Coprolite

| Part of a series on |

| Paleontology |

|---|

|

|

Organs and processes |

|

History of paleontology |

|

Branches of paleontology |

|

Paleontology Portal Category |

_from_South_Carolina%2C_USA..jpg)

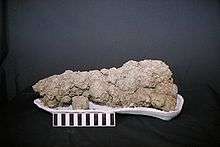

A coprolite is fossilized feces. Coprolites are classified as trace fossils as opposed to body fossils, as they give evidence for the animal's behaviour (in this case, diet) rather than morphology. The name is derived from the Greek words κόπρος (kopros, meaning "dung") and λίθος (lithos, meaning "stone"). They were first described by William Buckland in 1829. Prior to this they were known as "fossil fir cones" and "bezoar stones". They serve a valuable purpose in paleontology because they provide direct evidence of the predation and diet of extinct organisms.[1] Coprolites may range in size from a few millimetres to over 60 centimetres.

Coprolites, distinct from paleofaeces, are fossilized animal dung. Like other fossils, coprolites have had much of their original composition replaced by mineral deposits such as silicates and calcium carbonates. Paleofaeces, on the other hand, retain much of their original organic composition and can be reconstituted to determine their original chemical properties, though in practice the term coprolite is also used for ancient human faecal material in archaeological contexts.[2] In the same context, there are the urolites, erosions caused by evacuation of liquid wastes and nonliquid urinary secretions.

Initial discovery

The fossil hunter Mary Anning had noticed that "bezoar stones" were often found in the abdominal region of ichthyosaur skeletons found in the Lias formation at Lyme Regis. She also noted that if such stones were broken open they often contained fossilized fish bones and scales as well as sometimes bones from smaller ichthyosaurs. It was these observations by Anning that led the geologist William Buckland to propose in 1829 that the stones were fossilized feces and named them coprolites. Buckland also suspected that the spiral markings on the fossils indicated that ichthyosaurs had spiral ridges in their intestines similar to those of modern sharks, and that some of these coprolites were black with ink from swallowed belemnites.[3]

Research value

By examining coprolites, paleontologists are able to find information about the diet of the animal (if bones or other food remains are present), such as whether it was a herbivorous or carnivorous, and the taphonomy of the coprolites, although the producer is rarely identified unambiguously, especially with more ancient examples.[4] In one example these fossils can be analyzed for certain minerals that are known to exist in trace amounts in certain species of plant that can still be detected millions of years later.[5] In another example, the existence of human proteins in coprolites can be used to pinpoint the existence of cannibalistic behavior in an ancient culture.[6] Parasite remains found in human and animal coprolites have also shed new light on questions of human migratory patterns, the diseases which plagued ancient civilizations, and animal domestication practices in the past (see archaeoparasitology and paleoparasitology).

Recognizing coprolites

The recognition of coprolites is aided by their structural patterns, such as spiral or annular markings, by their content, such as undigested food fragments, and by associated fossil remains. The smallest coprolites are often difficult to distinguish from inorganic pellets or from eggs. Most coprolites are composed chiefly of calcium phosphate, along with minor quantities of organic matter. By analyzing coprolites, it is possible to infer the diet of the animal which produced them.

Coprolites have been recorded in deposits ranging in age from the Cambrian period to recent times and are found worldwide. Some of them are useful as index fossils, such as Favreina from the Jurassic period of Haute-Savoie in France.

Some marine deposits contain a high proportion of fecal remains. However, animal excrement is easily fragmented and destroyed, so usually has little chance of becoming fossilized.

Coprolite mining

In 1842 the Rev John Stevens Henslow, a professor of Botany at St John's College, Cambridge, discovered coprolites just outside Felixstowe in Suffolk in the villages of Trimley St Martin,[7] Falkenham and Kirton[8] and investigated their composition. Realising their potential as a source of available phosphate once they had been treated with sulphuric acid, he patented an extraction process and set about finding new sources.[9] Very soon, coprolites were being mined on an industrial scale for use as fertiliser due to their high phosphate content. The major area of extraction occurred over the east of England, centred on Cambridgeshire and the Isle of Ely[10][11] with its refining being carried out in Ipswich by the Fison Company.[11] There is a Coprolite Street near Ipswich docks where the Fisons works once stood.[12] The industry declined in the 1880s[11][13] but was revived briefly during the First World War to provide phosphates for munitions.[10] A renewed interest in coprolite mining in the First World War extended the area of interest into parts of Buckinghamshire as far west as Woburn Sands.[9]

See also

| Look up coprolite in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Notes

- ↑ "coprolites - Definitions from Dictionary.com".

- ↑ Poinar, H. N., S. Fiedel, C. E. King, A. M. Devault, K. Bos, M. Kuch, and R. Debruyne1 ; 2009 Comment on “DNA from Pre-Clovis Human Coprolites in Oregon, North America.” Science 325(5937):148. ; P. Goldberg, F. Berna and R.I. Macphail ; 2009 Comment on “DNA from Pre-Clovis Human Coprolites in Oregon, North America.” Science 325(5937): 148. ; Gilbert, T., D. L. Jenkins, A. Götherstrom, N. Naveran, J. J. Sanchez, M. Hofreiter, P. F. Thomsen, J. Binladen, T. F.G. Higham, R. M. Yohe II, R. Parr, L. S. Cummings, E Willerslev ; 2008 DNA from Pre-Clovis Human Coprolites in Oregon, North America. Science. 320(5877):786-789.

- ↑ Rudwick, Martin Worlds Before Adam: The Reconstruction of Geohistory in the Age of Reform pp. 154-155.

- ↑ "The Wonders of Dinosaur Dung - Sepia Mutiny".

- ↑ "Dung Fossils Suggest Dinosaurs Ate Grass".

- ↑ "Biochemical evidence of cannibalism at a prehistoric Puebloan site in southwestern Colorado, Nature, 407, 74-78 (7 September 2000)".

- ↑ Trimley St Martin and the Coprolite Mining Rush, Beridge Eve, 2004 Archived October 8, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ (Corpolites in ) Kirton, Suffolk

- 1 2 The Origins and Development of the British Coprolite Industry, Bernard O O'connor, The Bulletin of the Peak District Mines Historical Society, Vol 14, No. 5, Summer 2001

- 1 2 "Coprolite Mining in Cambridgeshire" (PDF).

- 1 2 3 "Cambridgeshire - The Coprolite Mining Industry".

- ↑ "Coprolite Street".

- ↑ "Trimley St. Martin and the Coprolite Mining Rush" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 5, 2012.

References

- Spencer, P. K. (1993). "The "coprolites" that aren't: the straight poop on specimens from the Miocene of southwestern Washington State". Ichnos. 2 (3): 1–6. doi:10.1080/10420949309380097.

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Unsigned. (1911). "Coprolites". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 111–112.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Unsigned. (1911). "Coprolites". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 111–112.