Simon of Trent

| Saint Simon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

1472 Trento, Italy |

| Died |

March 21, 1475 Trent, Prince-Bishopric of Trent |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church |

| Canonized | 1575 (approximate)[1] |

| Feast | March 24 |

| Attributes | Youth, martyrdom |

| Patronage | Children, kidnap victims, torture victims |

| Controversy | Blood libel |

Catholic cult suppressed | After the Congregation |

Simon of Trent (German: Simon Unverdorben ("Simon Immaculate"); Italian: Simonino di Trento); also known as Simeon; (1472 – March 21, 1475) was a boy from the city of Trent, Prince-Bishopric of Trent, whose disappearance and murder was blamed on the leaders of the city's Jewish community, based on his dead body allegedly being found in the cellar of a Jewish family's house.[2]

Events

The story of Simon of Trent belongs to the reign of Prince-Bishop Johannes IV Hinderbach, an Austrian noble, under the jurisdiction of Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III. Shortly before Simon went missing, Bernardine of Feltre, an itinerant Franciscan preacher, had delivered a series of sermons in Trent in which he vilified the local Jewish community. When Simon went missing around Easter, 1475, according to his story, the Jews had drained him of his blood for use in baking their Passover matzo and for occult rituals that they practiced in private (q.v. blood libel).

According to historian Ronnie Po-chia Hsia:

- "On Easter Sunday 1475, the dead body of a 2-year-old Christian boy named Simon was found in the cellar of a Jewish family's house in Trent, Italy. Town magistrates arrested eighteen Jewish men and five Jewish women on the charge of ritual murder — the killing of a Christian child in order to use his blood in Jewish religious rites. In a series of interrogations that involved liberal use of judicial torture, the magistrates obtained the confessions of the Jewish men. Eight were executed in late June, and another committed suicide in jail".:[2]

The exact place where the boy's body was found seems to be unclear. According to the Catholic historian Cölestin Wolfsgrüber, the body was found in a ditch.[3]

The consequences, however, are well documented. The entire Jewish community (both men and women) were arrested and forced to confess under torture. Fifteen of them, including Samuel, the head of the community, were sentenced to death and burnt at the stake. The Jewish women accused as accomplices were tortured, but freed from prison in 1478 due to papal intervention. The case at Trent also inspired accusations of ritual murder against Jews throughout the surrounding regions.

Pope Sixtus IV commanded Bishop Hinderbach on August 3 to again suspend proceedings, until the arrival of the papal representative, Bishop Giovanni Battista dei Giudici of Ventimiglia, who, jointly with the Bishop of Trent, would conduct the investigation. After making an investigation, the papal agent denied the martyrdom of the child Simon and disputed the occurrence of a miracle at his grave. When Bishop Dei Giudici demanded the immediate release of the Jews he was denounced by Hinderbach and assailed by the mob, and withdrew to Rovereto. Thence, he summoned the bishop and the podestà to answer for their conduct. Instead of appearing, Bishop Hinderbach answered by a circular, directed to all churchmen describing the martyrdom of Simon, justifying his own share in the proceedings, and denouncing the work of the Bishop of Ventimiglia. While the papal commissary was taking Enzelin, the supposed actual murderer, a prisoner to Rome for trial, the Bishop of Trent and the podestà continued their proceedings against the Jews, several of whom they executed.

Pope Sixtus appointed a commission of six cardinals to investigate the proceedings. The head of the commission was a close friend of Bernardinus, and on June 20, 1478, the commission concluded that the trial had been conducted in keeping with legal procedures.

Centuries later, historian Ariel Toaff, in his book Pasque Di Sangue (Passovers of Blood), hypothesized that there may be some historical truth[4] to the accusations in Trent. The book was heavily criticized for giving credence to testimony obtained during torture and was pulled from circulation and redacted by its author.[5]

Veneration

Meanwhile, Simon became the focus of attention for the local Catholic Church. The local bishop, Hinderbach of Trent, tried to have Simon canonized, producing a large body of documentation of the event and its aftermath.[6] Over one hundred miracles were directly attributed to Saint Simon within a year of his disappearance, and his cult spread across Italy, Austria and Germany. However, there was initial skepticism and Pope Sixtus IV sent the Bishop of Ventimiglia, a learned member of the Dominican Order, to investigate.[7] The veneration was restored in 1588 by the Franciscan Pope Sixtus V. Simon was eventually considered a martyr and a patron of kidnap and torture victims. His entry in the old Roman Martyrology for March 24 read: Tridénti pássio sancti Simeónis púeri, a Judǽis sævíssime trucidáti, qui multis póstea miráculis coruscávit. ("At Trent, the martyrdom of the boy St. Simeon, who was barbarously murdered by the Jews, but who was afterwards glorified by many miracles.")[8]

In 1758, Cardinal Ganganelli (later Pope Clement XIV, 1769-1774) prepared a legal memorandum which, to the exclusion of all other allegations of ritual murders of infants which records were thoroughly made available to him, expressly admitted as proven only two: that of Simon of Trent and that of Andrea of Rinn. At the same time, he remarkably extols the glories and accomplishments of the Jewish people across history, writing that the murder of Simon of Trent does not suffice to injure the reputation of the entire Jewish people. [9]

Pope Paul VI, for pastoral reasons, removed Simon from the Roman Martyrology in 1965. Simon of Trent does not appear in the new Roman Martyrology of 2000, nor on any modern Catholic calendar.

In summary, the Catholic Church never canonized, viz. "infallibly" declared Simon of Trent to be a saint. His "cultus" was only approved by the Popes for local public liturgical observance ("beatification") within the Diocese of Trent. Pope Benedict XIV himself states this in his Apostolic Letter dated 22 February 1755 addressed to Fr. Benedetto Vetrani, Promoter of Faith.[10]

Image gallery

Portrait of St Simon of Trent, 1607, etching, 28.7 x 21 cm

Portrait of St Simon of Trent, 1607, etching, 28.7 x 21 cm- Altobello Melone, Simon of Trent, ca.1521, oil on panel, Castello del Buonconsiglio, Trent (Italy)

- Unknown painter, Ex voto; fresco, end of the 15th century, church of Santa Maria Annunciata, Bienno (BS), Italy

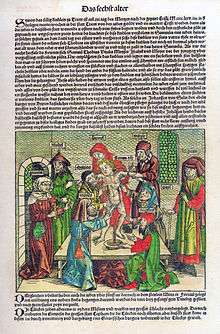

- Incunabulum of Friedrich Creussner, Nuremberg, 1475

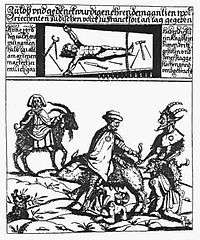

- Simon of Trent's martyred body. Engraving, Nürnberg, around 1479.

Stone medallion with the purported martyrdom scene of Simonino di Trento. Palazzo Salvadori, Trent

Stone medallion with the purported martyrdom scene of Simonino di Trento. Palazzo Salvadori, Trent Illustration in Hartmann Schedel's Weltchronik, 1493

Illustration in Hartmann Schedel's Weltchronik, 1493 Unknown painter, fresco, end of the 15th century, church of Santa Maria Annunciata, Bienno (BS), Italy

Unknown painter, fresco, end of the 15th century, church of Santa Maria Annunciata, Bienno (BS), Italy School of Niklaus Weckmann, 1505–15, polychrome wood, cm. 79 x 109, Museo Diocesano Trentino, Trento (Italy)

School of Niklaus Weckmann, 1505–15, polychrome wood, cm. 79 x 109, Museo Diocesano Trentino, Trento (Italy) Statue of Simon of Trent on the facade of a palace in Trento (situated in "Via del Simonino")

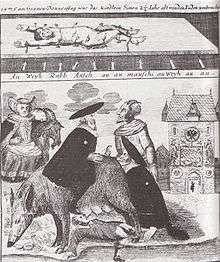

Statue of Simon of Trent on the facade of a palace in Trento (situated in "Via del Simonino") Martyrdom of Simon of Trent above a Judensau.

Martyrdom of Simon of Trent above a Judensau. Martyrdom of Simon of Trent above a Judensau.

Martyrdom of Simon of Trent above a Judensau.

See also

- Little Saint Hugh of Lincoln, 1255.

- William of Norwich

- Werner of Oberwesel

- Andreas Oxner

- Robert of Bury

- Harold of Gloucester

- Prozess gegen die Juden von Trient

References

- ↑ "Simon of Trent". Harvard. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- 1 2 Toaff Controversy

- ↑ Wolfsgrüber, Cölestin. "Trent." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 15. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. Feb. 1, 2014

- ↑ Hannah Johnson, Blood Libel: The Ritual Murder Accusation at the Limit of Jewish History, University of Michigan Press, 2012. pp.132ff. p.132.

- ↑ http://www.jpost.com/International/Historian-gives-credence-to-blood-libel

- ↑ Paul Oskar Kristeller, "The Alleged Ritual Murder of Simon of Trent (1475) and Its Literary Repercussions: a bibliographical study", in: Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research, Vol. 59. (1993), pp. 103-135

- ↑ Jewish Encyclopedia

- ↑ The Roman Martyrology, March 24, retrieved May 8, 2007

- ↑ "Memoire sur la Calomnie du Meurtre Rituel", in Revue des Etudes Juives, Ed. Peeters, 1899, p. 201 et seq.

- ↑ Pope Benedict XIV, Apostolic Letter to Fr. Benedetto Veterani, Promoter of Faith, 22 February 1755, pp. 144-162, in Bullarium

Sources

- R. Po-chia Hsia, Trent 1475: Stories of a Ritual Murder Trial, Yale University, 1992, ISBN 0-300-05106-9

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Simon of Trent. |

- Simon of Trent in the Jewish Encyclopedia.

- Toaff Controversy (Haaretz)