Sarahsaurus

| Sarahsaurus Temporal range: Early Jurassic | |

|---|---|

| |

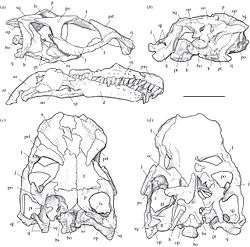

| Illustration of the skull in multiple views | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Order: | Saurischia |

| Suborder: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Clade: | †Massopoda |

| Genus: | †Sarahsaurus Rowe, Sues & Reisz, 2011 |

| Species: | †S. aurifontanalis |

| Binomial name | |

| Sarahsaurus aurifontanalis Rowe, Sues & Reisz, 2011 | |

Sarahsaurus is a genus of basal sauropodomorph dinosaur which lived during the lower Jurassic period in what is now northeastern Arizona, United States.[1]

Discovery and naming

Sarahsaurus is known from a nearly complete articulated holotype skeleton referred to as TMM 43646-2, another partial skeleton known as TMM 43646-3, and a nearly complete but poorly preserved skull known as MCZ 8893.[1] This last specimen was previously described and referred to as Massospondylus sp.[2]

Sarahsaurus was first described by Timothy B. Rowe, Hans-Dieter Sues and Robert R. Reisz in 2011 and the type species is Sarahsaurus aurifontanalis. The generic name honours Sarah Butler, and sauros (Greek), for "lizard". The specific name is derived from aurum (Latin), "gold", and fontanalis (Latin), "of the spring" in reference to Gold Spring, Arizona, where the holotype was found. Sarahsaurus is the fourth basal sauropodomorph dinosaur to have been identified in North America. (The other three are Anchisaurus and Ammosaurus from the Early Jurassic of the Connecticut River Valley, and Seitaad of the later Navajo Sandstone of Early Jurassic Utah.) It is thought to have appeared through a dispersal event that originated in South America and was separate from those of the other two sauropodomorphs.[1] The animal is notable for possessing very large, powerful hands, suggesting that it was an omnivore.[3]

Classification

In a cladistic analysis, presented by Apaldetti and colleagues in November 2011, Sarahsaurus was found to be most closely related to Ignavusaurus within Massopoda. Their group was found to be intermediate between plateosaurids and massospondylids, being more derived than the former and more primitive than the latter.[4]

| Plateosauria |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

Paleoecology

Habitat

All specimens of Sarahsaurus were collected from the Early Jurassic Kayenta Formation near Gold Spring, Arizona.[1] A definitive radiometric dating of this formation has not yet been made, and the available stratigraphic correlation has been based on a combination of radiometric dates from vertebrate fossils, magnetostratigraphy and pollen evidence.[5] It has been surmised that the Kayenta Formation was deposited during the Sinemurian and Pliensbachian stages of the Early Jurassic Period or approximately 199 to 182 million years ago.[6] The Kayenta Formation is part of the Glen Canyon Group that includes formations not only in northern Arizona but also parts of southeastern Utah, western Colorado, and northwestern New Mexico. The formation was primarily deposited by rivers. During the Early Jurassic period, the land that is now the Kayenta Formation experienced rainy summers and dry winters. By the Middle Jurassic period it was being encroached upon from the north by a sandy dune field that would become the Navajo Sandstone.[7] The animals here were adapted to a seasonal climate and abundant water could be found in streams, ponds and lakes.

Paleofauna

Sarahsaurus shared its paleoenvironment with other dinosaurs, such as several theropods including Dilophosaurus, Kayentavenator,[8] Megapnosaurus kayentakatae, the "Shake N Bake" theropod, and the armored dinosaurs Scelidosaurus and Scutellosaurus. The Kayenta formation has produced that remains of three coelophysoid taxa of different body size,which represents the most diverse ceratosaur fauna yet known.[9] The Kayenta Formation has yielded a small but growing assemblage of organisms.[10] Vertebrates present in the Kayenta Formation at the time of Saharasaurus included hybodont sharks, bony fish known as osteichthyes, lungfish, salamanders, the frog Prosalirus, the caecilian Eocaecilia, the turtle Kayentachelys, a sphenodontian reptile, various lizards. Also present were, the synapsids Dinnebiton, Kayentatherium, and Oligokyphus.,[11] several early crocodylomorphs including Calsoyasuchus, Eopneumatosuchus, Kayentasuchus, and Protosuchus, and the pterosaur Rhamphinion.[10][11][12][13] The possible presence of the early true mammal Dinnetherium, and a haramyid mammal has also been proposed, based on fossil finds. Vertebrate trace fossils from this area included coprolites[14] and the tracks of therapsids, lizard-like animals, and dinosaurs, which provided evidence that these animals were also present.[15] Non-vertebrates in this ecosystem included microbial or "algal" limestone,[14] freshwater bivalves, freshwater mussels and snails,[7] and ostracods.[16] The plant life known from this area included trees that became preserved as petrified wood.[12]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Timothy B. Rowe, Hans-Dieter Sues and Robert R. Reisz (2011). "Dispersal and diversity in the earliest North American sauropodomorph dinosaurs, with a description of a new taxon". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 278 (1708): 1044–1053. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.1867. PMC 3049036

. PMID 20926438.

. PMID 20926438. - ↑ Attridge, J.; A.W. Crompton and Farish A. Jenkins, Jr. (1985). "The southern Liassic prosauropod Massospondylus discovered in North America". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 5 (2): 128–132. doi:10.1080/02724634.1985.10011850. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - ↑ http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2010/10/101006-new-dinosaur-north-america-science/

- ↑ Cecilia Apaldetti, Ricardo N. Martinez, Oscar A. Alcober and Diego Pol (2011). Claessens, Leon, ed. "A New Basal Sauropodomorph (Dinosauria: Saurischia) from Quebrada del Barro Formation (Marayes-El Carrizal Basin), Northwestern Argentina". PLoS ONE. 6 (11): e26964. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026964. PMC 3212523

. PMID 22096511.

. PMID 22096511. - ↑ J. M. Clark and D. E. Fastovsky. 1986. Vertebrate biostratigraphy of the Glen Canyon Group in northern Arizona. The Beginning of the Age of the Dinosaurs: Faunal change across the Triassic-Jurassic boundary, N. C. Fraser and H.-D. Sues (eds.), Cambridge University Press 285–301

- ↑ Padian, K (1997) Glen Canyon Group In: Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs, edited by Currie, P. J., and Padian, K., Academic Press.

- 1 2 Harshbarger, J. W.; Repenning, C. A.; Irwin, J. H. (1957). Stratigraphy of the uppermost Triassic and the Jurassic rocks of the Navajo country. Professional Paper. 291. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Geological Survey.

- ↑ Gay, R. 2010. Kayentavenator elysiae, a new tetanuran from the early Jurassic of Arizona. Pages 27–43 in Gay, R. Notes on early Mesozoic theropods. Lulu Press (on-demand online press).

- ↑ Tykoski, R. S., 1998, The Osteology of Syntarsus kayentakatae and its Implications for Ceratosaurid Phylogeny: Theses, The University of Texas, December 1998.

- 1 2 Lucas, S. G.; Heckert, A. B.; Tanner, L. H. (2005). "Arizona's Jurassic fossil vertebrates and the age of the Glen Canyon Group". In Heckert, A. B.; Lucas, S. G. Vertebrate paleontology in Arizona. Bulletin. 29. Albuquerque, NM: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 95–104.

- 1 2 Jenkins, F. A., Jr., Crompton, A. W., and Downs, W. R. 1983. Mesozoic mammals from Arizona: new evidence in mammalian evolution. Science 222(4629):1233–1235.

- 1 2 Jenkins, F. A., Jr. and Shubin, N. H. 1998. Prosalirus bitis and the anuran caudopelvic mechanism. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 18(3):495–510.

- ↑ Curtis, K., and Padian, K. 1999. An Early Jurassic microvertebrate fauna from the Kayenta Formation of northeastern Arizona: microfaunal change across the Triassic-Jurassic boundary. PaleoBios 19(2):19–37.

- 1 2 Luttrell, P. R., and Morales, M. 1993. Bridging the gap across Moenkopi Wash: a lithostratigraphic correlation. Aspects of Mesozoic geology and paleontology of the Colorado Plateau. Pages 111–127 in Morales, M., editor. Museum of Northern Arizona, Flagstaff, AZ. Bulletin 59.

- ↑ Hamblin, A. H., and Foster, J. R. 2000. Ancient animal footprints and traces in the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, south-central Utah. Pages 557–568 in Sprinkel, D. A., Chidsey, T. C., Jr., and Anderson, P. B. editors. Geology of Utah's parks and monuments. Utah Geological Association, Salt Lake City, UT. Publication 28.

- ↑ Lucas, S. G., and Tanner L. H. 2007. Tetrapod biostratigraphy and biochronology of the Triassic-Jurassic transition on the southern Colorado Plateau, USA. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 244(1–4):242–256.