Russian Ground Forces

| Ground Forces of the Russian Federation Сухопутные войска Российской Федерации Suhoputnye voyska Rossiyskoy Federatsii | |

|---|---|

|

Emblem of the Russian Ground Forces | |

| Active |

1992 – present (current form) |

| Country | Russia |

| Allegiance | Ministry of Defence |

| Type | Army |

| Size | 230,000 personnel (2015), does not include Airborne Troops (VDV) [1] |

| Part of | Russian Armed Forces |

| Headquarters | Frunzenskaya Embankment 20-22, Moscow |

| Anniversaries | 1 October |

| Engagements |

Transnistria War Civil War in Tajikistan East Prigorodny conflict War in Abkhazia 1993 Russian constitutional crisis First Chechen War War of Dagestan Second Chechen War Russo-Georgian War Insurgency in the North Caucasus 2014–15 Russian military intervention in Ukraine[2] Syrian Civil War |

| Commanders | |

| Current commander |

Colonel General Oleg Salyukov (since 2 May 2014)[3] |

| Insignia | |

| Flag |

|

| Great Emblem |

|

| Patch |

|

The Ground Forces of the Russian Federation (Russian: Сухопутные войска Российской Федерации, tr. Suhoputnye voyska Rossiyskoy Federatsii) are the land forces of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation, formed from parts of the collapsing Soviet Army in 1992. The formation of these forces posed economic challenges after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, and required reforms to professionalize the force during the transition.

Since 1992, the Ground Forces have withdrawn many thousands of troops from former Soviet garrisons abroad, while remaining extensively committed to the Chechen Wars, peacekeeping, and other operations in the Soviet successor states (what is known in Russia as the "near abroad").

Mission

The primary responsibilities of the Ground Forces are the protection of the state borders, combat on land, the security of occupied territories, and the defeat of enemy troops. The Ground Forces must be able to achieve these goals both in nuclear war and non-nuclear war, especially without the use of weapons of mass destruction. Furthermore, they must be capable of protecting the national interests of Russia within the framework of its international obligations.

The Main Command of the Ground Forces is officially tasked with the following objectives:[4]

- The training of troops for combat, on the basis of tasks determined by the Armed Forces' General Staff.

- The improvement of troops' structure and composition, and the optimization of their numbers, including for special troops.

- The development of military theory and practice.

- The development and introduction of training field manuals, tactics, and methodology.

- The improvement of operational and combat training of the Ground Forces.

History

| Armies of Russia | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

|

||||||

|

| ||||||

|

||||||

|

| ||||||

|

||||||

|

| ||||||

|

||||||

|

| ||||||

|

||||||

|

| ||||||

|

||||||

|

| ||||||

| Armed Forces of the Russian Federation |

|---|

.svg.png)  .svg.png) |

| Services (vid) |

| Independent troops (rod) |

| Other troops |

| Ranks of the Russian Military |

| History of the Russian military |

As the Soviet Union dissolved, efforts were made to keep the Soviet Armed Forces as a single military structure for the new Commonwealth of Independent States. The last Minister of Defence of the Soviet Union, Marshal Yevgeny Shaposhnikov, was appointed supreme commander of the CIS Armed Forces in December 1991.[5] Among the numerous treaties signed by the former republics, in order to direct the transition period, was a temporary agreement on general purpose forces, signed in Minsk on 14 February 1992. However, once it became clear that Ukraine (and potentially the other republics) was determined to undermine the concept of joint general purpose forces and form their own armed forces, the new Russian government moved to form its own armed forces.[5]

President of the Russian Federation Boris Yeltsin signed a decree forming the Russian Ministry of Defence on 7 May 1992, establishing the Russian Ground Forces along with the other parts of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation. At that time, the General Staff was in the process of withdrawing tens of thousands of personnel from the Group of Soviet Forces in Germany, the Northern Group of Forces in Poland, the Central Group of Forces in Czechoslovakia, the Southern Group of Forces in Hungary, and from Mongolia.

Thirty-seven divisions had to be withdrawn from the four groups of forces and the Baltic States, and four military districts—totalling 57 divisions—were handed over to Belarus and Ukraine.[6] Some idea of the scale of the withdrawal can be gained from the division list. For the dissolving Soviet Ground Forces, the withdrawal from the former Warsaw Pact states and the Baltic states was an extremely demanding, expensive, and debilitating process.[7] As the military districts that remained in Russia after the collapse of the Union consisted mostly of the mobilisable cadre formations, the Russian Ground Forces were, to a large extent, created by relocating the formerly full-strength formations from Eastern Europe to those under-resourced districts. However, the facilities in those districts were inadequate to house the flood of personnel and equipment returning from abroad, and many units "were unloaded from the rail wagons into empty fields."[8] The need for destruction and transfer of large amounts of weaponry under the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe also necessitated great adjustments.

Post-Soviet reform plans

The Ministry of Defence newspaper Krasnaya Zvezda published a reform plan on 21 July 1992. Later one commentator said it was "hastily" put together by the General Staff "to satisfy the public demand for radical changes."[9] The General Staff, from that point, became a bastion of conservatism, causing a build-up of troubles that later became critical. The reform plan advocated a change from an Army-Division-Regiment structure to a Corps-Brigade arrangement. The new structures were to be more capable in a situation with no front line, and more capable of independent action at all levels. Cutting out a level of command, omitting two out of three higher echelons between the theatre headquarters and the fighting battalions, would produce economies, increase flexibility, and simplify command-and-control arrangements.[10] The expected changeover to the new structure proved to be rare, irregular, and sometimes reversed. The new brigades that appeared were mostly divisions that had broken down until they happened to be at the proposed brigade strengths. New divisions—such as the new 3rd Motor Rifle Division in the Moscow Military District, formed on the basis of disbanding tank formations—were formed, rather than new brigades.

Few of the reforms planned in the early 1990s eventuated, for three reasons: Firstly, there was an absence of firm civilian political guidance, with President Yeltsin primarily interested in ensuring that the Armed Forces were controllable and loyal, rather than reformed.[9][11] Secondly, declining funding worsened the progress. Finally, there was no firm consensus within the military about what reforms should be implemented. General Pavel Grachev, the first Russian Minister of Defence (1992–96), broadly advertised reforms, yet wished to preserve the old Soviet-style Army, with large numbers of low-strength formations and continued mass conscription. The General Staff and the armed services tried to preserve Soviet era doctrines, deployments, weapons, and missions in the absence of solid new guidance.[12]

A British military expert, Michael Orr, claims that the hierarchy had great difficulty in fully understanding the changed situation, due to their education. As graduates of Soviet military academies, they received great operational and staff training, but in political terms they had learned an ideology, rather than a wide understanding of international affairs. Thus, the generals—focused on NATO expanding to the east—could not adapt themselves and the Armed Forces to the new opportunities and challenges they faced.[13]

Internal crisis of 1993

The Ground Forces reluctantly became involved in the Russian constitutional crisis of 1993 after President Yeltsin issued an unconstitutional decree dissolving the Parliament, following the Parliament's resistance to Yeltsin's consolidation of power and his neo-liberal reforms. A group of deputies, including Vice President Alexander Rutskoi, barricaded themselves inside the Parliament building. While giving public support to the President, the Armed Forces, led by General Grachev, tried to remain neutral, following the wishes of the officer corps.[14] The military leadership were unsure of both the rightness of Yeltsin's cause and the reliability of their forces, and had to be convinced at length by Yeltsin to attack the Parliament.

When the attack was finally mounted, forces from five different divisions around Moscow were used, and the personnel involved were mostly officers and senior non-commissioned officers.[7] There were also indications that some formations deployed into Moscow only under protest.[14] However, once Parliament had been stormed, the parliamentary leaders arrested, and temporary censorship imposed, Yeltsin succeeded in retaining power.

Chechen Wars

First Chechen War

The Chechen people had never willingly accepted Russian rule. With the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the Chechens declared independence in November 1991, under the leadership of a former Air Forces officer, General Dzhokar Dudayev.[15] The continuation of Chechen independence was seen as reducing Moscow's authority; Chechnya became perceived as a haven for criminals, and a hard-line group within the Kremlin began advocating war. A Security Council meeting was held 29 November 1994, where Yeltsin ordered the Chechens to disarm, or else Moscow would restore order. Defense Minister Pavel Grachev assured Yeltsin that he would "take Grozny with one airborne assault regiment in two hours."[16]

The operation began on 11 December 1994 and, by 31 December, Russian forces were entering Grozny, the Chechen capital. The 131st Motor Rifle Brigade was ordered to make a swift push for the centre of the city, but was then virtually destroyed in Chechen ambushes. After finally seizing Grozny amid fierce resistance, Russian troops moved on to other Chechen strongholds. When Chechen militants took hostages in the Budyonnovsk hospital hostage crisis in Stavropol Kray in June 1995, peace looked possible for a time, but the fighting continued. Following this incident, the separatists were referred to as insurgents or terrorists within Russia.

Dzhokar Dudayev was assassinated in April 1996, and that summer, a Chechen attack retook Grozny. Alexander Lebed, then Secretary of the Security Council, began talks with the Chechen rebel leader Aslan Maskhadov in August 1996 and signed an agreement on 22/23 August; by the end of that month, the fighting ended.[17] The formal ceasefire was signed in the Dagestani town of Khasavyurt on 31 August 1996, stipulating that a formal agreement on relations between the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria and the Russian federal government need not be signed until late 2001.

Writing some years later, Dmitri Trenin and Aleksei Malashenko described the Russian military's performance in Chechniya as "grossly deficient at all levels, from commander-in-chief to the drafted private."[18] The Ground Forces' performance in the First Chechen War has been assessed by a British academic as "appallingly bad".[19] Writing six years later, Michael Orr said "one of the root causes of the Russian failure in 1994–96 was their inability to raise and deploy a properly trained military force."[20]

Second Chechen War

The Second Chechen War began in August 1999 after Chechen militias invaded neighboring Dagestan, followed quickly in early September by a series of four terrorist bombings across Russia. This prompted Russian military action against the alleged Chechen culprits.

In the first Chechen war, the Russians primarily laid waste to an area with artillery and airstrikes before advancing the land forces. Improvements were made in the Ground Forces between 1996 and 1999; when the Second Chechen War started, instead of hastily assembled "composite regiments" dispatched with little or no training, whose members had never seen service together, formations were brought up to strength with replacements, put through preparatory training, and then dispatched. Combat performance improved accordingly,[21] and large-scale opposition was crippled.

Most of the prominent past Chechen separatist leaders had died or been killed, including former president Aslan Maskhadov and leading warlord and terrorist attack mastermind Shamil Basayev. However, small-scale conflict continued to drag on; as of November 2007, it had spread across other parts of the Russian Caucasus.[22] It was a divisive struggle, with at least one senior military officer dismissed for being unresponsive to government commands: General Colonel Gennady Troshev was dismissed in 2002 for refusing to move from command of the North Caucasus Military District to command of the less important Siberian Military District.[23]

The Second Chechen War was officially declared ended on 16 April 2009.[24]

Reforms under Sergeyev

When Igor Sergeyev arrived as Minister of Defence in 1997, he initiated what were seen as real reforms under very difficult conditions.[25] The number of military educational establishments, virtually unchanged since 1991, was reduced, and the amalgamation of the Siberian and Trans-Baikal Military Districts was ordered. A larger number of army divisions were given "constant readiness" status, which was supposed to bring them up to 80 percent manning and 100 percent equipment holdings. Sergeyev announced in August 1998 that there would be six divisions and four brigades on 24-hour alert by the end of that year. Three levels of forces were announced; constant readiness, low-level, and strategic reserves.[26]

However, personnel quality—even in these favored units—continued to be a problem. Lack of fuel for training and a shortage of well-trained junior officers hampered combat effectiveness.[27] However, concentrating on the interests of his old service, the Strategic Rocket Forces, Sergeyev directed the disbanding of the Ground Forces headquarters itself in December 1997.[28] The disbandment was a "military nonsense", in Orr's words, "justifiable only in terms of internal politics within the Ministry of Defence".[29] The Ground Forces' prestige declined as a result, as the headquarters disbandment implied—at least in theory—that the Ground Forces no longer ranked equally with the Air Force and Navy.[29]

Reforms under Putin

Under President Vladimir Putin, more funds were committed, the Ground Forces Headquarters was reestablished, and some progress on professionalisation occurred. Plans called for reducing mandatory service to 18 months in 2007, and to one year by 2008, but a mixed Ground Force, of both contract soldiers and conscripts, would remain. (As of 2009, the length of conscript service was 12 months.)[30]

Funding increases began in 1999; after some recovery in the Russian economy and the associated rise in income, especially from oil, "Russia's officially reported defence spending [rose] in nominal terms at least, for the first time since the formation of the Russian Federation".[31] The budget rose from 141 billion rubles in 2000 to 219 billion rubles in 2001.[32] Much of this funding has been spent on personnel—there have been several pay rises, starting with a 20-percent rise authorised in 2001; the current professionalisation programme, including 26,000 extra sergeants, was expected to cost at least 31 billion roubles ($1.1 billion USD).[33] Increased funding has been spread across the whole budget, with personnel spending being matched by greater procurement and research and development funding.

However, in 2004, Alexander Goltz said that, given the insistence of the hierarchy on trying to force contract soldiers into the old conscript pattern, there is little hope of a fundamental strengthening of the Ground Forces. He further elaborated that they are expected to remain, to some extent, a military liability and "Russia's most urgent social problem" for some time to come.[34] Goltz summed up by saying: "All of this means that the Russian armed forces are not ready to defend the country and that, at the same time, they are also dangerous for Russia. Top military personnel demonstrate neither the will nor the ability to effect fundamental changes."[34]

More money is arriving both for personnel and equipment; Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin said in June 2008 that monetary allowances for servicemen in permanent-readiness units will be raised significantly.[35] In May 2007, it was announced that enlisted pay would rise to 65,000 roubles (US$2,750) per month, and the pay of officers on combat duty in rapid response units would rise to 100,000–150,000 roubles (US$4,230–$6,355) per month. However, while the move to one year conscript service would disrupt dedovshchina, it is unlikely that bullying will disappear altogether without significant societal change.[36] Other assessments from the same source point out that the Russian Armed Forces faced major disruption in 2008, as demographic change hindered plans to reduce the term of conscription from two years to one.[37] As a result of these factors and continuing corruption, the additional funding may not have led to a large improvement in the Russian Army's effectiveness.[38]

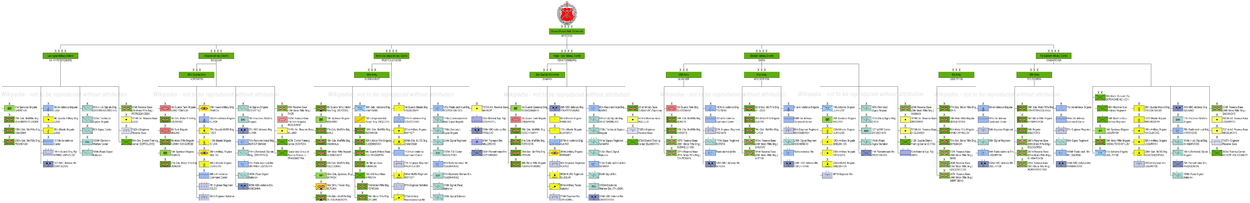

Serdukov reforms

A major reorganisation of the force began in 2007 by the Minister for Defence Anatoliy Serdukov, with the aim of converting all divisions into brigades, and cutting surplus officers and establishments.[39][40] However, this affected units of continuous readiness (Russian: ЧПГ - части постоянной готовности) only. It is intended to create 39 to 40 such brigades by 1 January 2016, including 39 all-arms brigades, 21 artillery and MRL brigades, seven brigades of army air defence forces, 12 communication brigades, and two electronic warfare brigades. In addition, the 18th Machine Gun Artillery Division stationed in the Far East remained, and there will be an additional 17 separate regiments. The reform has been called "unprecedented".

In the course of the reorganization, the 4-chain command structure (military district - field army - division - regiment) that was used until then was replaced with a 3-chain structure: strategic command - operational command - brigade. Brigades are supposed to be used as mobile permanent-readiness units capable of fighting independently with the support of highly mobile task forces or together with other brigades under joint command.[41]

In a statement on 4 September 2009, RGF Commander-in-Chief Vladimir Boldyrev said that half of the Russian land forces were reformed by 1 June and that 85 brigades of constant combat preparedness had already been created. Among them are the combined-arms brigade, missile brigades, assault brigades and electronic warfare brigades.[42]

Structure

The President of Russia is the Supreme Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation. The Main Command (Glavkomat) of the Ground Forces, based in Moscow, directs activities. This body was disbanded in 1997, but reformed by President Putin in 2001 by appointing Colonel General Nikolai Kormiltsev as the commander-in-chief of the ground forces and also as a deputy minister of defense.[43] Kormiltsev handed over command to Colonel General (later General of the Army) Alexey Maslov in 2004, and in a realignment of responsibilities, the Ground Forces Commander-in-Chief lost his position as a deputy minister of defence. Like Kormiltsev, while serving as Ground Forces Commander-in-Chief Maslov has been promoted to General of the Army.

As of January 2014, the acting commander of the Russian Ground Forces is Lieutenant General Sergei Istrakov, who was appointed by Russian president Vladimir Putin upon the dismissal of former commander Colonel General Vladimir Chirkin over corruption charges in December 2013.[44][45] Istrakov handed over to a new commander on 2 May 2014, Colonel general Oleg Salyukov.

The Main Command of the Ground Forces consists of the Main Staff of the Ground Troops, and departments for Peacekeeping Forces, Armaments of the Ground Troops, Rear Services of the Ground Troops, Cadres of the Ground Troops (personnel), Indoctrination Work, and Military Education.[46] There were also a number of directorates which used to be commanded by the Ground Forces Commander-in-Chief in his capacity as a deputy defence minister. They included Radiation, Chemical, and Biological Defence Troops of the Armed Forces, Engineer Troops of the Armed Forces, and Troop Air Defence, as well as several others. Their exact command status is now unknown.

Branches of service

The branches of service include motorized rifles, tanks, artillery and rocket forces, troop air defense, special corps (reconnaissance, signals, radioelectronic warfare, engineering, radiation, chemical and biological protection, technical support, automobile, and the protection of the rear), military units, and logistical establishments.[47]

The Motorised Rifle Troops, the most numerous branch of service, constitutes the nucleus of Ground Forces' battle formations. They are equipped with powerful armament for destruction of ground-based and aerial targets, missile complexes, tanks, artillery and mortars, anti-tank guided missiles, anti-aircraft missile systems and installations, and means of reconnaissance and control. It is estimated that there are currently 19 motor rifle divisions, and the Navy now has several motor rifle formations under its command in the Ground and Coastal Defence Forces of the Baltic Fleet, the Northeastern Group of Troops and Forces on the Kamchatka Peninsula and other areas of the extreme northeast.[48] Also present are a large number of mobilisation divisions and brigades, known as "Bases for Storage of Weapons and Equipment", that in peacetime only have enough personnel assigned to guard the site and maintain the weapons.

The Tank Troops are the main impact force of the Ground Forces and a powerful means of armed struggle, intended for the accomplishment of the most important combat tasks. As of 2007, there were three tank divisions in the force: the 4th and 10th within the Moscow Military District, and 5th Guards "Don" in the Siberian MD.[49] The 2nd Guards Tank Division in the Siberian Military District and the 21st Tank Division in the Far Eastern MD were disbanded.

The Artillery and Rocket Forces provide the Ground Forces' main firepower. The Ground Forces currently include five or six static defence machine-gun/artillery divisions and seemingly now one division of field artillery—the 34th Guards in the Moscow MD. The previous 12th in the Siberian MD, and the 15th in the Far Eastern MD, seem to have disbanded.[50]

The Air Defense Troops (PVO) are one of the basic weapons for the destruction of enemy air forces. They consist of surface-to-air missiles, anti-aircraft artillery and radio-technical units and subdivisions.[51]

Army Aviation, while intended for the direct support of the Ground Forces, has been under the control of the Air Forces (VVS)[52] since 2003. However, by 2015, Army Aviation will have been transferred back to the Ground Forces and 18 new aviation brigades will have been added.[53] Of the around 1,000 new helicopters that have been ordered under the State Armament Programmes, 900 will be for the Army Aviation.[54]

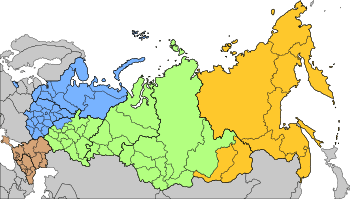

Dispositions since 2010

As a result of the 2008 Russian military reforms, the ground forces now consist of armies subordinate to the four new military districts: (Western, Southern, Central, and Eastern Military Districts). The new districts have the role of 'operational strategic commands,' which command the Ground Forces as well as the Naval Forces and part of the Air and Air Defence Forces within their areas of responsibility.[55]

Each major formation is bolded, and directs the non-bolded major subordinate formations. It is not entirely clear to which superior(s) the four operational-strategic commands will report from 1 December 2010, as they command formations from multiple services (Air Force, Ground Forces & Navy). A current detailed list of the subordinate units of the four military districts can be found in the respective articles.[55] During 2009, all 23 remaining divisions were reorganised into four tank brigades, 35 motor-rifle brigades, one prikritiya brigade formed from a machinegun-light artillery division, and three airborne-assault brigades (pre-existing). Almost all are now designated otdelnaya (separate), with only several brigades retaining the guards honorific title.

In 2013, two of these brigades were reactivated as full divisions: the 2nd Guards Tamanskaya Motor Rifle Division and 4th Guards Kantemirovskaya Tank Division.

| Formation | Headquarters Location |

|---|---|

| Western Military District (Colonel General Andrey Kartapolov) | HQ Saint Petersburg |

| * 1st Tank Army | Odintsovo |

| * 6th Army | Agalatovo |

| * 20th Army | Voronezh |

| Southern Military District (Colonel General Aleksandr Dvornikov)[56] | HQ Rostov-na-Donu |

| * 49th Army | Stavropol[57] |

| * 58th Army | Vladikavkaz |

| Central Military District (Colonel General Vladimir Zarudnitsky) | HQ Yekaterinburg |

| * 2nd Army | Samara |

| * 41st Army | Novosibirsk |

| Eastern Military District (Colonel General Sergey Surovikihn) | HQ Khabarovsk |

| * 5th Army | Ussuriysk |

| * 29th Army | Chita, Zabaykalsky Krai |

| * 35th Army | Belogorsk, Amur Oblast |

| * 36th Army | Ulan Ude |

Personnel

In 2006, the Ground Forces included an estimated total of 395,000 persons, including an approximately 190,000 conscripts and 35,000 personnel of the Airborne Forces (VDV).[58] This can be compared to an estimated 670,000, with 210,000 conscripts, in 1995–96.[59] These numbers should be treated with caution, however, due to the difficulty for those outside Russia to make accurate assessments, and confusion even within the General Staff on the numbers of conscripts within the force.[37]

The Ground Forces began their existence in 1992, inheriting the Soviet military manpower system practically unchanged, though it was in a state of rapid decay. The Soviet Ground Forces were traditionally manned through terms of conscription, which had been reduced in 1967 from three to two years. This system was administered through the thousands of military commissariats (Russian: военный комиссариат, военкомат [voyenkomat]) located throughout the Soviet Union. Between January and May of each year, every young Soviet male citizen was required to report to the local voyenkomat for assessment for military service, following a summons based on lists from every school and employer in the area.

The voyenkomat worked to quotas sent out by a department of the General Staff, listing how many young men were required by each service and branch of the Armed Forces.[60] (Since the fall of the Soviet Union, draft evasion has skyrocketed; officials regularly bemoan the ten or so percent that actually appear when summoned.) The new conscripts were then picked up by an officer from their future unit and usually sent by train across the country. On arrival, they would begin the Young Soldiers' course, and become part of the system of senior rule, known as dedovshchina, literally "rule by the grandfathers." There were only a very small number of professional non-commissioned officers (NCOs), as most NCOs were conscripts sent on short courses[61] to prepare them for section commanders' and platoon sergeants' positions. These conscript NCOs were supplemented by praporshchik warrant officers, positions created in the 1960s to support the increased variety of skills required for modern weapons.[62]

The Soviet Army's officer-to-soldier ratio was extremely top-heavy, partially in order to compensate for the relatively low education level of the military manpower base and the absence of professional NCOs. Following World War II and the great expansion of officer education, officers became the product of four-to-five-year higher military colleges.[63] As in most armies, newly commissioned officers usually become platoon leaders, having to accept responsibility for the soldiers' welfare and training (with the exceptions noted above). Young officers in Soviet Army units were worked round the clock, normally receiving only three days off per month. Annual vacations were under threat if deficiencies emerged within the unit, and the pressure created enormous stress. Towards the end of the Soviet Union, this led to a decline in morale amongst young officers.[64]

In the early 2000s, many junior officers did not wish to serve—in 2002, more than half the officers who left the forces did so early.[34] Their morale was low, among other reasons because their postings were entirely in the hands of their immediate superiors and the personnel department. "Without having to account for their actions, they can choose to promote or not promote him, to send him to Moscow or to some godforsaken post on the Chinese border."[34]

There is little available information on the current status of women, who are not conscripted, in the Ground Forces. According to the BBC, there were 90,000 women in the Russian Army in 2002, though estimates on numbers of women across the entire Russian armed forces in 2000 ranged from 115,000 to 160,000.[65][66] Women serve in support roles, most commonly in the fields of nursing, communications, and engineering. Some officers' wives have become contract service personnel.

Contract soldiers

From small beginnings in the early 1990s, employment of contract soldiers (kontraktniki) has grown greatly within the Ground Forces, though many have been of poor quality (wives of officers with no other prospective employment, for example).[8] In December 2005, Sergei Ivanov, then Minister of Defence, proposed that—in addition to the numerous enlisted contract soldiers—all sergeants should become professional, which would raise the number of professional soldiers and non-commissioned officers in the Armed Forces overall to approximately 140,000 in 2008. The current programme allows for an extra 26,000 posts for fully professional sergeants.[67]

The CIA reported in the World Factbook that 30 percent of Russian army personnel were contract servicemen at the end of 2005, and that, as of May 2006, 178,000 contract servicemen were serving in the Ground Forces and the Navy. Planning calls for volunteer servicemen to compose 70 percent of armed forces by 2010, with the remaining servicemen consisting of conscripts. At the end of 2005, the Ground Forces had 40 all-volunteer constant readiness units, with another 20 constant readiness units to be formed in 2006.[30] These CIA figures can be set against IISS data, which reports that at the end of 2004, the number of contracts being signed in the Moscow Military District was only 17 percent of the target figure; in the North Caucasus, 45 percent; and in the Volga-Ural, 25 percent.[68]

Whatever the number of contract soldiers, commentators such as Alexander Goltz are pessimistic that many more combat ready units will result, as senior officers "see no difference between professional NCOs, ... versus conscripts who have been drilled in training schools for less than six months. Such sergeants will have neither the knowledge nor the experience that can help them win authority [in] the barracks."[34] Defence Minister Sergey Ivanov underlined the in-barracks discipline situation, even after years of attempted professionalisation, when releasing the official injury figures for 2002. 531 men had died on duty as a result of accidents and crimes, and 20,000 had been wounded (the numbers apparently not including suicides). According to Ivanov, "the accident rate is not falling".[69] Two of every seven conscripts will become addicted to drugs and alcohol while serving their terms, and a further one in twenty will suffer homosexual rape, according to 2005 reports.[70]

Part of the reason is the feeling between contract servicemen, conscripts, and officers.

There is no relationship of mutual respect between leaders and led and it is difficult to see how a professional army can be created without one. ..at the moment [2002] officers often despise contract servicemen even more than conscripts. Contract soldiers serving in Chechnya and other "hot spots" are often called mercenaries and marauders by senior officers.— Michael Orr[71]

Equipment

The Ground Forces retain a very large quantity of vehicles and equipment.[72] There is also likely to be a great deal of older equipment in state military storage, a practice continued from the Soviet Union. However, following the collapse of the USSR, the newly independent republics became host to most of the formations with modern equipment, whereas Russia was left with lower-category units, usually with older equipment.[73] As financial stringency began to bite harder, the amount of new equipment fell as well, and by 1998, only ten tanks and about 30 BMP infantry fighting vehicles were being purchased each year.[74]

New equipment, like the Armata Universal Combat Platform, Bumerang and Kurganets-25 will be equipped from 2015 and replace many old tanks, BMPs, BTRs like T-72, T-90, BMP-1/2/3, BTR-80 in active service. Funding for new equipment has greatly risen in recent years, and the Russian defence industry continues to develop new weapons systems for the Ground Forces.[75] However, for the Ground Forces, while overall funding has dramatically increased, this does not guarantee that large numbers of new systems will enter service. In the case of vehicles, as the references show, examination of the actual number of vehicles planned to be bought yearly (about 200 MBTs and IFVs/APCs) means that for a force of about thirty divisions, each with about 300–400 MBTs and IFVs, it might take around 30 years to re-equip all formations.[76]

Equipment summary

The following figures are sourced from http://warfare.be. Figures listed as "Active" only include equipment that is deemed serviceable and circulated in active service.

| Type | Active | Reserve |

|---|---|---|

| Main battle tanks | 2,562[77] | ~12,500[78][79] |

| Infantry fighting vehicles | 3,229[80] | ~16,500[81][82] |

| Armoured personnel carriers | 2,876[83] | ~ 5,000[84] |

| Towed artillery | 1,781[85] | |

| Self-propelled artillery | 2,606[86] | |

| Rocket artillery | 1,352[87] | |

| SAM systems | 1,531[88] |

Ranks and insignia

The newly re-emergent Russia retained most of the ranks of the Soviet Army, with some minor changes. The principal difference from the usual Western style is some variation in generals' rank titles—in at least one case, Colonel General, derived from German usage. Most of the rank names were borrowed from existing German/Prussian, French, English, Dutch, and Polish ranks upon the formation of Russian regular army in the late 17th century, and have lasted with few changes of title through the Soviet period.

Crime and corruption in the ground forces

The new Russian Ground Forces inherited an increasing crime problem from their Soviet predecessors. As draft resistance grew in the last years of the Soviet Union, the authorities tried to compensate by enlisting men with criminal records and who spoke little or no Russian. Crime rates soared, with the military procurator in Moscow in September 1990 reporting a 40-percent increase in crime over the previous six months, including a 41-percent rise in serious bodily injuries.[89] Disappearances of weapons rose to rampant levels, especially in Eastern Europe and the Caucasus.[89]

Generals directing the withdrawals from Eastern Europe diverted arms, equipment, and foreign monies intended to build housing in Russia for the withdrawn troops. Several years later, the former commander in Germany, General Matvei Burlakov, and the Defence Minister, Pavel Grachev, had their involvement exposed. They were also accused of ordering the murder of reporter Dmitry Kholodov, who had been investigating the scandals.[89] In December 1996, Defence Minister Igor Rodionov ordered the dismissal of the Commander of the Ground Forces, General Vladimir Semyonov, for activities incompatible with his position — reportedly his wife's business activities.[90]

A 1995 study by the U.S. Foreign Military Studies Office[91] went as far as to say that the Armed Forces were "an institution increasingly defined by the high levels of military criminality and corruption embedded within it at every level." The FMSO noted that crime levels had always grown with social turbulence, such as the trauma Russia was passing through. The author identified four major types among the raft of criminality prevalent within the forces—weapons trafficking and the arms trade; business and commercial ventures; military crime beyond Russia's borders; and contract murder. Weapons disappearances began during the dissolution of the Union and has continued. Within units "rations are sold while soldiers grow hungry ... [while] fuel, spare parts, and equipment can be bought."[71] Meanwhile, voyemkomats take bribes to arrange avoidance of service, or a more comfortable posting.

Beyond the Russian frontier, drugs were smuggled across the Tajik border—supposedly being patrolled by Russian guards—by military aircraft, and a Russian senior officer, General Major Alexander Perelyakin, had been dismissed from his post with the United Nations peacekeeping force in Bosnia-Hercegovina (UNPROFOR), following continued complaints of smuggling, profiteering, and corruption. In terms of contract killings, beyond the Kholodov case, there have been widespread rumours that GRU Spetsnaz personnel have been moonlighting as mafiya hitmen.[92]

Reports such as these continue. Some of the more egregious examples have included a constant-readiness motor rifle regiment's tanks running out of fuel on the firing ranges, due to the diversion of their fuel supplies to local businesses.[71] Visiting the 20th Army in April 2002, Sergey Ivanov said the volume of theft was "simply impermissible".[71]

Some degree of change is under way.[36] Abuse of personnel, sending soldiers to work outside units—a long-standing tradition which could see conscripts doing things ranging from being large scale manpower supply for commercial businesses to being officers' families' servants—is now banned by Sergei Ivanov's Order 428 of October 2005. What is more, the order is being enforced, with several prosecutions recorded.[36] President Putin also demanded a halt to dishonest use of military property in November 2005: "We must completely eliminate the use of the Armed Forces' material base for any commercial objectives."

The spectrum of dishonest activity has included, in the past, exporting aircraft as scrap metal; but the point at which officers are prosecuted has shifted, and investigations over trading in travel warrants and junior officers' routine thieving of soldiers' meals are beginning to be reported.[36] However, British military analysts comment that "there should be little doubt that the overall impact of theft and fraud is much greater than that which is actually detected".[36] Chief Military Prosecutor Sergey Fridinskiy said in March 2007 that there was "no systematic work in the Armed Forces to prevent embezzlement".[36]

In March 2011, Military Prosecutor General Sergei Fridinsky reported that crimes had been increasing steadily in the Russian ground forces for the past 18 months, with 500 crimes reported in the period of January to March 2011 alone. Twenty servicemen were crippled and two killed in the same period as a result. Crime in the ground forces was up 16% in 2010 as compared to 2009, with crimes against other servicemen constituting one in every four cases reported.[93][94] Compounding this problem was also a rise in "extremist" crimes in the ground forces, with "servicemen from different ethnic groups or regions trying to enforce their own rules and order in their units", according to the Prosecutor General. Fridinsky also lambasted the military investigations department for their alleged lack of efficiency in investigative matters, with only one in six criminal cases being revealed. Military commanders were also accused of concealing crimes committed against servicemen from military officials.[95][96]

A major corruption scandal also occurred at the elite Lipetsk pilot training center, where the deputy commander, the chief of staff and other officers allegedly extorted 3 million roubles of premium pay from other officers since the beginning of 2010. The Tambov military garrison prosecutor confirmed that charges have been lodged against those involved. The affair came to light after a junior officer wrote about the extortion in his personal blog. Sergey Fridinskiy, the Main Military Prosecutor acknowledged that extortion in the distribution of supplementary pay in army units is common, and that "criminal cases on the facts of extortion are being investigated in practically every district and fleet.”[97]

In August 2012, Prosecutor General Fridinsky again reported a rise in crime, with murders rising more than half, bribery cases doubling, and drug trafficking rising by 25% in the first six months of 2012 as compared to the same period in the previous year. Following the release of these statistics, the Union of the Committees of Soldiers' Mothers of Russia denounced the conditions in the Russian army as a "crime against humanity".[98]

In July 2013, the Prosecutor General's office revealed that corruption in the same year soared 450% as compared to the previous year, costing the Russian government 4.4 billion rubles (US$130 million), with one in three corruption-related crimes committed by civil servants or civilian personnel in the military forces. It was also revealed that total number of registered crimes in the Russian armed forces had declined in the same period, although one in five crimes registered were corruption-related.[99]

See also

- Russian Airborne Troops

- Naval Infantry (Russia)

- Awards and emblems of the Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation

References

- ↑ International Institute for Strategic Studies: The Military Balance 2015, p.186

- ↑ https://www.euractiv.com/section/europe-s-east/news/ukraine-with-minsk-stalled-russia-sanctions-must-continue/

- ↑ Главнокомандующий Сухопутными войсками Олег Салюков. Биография (in Russian). ITAR TASS. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- ↑ "Official website [Translated by Babelfish and amended for readability].". Russian Ministry of Defence. Archived from the original on January 9, 2007. Retrieved 28 October 2006.

- 1 2 International Institute for Strategic Studies (1992). The Military Balance 1992–3. London: Brassey's. p. 89.

- ↑ International Institute for Strategic Studies (1995). The Military Balance 1995–96. London: Brassey's. p. 102.

- 1 2 Muraviev, Alexey D.; Austin, Greg (2001). The Armed Forces of Russia in Asia. Armed Forces of Asia (Illus. ed.). London: I. B. Tauris. p. 257. ISBN 978-1-86064-505-1.

- 1 2 Orr, Michael (June 1998). "The Russian Armed Forces as a factor in Regional Stability" (PDF). Conflict Studies Research Centre: 2.

- 1 2 Baev, Pavel (1996). The Russian Army in a Time of Troubles. International Peace Research Institute. Oslo: Sage Publications. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-7619-5187-2.

- ↑ Dick, Charles (November 1993). "Russian Views on Future War—Part 3". Jane's Intelligence Review. IHS Jane's: 488. ISSN 1350-6226.

- ↑ Arbatov, Alexei (Spring 1998). "Military Reform in Russia: Dilemmas, obstacles, and prospects". International Security. 22 (4): 112. doi:10.2307/2539241. ISSN 0162-2889.

- ↑ Arbatov, 1998, p. 113

- ↑ Orr, Michael (January 2003). The Russian Ground Forces and Reform 1992–2002 (Report). Conflict Studies Research Centre. pp. 2–3. D67.

- 1 2 McNair Paper 34, The Russian Military's Role in Politics (Report). January 1995. Archived from the original on 2008-01-14.

- ↑ Finch, Raymond C., III, MAJ. Why the Russian Military Failed in Chechnya (Report). Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Foreign Military Studies Office.

- ↑ Herspring, Dale (July 2006). "Undermining Combat Readiness in the Russian Military" (PDF). Armed Forces & Society. 32 (4): 512–531. doi:10.1177/0095327X06288030. ISSN 0095-327X. [citing Blandy, C. W. (January 2000). Chechnya: Two Federal Interventions: An interim comparison and assessment (Report). Conflict Studies Research Centre. p. 13. P29.]

- ↑ Scott, Harriet Fast; Scott, William F. (2002). Russian Military Directory. p. 328.

- ↑ Trenin, Dmitri V.; Malashenko, Aleksei V. (2004). Russia's Restless Frontier. Washington DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. p. 106. ISBN 0-87003-204-6.

- ↑ Orr, Michael (2000). Better or Just Not So Bad? An evaluation of Russian combat performance in the Second Chechen War (PDF). Conflict Studies Research Centre. p. 82. P31.

- ↑ Orr (2000), p. 87

- ↑ Orr (2000), p. 88–90

- ↑ "Chechnya and the North Caucasus". AlertNet. Thomson Reuters Foundation. 4 November 2007. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- ↑ "Top Russian general sacked". BBC News World Edition (Europe). BBC. 18 December 2002. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- ↑ "Russia 'ends Chechnya operation". BBC News. BBC. 16 April 2009.

- ↑ Parchomenko, Walter (Winter 1999–2000). "The State of Russia's Armed Forces and Military Reform". Parameters: the U.S. Army's senior professional journal: 98–110. ISSN 0031-1723.

- ↑ Armeiskii Sbornik, Aug 1998, FBIS-UMA-98-340, 6 Dec 98 'Russia: New Look of Ground Troops'.

- ↑ Krasnaya Zvezda 28 January and 9 February 1999, in Austin & Muraviev, 2000, p. 268, and M.J. Orr, 1998, p. 3

- ↑ Muraviev and Austin, 2001, p. 259

- 1 2 Orr, 2003, p. 6

- 1 2 The World Factbook (2006 ed.). ISBN 0-16-076547-1.

- ↑ International Institute for Strategic Studies (2000). The Military Balance, 2000–2001. Oxford University Press. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-19-929003-1. ISSN 0459-7222.

- ↑ International Institute for Strategic Studies (2001). The Military Balance, 2001-2002 (Pap/Map ed.). International Institute for Strategic Studies. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-19-850979-0. ISSN 0459-7222.

- ↑ International Institute for Strategic Studies. The Military Balance. International Institute for Strategic Studies. Russia. ISSN 0459-7222. (recent editions)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Goltz, Alexander (2004). "Military Reform in Russia and the Global War Against Terrorism". Journal of Slavic Military Studies. Routledge. 17: 30–34. doi:10.1080/13518040490440647. ISSN 1351-8046.

- ↑ "Russia's public sector wages to rise 30% from Dec. 1 - PM Putin". RIA Novosti. RIA Novosti. RIA Novosti. 29 June 2008. Russia. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Giles, Keir (May 2007). Military Service in Russia: No New Model Army (PDF). Conflict Studies Research Centre.

- 1 2 Giles, Keir (October 2006). Where Have All The Soldiers Gone? Russian military manpower plans versus demographic reality (Report). Conflict Studies Research Centre.

- ↑ "How are the mighty fallen". The Economist. 2008-09-18. Retrieved 2008-09-21. (subscription required)

- ↑ Yegorov, Ivan (18 December 2008). "Serdyukovґs radical reform". Russia Beyond the Headlines. Rossiyskaya Gazeta. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- ↑ "Russia creates 20 motorized infantry brigades". RIA Novosti. RIA Novosti. RIA Novosti. 20 March 2009. Russia. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- ↑ Russia's military reform still faces major problems

- ↑ Russia Reshapes Army Structure to U.S.-Style Brigades, October 5, 2009

- ↑ Kormiltsev was a Colonel General when he became Commander-in-Chief of the Ground Forces, but after about two years in the position was promoted to General of the Army in 2003. Profile via FBIS, Kormiltsev Biography, accessed September 2007

- ↑ "Putin Fires Military Commander Over Bribe Charges", The Moscow Times (20 Dec 2013)

- ↑ "Главкома Сухопутных войск винят в коррупции", dni.ru (Russian) (19 Dec 2013)

- ↑ Scott and Scott, Russian Military Directory 2004, p. 118

- ↑ Babakin, Alexander (August 20–26, 2004). "Approximate Composition and Structure of the Armed Forces After the Reforms". Nezavisimoye Voyennoye Obozreniye [Independent Military Review] (31).

- ↑ IISS Military Balance, various issues

- ↑ International Institute for Strategic Studies (2007). Christopher Langton, ed. The Military Balance, 2007 (Revised ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-1-85743-437-8. ISSN 0459-7222.

- ↑ V.I. Feskov et al. 2004 is the source for the designations, while vad777's website is the source for their disbandment. See also Michael Holm, 12th Artillery Division and http://www.ww2.dk/new/army/arty/15gvad.htm

- ↑ Butowsky, p. 81

- ↑ Butowsky, p. 83

- ↑ Moscow Defense Brief #2, 2010 page 23

- ↑ Moscow Defense Brief #1, 2011 page 15

- 1 2 Ria Novosti 2010 Archived February 28, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Milenin, Andrei (20 September 2016). "Александр Дворников назначен командующим войсками ЮВО" [Aleksandr Dvornikov appointed commander of the Southern Military District]. Isvestia (in Russian). Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ↑ Ilyin, Igor. "Сергей Севрюков принял штандарт командующего 49-й общевойсковой армией" [Sergey Sevryukov accepted command of the 49th Combined Arms Army]. www.stapravda.ru (in Russian). Stavropol Pravda. Retrieved 2016-02-25.

- ↑ International Institute for Strategic Studies (2006). Christopher Langton, ed. The Military Balance 2006 (106 ed.). Routledge. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-85743-399-9. ISSN 0459-7222.

- ↑ Also an IISS estimate.

- ↑ Schofield, Carey (1991). Inside the Soviet Army. London: Headline. pp. 67–70. ISBN 978-0-7472-0418-3.

- ↑ Suvorov, Viktor (1982). Inside the Soviet Army. London: Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 978-0-241-10889-5.(gives the figure of six months with a training division)

- ↑ Odom, William E. (1998). The Collapse of the Soviet Military. Yale University Press. p. 43. ISBN 0-300-07469-7.

- ↑ Odom, p. 40–41

- ↑ Odom, p. 42

- ↑ Quartly, Alaan (8 March 2003). "Miss Shooting Range crowned". BBC News. (It is quite possible that the BBC reporter became confused between the Army (Ground Forces) and the entire Armed Forces, given their usual title in Russian of Armiya.)

- ↑ Matthews, Jennifer G. (Fall–Winter 2000). "Women in the Russian Armed Forces—A Marriage of Convenience?". Minerva: Quarterly report on women and the military. 18 (3/4). ISSN 1573-1871.

- ↑ IISS, The Military Balance 2006, p. 147

- ↑ International Institute for Strategic Studies (2005). The Military Balance, 2004–2005. Routledge. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-19-856622-9. ISSN 0459-7222.

- ↑ Orr (2003), p. 12

- ↑ Jane's World Armies (18): 564. December 2005. ISBN 978-0-7106-1389-9. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - 1 2 3 4 Orr (2003), p. 10

- ↑ IISS 2006, p. 155

- ↑ Austin and Muraviev, 2001, p. 277–278

- ↑ Baranov, Nikolai, "Weapons must serve for a long while", Armeiskii sbornik, March 1998, no. 3, p. 66–71, cited in Austin and Muraviev, 2001, p. 278. See also Mil Bal 95/96, p. 110

- ↑ "Russia's new main battle tank to enter service 'after 2010'". RIA Novosti. RIA Novosti. RIA Novosti. 10 July 2008.

- ↑ "Russia's Military Budget 2004 - 2007 | Russian Arms, Military Technology, Analysis of Russia's Military Forces". Warfare.ru. Retrieved 2008-09-10.

- ↑ Tank database, warfare.ru - Russian Military Analisis. Retrieved on 1 September 2008.

- ↑ T-72, warfare.ru - Russian Military Analysis. Retrieved on 8 January 2014.

- ↑ T-80, warfare.ru - Russian Military Analysis. Retrieved on 8 January 2014.

- ↑ IFV & APC database, warfare.ru - Russian Military Analysis. Retrieved on 1 September 2008.

- ↑ BMP-1, warfare.ru - Russian Military Analysis. Retrieved on 8 January 2014.

- ↑ BMP-2, warfare.ru - Russian Military Analysis. Retrieved on 8 January 2014.

- ↑ MT-LB, warfare.ru - Russian Military Analysis. Retrieved on 2 January 2013.

- ↑ MT-LB, warfare.ru - Russian Military Analysis. Retrieved on 9 January 2014.

- ↑ Artillery, warfare.ru - Russian Military Analysis. Retrieved on 2 January 2013.

- ↑ Artillery database, warfare.ru - Russian Military Analysis. Retrieved on 1 September 2008.

- ↑ Multiple Rocket Launchers database, warfare.ru - Russian Military Analysis. Retrieved on 2 January 2013.

- ↑ SAM systems, warfare.ru - Russian Military Analysis. Retrieved on 2 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 Odom (1998), p. 302

- ↑ Chronology of events—Rodionov dismisses commander of ground forces and then cancels visit to United States (Report). Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. 4 December 1996. Archived from the original on 2007-03-19. Retrieved September 2008. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Turbiville, Graham H. "Mafia in Uniform: The criminalization of the Russian Armed Forces".

- ↑ Galeotti, Mark. "Moscow's Armed Forces: a city's balance of power". Jane's Intelligence Review: 52. ISSN 1350-6226.

- ↑ "No solution to hideous army hazing in Russia", Pravda (25 March 2011)

- ↑ "Serving to death in the Russian army", Russia Today (30 April 2011)

- ↑ "Extremism and violence on the rise among servicemen – Military Prosecutor", Russia Today (25 March 2011)

- ↑ "Violent Crimes In Russian Army Increase", Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (27 March 2011)

- ↑ http://russiandefpolicy.wordpress.com/2011/07/26/latest-on-sulim-and-premium-pay-extortion/

- ↑ "Crime reportedly flourishes in Russian army", Deutsche Welle (18 August 2012)

- ↑ "Corruption Up 450% in a Year in Russian Military – Prosecutors ", RIA Novosti (11 July 2013)

Bibliography

- Arbatov, Alexei (1998). "Military Reform in Russia: Dilemmas, Obstacles, and Prospects". International Security. The MIT Press. 22 (4): 83. doi:10.2307/2539241. JSTOR 2539241.

- Austin, Greg & Muraviev, Alexey D. (2001). The Armed Forces of Russia in Asia. Tauris. ISBN 1-86064-485-6.

- Babakin, Alexander (August 20–26, 2004). "Approximate Composition and Structure of the Armed Forces After the Reforms" (31). Nezavisimoye Voyennoye Obozreniye (Independent Military Review).

- Baev, Pavel (1996). The Russian Army in a Time of Troubles. Oslo: International Peace Research Institute. ISBN 0-7619-5187-3.

- Baumgardner, Neil. "Russian Armed Forces Order of Battle". Archived from the original on 2009-10-23.

- Butowsky, Piotr (July 2007). "Russia Rising". Air Forces Monthly.

- Central Intelligence Agency (2006). "World Fact Book".

- Dick, Charles. (November 1993). "Russian Views on Future War, Part 3". Jane's Intelligence Review.

- "How are the mighty fallen". The Economist. 2005-06-30.

- Fes'kov, V.I.; Golikov, V.I. & K.A. Kalashnikov (2004). The Soviet Army In The Years Of The Cold War 1945–1991. Tomsk University Publishing House. ISBN 5-7511-1819-7.

- Finch, Raymond C. "Why the Russian Military Failed in Chechnya". Fort Leavenworth, KS: Foreign Military Studies Office.

- Galeotti, Mark (February 1997). "Moscow's armed forces: a city's balance of power". Jane's Intelligence Review.

- Giles, Keir (May 2007). "Military Service in Russia: No New Model Army" (PDF). CSRC.

- Golts, Alexander (2004). "Military Reform in Russia and the Global War Against Terrorism". Journal of Slavic Military Studies. 17: 29. doi:10.1080/13518040490440647.

- Herspring, Dale (July 2006). "Undermining Combat Readiness in the Russian Military". 32 (4). Armed Forces & Society.

- "The Military Balance". International Institute for Strategic Studies.

- Lenskii, A.G. & Tsybin, M.M. (2001). The Soviet Ground Forces in the Last Years of the USSR. St Petersburg: B&K Publishers.

- Lukin, Mikhail & Stukalin, Aleksander (14 May 2005). "Vsya Rossiyskaya Armiya". Moscow: Kommersant-Vlast.

- James H. Brusstar & Ellen Jones (January 1995). "McNair Paper 34, The Russian Military's Role in Politics".

- Odom, William E. (1998). The Collapse of the Soviet Military. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07469-7.

- Orr, Michael (June 1998). "The Russian Armed Forces as a factor in Regional Stability". CSRC.

- Orr, Michael (2000). "Better or Just Not So Bad? An Evaluation of Russian Combat Performance in the Second Chechen War". CSRC.

- Orr, Michael (2003). "The Russian Ground Forces and Reform 1992–2002".

- Parchomenko, Walter (1999–2000). "The State of Russia's Armed Forces and Military Reform". Parameters (Journal of the US Army War College).

- Quartly, Alan (8 March 2003). "Miss Shooting Range crowned". BBC News.

- Robinson, Colin (2005). "The Russian Ground Forces Today: A Structural Status Examination". Journal of Slavic Military Studies. 18 (2): 189. doi:10.1080/13518040590944421.

- Schofield, Carey (1991). Inside the Soviet Army. London: Headline. ISBN 0-7472-0418-7.

- Scott, Harriet Fast & Scott, William F. Russian Military Directories 2002 & 2004

- Suvorov, Viktor (1982). Inside the Soviet Army. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-586-05978-4.

- Turbiville, Graham H. (1995). Mafia in Uniform: The Criminalisation of the Russian Armed Forces. Fort Leavenworth: U.S. Army Foreign Military Studies Office.