Russian-American Company

Russian-American Company flag, 1806 design | |

Native name | Под высочайшим Его Императорского Величества покровительством Российская-Американская Компания |

|---|---|

| Joint-stock company | |

| Industry | fur trade |

| Fate | Alaska Purchase (1867) |

| Successor | Alaska Commercial Company |

| Founded | 8 July 1799[1] Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Founder | Nikolay Rezanov, Grigory Shelikhov |

| Defunct | 1881 |

| Headquarters | Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire |

Key people | Alexander Andreyevich Baranov |

The "Russian-American Company Under the Supreme Patronage of His Imperial Majesty" (Russian: Под высочайшим Его Императорского Величества покровительством Российская-Американская Компания Pod vysochayshim Yego Imperatorskogo Velichestva porkrovitelstvom Rossiyskaya-Amerikanskaya Kompaniya) was a state-sponsored chartered company formed largely on the basis of the United American Company. The company was chartered by Tsar Paul I in the Ukase of 1799,[1][2] and was mainly expected to establish new settlements in Russian America and carry out an expanded colonization program.

It was Russia's first joint-stock company, and came under the direct authority of the Ministry of Commerce of Imperial Russia. The Minister of Commerce (later, Minister of Foreign Affairs) Nikolai Petrovich Rumyantsev was a pivotal influence upon the early Company's affairs. In 1801, the company's headquarters were moved from Irkutsk to Saint Petersburg and the merchants who were initially the major stockholders were soon replaced by Russia's nobility and aristocracy. Count Rumyantsev funded Russia's first naval circumnavigation under the joint command of Adam Johann von Krusenstern and Nikolai Rezanov in 1803-1806, and later funded and directed the voyage of the Ryurik's circumnavigation of 1814–1816, which provided substantial scientific information on Alaska's and California's flora and fauna, and important ethnographic information on Alaskan and Californian (among others) natives. Bodega Bay, California was initially named "Rumyantsev Bay" (Залив Румянцев) was named in his honour during the Russian-California period (1812–1842) of Fort Ross.

Early history

The Russian government appointed an official with the title correspondent to maintain oversight of company affairs, the first being Nikolai Rezanov.[3] This role was soon expanded to a three-seat board of directors, with two elected by the stockholders and one appointed by the government.[3][4] Additionally the directors had to send reports of the company's activities directly to the tsar.[3][4] Directly administering the forts, trade stations and outposts from Pavlovskaya and later New Archangel was the Chief Manager. Alexander Andreyevich Baranov was the first chief manager, founding both New Archangel and Pavlovskaya. With the end of his service in 1818, the position was then continuously given to appointees of the Imperial Russian Navy.[4]

The Ukase of 1799 (edict or proclamation) granted the company a monopoly over trade in Russian America, defined with a southern border of 55° N latitude. Tsar Alexander I in the Ukase of 1821 asserted its domain to 45°50′ N latitude, revised by 1822 to 51° N latitude.[5] This border was challenged by the British and the United States, which ultimately resulted in the Russo-American Treaty of 1824 and the Russo-British Treaty of 1825 which established 54°40′ as the ostensible southward limit of Russian interests.[6] The only attempt at enforcement of the ukase of 1821 was the seizure of the U.S. brig Pearl in 1822, by the Russian sloop Apollon. The Pearl, a vessel of the maritime fur trade, was sailing from Boston to Sitka. On a protest from the U.S. government, the vessel was released and compensation paid.[7] A later lease to the Hudson's Bay Company of the southeastern sector of what is now the Alaska Panhandle, as far north as 56° 30' N, followed in 1838 as part of a damages settlement due to treaty violations by the company's governor, Baron Ferdinand von Wrangel, in 1833.

Under Baranov, who governed the region between 1790 and 1818, a permanent settlement was established in 1804 at "Novo-Arkhangelsk" (New Archangel, today's Sitka, Alaska), and a thriving maritime trade was organized. Alutiiq and Aleut men from the Kodiak and the Aleutian Islands were forcibly conscripted to work for the company in three year periods because they were "among the most sophisticated and effective sea otter hunters in the world."[4] During its initial years, the company had problems in maintain a pool of skilled crewmen for its ships. The limited number of Russian men proficient in naval craft in the Empire usually sought employment in the Imperial Russian Navy. Recruits for naval training by the company were sparse, in part due to the continued practise of serfdom in the Empire.[3] The Imperial government announced in 1802 for the Imperial Navy to send officers for employment in the RAC, half of their pay to come from the company.[3]

Russian merchants were restricted from the port of Guangzhou and its valuable markets, something the RAC endeavoured to change after its creation. The company funded a circumnavigation that lasted from 1803 to 1806 with the goals of expanding Russian navigational knowledge, supply the RAC stations and to open commercial relations with the Qing Empire.[8] While the expedition was able to sell its wares at the Chinese port, "no noticeable progress" towards securing Russian trading rights was made in the next half century.[8] Due to the closed Chinese ports, furs collected by the RAC had to be shipped to the Russian port of Okhotsk. From there caravans typically spent over a year traveling to Ayan, Irkutsk and the Siberian Route.[9] The majority of the pelts were traded in Kyakhta, where Chinese trade goods, principally cotton,[10] porcelain and tea, were traded for.[9]

Fort Elizabeth was built in Hawaii by Georg Anton Schäffer, an agent of the company. His actions attempt to overthrow the Kingdom of Hawaii is known as the Schäffer affair.

American merchants

Over the course the RAC's first decade of enterprise, its officials became increasingly concerned about American ships trading in adjacent coastal regions, especially their sale of firearms to natives. Throughout 1808 to 1810 entreaties to ban the trade were sent to the United States by Imperial officials, though no action was taken by the American government. Discussions were held with American ambassador John Quincy Adams in 1810 to determine the southern limits of the Russian's claimed land.[11] Government agents of the Russian Empire "claimed the whole coast of America on the Pacific, and the adjacent islands, from Bering's Strait southward toward and beyond the mouth of the Columbia River".[11] The pronouncement stalled attempts at settling a southern border of Russian America for over a decade.

John Jacob Astor sent a ship in 1810 with the intention of supplying New Archangel. The supplies were welcomed by Baranov, and the ship was hired to ship furs to Guangzhou.[12]:77–80 Upon learning of the pressing issue of American sales of firearms, Astor conceived of plan beneficial to both his American Fur Company and the RAC. In return for a monopoly to supply Russian stations through his subsidiary Pacific Fur Company and the right to transport RAC furs to the Qing Empire, Astor promised to refrain from selling firearms to Alaskan natives. The Russian Minister to the United States, Count Fyodor Palen, was inviting of the proposal. He contacted the Imperial government, noting that the deal would likely be more effective at ending the firearm sales than through diplomatic channels with the United States.[10] Astor's son-in-law, Adrian B. Bentzon, was sent to Saint Petersburg to negotiate with company and government officials in 1811.

The considered agreement was favorably received by the board of directors, outside one contentious clause. Astor requested to be allowed to transport a minor amount of furs into Russia import free, a prevailing only enjoyed by the RAC.[10] Shareholders of the company like the minister of both the Foreign and Commercial offices, Count Nikolay Rumyantsev, was vocally against the provision. He felt that Astor's primary intention of the negotiations was to secure this right.[10] Eventually the Americans dropped the provision and on 2 May 1812 a four-year agreement was signed. The two companies agreed to cease trading with other merchants and prevent the trading operations on the coast by their competitors. The onset of the War of 1812 and the capture of Astoria by the North West Company ended Astor's operations on the Pacific coast.[10]

Outside Russian America

The Russian-American Company grew interests in other parts of North America, principally Alta California, with smaller focus on Baja California and the Oregon Country. Additionally some efforts were spent on increasing relations with the Kingdom of Hawaii, with the Schäffer affair being an attempt at colonising the islands by a company agent acting alone.

Lower Pacific Northwest

Juno

While sailing south from Russian America for Alta California, the crew of the Juno attempted entering the Columbia River. Grigory Langsdorff reported that "Count Rezanov had already formed his plans for the removal of the Russian settlement [New Archangel] to the river Columbia, and was now planning to build a shipyard there."[13] The company directors were previously advised by Rezanov to establish a company settlement on the river, in a plan aiming for company expansion south "to include the coast of California in the Russian possession."[14] Bad weather made passing the mouth of the Columbia too difficult to pursue.

Saint Nikolai expedition

A company vessel, the Nikolai, was dispatched to the Oregon Country by Chief Manager Baranov in November 1808 with instructions to "if possible discover a site for a permanent Russian post in the Oregon Country."[15] On 1 November,[16] a weather system of strong gales and large waves marooned the ship on a beach north of the Quillayute River and James Island.[15] Conflict arose with the neighboring Hoh nation and the crew had to flee into the interior of the Olympic Peninsula. Clashes with the indigenous population continued over the next year, the Russians having to resort to raiding villages for food.[17] Eventually most of the crew became willing slaves to the Makah on the understanding they would be released when the next European vessel would arrive.[18] American Captain Brown of the Lydia purchased the Nikolai crew and they sailed for New Archangel, arriving there on 9 June.[19] During their time marooned on the Olympic Peninsula, seven of the crew died, including expedition commander Nikolai Bulygin and his 18-year-old wife, Anna Bulyagina.[19]

Californias

The first ship to trap furs in either Alta or Baja California for the RAC was in 1803. An American vessel owned by James O'Cain, the O'Cain, was contracted to trap sea otters on the Baja California peninsula, with half of the furs caught property of the RAC.[20] On board the ship besides its American crew were 2 RAC staff and 40 natives, principally Aleuts,[20] along with some Alutiiq of Kodiak Island.[21] The hunting equipment used in the expedition was of indigenous origin, including the notable iqyax boats. Based out of San Quintín, Alaskan natives caught sea otters from Misión de El Rosario de Abajo to Santo Domingo (located in the modern Comondú Municipality).[21] Returning Kodiak island in June 1804, the O'Cain contained a total of 1,800 sea otter skins caught by the natives or purchased from Spanish.[21] Under similar terms other American captains were employed over the years, with Aleuts continually used to trap California Sea otters, specific operations employing upwards of 300.[10] During the period between 1805 and 1812 Baranov supplied Aleut laborers to 10 American ships sent to California, with over 22,000 pelts gathered.[20]

In Aug. 1805, Nikolai Rezanov arrived at New Archangel, then visiting the scattered RAC possessions. Provisions were at the time sorely needed by the RAC posts to feed its workforce, an issue that would plague the company for decades. After Rezanov purchased the Juno, an American ship, he and its crew departed from New Archangel in February 1806 south to attempt purchasing supplies in Alta California.[12]:51–55,59 Upon entering the Californias, Rezanov negotiated with Spanish authorities in the name of the Tsar, presenting himself as a minister plenipotentiary.[21] Despite his claims, he was never given such a commission by the Imperial Government. Efforts were made at cultivating relations with prominent official José Darío Argüello, in order secure a contract for provisions, Rezanov even having a romance with his daughter, Concepción Argüello. However the officials were only willing to forward the request of the Russians to Mexico City, none wanting to disobey a decree by the Spanish Empire that outlawed trade with foreigners. After several months the Russians departed for New Archangel without an agreement for provisions.

Valuable reconnaissance however was gained, with Rezanov seeing first hand the lack of Spanish presidios or settlements until the southern shore of the San Francisco Bay. Several ships owned by Americans were contracted to begin operations in Alta California almost immediately after the Juno's return to New Archangel. One ship was based in Bodega Bay, with its Indigenous Alaskan workforce operating from the coast of modern Mendocino County to the Farallon Islands.[21] While catching otters on the northern shores of the San Francisco Bay, Luis Antonio Argüello, the commandant ordered a cannon be shot at the trappers' baidarkas, dispersing the Aleut and Alutiiq trappers from the Bay.[21] Reports from the American captains and Rezanov on the conditions in California encouraged Chief Manager Baranov to plan a coastal settlement in the territory. There were numerous sea otter populations to hunt, a lack of Spanish military posts above San Francisco Bay, and the possibility to trade with the Spanish Missions.[21]

Fort Ross

Built in 1812 and located on the coast of California in modern-day Sonoma County, Fort Ross was the southernmost outpost of the company. Several additional posts were operated by the Company, including Port Rumyantsev on Bodega Bay, and several ranches south of the Russian River valley. Though on Spanish and then subsequently Mexican territory, the legitimacy of these claims was contested by both the Company and the Russian Government until the sale of the settlement in 1841, basing the legitimacy of their claims on prior English (New Albion) claims of territorial discovery.[22] It is now partially reconstructed and an open-air museum, with the Rotchev House being the only remaining original building.

Proposed colonization

An expansive colonization program of California was presented to the Imperial Court by the "garrulous and unreliable"[23] 20-year-old junior officer and former Decembrist Dmitry I. Zavalishin in late 1824.[24] He had been a crew member of an expedition that during 1823 and 1824 to examine the Russian possessions in North America.[24] His memorandum proposed that the Californios be encouraged to secede from Mexico in order to create a political alliance.[25] Zavalishin wanted the Russian-American Company to receive a grant of land extending north to the border of the Oregon Country, south to the San Francisco Bay and east to either the Sierra Nevada mountains or the Sacramento River.[25] In return the Russians were to maintain a naval presence in San Francisco Bay, protect the California Mission's right to maintain neophyte labor, allow Californios to settle within the grant and establish Spanish language schools throughout California.[25] A council of the inner Russian government debated the merits of Zavalishin's plan. Foreign Minister Count Karl Nesselrode feared the scheme would anger the United States and the United Kingdom, and consequently was against it. The court representative of the RAC, Count Nikolay Mordvinov, defended the memorandum and voiced Zavalishin's stance that "too much leniency and effort to avoid conflict sometimes only precipitate a conflict..."[25]

Building on Zavalishin's proposal, Mordvinov planned on buying serfs from Russian landlords and sending them to California.[25] The freed serfs were to be supported by the Company and had to remain as settlers for seven years in its service. After the expiration of their contracts, all farming implements provided and land farmed upon would become the property of the freemen. A banquet was held for Zavalishin to draw support for his plan, with many prominent officials of the Empire attending.[25] Mikhail Speransky, a former Governor-General of Siberia, saw California as a future grain supplier to Russian Pacific possessions in Alaska, Sakhalin and the Siberian coast. The Assistant Foreign Minister, Poletica, while at first against Zavalishin's program of Californian expansionism, by the end of the reception became fully supportive of it. Additionally the Minister of Education, Shishkov, while not present at the banquet warmly received the memorandum.

Zavalishin became fearful the treaties made in 1824 and 1825 that delineated Russian America's borders would restrict the Empire from a proactive policy in North America. He beseeched Tsar Alexander I for an audience to defend his memorandum, but a meeting was never arranged.[25] Eventually Tsar Alexander echoed Nesselrode's position and refused to send Zavalishin back to California. The political upheaval of Alexander I's death and the subsequent Decembrist Uprising halted the considerations for an extensive commercial colonisation of California by the RAC.[25] In 1853 Governor General N. N. Muravyov recounted to Tsar Alexander II that: California during the 1820s "was unoccupied and virtually unprocessed by anybody", though he found that a "foothold in California" would "sooner or later" have to be turned over to the advancing Americans.[26]

Later period

In 1818 the Russian government had taken control of the Russian-American Company from the merchants who held the charter. Starting in the 1820s the company's profitability slumped due to declining populations of fur bearing animals. It had already had bad annual returns, in 1808 slightly less than half of the 2,300,000 rubles of expense were covered.[3] Starting in 1797 with its forerunner the United American Company to 1821 the RAC collected the following inventory of furs, worth in total 16 million rubles: 1.3 million foxes of several species, 72,894 sea otters, 59,530 river otters, 34,546 beavers, 30,950 sables, 17,298 wolverines, 14,969 fur seals along with smaller numbers of lynx, wolf, sea lion, walrus and bears.[27]

In 1828, Emperor Alexander I ordered that the RAC begin to supply the Russian settlements on the Kamchatka Peninsula, such as Petropavlovsk, with salt. The company was expected to ship between 3,000 and 5,000 Poods of salt annually.[28] Continual difficulties at securing large amounts of cheap salt in the Kingdom of Hawaii and Alta California led officials to consider Baja California instead. Arvid Etholén was dispatched in the winter of 1827, quickly securing permission from Mexican authorities to gather salt around San Quintín.[28] Transportation was arranged with the Misión Santo Tomás.

The explorer and naval officer, Baron Ferdinand Petrovich von Wrangel, who had been administrator of imperial government interests in Russian America a decade before, was the fifth governor during the government period. Eventually during the 1840s the governing board of the company was replaced with a five-member administration of imperial naval officers.[3]

During the Crimean War, officials of the RAC began to fear an invasion of their Alaskan settlements by British forces. Discussions with the Hudson's Bay Company were began in the spring of 1854, with each company pledged to continue peaceable relations and to press their respective governments to do the same.[26] The United Kingdom of Britain and the Russian Empire accepted the deal by the companies, but both governments specified that naval blockades and seizure of vessels were acceptable actions.[26] The British HMS Pique and the French Sibylle, attacked a RAC outpost on Urup Island of the Kuriles in 1855, from the belief the Kuriles weren't covered by the agreement.[29]

The company built a whaling station at Mamga in Tugursky Bay in the Sea of Okhotsk in 1862. It operated from 1863 to 1865 before being sold to Otto Wilhelm Lindholm. Two schooners used the station as a base, sending out whaleboats to catch bowhead whales, which were towed ashore and processed at a nearby tryworks.[30]

The Russian-American Company has been appraised as ran with "poorly chosen and inadequately skilled staff", floundering in part from "the lack of experience of the executives handling an organization which overreached itself through its expansion across the Pacific and along the American coast into California..."[3] The company ceased its commercial activities in 1881. In 1867, the Alaska Purchase transferred control of Alaska to the United States and the commercial interests of the Russian-American Company were sold to Hutchinson, Kohl & Company of San Francisco, California, who then renamed their company to the Alaska Commercial Company.

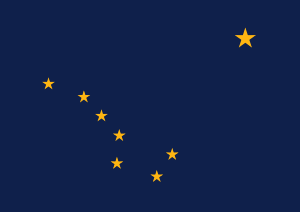

Russian-American Company flag

The Russian commercial flag (civil ensign) was used between 1799 and 1806 by the company on its ships and establishments. Tsar Alexander I approved a design for a separate flag for the RAC on Template:OldStylesDates, writing "So be it" upon the report.[31] After being sent to the State Council, it was forwarded to the FinanceSaint Petersburg and Naval ministries, along with the Saint Petersburg office of the RAC on 19 October 1806 O.S.[32] The memorandum described the flag as having "three stripes, the lower red, the middle blue, and the upper and wider stripe white, with the facsimile on it of the All-Russia state coat-of-arms below which is a ribbon hanging from the talons of the eagle with the inscription thereon 'Russo-American Company's."[32]

The company flag eventually had several variations, in part from the nature of individual production and the changing designs of the Imperial flag. As researcher John Middleton noted "There continues to be much discussion concerning the design of the company flag, mostly centered around the design and placement of the eagle."[32] The various flags flew over the company's holdings in California until 1 January 1842, and over Alaska until 18 October 1867, when all Russian-American Company holdings in Alaska were sold to the United States. The flag continued to represent the company until its Russian holdings were liquidated in 1881.[31]

Chief Managers

Below is a list of the general managers (or chief managers, usually known in English as governors) of the Russian-American Company. Many of their names occur as place names in Southeast Alaska. Note that the English spelling of the names varies between sources. The position administered the commercial operations of the company, centered on Russian America. Alexander Andreyevich Baranov was the first and longest serving chief manager, previously managing the United American Company. After Baranov's tenure, appointees were chosen from the Imperial Russian Navy and generally served terms of five years. 13 naval officers acted as chief managers over the course of the company.

| № | Portrait | Name (Birth–Death) |

Term of Office |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  | Alexander Andreyevich Baranov (1747–1819) | July 9, 1799 – January 11, 1818[33] |

| 2 |  | Captain Ludwig von Hagemeister (1780–1833) | January 11, 1818 – October 24, 1818[33] |

| 3 |  | Lieutenant Semyon Ivanovich Yanovsky (1788–1876) | October 24, 1818 – September 15, 1820[33] |

| 4 |  | Lieutenant Matvey Ivanovich Muravyev (1784–1826) | September 15, 1820 – October 14, 1825[33] |

| 5 |  | Pyotr Yegorovich Chistyakov (1790–1862) | October 14, 1825 – June 1, 1830[33] |

| 6 |  | Baron Ferdinand Petrovich von Wrangel (1797–1870) | June 1, 1830 – October 29, 1835[33] |

| 7 |  | Ivan Antonovich Kupreyanov (1800–1857) | October 29, 1835 – May 25, 1840[33] |

| 8 |  | Arvid Adolf Etholén (1798–1876) | May 25, 1840 – July 9, 1845[33] |

| 9 |  | Vice Admiral Mikhail Dmitrievich Tebenkov (1802–1872) | July 9, 1845 – October 14, 1850[33] |

| 10 |  | Captain Nikolay Yakovlevich Rosenberg (1807–1857) | October 14, 1850 – March 31, 1853[33] |

| 11 |  | Aleksandr Ilich Rudakov (1817–1875) | March 31, 1853 – April 22, 1854[33] |

| 12 |  | Captain Stepan Vasiliyevich Voyevodsky (1805–1884) | April 22, 1854 – June 22, 1859[33] |

| 13 |  | Captain Johan Hampus Furuhjelm (1821–1909) | June 22, 1859 – December 2, 1863[33] |

| 14 |  | Prince Dmitri Petrovich Maksutov (1832–1889) | December 2, 1863 – October 18, 1867[33] |

Settlements

In Alaska

- Unalaska – 1774

- Three Saints Bay – 1784

- Fort St. George in Kasilof – 1786

- Fort Nikolaevskaia in Kenai – 1787

- St. Paul – 1788

- Pavlovskaya – 1791

- Fort Saints Constantine and Helen on Nuchek Island – 1793

- Fort on Hinchinbrook Island – 1793

- New Russia near present-day Yakutat – 1795

- Redoubt St. Archangel Michael near Sitka – 1799

- New Archangel – 1804

- Fort (New) Alexandrovsk at Bristol Bay – 1819

- Redoubt St. Michael – 1833

- Nulato – 1834

- Redoubt St. Dionysius in present-day Wrangell – 1834

- Pokrovskaya Mission – 1837

- Kolmakov Redoubt – 1844

Outside Alaska

- Fort Ross near Healdsburg, California – 1812

- Fort Elizabeth near Waimea, Hawaii – 1817

- Fort Alexander near Hanalei, Hawaii – 1817

- Fort Barclay-de-Tolly near Hanalei, Hawaii – 1817

Ships

- Alexander Nevsky, wrecked in 1813 at the Kurile Islands

- Aleksei Chelovek Bozhii

- Andrei Pervozvannyi

- Andrian i Natalia

- Avos, wrecked in 1808 at Icy Straight.

- Bering, bought from a Boston skipper. Ran aground in the Sandwich Islands (Hawaiian Islands), date unknown.

- Boris i Gleb

- Chirikov, built in New Archangel

- Diana

- Dmitrii

- Yekaterina

- Yelizaveta

- Yevdokim

- Yevpl

- Finlyandiya, built in 1809

- Fish

- Gavril

- Georgy

- Grigory Pobedonosets

- Ieremiya

- Il'mena, purchased from Americans

- Ioann

- Ioann

- Ioann

- Ioann Bogoslov

- Ioann Predtecha

- Ioann Rylsky

- Ioann Zlatoust

- Iulian

- Iunona, wrecked in 1811 at the Viliui River

- Kadiak, a former English ship known as the Myrtle

- Kapiton

- Kapiton (2nd)

- Kapiton (Basov)

- Kliment

- Konstantin

- Kutuvzov

- Maria Magdalina, wrecked in 1816 near the Okhota River

- Mikhail

- Mikhail

- Morekhod

- Nadezhda, wrecked 1808 off Malmö

- Natalia

- Neva, wrecked in January 1813 at Sitka Island

- Nikolai, wrecked in 1808 north of the Quillayute River

- Nikolai

- Nikolai

- Nikolai

- Orel

- Otkrytie, built in New Archangel

- Pavel (Ocheredin)

- Pavel

- Pavel

- Pyotr i Pavel

- Perkup i Zand

- Phoenix

- Predpriyatie Alexander

- Prokofy

- Rostislav

- Severny Orel

- Sikurs

- Simeon

- Simeon i Ioann

- Sitka, built in New Archangel

- Suvorov

- Trekh Ierarkhov

- Trekh Svyatitelei

- Truvor, purchased from Americans

- Vasily

- Vladimir

- Zakharia i Yelizaveta

- Zakhariia i Yelizaveta

- Zosima i Savati

References:

Pierce, Richard, ed. Documents on the history of the Russian-American Company. Kingston, Ont. : Limestone Press, c1976. pp. 23–26. OCLC: 2945773.

Tikhmenev, P. A. A history of the Russian-American Company. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1978. pp. 146–151. OCLC: 3089256.

See also

References

- 1 2 Records of the Russian-American Company National Archives and Records Administration,

- ↑ Pierce, Richard A.: The Russian-American Company: Correspondence of the Governors; Communications Sent: 1818.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Mazour, Anatole G. The Russian-American Company: Private or Government Enterprise? Pacific Historical Review 13, No. 2 (1944), pp. 168-173.

- 1 2 3 4 Lightfoot, Kent G. Russian Colonization: The Implications of Mercantile Colonial Practices in the North Pacific. Historical Archaeology 37, No. 4 (2003), pp. 14-28.

- ↑ Begg, Alexander (1900). "Review of the Alaska Boundary Question". http://www.nosracines.ca. Unknown. pp. 1–2. Retrieved 12 December 2014. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ Haycox, Stephen W. (2002). Alaska: An American Colony. University of Washington Press. pp. 1118–1122. ISBN 978-0-295-98249-6.

- ↑ Macmillan's magazine - Google Boeken. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2012-07-25.

- 1 2 Sladkovskii, Mikhail I. History of Economic Relations between Russia and China. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. 2008, p. 61.

- 1 2 Baltic, Alix. The Baltic Connection in Russian America. Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas, Neue Folge 42, No. 3 (1994), pp. 321-339.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Wheeler, Mary E. Empires in Conflict and Cooperation: The "Bostonians" and the Russian-American Company. Pacific Historical Review 40, No. 4 (1971), pp. 419-441.

- 1 2 Wilson, Joseph R. The Oregon Question. I. The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society 1, No. 2 (1900), 111-131.

- 1 2 Khlebnikov, K.T., 1973, Baranov, Chief Manager of the Russian Colonies in America, Kingston: The Limestone Press, ISBN 0919642500

- ↑ Langsdorff, Grigory. Langsdorff's Narrative of the Rezanov voyage to Nueva California in 1806. Translator Thomas C. Russell. San Francsico, CA: The Private Press of Thomas C. Russell. 1927, p. 21.

- ↑ Spencer-Hancock, Diane, William E. Pritchard and Ina Kaliakin. Notes to the 1817 Treaty between the Russian American Company and Kashaya Pomo Indians. California History 59, No. 4 (1980/1981), pp 306-313.

- 1 2 Alton S. Donnelly. The Wreck of the Sv. Nikolai ed. Kenneth N. Owens. Portland, OR: The Press of the Oregon Historical Society. 1985, p. 4.

- ↑ Donnelly (1985), pp. 44-46.

- ↑ Donnolly (1985), pp. 52-53.

- ↑ Donnolly (1985) pp. 56-59.

- 1 2 Donnolly (1985), pp. 63-65.

- 1 2 3 Andrews, C. L. The story of Alaska. 5 ed. Caldwell, ID: The Caxton Printers. 1942, p. 86.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Owens, Kenneth N. Frontiersman for the Tsar: Timofei Tarakanov and the Expansion of Russian America. Montana: The Magazine of Western History 56, No. 3 (2006), pp. 3-21+93-94.

- ↑ I.F. Kruzenstern, "Notes on ports and Ross and Franchesko" 4th October, 1825. Russia in California 2005.

- ↑ Raeff, Marc. An American View of the Decembrist Revolt. The Journal of Modern History 25, No. 3 (1953), pp. 286-293.

- 1 2 Gibson, James R. The Decembrists. Fort Ross Conservancy Library.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Mazour, Anatole G. Dimitry Zavalishin: Dreamer of a Russian-American Empire. Pacific Historic Review 5, No. 1 (1936), pp. 26-37.

- 1 2 3 Bolkhovitinov, Nikolay N. The Crimean War and the Emergence of Proposals for the Sale of Russian America, 1853-1861. Pacific Historical Review 59, No. 1 (1990), pp. 15-49

- ↑ Tikhmenev (1978), p. 153.

- 1 2 Tikhmenev (1978), pp. 223-224.

- ↑ Tikhmenev (1978), p. 356.

- ↑ Lindholm, O. V., Haes, T. A., & Tyrtoff, D. N. (2008). Beyond the frontiers of imperial Russia: From the memoirs of Otto W. Lindholm. Javea, Spain: A. de Haes OWL Publishing.

- 1 2 Бытъ По Сему “So Be It.” 200 Years of the History and Interpretation of“The flag granted by His Imperial Highness. Fort Ross Interpretive Association Newsletter, Winter 2006 - 2007, pp. 2-4. (Accessed 14 October 2014)

- 1 2 3 Federova, Svetlana G. The Flag of the Russian-American Company. Fort Ross Conservancy Library. (Accessed 14 October 2014)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Andrews (1942), p. 302.

Further reading

- Grinyov, Andrei V., “A Failed Monopoly: Management of the Russian-American Company, 1799–1867,” Alaska History, 27 (Spring–Fall 2012), 19–47.

- A. I. Istomin, J. Gibson, V. A. Tishkov. Russia in California. Nauk, Moscow 2005

- Middleton, John. Бытъ По Сему- So be it: 200 years of the history and interpretation of "The flag granted by his Imperial Highness" The flag of the Russian-American Company. September, 2006. Fort Ross Conservancy web site

Primary sources

- Pierce, Richard A.:The Russian-American Company: Correspondence of the Governors; Communications Sent: 1818 The Limestone Press Kingston, Ontario, Canada 1984.

- I.F. Kruzenstern: Notes on ports and Ross and Franchesko, 4 October 1825.

- Vorobyoff, Igor V., trans. (1973) "Adventures of Doctor Schäffer in Hawaii, 1815–1819," Hawaiian Journal of History 7:55–78 (translation of Bolkhovitinov, N. N., "Avantyura Doktora Sheffera na Gavayyakh v 1815–1819 Godakh," Novaya i Noveyshaya Istoriya 1[1972]:121–137)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Russian-American Company. |

- Russian-American Company walrus skin banknotes

- The Russian-American Company and the Northwest Fur Trade: North American Scholarship, 1990–2000