serious after October 1955, when her divorce from DiMaggio was finalized, and Miller separated from his wife.[162] The FBI also opened a file on her.[162] The studio feared that Monroe would be blacklisted and urged her to end the affair, as Miller was being investigated by the FBI for allegations of communism and had been subpoenaed by the House Un-American Activities Committee.[163][164] Despite the risk to her career, Monroe refused to end the relationship, later calling the studio heads "born cowards".[165]

By the end of the year, Monroe and Fox had come to an agreement about a new seven-year contract. It was clear that MMP would not be able to finance films alone, and the studio was eager to have Monroe working again.[153] The contract required her to make four movies for Fox during the seven years.[166] The studio would pay her $100,000 for each movie, and granted her the right to choose her own projects, directors and cinematographers.[166] She would also be free to make one film with MMP per each completed film for Fox.[166]

Critical acclaim and marriage to Arthur Miller (1956–1959)

Monroe began 1956 by announcing her win over 20th Century-Fox; the press, which had previously derided her, now wrote favorably about her decision to fight the studio.[167] Time called her a "shrewd businesswoman"[168] and Look predicted that the win would be "an example of the individual against the herd for years to come".[167] She also officially changed her name to Marilyn Monroe in March.[169] Her relationship with Miller prompted some negative comments from the press, including Walter Winchell's statement that "America's best-known blonde moving picture star is now the darling of the left-wing intelligentsia."[170] Monroe and Miller were married in a civil ceremony at the Westchester County Court in White Plains, New York on June 29, and two days later had a Jewish ceremony at his agent's house at Waccabuc, New York.[171][172] Monroe converted to Judaism with the marriage, which led Egypt to ban all of her films.[173][lower-alpha 7] The media saw the union as mismatched given her star image as a sex symbol and his position as an intellectual, as demonstrated by Variety's headline "Egghead Weds Hourglass".[175]

The first film that Monroe chose to make under the new contract was the drama Bus Stop, released in August 1956. She played Chérie, a saloon singer whose dreams of stardom are complicated by a naïve cowboy who falls in love with her. For the role, she learnt an Ozark accent, chose costumes and make-up that lacked the glamour of her earlier films, and provided deliberately mediocre singing and dancing.[176] Broadway director Joshua Logan agreed to direct, despite initially doubting her acting abilities and knowing of her reputation for being difficult.[177] The filming took place in Idaho and Arizona in early 1956, with Monroe "technically in charge" as the head of MMP, occasionally making decisions on cinematography and with Logan adapting to her chronic lateness and perfectionism.[178]

The experience changed Logan's opinion of Monroe, and he later compared her to Charlie Chaplin in her ability to blend comedy and tragedy.[179] Bus Stop became a box office success, grossing $4.25 million, and received mainly favorable reviews.[180] The Saturday Review of Literature wrote that Monroe's performance "effectively dispels once and for all the notion that she is merely a glamour personality" and Crowther proclaimed: "Hold on to your chairs, everybody, and get set for a rattling surprise. Marilyn Monroe has finally proved herself an actress."[181] She received a Golden Globe for Best Actress nomination for her performance.[91]

In August 1956, Monroe began filming MMP's first independent production, The Prince and the Showgirl, at Pinewood Studios in England.[182] It was based on Terence Rattigan's The Sleeping Prince, a play about an affair between a showgirl and a prince in the 1910s. The main roles had first been played on stage by Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh; he reprised his role and directed and co-produced the film.[168] The production was complicated by conflicts between him and Monroe.[183] He angered her with the patronizing statement "All you have to do is be sexy", and by wanting her to replicate Leigh's interpretation.[184] He also disliked the constant presence of Paula Strasberg, Monroe's acting coach, on set.[185]

In retaliation to what she considered Olivier's "condescending" behavior, Monroe started arriving late and became uncooperative, stating later that "if you don't respect your artists, they can't work well."[183] Her drug use increased and, according to Spoto, she became pregnant and miscarried during the production.[186] She also had arguments with Greene over how MMP should be run, including whether Miller should join the company.[186] Despite the difficulties, the film was completed on schedule by the end of the year.[187] It was released in June 1957 to mixed reviews, and proved unpopular with American audiences.[188] It was better received in Europe, where she was awarded the Italian David di Donatello and the French Crystal Star awards, and was nominated for a BAFTA.[189]

After returning to the United States, Monroe took an 18-month hiatus from work to concentrate on married life on the East Coast. She and Miller split their time between their apartment in New York and an eighteenth-century farmhouse they purchased in Roxbury, Connecticut, and spent the summer in Amagansett, Long Island.[190] She became pregnant in mid-1957, but it was ectopic and had to be terminated.[191] She suffered a miscarriage a year later.[192] Her gynecological problems were largely caused by endometriosis, a disease from which she suffered throughout her adult life.[193][lower-alpha 8] Monroe was also briefly hospitalized during this time due to a barbiturate overdose.[196] During the hiatus, she dismissed Greene from MMP and bought his share of the company as they could not settle their disagreements and she had begun to suspect that he was embezzling money from the company.[197]

Monroe returned to Hollywood in July 1958 to act opposite Jack Lemmon and Tony Curtis in Billy Wilder's comedy on gender roles, Some Like It Hot.[198] Although she considered the role of Sugar Kane another "dumb blonde", she accepted it due to Miller's encouragement and the offer of receiving ten percent of the film's profits in addition to her standard pay.[199] The difficulties of the film's production have since become "legendary".[200] Monroe would demand dozens of re-takes, and could not remember her lines or act as directed – Curtis famously stated that kissing her was "like kissing Hitler" due to the number of re-takes.[201] Monroe herself privately likened the production to a sinking ship and commented on her co-stars and director saying "[but] why should I worry, I have no phallic symbol to lose."[202] Many of the problems stemmed from a conflict between her and Wilder, who also had a reputation for being difficult, on how she should play the character.[203] Monroe made Wilder angry by asking him to alter many of her scenes, which in turn made her stage fright worse, and it is suggested that she deliberately ruined several scenes to act them her way.[203]

In the end, Wilder was happy with Monroe's performance, stating: "Anyone can remember lines, but it takes a real artist to come on the set and not know her lines and yet give the performance she did!"[204] Despite the difficulties of its production, when Some Like It Hot was released in March 1959, it became a critical and commercial success.[205] Monroe's performance earned her a Golden Globe for Best Actress, and prompted Variety to call her "a comedienne with that combination of sex appeal and timing that just can't be beat".[189][206] It has been voted one of the best films ever made in polls by the American Film Institute and Sight & Sound.[207][208]

Career decline and personal difficulties (1960–1962)

After Some Like It Hot, Monroe took another hiatus until late 1959, when she returned to Hollywood to star in the musical comedy Let's Make Love, about an actress and a millionaire who fall in love when performing in a satirical play.[209] She chose George Cukor to direct and Miller re-wrote portions of the script, which she considered weak; she accepted the part solely because she was behind on her contract with Fox, having only made one of four promised films.[210] Its production was delayed by her frequent absences from set.[209] She had an affair with Yves Montand, her co-star, which was widely reported by the press and used in the film's publicity campaign.[211] Let's Make Love was unsuccessful upon its release in September 1960;[212] Crowther described Monroe as appearing "rather untidy" and "lacking ... the old Monroe dynamism",[213] and Hedda Hopper called the film "the most vulgar picture she's ever done".[214] Truman Capote lobbied for her to play Holly Golightly in a film adaptation of Breakfast at Tiffany's, but the role went to Audrey Hepburn as its producers feared that Monroe would complicate the production.[215]

The last film that Monroe completed was John Huston's The Misfits, which Miller had written to provide her with a dramatic role.[216] She played Roslyn, a recently divorced woman who becomes friends with three aging cowboys, played by Clark Gable, Eli Wallach and Montgomery Clift. Its filming in the Nevada desert between July and November 1960 was again difficult.[217] Monroe and Miller's four-year marriage was effectively over, and he began a new relationship.[216] Monroe disliked that he had based her role partly on her life, and thought it inferior to the male roles; she also struggled with Miller's habit of re-writing scenes the night before filming.[218] Her health was also failing: she was in pain from gallstones, and her drug addiction was so severe that her make-up usually had to be applied while she was still asleep under the influence of barbiturates.[219] In August, filming was halted for her to spend a week detoxing in a Los Angeles hospital.[219] Despite her problems, Huston stated that when Monroe was playing Roslyn, she "was not pretending to an emotion. It was the real thing. She would go deep down within herself and find it and bring it up into consciousness."[220]

Monroe and Miller separated after filming wrapped up, and she was granted a quick divorce in Mexico in January 1961.[221] The Misfits was released the following month, failing at the box office.[222] Its reviews were mixed,[222] with Variety complaining of frequently "choppy" character development,[223] and Bosley Crowther calling Monroe "completely blank and unfathomable" and stating that "unfortunately for the film's structure, everything turns upon her".[224] Despite the film's initial failure, it has received more favorable reviews from critics and film scholars in the twenty-first century. Geoff Andrew of the British Film Institute has called it a classic,[225] Huston scholar Tony Tracy has described Monroe's performance the "most mature interpretation of her career",[226] and Geoffrey McNab of The Independent has praised her for being "extraordinary" in portraying Roslyn's "power of empathy".[227]

Monroe was next to star in a television adaptation of W. Somerset Maugham's short story Rain for NBC, but the project fell through as the network did not want to hire her choice of director, Lee Strasberg.[228] Instead of working, she spent the first six months of 1961 preoccupied by health problems, undergoing surgery for her endometriosis and a cholecystectomy, and spending four weeks in hospital care – including a brief stint in a mental ward – for depression.[229][lower-alpha 9] She was helped by her ex-husband Joe DiMaggio, with whom she now rekindled a friendship.[231] In spring 1961, Monroe also moved back to California after six years on the East Coast.[232] She dated Frank Sinatra for several months, and in early 1962 purchased a house in Brentwood, Los Angeles.[232]

Monroe returned to the public eye in spring 1962: she received a "World Film Favorite" Golden Globe award and began to shoot a new film for 20th Century-Fox, Something's Got to Give, a re-make of My Favorite Wife (1940).[233] It was to be co-produced by MMP, directed by George Cukor and to co-star Dean Martin and Cyd Charisse.[234] Days before filming began, Monroe caught sinusitis; despite medical advice to postpone the production, Fox began it as planned in late April.[235] Monroe was too ill to work for the majority of the next six weeks, but despite confirmations by multiple doctors, the studio tried to put pressure on her by alleging publicly that she was faking it.[235] On May 19, she took a break to sing "Happy Birthday" on stage at President John F. Kennedy's birthday celebration at Madison Square Garden in New York.[236] She drew attention with her costume: a beige, skintight dress covered in rhinestones, which made her appear nude.[236][lower-alpha 10] Monroe's trip to New York caused even more irritation for Fox executives, who had wanted her to cancel it.[238]

Monroe next filmed a scene for Something's Got to Give in which she swam naked in a swimming pool.[239] To generate advance publicity, the press was invited to take photographs of the scene, which were later published in Life; this was the first time that a major star had posed nude while at the height of their career.[240] When she was again on sick leave for several days, Fox decided that it could not afford to have another film running behind schedule when it was already struggling to cover the rising costs of Cleopatra (1963).[241] On June 7, Monroe was fired and sued for $750,000 in damages.[242] She was replaced by Lee Remick, but after Martin refused to make the film with anyone other than Monroe, Fox sued him as well and shut down the production.[243] The studio blamed Monroe for the film's demise and began spreading negative publicity about her, even alleging that she was mentally disturbed.[242]

Fox soon regretted its decision, and re-opened negotiations with Monroe later in June; a settlement about a new contract, including re-commencing Something's Got to Give and a starring role in the black comedy What a Way to Go! (1964), was reached later that summer.[244] To repair her public image, Monroe engaged in several publicity ventures, including interviews for Life and Cosmopolitan and her first photo shoot for Vogue.[245] For Vogue, she and photographer Bert Stern collaborated for two series of photographs, one a standard fashion editorial and another of her posing nude, which were both later published posthumously with the title The Last Sitting.[246] In the last weeks of her life, she was also planning on starring in a biopic of Jean Harlow.[247]

Death

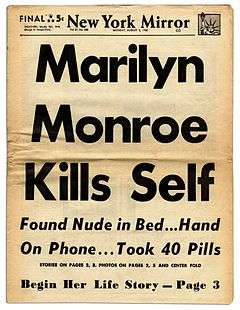

Monroe was found dead in the bedroom of her Brentwood home by her psychiatrist, Dr. Ralph Greenson, in the early morning hours of August 5, 1962. Greenson had been called there by her housekeeper Eunice Murray, who was staying overnight and had awoken at 3:00 a.m. "sensing that something was wrong". Murray had seen light from under Monroe's bedroom door, but had not been able to get a response and found the door locked.[248] The death was officially confirmed by Monroe's physician, Dr. Hyman Engelberg, who arrived at the house at around 3:50 a.m.[248] At 4:25 a.m., they notified the Los Angeles Police Department.[248]

The Los Angeles County Coroners Office was assisted in their investigation by experts from the Los Angeles Suicide Prevention Team.[249] It was estimated that Monroe had died between 8:30 and 10:30 p.m.,[250] and the toxicological analysis concluded that the cause of death was acute barbiturate poisoning, as she had 8 mg% (milligrams per 100 milliliters of solution) chloral hydrate and 4.5 mg% of pentobarbital (Nembutal) in her blood, and a further 13 mg% of pentobarbital in her liver.[251] Empty bottles containing these medicines were found next to her bed.[249] The possibility of Monroe having accidentally overdosed was ruled out as the dosages found in her body were several times over the lethal limit.[252] Her doctors stated that she had been prone to "severe fears and frequent depressions" with "abrupt and unpredictable" mood changes, and had overdosed several times in the past, possibly intentionally.[252][253] Due to these facts and the lack of any indication of foul play, her death was classified a probable suicide.[254]

Monroe's unexpected death was front-page news in the United States and Europe.[255] According to Lois Banner, "it's said that the suicide rate in Los Angeles doubled the month after she died; the circulation rate of most newspapers expanded that month",[255] and the Chicago Tribune reported that they had received hundreds of phone calls from members of the public requesting information about her death.[256] French artist Jean Cocteau commented that her death "should serve as a terrible lesson to all those, whose chief occupation consists of spying on and tormenting film stars", her former co-star Laurence Olivier deemed her "the complete victim of ballyhoo and sensation", and Bus Stop director Joshua Logan stated that she was "one of the most unappreciated people in the world".[257] Her funeral, held at the Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery on August 8, was private and attended by only her closest associates.[258] It was arranged by Joe DiMaggio and her business manager Inez Melson.[258] Hundreds of spectators crowded the streets around the cemetery.[258] Monroe was later interred at crypt No. 24 at the Corridor of Memories.[259]

Several conspiracy theories about Monroe's death have been introduced in the decades afterwards, including murder and accidental overdose.[260] The murder speculations first gained mainstream attention with the publication of Norman Mailer's Marilyn: A Biography in 1973, and in the following years became widespread enough for the Los Angeles County District Attorney John Van de Kamp to conduct a "threshold investigation" in 1982 to see whether a criminal investigation should be opened.[261] No evidence of foul play was found.[262]

Screen persona and reception

"I never quite understood it, this sex symbol. I always thought symbols were those things you clash together! That's the trouble, a sex symbol becomes a thing. I just hate to be a thing. But if I'm going to be a symbol of something I'd rather have it sex than some other things they've got symbols of."[263]

—Monroe in an interview for Life in 1962

When beginning to develop her star image, 20th Century-Fox wanted Monroe to replace the aging Betty Grable, their most popular "blonde bombshell" of the 1940s.[264] While the 1940s had been the heyday of actresses perceived as tough and smart, such as Katharine Hepburn and Barbara Stanwyck, who appealed to women-dominated audiences, the studio wanted Monroe to be a star of the new decade that would draw men to movie theaters.[264] She played a significant part in the creation of her public image from the beginning, and towards the end of her career exerted almost full control over it.[265][266] Monroe devised many of her publicity strategies, cultivated friendships with gossip columnists such as Sidney Skolsky and Louella Parsons, and controlled the use of her images.[267] Besides Grable, she was often compared to another iconic blonde, 1930s film star Jean Harlow.[268] The comparison was partly prompted by Monroe, who named Harlow as her childhood idol, wanted to play her in a biopic, and even employed Harlow's hair stylist to color her hair.[269]

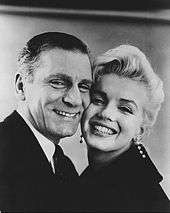

.jpg)

Monroe's screen persona centered on her blonde hair, and the stereotypes associated with it, especially dumbness, naïveté, sexual availability and artificiality.[270] She often used a breathy, childish voice in her films, and in interviews gave the impression that everything she said was "utterly innocent and uncalculated", parodying herself with double entendres that came to be known as "Monroeisms".[271] For example, when she was asked what she had on in the 1949 nude photo shoot, she replied, "I had the radio on".[272] Having begun her career as a pin-up model, Monroe's hourglass figure was one of her most often noted features.[273] Film scholar Richard Dyer has written that Monroe was often positioned so that her curvy silhouette was on display, and in her publicity photos often posed like a pin-up.[273] Her distinctive, hip-swinging walk also drew attention to her body, earning her the nickname "the girl with the horizontal walk".[106]

Clothing played an important part in Monroe's star image. She often wore white to emphasize her blondness, and drew attention by wearing revealing outfits that showed off her figure.[274] Her publicity stunts often revolved around her clothing exposing large amounts of her body or even malfunctioning, such as when one of the shoulder straps of her dress suddenly snapped during a press conference.[275] In press stories, Monroe was portrayed as the embodiment of the American Dream, as a girl who had risen from a miserable childhood to Hollywood stardom.[276] Stories of her time spent in foster families and an orphanage were exaggerated and even partly fabricated in her studio biographies.[277]

Although Monroe's screen persona as a dim-witted but sexually attractive blonde was a carefully crafted act, audiences and film critics believed it to be her real personality and that she was not acting in her comedies. This became an obstacle in her later career, when she wanted to change her public image and pursue other kinds of roles, or to be respected as a businesswoman.[278] Academic Sarah Churchwell, who has studied narratives about Monroe, has stated:

The biggest myth is that she was dumb. The second is that she was fragile. The third is that she couldn't act. She was far from dumb, although she was not formally educated, and she was very sensitive about that. But she was very smart indeed – and very tough. She had to be both to beat the Hollywood studio system in the 1950s. [...] The dumb blonde was a role – she was an actress, for heaven's sake! Such a good actress that no one now believes she was anything but what she portrayed on screen.[279]

Lois Banner has written that she often subtly parodied her status as a sex symbol in her films and public appearances.[280] Monroe stated that she was influenced by Mae West, saying that she "learned a few tricks from her – that impression of laughing at, or mocking, her own sexuality".[281] In the 1950s, she also studied comedy in classes given by mime and dancer Lotte Goslar, famous for her comic stage performances, and had her accompany her on film sets to instruct her.[282] In Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, one of the films in which she played an archetypal dumb blonde, Monroe had the sentence "I can be smart when it's important, but most men don't like it" added to her character's lines in the script.[283]

Dyer has stated Monroe's star image was created mainly for the male gaze and that she usually played "the girl", who is defined solely by her gender, in her films.[284] Her roles were almost always chorus girls, secretaries, or models; occupations where "the woman is on show, there for the pleasure of men."[284] Film scholar Thomas Harris, who analyzed Monroe's public image in 1957, wrote that her working class roots and lack of family made her appear more sexually available, "the ideal playmate", in contrast to her contemporary Grace Kelly, who was also marketed as an attractive blonde, but due to her upper-class background came to be seen as a sophisticated actress, unattainable for the majority of male viewers.[285]

According to Dyer, Monroe became "virtually a household name for sex" in the 1950s and "her image has to be situated in the flux of ideas about morality and sexuality that characterised the fifties in America", such as Freudian ideas about sex, the Kinsey report (1953), and Betty Friedan's The Feminine Mystique (1963).[286] By appearing vulnerable and unaware of her sex appeal, Monroe was the first sex symbol to present sex as natural and without danger, in contrast to the 1940s femme fatales.[287] Spoto likewise describes her as the embodiment of "the postwar ideal of the American girl, soft, transparently needy, worshipful of men, naïve, offering sex without demands", which is echoed in Molly Haskell's statement that "she was the fifties fiction, the lie that a woman had no sexual needs, that she is there to cater to, or enhance, a man's needs."[288] Monroe's contemporary Norman Mailer wrote that "Marilyn suggested sex might be difficult and dangerous with others, but ice cream with her", while Groucho Marx characterized her as "Mae West, Theda Bara, and Bo Peep all rolled into one".[289] According to Haskell, due to her status as a sex symbol, Monroe was less popular with women than with men, as they "couldn't identify with her and didn't support her", although this would change after her death.[290]

Dyer has also argued that platinum blonde hair became such a defining feature of Monroe because it made her "racially unambiguous" and exclusively white just as the Civil Rights Movement was beginning, and that she should be seen as emblematic of racism in twentieth-century popular culture.[291] Banner agrees that it may not be a coincidence that Monroe launched a trend of platinum blonde actresses during the Civil Rights Movement, but has also criticized Dyer, pointing out that in her highly publicized private life Monroe associated with people who were seen as "white ethnics", such as Joe DiMaggio (Italian-American) and Arthur Miller (Jewish).[292] According to Banner, she sometimes challenged prevailing racial norms in her publicity photographs; for example, in an image featured in Look in 1951, she was shown in revealing clothes while practicing with African-American singing coach Phil Moore.[293]

Monroe was perceived as a specifically American star, "a national institution as well known as hot dogs, apple pie, or baseball" according to Photoplay.[294] Banner calls her the symbol of populuxe, a star whose joyful and glamorous public image "helped the nation cope with its paranoia in the 1950s about the Cold War, the atom bomb, and the totalitarian communist Soviet Union".[295] Historian Fiona Handyside writes that the French female audiences associated whiteness/blondness with American modernity and cleanliness, and so Monroe came to symbolize a modern, "liberated" woman whose life takes place in the public sphere.[296] Film historian Laura Mulvey has written of her as an endorsement for American consumer culture:

If America was to export the democracy of glamour into post-war, impoverished Europe, the movies could be its shop window ... Marilyn Monroe, with her all American attributes and streamlined sexuality, came to epitomise in a single image this complex interface of the economic, the political, and the erotic. By the mid 1950s, she stood for a brand of classless glamour, available to anyone using American cosmetics, nylons and peroxide.[297]

To profit from Monroe's popularity, 20th Century-Fox cultivated several lookalike actresses, including Jayne Mansfield and Sheree North.[298] Other studios also attempted to create their own Monroes: Universal Pictures with Mamie Van Doren,[299] Columbia Pictures with Kim Novak,[300] and Rank Organisation with Diana Dors.[301]

Legacy

According to The Guide to United States Popular Culture, "as an icon of American popular culture, Monroe's few rivals in popularity include Elvis Presley and Mickey Mouse ... no other star has ever inspired such a wide range of emotions – from lust to pity, from envy to remorse."[302] Art historian Gail Levin has stated that Monroe may have been "the most photographed person of the 20th century",[303] and The American Film Institute has named her the sixth greatest female screen legend in American film history. The Smithsonian Institution has included her on their list of "100 Most Significant Americans of All Time",[304] and both Variety and VH1 have placed her in the top ten in their rankings of the greatest popular culture icons of the twentieth century.[305][306] Hundreds of books have been written about Monroe, she has been the subject of films, plays, operas, and songs, and has influenced artists and entertainers such as Andy Warhol and Madonna.[307][308] She also remains a valuable brand:[309] her image and name have been licensed for hundreds of products, and she has been featured in advertising for multinational corporations and brands such as Max Factor, Chanel, Mercedes-Benz, and Absolut Vodka.[310][311]

Monroe's enduring popularity is linked to her conflicted public image.[312] On the one hand, she remains a sex symbol, beauty icon and one of the most famous stars of classical Hollywood cinema.[313][314][315] On the other, she is also remembered for her troubled private life, unstable childhood, struggle for professional respect, and her death and the conspiracy theories surrounding it.[316] She has been written about by scholars and journalists interested in gender and feminism,[317] such as Gloria Steinem, Jacqueline Rose,[318] Molly Haskell,[319] Sarah Churchwell,[311] and Lois Banner.[320] Some, such as Steinem, have viewed her as a victim of the studio system.[317][321] Others, such as Haskell,[322] Rose,[318] and Churchwell,[311] have instead stressed Monroe's proactive role in her career and her participation in the creation of her public persona.

Due to the contrast between her stardom and troubled private life, Monroe is closely linked to broader discussions about modern phenomena such as mass media, fame, and consumer culture.[323] According to academic Susanne Hamscha, because of her continued relevance to ongoing discussions about modern society, Monroe is "never completely situated in one time or place" but has become "a surface on which narratives of American culture can be (re-)constructed", and "functions as a cultural type that can be reproduced, transformed, translated into new contexts, and enacted by other people".[323] Similarly, Banner has called Monroe the "eternal shapeshifter" who is re-created by "each generation, even each individual ... to their own specifications".[324]

While Monroe remains a cultural icon, critics are divided on her legacy as an actress. David Thomson called her body of work "insubstantial"[325] and Pauline Kael wrote that she could not act, but rather "used her lack of an actress's skills to amuse the public. She had the wit or crassness or desperation to turn cheesecake into acting – and vice versa; she did what others had the 'good taste' not to do".[326] In contrast, according to Peter Bradshaw, Monroe was a talented comedian who "understood how comedy achieved its effects",[327] and Roger Ebert wrote that "Monroe's eccentricities and neuroses on sets became notorious, but studios put up with her long after any other actress would have been blackballed because what they got back on the screen was magical".[328] Similarly, Jonathan Rosenbaum stated that "she subtly subverted the sexist content of her material" and that "the difficulty some people have discerning Monroe's intelligence as an actress seems rooted in the ideology of a repressive era, when superfeminine women weren't supposed to be smart".[329]

Filmography

- Dangerous Years (1947)

- Scudda Hoo! Scudda Hay! (1948)

- Ladies of the Chorus (1948)

- Love Happy (1949)

- A Ticket to Tomahawk (1950)

- The Asphalt Jungle (1950)

- All About Eve (1950)

- The Fireball (1950)

- Right Cross (1951)

- Home Town Story (1951)

- As Young as You Feel (1951)

- Love Nest (1951)

- Let's Make It Legal (1951)

- Clash by Night (1952)

- We're Not Married! (1952)

- Don't Bother to Knock (1952)

- Monkey Business (1952)

- O. Henry's Full House (1952)

- Niagara (1953)

- Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953)

- How to Marry a Millionaire (1953)

- River of No Return (1954)

- There's No Business Like Show Business (1954)

- The Seven Year Itch (1955)

- Bus Stop (1956)

- The Prince and the Showgirl (1957)

- Some Like It Hot (1959)

- Let's Make Love (1960)

- The Misfits (1961)

- Something's Got to Give (1962)

Notes

- ↑ Gladys named Mortensen as Monroe's father in the birth certificate (although the name was misspelled),[11] but it is unlikely that he was the father.[12] Biographers Fred Guiles and Lois Banner have stated that her father was most likely Charles Stanley Gifford, a co-worker with whom Gladys had an affair in 1925, whereas Donald Spoto thinks another co-worker was most likely the father.[13]

- ↑ Monroe spoke about being sexually abused by a lodger when she was eight years old to her biographers Ben Hecht in 1953–54 and Maurice Zolotow in 1960, and in interviews for Paris Match and Cosmopolitan.[25] Although she refused to name the abuser, Banner believes he was George Atkinson, as he was a lodger and fostered Monroe when she was eight; Banner also states that Monroe's description of the abuser fits other descriptions of Atkinson.[26] Banner has argued that the abuse may have been a major causative factor in Monroe's mental health problems, and has also written that as the subject was taboo in mid-century United States, Monroe was unusual in daring to speak about it publicly.[27] Spoto does not mention the incident but states that Monroe was sexually abused by Grace's husband in 1937 and by a cousin while living with a relative in 1938.[28] Barbara Leaming repeats Monroe's account of the abuse, but earlier biographers Fred Guiles, Anthony Summers and Carl Rollyson have doubted the incident due to lack of evidence beyond Monroe's statements.[29]

- ↑ RKO's owner Howard Hughes had expressed an interest in Monroe after seeing her on a magazine cover.[56]

- ↑ It has sometimes been erroneously claimed that Monroe appeared as an extra in other Fox films during this period, including Green Grass of Wyoming, The Shocking Miss Pilgrim, and You Were Meant For Me, but there is no evidence to support this.[63]

- ↑ Monroe and Greene had first met and had a brief affair in 1949, and met again in 1953, when he photographed her for Look. She told him about her grievances with the studio, and Greene suggested that they start their own production company.[150]

- ↑ Monroe underwent psychoanalysis regularly from 1955 until her death in 1962. Her analysts were psychiatrists Margaret Hohenberg (1955–57), Anna Freud (1957), Marianne Kris (1957–61), and Ralph Greenson (1960–62).[160]

- ↑ Monroe identified with the Jewish people as a "dispossessed group" and wanted to convert to make herself part of Miller's family.[174] She was instructed by Rabbi Robert Goldberg and converted on July 1, 1956.[173] Monroe's interest in Judaism as a religion was limited: she referred to herself as a "Jewish atheist" and after her divorce from Miller, did not practice the faith aside from retaining some religious items.[173] Egypt also lifted her ban after the divorce was finalized in 1961.[173]

- ↑ It also caused her to experience severe menstrual pain throughout her life, necessitating a clause in her contract allowing her to be absent from work during her period, and required several surgeries.[193] It has sometimes been alleged that Monroe underwent several abortions, and that unsafe abortions made by persons without proper medical training would have contributed to her inability to maintain a pregnancy.[194] The abortion rumors began from statements made by Amy Greene, the wife of Milton Greene, but have not been confirmed by any concrete evidence.[195] Furthermore, Monroe's autopsy report did not note any evidence of abortions.[195]

- ↑ Monroe first admitted herself to the Payne Whitney Psychiatric Clinic in New York, at the suggestion of her psychiatrist Marianne Kris.[230] Kris later stated that her choice of hospital was a mistake: Monroe was placed on a ward meant for severely mentally ill people with psychosis, where she was locked in a padded cell and was not allowed to move to a more suitable ward or to leave the hospital.[230] Monroe was finally able to leave the hospital after three days with the help of Joe DiMaggio, and moved to the Columbia University Medical Center, spending a further 23 days there.[230]

- ↑ Monroe and Kennedy had mutual friends and were familiar with each other. Although they sometimes had casual sexual encounters, there is no evidence that their relationship was serious.[237]

References

- ↑ Hertel, Howard; Heff, Don (August 6, 1962). "Marilyn Monroe Dies; Pills Blamed". Los Angeles Times. Tribune Publishing. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- ↑ Chapman 2001, pp. 542–543; Hall 2006, p. 468.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 3, 13–14; Banner 2012, p. 13.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 9–10; Rollyson 2014, pp. 26–29.

- ↑ Miracle & Miracle 1994, p. see family tree.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 7–9; Banner 2012, p. 19.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 7–9.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, p. 88, for first meeting in 1944; Banner 2012, p. 72, for mother telling Monroe of sister in 1938.

- ↑ Churchwell 2004, p. 150, citing Spoto and Summers; Banner 2012, pp. 24–25.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 17, 57.

- ↑ Churchwell 2004, p. 150, citing Spoto, Summers and Guiles.

- ↑ Churchwell 2004, pp. 149–152; Banner 2012, p. 26; Spoto 2001, p. 13.

- ↑ Churchwell 2004, p. 152; Banner 2012, p. 26; Spoto 2001, p. 13.

- 1 2 3 Spoto 2001, pp. 17–26; Banner 2012, pp. 32–35.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 16–17; Churchwell 2004, p. 164; Banner 2012, pp. 22–32.

- ↑ Banner 2012, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Banner 2012.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 26–28; Banner 2012, pp. 35–39.

- ↑ Churchwell 2004, pp. 155–156.

- ↑ Churchwell 2004, pp. 155–156; Banner 2012, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 100–101, 106–107, 215–216; Banner 2012, pp. 39–42, 45–47, 62, 72, 91, 205.

- ↑ Meryman, Richard (September 14, 2007). "Great interviews of the 20th century: "When you're famous you run into human nature in a raw kind of way"". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 40–49; Churchwell 2004, p. 165; Banner 2012, pp. 40–62.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 33–40; Banner 2012, pp. 40–54.

- ↑ Banner 2012, pp. 48–49.

- ↑ Banner 2012, pp. 40–59.

- ↑ Banner 2012, pp. 7, 40–59.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, p. 55; Churchwell 2004, pp. 166–173.

- ↑ Churchwell 2004, pp. 166–173.

- ↑ Banner 2012, pp. 27, 54–73.

- ↑ Banner 2012, pp. 47–48.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 44–45; Churchwell 2004, pp. 165–166; Banner 2012, pp. 62–63.

- ↑ Banner 2012, pp. 60-63.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 49–50; Banner 2012, pp. 62–63 (see also footnotes), 455.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 49–50; Banner 2012, pp. 62–63, 455.

- ↑ Banner 2012, pp. 62–64.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 51–67; Banner 2012, pp. 62–86.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 68–69; Banner 2012, p. 75–77.

- ↑ Banner 2012, pp. 73–76.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 67–69; Banner 2012, p. 86.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 67–69.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 70–75; Banner 2012, pp. 86–90.

- ↑ Banner 2012, pp. 86–90.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 70–75.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, p. 70–78.

- 1 2 3 Spoto 2001, pp. 83–86; Banner 2012, pp. 91–98.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 90–91; Churchwell 2004, p. 176.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 90–93; Churchwell 2004, pp. 176–177.

- ↑ "YANK USA 1945". Wartime Press. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ↑ Banner 2012, pp. 103–104.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 93–95; Banner 2012, pp. 105–108.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 95–107.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, p. 95, for statement & covers; Banner 2012, p. 109, for Snively's statement.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 110–111.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 110–112; Banner 2012, pp. 117–119.

- ↑ Banner 2012, p. 119.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 112–114.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, p. 114.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, p. 109.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 118–119.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 119–120; Banner 2012, pp. 130–131.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 120–121.

- 1 2 Churchwell 2004, p. 59.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 122–126.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 120–121, 126; Banner 2012, p. 133.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 122–129; Banner 2012, p. 133.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 130–133; Banner 2012, pp. 133–144.

- ↑ Churchwell 2004, pp. 204–216, citing Summers, Spoto and Guiles for Schenck; Banner 2012, pp. 141–144; Spoto 2001, pp. 133–134.

- ↑ Banner 2012, p. 139.

- 1 2 Spoto 2001, pp. 133–134.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 141–144.

- ↑ Banner 2012, p. 148.

- ↑ Summers 1985, p. 43.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 145–146; Banner 2012, pp. 149, 157.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, p. 146; Banner 2012, pp. 148–149.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 151–153.

- ↑ Banner 2012, p. 149.

- ↑ Churchwell 2004, pp. 59–60.

- 1 2 Spoto 2001, pp. 159–162.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 168–170.

- ↑ Riese & Hitchens 1988, p. 228; Spoto 2001, p. 182.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 175–177; Banner 2012, p. 157.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 183, 191.

- ↑ Churchwell 2004, p. 60.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 179–187; Churchwell 2004, p. 60.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 188–189; Banner 2012, pp. 170–171.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, p. 192.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 180–181; Banner 2012, pp. 163–167, 181–182 for Kazan and others.

- ↑ Muir, Florabel (October 19, 1952). "Marilyn Monroe Tells: How to Deal With Wolves". Chicago Tribune. Tribune Publishing. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ↑ Hopper, Hedda (May 4, 1952). "They Call Her The Blowtorch Blonde". Chicago Tribune. Tribune Publishing. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- 1 2 Kahana, Yoram (January 30, 2014). "Marilyn: The Globes' Golden Girl". Hollywood Foreign Press Association (HFPA). Retrieved September 11, 2015.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, p. 201; Banner 2012, p. 192.

- ↑ Summers 1985, p. 58; Spoto 2001, pp. 210–213.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 210–213; Churchwell 2004, pp. 224–226; Banner 2012, pp. 194–195.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 210–213; Churchwell 2004, pp. 61–62, 224–226; Banner 2012, pp. 194–195.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 224–225.

- ↑ Churchwell 2004, p. 61 for being commercially successful; Banner 2012, p. 178 for wishes to not be solely a sex symbol.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 194–195; Churchwell 2004, pp. 60–61.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 194–195.

- ↑ "Clash By Night". American Film Institute. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 196–197.

- ↑ Crowther, Bosley (July 19, 1952). "Don't Bother to Knock". The New York Times. Arthur Ochs Sulzberger, Jr. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ↑ Churchwell 2004, p. 61; Banner 2012, p. 180.

- ↑ "Review: Don't Bother to Knock". Variety. Penske Media Corporation. December 31, 1951. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, p. 200.

- 1 2 3 Churchwell 2004, p. 62.

- ↑ Churchwell 2004, p. 238.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, p. 139, 195, 233–234, 241, 244, 372.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 328–329; Churchwell 2004, pp. 51–56; 238; Banner 2012, pp. , 188–189; 211–214.

- ↑ "Filmmaker Interview — Gail Levin". PBS. July 19, 2006. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 328–329; Churchwell 2004, p. 238; Banner 2012, pp. 211–214, 311.

- ↑ Churchwell 2004, pp. 257–264.

- ↑ Banner 2012, pp. 189–190, 210-211.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, p. 221; Churchwell 2004, pp. 61–65; Lev 2013, p. 168.

- 1 2 "The 2006 Motion Picture Almanac, Top Ten Money Making Stars". Quigley Publishing Company. Archived from the original on December 21, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2008.

- ↑ Churchwell 2004, p. 233.

- ↑ Churchwell 2004, pp. 25, 62.

- 1 2 Churchwell 2004, p. 62; Banner 2012, pp. 195–196.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, p. 221; Banner 2012, p. 205; Leaming 1998, p. 75 on box office figure.

- ↑ "Niagara Falls Vies With Marilyn Monroe". The New York Times. Arthur Ochs Sulzberger, Jr. January 22, 1953. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ↑ "Review: 'Niagara'". Variety. Penske Media Corporation. December 31, 1952. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- 1 2 Spoto 2001, pp. 236–238; Churchwell 2004, p. 234; Banner 2012, pp. 205–206.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, p. 231; Churchwell 2004, p. 64; Banner 2012, p. 200; Leaming 1998, pp. 75–76.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 219–220; Banner 2012, p. 177.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, p. 242; Banner 2012, pp. 208–209.

- ↑ Solomon 1988, p. 89; Churchwell 2004, p. 63.

- ↑ Brogdon, William (July 1, 1953). "Gentlemen Prefer Blondes". Variety. Penske Media Corporation. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ↑ Crowther, Bosley (July 16, 1953). "Gentlemen Prefer Blondes". The New York Times. Arthur Ochs Sulzberger, Jr. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, p. 250.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, p. 238; Churchwell 2004, pp. 64–65.

- ↑ Solomon 1988, p. 89; Churchwell 2004, p. 65; Lev 2013, p. 209.

- ↑ Solomon 1988, p. 89.

- 1 2 Churchwell 2004, p. 217.

- ↑ Churchwell 2004, p. 68.

- ↑ Churchwell 2004, pp. 68, 208–209.

- ↑ Summers 1985, p. 92; Spoto 2001, p. 254–259.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, p. 260.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 262–263.

- ↑ Churchwell 2004, p. 241.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, p. 267.

- 1 2 Spoto 2001, p. 271.

- ↑ Churchwell 2004, pp. 66–67.

- ↑ Riese & Hitchens 1988, pp. 338–440; Spoto 2001, p. 277; Churchwell 2004, p. 66; Banner 2012, p. 227.

- 1 2 Spoto 2001, pp. 283–284.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 284–285; Banner 2012, pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 208, 222–223; 262–267, 292; Churchwell 2004, pp. 243–245; Banner 2012, pp. 204; 219–221.

- ↑ Summers 1985, pp. 103–105; Spoto 2001, pp. 290–295; Banner 2012, pp. 224–225.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, p. 331.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 295–298; Churchwell 2004, p. 246.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 158–159, 252–254.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, p. 303.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 302–303.

- 1 2 Spoto 2001, pp. 301–302.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, p. 338.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, p. 302.

- ↑ Monroe 2010, pp. 78-81.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, p. 327.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, p. 350.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 310–313.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 312–313, 375, 384–385, 421, 459 on years and names.

- 1 2 Spoto 2001; Churchwell 2004, p. 253, for Miller; Banner 2012, p. 285, for Brando.

- 1 2 Spoto 2001, p. 337; Meyers 2010, p. 98.

- ↑ Summers 1985, p. 157; Spoto 2001, pp. 318–320; Churchwell 2004, pp. 253–254.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 336–345.

- ↑ Summers 1985, p. 157; Churchwell 2004, pp. 253–254.

- 1 2 3 Spoto 2001, pp. 339–340.

- 1 2 Banner 2012, pp. 296–297.

- 1 2 Spoto 2001, p. 341.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, p. 345.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 343–345.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 364–365.

- ↑ Schreck, Tom (November 2014). "Marilyn Monroe's Westchester Wedding; Plus, More County Questions And Answers". Westchester Magazine.

- 1 2 3 4 Meyers 2010, pp. 156–157.

- ↑ Banner 2012, p. 256.

- ↑ Churchwell 2004, pp. 253–257; Meyers 2010, p. 155.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 352–357.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 352–354.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 354–358, for location and time; Banner 2012, p. 297, 310.

- ↑ Banner 2012, p. 254.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 358–359; Churchwell 2004, p. 69.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, p. 358.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, p. 372.

- 1 2 Churchwell 2004, pp. 258–261.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 370–379; Churchwell 2004, pp. 258–261; Banner 2012, pp. 310–311.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 370–379.

- 1 2 Spoto 2001, pp. 368–376; Banner 2012, pp. 310–314.

- ↑ Churchwell 2004, p. 69; Banner 2012, p. 314, for being on time.

- ↑ Churchwell 2004, p. 69.

- 1 2 Banner 2012, p. 346.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 381–382.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 392–393.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 406–407.

- 1 2 Churchwell 2004, pp. 274–277.

- ↑ Churchwell 2004, pp. 271–274; Banner 2012, pp. 222, 226, 329–30, 335, 362.

- 1 2 Churchwell 2004, pp. 271–274.

- ↑ Banner 2012, p. 321.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 389–391.

- ↑ Banner 2012, p. 325 on it being a comedy on gender.

- ↑ Banner 2012, p. 325.

- ↑ Churchwell 2004, p. 626.

- ↑ Spoto 2001, pp. 399–407; Churchwell 2004, p. 262.