Toki Pona

| Toki Pona | |

|---|---|

| |

| Pronunciation | [toki pona] |

| Created by | Sonja Lang |

| Date | 2001 |

| Setting and usage | testing principles of minimalism, the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis and pidgins |

| Users |

over 100 are said to be fluent (2007)[1] Several dozen with internet chat ability |

| Purpose |

constructed language, combining elements of the subgenres personal language, international auxiliary language and philosophical language |

| Sources | a posteriori language, with elements of English, Tok Pisin, Finnish, Georgian, Dutch, Acadian French, Esperanto, Croatian, Chinese |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

None (mis) |

| Glottolog | None |

Toki Pona is a constructed language, first published as draft on the web in 2001 and then as a complete book and e-book Toki Pona: The Language of Good in 2014. It was designed by translator and linguist Sonja Lang (formerly Sonja Elen Kisa) of Toronto.[2][3]

Toki Pona is a minimal language. Like a pidgin, it focuses on simple concepts and elements that are relatively universal among cultures. Lang designed Toki Pona to express maximal meaning with minimal complexity. The language has 14 phonemes and 120 root words. It is not designed as an international auxiliary language but is instead inspired by Taoist philosophy, among other things.[4]

The language is designed to shape the thought processes of its users, in the style of the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis, in Zen-like fashion.[5]

Authorship

Sonja Lang is a translator (English, French and Esperanto) and linguist living in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.[6] In addition to designing Toki Pona, Lang has translated parts of the Tao Te Ching into English and Esperanto.[7]

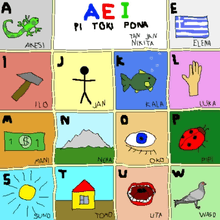

Writing system

Lang officially uses letters of the Latin alphabet to represent the language,[4] with the values they represent in the IPA: p, t, k, s, m, n, l, j, w, a, e, i, o, and u. (That is, j sounds like English y, and the vowels are like those of Spanish.)

Capital letters are only used for personal and place names (see below), not for the first word of a sentence. That is, they mark foreign words, never the 120 Toki Pona roots.

Phonology and phonotactics

Inventory

Toki Pona has nine consonants (/p, t, k, s, m, n, l, j, w/) and five vowels (/a, e, i, o, u/). The first syllable of a word is stressed.[8] There are no diphthongs, long vowels, consonant clusters, or tones.

| Consonants | Labial | Coronal | Dorsal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | |

| Plosive | p | t | k |

| Fricative | s | ||

| Approximant | w | l | j |

Distribution

The statistic vowel spread is fairly typical cross-linguistically. Counting each root once, 32% of vowels are /a/, 25% are /i/, with /e/ and /o/ a bit over 15% each, and 10% are /u/. 20% of roots are vowel initial. The usage frequency in a 10kB sample of texts was slightly more skewed: 34% /a/, 30% /i/, 15% each /e/ and /o/, and 6% /u/.[9]

Of the syllable-initial consonants, /l/ is the most common, at 20% total; /k, s, p/ are over 10%, then the nasals /m, n/ (not counting final N), with the least common, at little more than 5% each, being /t, w, j/.

The high frequency of /l/ and low frequency of /t/ are somewhat unusual among the world's languages. The fact that /l/ occurs in the grammatical particles la, li, ala suggests that its percentage would be even higher in texts; the text-based stats cited above did not specifically consider initial consonants, but indicate that /l/ was about 25%, while /t/ doubled its frequency to just over 10% (/k/, /t/, /m/, /s/, /p/, respectively, ranged over 12% to 9% each, with /n/ unknown, and the semivowels /j/ and /w/ again coming in last at 7% each).

Syllable structure

All syllables are of the form (C)V(N), that is, optional consonant + vowel + optional final nasal, or V, CV, VN, CVN. As in most languages, CV is the most common syllable type, at 75% (counting each root once). V and CVN syllables are each around 10%, while only 5 words have VN syllables (for 2% of syllables). In both the dictionary and in texts, the ratio of consonants to vowels is almost exactly one-to-one.

Most roots (70%) are disyllabic; about 20% are monosyllables and 10% trisyllables. This is a common distribution, and similar to Polynesian.

Phonotactics

The following sequences are not allowed: */ji, wu, wo, ti/, nor may a syllable-final nasal occur before /m/ or /n/ in the same root. Syllables that aren't word-initial must have an initial consonant, though in roots like ijo (from Esperanto io) and suwi (ultimately from English sweet), that might be considered an orthographic convention, with the effect that glottal stop only marks word boundaries. (The sequences /ij/ and /uw/ are no more easily distinguished from simple /i/ and /u/ than the banned */ji/ and */wu/ are.)

Allophony

The nasal at the end of a syllable can be pronounced as any nasal stop, though it is normally assimilated to the following consonant. That is, it typically occurs as an [n] before /t/ or /s/, as an [m] before /p/, as an [ŋ] before /k/, and as an [ɲ] before /j/.

Because of its small phoneme inventory, Toki Pona allows for quite a lot of allophonic variation. For example, /p t k/ may be pronounced [b d ɡ] as well as [p t k], /s/ as [z] or [ʃ] as well as [s], /l/ as [ɾ] as well as [l], and vowels may be either long or short. Both its sound inventory and phonotactics (patterns of possible sound combinations) are found in the majority of human languages and are therefore readily accessible. For example, */ji, wu, wo/ are also impossible in Korean, which is convenient when writing Toki Pona in hangul, which would have no way of writing such syllables (see below).

Syntax

Some basic features of Toki Pona's subject–verb–object syntax are: The word li separates the subject from the predicate; e precedes the direct object; direct object phrases precede prepositional phrases in the predicate; la separates complex adverbs or subclauses from the main sentence.

The language is simple enough that its syntax can be expressed in ten rules: [brackets] enclose optional elements, and *asterisks mark elements which may be repeated.

- Syntactic rules

- 1. A sentence may be

- (a) an interjection

- (b) of the form [sub-clause] [vocative] subject predicate

- (c) of the form [sub-clause] vocative predicate

- (The interjection may be a, ala, ike, jaki, mu, o, pakala, pona, or toki.)

- 2. A sub-clause may be

- (a) [taso] sentence la

- (b) [taso] noun phrase la

- ("If/during sub-clause, then main-clause")

- 3. A [vocative] is of the form

- [noun phrase] o

- 4. A subject is of the form

- (a) mi or sina

- (b) other noun phrase li

(mi mute and sina mute require li to form a predicate.)

- 5. A predicate may be

- (a) simple noun phrase [prepositional phrase]*, or

- (b) verb phrase [prepositional phrase], or

- (c) predicate conjunction predicate (that is, a compound predicate)

- (The conjunction may be anu (or) or li (and). The latter is merely subject li predicate 1 li predicate 2 etc., with the first li dropping out if the subject is mi or sina)

- 6. A noun phrase may be

- (a) noun [modifier]*, or

- (b) simple noun phrase pi (of) noun plus modifier* (if there is a modifier which only applies to the 2nd noun), or

- (c) noun phrase conjunction noun phrase (that is, a compound noun phrase)

- (The conjunction may be anu (or) or en (and). A 'simple' noun phrase is one which does not have a conjunction.)

- 7. A prepositional phrase is of the form

- preposition noun phrase

- 8. A verb phrase may be

- (a) verbal

- (b) modal verbal

- (c) verbalx ala verbalx (both verbals are the same)

- (d) modalx ala modalx plus verbal (both modals are the same)

- (The modal may be kama (coming/future tense), ken (can), or wile (wants to).)

- 9 A verbal may be

- (a) verb [modifier]* (this is an intransitive verb)

- (b) verb [modifier]* plus a direct object* (this is a transitive verb)

- (c) lon or tawa plus a simple noun phrase

- (Some roots may only function as transitive or intransitive verbs.)

- 10. A direct object is of the form

- e simple noun phrase

Some roots are used for grammatical functions (such as those that take part in the rules above), while others have lexical meanings. The lexical roots do not fall into well defined parts of speech; rather, they may generally be used as nouns, verbs, or modifiers, depending on context or their position in a phrase. For example, ona li moku may mean "they ate" or "it is food".

Pronouns

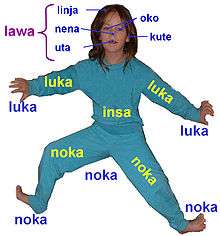

Toki Pona has the basic pronouns mi (first person), sina (second person), and ona (third person).[10]

The above words do not specify number or gender. Thus, ona can mean "he", "she", "it", or "they". In practice, Toki Pona speakers use the phrase mi mute to mean "we". Although less common, ona mute means "they" and sina mute means "you" (plural).

Whenever the subject of a sentence is either of the unmodified pronouns mi or sina, then li is not used to separate the subject and predicate.

Nouns

With such a small root-word vocabulary, Toki Pona relies heavily on noun phrases (compound nouns), where a noun is modified by a following root, to make more complex meanings.[11] A typical example is combining jan (person) with utala (fight) to make jan utala (soldier, warrior). [See 'modifiers' next.]

Nouns do not decline according to number. jan can mean "person", "people", or "the human race" depending on context.

Toki Pona does not use isolated proper nouns; instead, they must modify a preceding noun. (For this reason they are called "proper adjectives"; they are functionally the same as compound nouns.)[12] For example, names of people and places are used as modifiers of the common roots for "person" and "place", e.g. ma Kanata (lit. "Canada country") or jan Lisa (lit. "Lisa person").

Modifiers

Phrases in Toki Pona are head-initial; modifiers always come after the word that they modify. This trait resembles the typical arrangement of adjectives in Spanish and Arabic and contrasts with the typical English structure. Thus a kasi kule, literally "plant of color", always means a kind of plant, the colorful kind (most likely a flower). A kasi kule poki, literally "plant of color of container" can only be the kind of "plant of color" that comes in a container, i.e. a potted flower.

In the other direction, the English expression "plant pot" refers to a kind of container, so it must be rendered into toki pona with the word meaning "container" at the beginning, i.e. poki kasi (literally "pot of plant"). A "flower pot" would be poki pi kasi kule (literally "pot of flower").

Order of operations differs from that in Lojban. In Toki Pona, "N A1 A2" (where N represents a noun and A1 and A2 represent modifiers) is always understood as ((N A1) A2), that is, an A1 N that is A2: E.g., jan pona lukin = ((jan pona) lukin), a friend watching (jan pona, "friend," literally "good person").

This can be changed with the particle pi, "of", which groups the following adjectives into a kind of compound adjective that applies to the head noun, which leads to jan pi pona lukin = (jan (pona lukin)), "good-looking person." Demonstratives, numerals, and possessive pronouns follow other modifiers.

Verbs

There is a zero copula.

Toki Pona does not inflect verbs according to person, tense, mood, or voice. Person is inferred from the subject of the verb; time is inferred from context or a temporal adverb in the sentence. The closest thing to passivity in Toki Pona is a structure such as "(result) of (subject) is because of (agent)." Alternatively, one could phrase a passive sentence as an active one with the agent subject being unknown.

Some prepositions can be used as a subclass of main verbs. For example, tawa means "to" as a preposition or "to go" or "to go to" as a verb; lon means "in" or "at" as a preposition or "exist, be in/at" as a verb; kepeken means "with" (in the sense of the instrumental case) as a preposition or "to use" as a verb. lon and tawa (but not kepeken) omit the direct object marker e before their objects: mi tawa tomo mi "I'm going to my house".

Vocabulary

The 120-root vocabulary is designed around the principles of living a simple life without the complications of modern civilization.[13] Because of the small number of roots in Toki Pona, words from other languages are often translated using a collocation of two or more roots, e.g. "to teach" by pana e sona, which literally means "to give knowledge".[6] Although Toki Pona is generally said to have only 115,[14] 118[15] or 120 "words", this is inaccurate, as there are many compound words and set phrases which, as idiomatic expressions, constitute independent lexical entries or lexemes and therefore must be memorized independently.

Colors

Toki Pona has five root words for colors: pimeja (black), walo (white), loje (red), jelo (yellow), and laso (blue). Each word represents multiple shades: laso refers to colors as light as cornflower blue or as dark as navy blue, even extending into shades of blue-green such as cyan.

Although the simplified conceptualization of colors tends to exclude a number of colors that are commonly expressed in Western languages, speakers sometimes may combine these five words to make more specific descriptions of certain colors. For instance, "purple" may be represented by combining laso and loje. The phrase laso loje means "a reddish shade of blue" and loje laso means "a bluish shade of red".

Numbers

Toki Pona has root words for one (wan), two (tu), and many (mute). In addition, ala can mean zero, although its more literal meaning is "no" or "none".[10]

Toki Ponans express larger numbers additively by using phrases such as tu wan for three, tu tu for four, and so on. This feature was added to make it impractical to communicate large numbers.[12]

An early description of the language uses luka (literally "hand") to signify "five". Although Lang has deprecated this feature in the latest official description of Toki Pona, its use is still common; from January to July 2006, it was used 10 times more often on the tokipona mailing list as a number than in its original sense of "hand". For example, using this structure luka luka luka wan would mean "sixteen".

Roots

Two words have archaic synonyms: nena replaced kapa (protuberance) early in the language's development for unknown reasons. Later, the pronoun ona replaced iki (he, she, it, they), which was sometimes confused with ike (bad).[12] Similarly, ali was added as an alternative to ale (all) to avoid confusion with ala (no, not) among people who reduce unstressed vowels, though both forms are still used.

Words that have been simply removed from the lexicon, without being replaced, include leko (block, stairs), kan (with), and pata (sibling, cousin).

Besides ali, nena, and ona, which replaced existing roots, two roots were added to the original 118: pan for cereals (grain, bread, pasta, rice, etc.) and esun for places of commerce (market, shop, etc.).

Provenance

Toki Pona roots generally come from English, Tok Pisin, Finnish, Georgian, Dutch, Acadian French, Esperanto, Croatian, and Chinese (Mandarin and Cantonese).

Many of these derivations are transparent. For example, oko (eye) is identical to Croatian oko and similar to other cognates such as Spanish ojo, Italian occhio and English ocular; likewise, toki (speech, language) is similar to Tok Pisin tok and its English source talk, while pona (good, positive), from Esperanto bona, reflects generic Romance bon, buona, etc. However, the changes in pronunciation required by the simple phonetic system make the origins of other words more difficult to see. The word lape (to sleep, to rest), for example, comes from Dutch slapen and is cognate with English sleep; kepeken (to use) is somewhat distorted from Dutch gebruiken, and akesi from hagedis (lizard) is scarcely recognizable. [Because *ti is not possible in Toki Pona, Dutch di comes through as si.]

Although only 14 roots (12%) are listed as derived from English, a large number of the Tok Pisin, Esperanto, and other roots are transparently cognate with English, raising the English-friendly portion of the vocabulary to about 30%. The portions of the lexicon from other languages are 15% Tok Pisin, 14% Finnish, 14% Esperanto, 12% Croatian, 10% Acadian, 9% Dutch, 8% Georgian, 5% Mandarin, 3% Cantonese; one root each from Welsh, Tongan (an English borrowing), Akan, and an uncertain language (apparently Swahili); four phonesthetic roots (two which are found in English, one from Japanese, and one which was made up); and one other made-up root (the grammatical particle e).

Literature

Lang has published proverbs, some poetry, and a basic phrase book in Toki Pona.[4]

Research

Toki Pona was chosen for the first version of the vocabulary for the ROILA project. The purpose of this project was to study the use of an artificial language on the accuracy of machine speech recognition.[16]

Community

During International Congress of Esperanto Youth held in Sarajevo, August 2006, there was a special session of Toki Pona speakers with 12 participants.

In 2007, Lang was reported to have said that at least 100 people speak Toki Pona fluently[1] and estimated that a few hundred have a basic knowledge of the language. Traffic on the Toki Pona mailing list and other online communities suggests that several hundred people have dabbled in it.

John Clifford, PhD, gave the following presentation on Toki Pona at the Second Language Creation Conference in 2007 at the University of California, Berkeley: "The Problems with Success: What Happens When an Opinionated Conlang Meets Its Speakers".[17][18]

Toki lili[19] is a microblogging site similar to Twitter specifically aimed at Toki Pona speakers.

There is an official Facebook group called toki pona created by Sonja Lang,[20] and there is an unofficial Facebook group called toki pona taso[21] which means "only toki pona." In the toki pona group, users communicate primarily in English about their interest in toki pona. In the toki pona taso group, users communicate solely in toki pona about various topics. As of November 2016, the toki pona group has over 2600 members, and the toki pona taso group has over 210 members.

Sample texts

mama pi mi mute (The Lord's Prayer)

Translation by Pije/Jopi

mama pi mi mute o, sina lon sewi kon.

nimi sina li sewi.

ma sina o kama.

jan o pali e wile sina lon sewi kon en lon ma.

o pana e moku pi tenpo suno ni tawa mi mute.

o weka e pali ike mi. sama la mi weka e pali ike pi jan ante.

o lawa ala e mi tawa ike.

o lawa e mi tan ike.

tenpo ali la sina jo e ma e wawa e pona.

Amen.

ma tomo Pape (The Tower of Babel story)

Translation by jan Siwen (Stephen Pope)

jan ali li kepeken e toki sama.

jan li kama tawa nasin pi kama suno li kama tawa ma Sinale li awen lon ni.

jan li toki e ni: "o kama! mi mute o pali e kiwen. o seli e ona."

jan mute li toki e ni: "o kama! mi mute o pali e tomo mute e tomo palisa suli. sewi pi tomo palisa li lon sewi kon. nimi pi mi mute o kama suli! mi wile ala e ni: mi mute li lon ma ante mute."

jan sewi Jawe li kama anpa li lukin e ma tomo e tomo palisa.

jan sewi Jawe li toki e ni: "jan li lon ma wan li kepeken e toki sama li pali e tomo palisa. tenpo ni la ona li ken pali e ijo ike mute. mi wile tawa anpa li wile pakala e toki pi jan mute ni. mi wile e ni: jan li sona ala e toki pi jan ante."

jan sewi Jawe li kama e ni: jan li lon ma mute li ken ala pali e tomo.

nimi pi ma tomo ni li Pape tan ni: jan sewi Jawe li pakala e toki pi jan ali. jan sewi Jawe li tawa e jan tawa ma mute tan ma tomo Pape.

wan taso (Alone)

dark teenage poetry

ijo li moku e mi. (Something is eating me.)

mi wile pakala. (I want to hurt.)

pimeja li tawa insa kon mi. (Darkness goes inside of me.)

jan ala li ken sona e pilin ike mi. (Nobody can know my pain.)

toki musi o, sina jan pona mi wan taso. (Poetry, you are my one and only friend.)

telo pimeja ni li telo loje mi, li ale mi. (This ink is my blood, is my all.)

tenpo ale la pimeja li lon. (Darkness always exists.)

See also

- Alphabet of human thought

- Hyponymy

- Natural semantic metalanguage

- Philosophical language

- Pirahã language

References

- 1 2 Roberts, Siobhan (9 July 2007). "Canadian has people talking about lingo she created". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- ↑ "Canadian has people talking about lingo she created". Retrieved 2013-12-11.

- ↑ "Step aside, Tolkien fans and grunting Klingonists: Newly invented tongues are creeping into the public domain, thanks to the Web." (PDF). Retrieved 2013-12-11.

- 1 2 3 "the simple language of good". Toki Pona. 2009-10-10. Retrieved 2009-12-19.

- ↑ A Million Words and Counting: How Global English Is Rewriting the World, Paul J. J. Payack, (C) 2007, p. 194.

- 1 2 Станислав Козловский (Stanislav Kozlovsky) (20 July 2004). "Скорость мысли (The Speed of Thought)" (in Russian). Компьютерра Online (Computerra Online). Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- ↑ Roberts, Siobhan (July 9, 2007). "Canadian has people talking about lingo she created". The Globe and Mail.

- ↑ "Toki Pona: kalama / sounds". Archive.is. 2006-05-27.

- ↑ "Phoneme frequency table" in lipu pi toki pona pi jan Jakopo

- 1 2 Toki Pona: nimi ale / word list

- ↑ Dance, Amber (August 24, 2007). "In their own words – literally". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2007-08-29. – paid version and PDF version

- 1 2 3 Yerrick, Damian (October 23, 2002). "Toki Pona li pona ala pona? A review of the Toki Pona planned language". Pin Eight. Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- ↑ Originally 118 roots, with two roots added later.

- ↑ Hrafn Loftsson, Eirikur Rögnvaldsson, Sigrun Helgadottir Advances in Natural Language Processing: 7th International 2010 - Page 251 "As a starting point for the first version of the vocabulary of ROILA we choose the artificial language Toki Pona [6] which caters for the expression of very simple concepts by just 115 words. Therefore this number formed the size of the ROILA"

- ↑ Tom Gross, Jan Gulliksen, Paula Kotzé Human-Computer Interaction - INTERACT 2009: 12th IFIP TC 13 2009 Page 850 "As a first step in the design process we aim to inherit the vocabulary set or word concepts of the simple artificial language Toki Pona [12]. It has 118 word concepts and sufficiently caters for the needs of a simple language. We aim to adapt the ..."

- ↑ Omar Mubin; Christoph Bartneck; Loe Feijs (2010-08-19). "Towards the Design and Evaluation of ROILA". Bartneck.de. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-14770-8_28. Retrieved 2013-12-11.

- ↑ "Second Language Creation Conference 2007". Dedalvs.conlang.org. Retrieved 2013-12-11.

- ↑ "Second Language Creation Conference Handouts" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-12-11.

- ↑ toki lili. "tokilili.shoutem.com". tokilili.shoutem.com. Retrieved 2013-12-11.

- ↑ "toki pona". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 2016-05-04.

- ↑ "toki pona taso". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 2016-05-04.

- Тијана Јовановић (Tijana Jovanović); Политикин Забавник (Politikin Zabavnik) (15 December 2006). "Вештачки језици-Токи пона (Constructed language-Toki Pona)" (in Serbian) (2862). Забавник. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help)

- Marek Blahuš (2011). "Toki pona – eine minimalistische Plansprache (Toki Pona – a minimalist constructed language)". Spracherfindung und ihre Ziele. Beiträge der 20. Jahrestagung der Gesellschaft für Interlinguistik e.V., 26.-28. November 2010 in Berlin. (in German). Sabine Fiedler (18).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Toki pona. |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Toki Pona |

- Official website

- Fail Blue Dot translations of some classic literature as well as some original works.

- tomo-lipu.net Texts written in sitelen-pona. Each toki-pona word is represented by a unique logogram or symbol

- lipu pi jan Jakopo with pangrams, phoneme frequency analysis, lessons in Esperanto, and links to isolate sites.

- Bivax Productions produced three short films in Toki Pona.