Finnish language

| Finnish | |

|---|---|

| suomen kieli | |

| Pronunciation | IPA: [ˈsuomi] |

| Native to | Finland, Sweden, Norway (Only very small parts in Troms and Finnmark), Russia |

Native speakers | 5.4 million (2009–2012)[1] |

|

Latin (Finnish alphabet) Finnish Braille | |

| Signed Finnish | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

1 Country 1 Organisation |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Language Planning Department of the Institute for the Languages of Finland |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 |

fi |

| ISO 639-2 |

fin |

| ISO 639-3 |

fin |

| Glottolog |

finn1318[4] |

| Linguasphere |

41-AAA-a |

|

Official language.

Spoken by a minority. | |

Finnish (![]() suomi , or suomen kieli [ˈsuomen ˈkieli]) is the language spoken by the majority of the population in Finland and by ethnic Finns outside Finland. It is one of the two official languages of Finland and an official minority language in Sweden. In Sweden, both standard Finnish and Meänkieli, a Finnish dialect, are spoken. The Kven language, a dialect of Finnish, is spoken in Northern Norway by a minority group of Finnish descent.

suomi , or suomen kieli [ˈsuomen ˈkieli]) is the language spoken by the majority of the population in Finland and by ethnic Finns outside Finland. It is one of the two official languages of Finland and an official minority language in Sweden. In Sweden, both standard Finnish and Meänkieli, a Finnish dialect, are spoken. The Kven language, a dialect of Finnish, is spoken in Northern Norway by a minority group of Finnish descent.

Finnish is the eponymous member of the Finnic language family and is typologically between fusional and agglutinative languages. It modifies and inflects nouns, adjectives, pronouns, numerals and verbs, depending on their roles in the sentence.

Classification

Finnish is a member of the Finnic group of the Uralic family of languages. The Finnic group also includes Estonian and a few minority languages spoken around the Baltic Sea.

Finnish demonstrates an affiliation with other Uralic languages (such as Hungarian/Magyar) in several respects including:

- Shared morphology:

- case suffixes such as genitive -n, partitive -(t)a / -(t)ä ( < Uralic *-ta, originally ablative), essive -na / -nä ( < *-na, originally locative)

- plural markers -t and -i- ( < Uralic *-t and *-j, respectively)

- possessive suffixes such as 1st person singular -ni ( < Uralic *-n-mi), 2nd person singular -si ( < Uralic *-ti).

- various derivational suffixes (e.g. causative -tta/-ttä < Uralic *-k-ta)

- Shared basic vocabulary displaying regular sound correspondences with the other Uralic languages (e.g. kala 'fish' ~ North Saami guolli ~ Hungarian hal; and kadota 'disappear' ~ North Saami guođđit ~ Hungarian hagy 'leave (behind)'.

Several theories exist as to the geographic origin of Finnish and the other Uralic languages. The most widely held view is that they originated as a Proto-Uralic language somewhere in the boreal forest belt around the Ural Mountains region and/or the bend of the middle Volga. The strong case for Proto-Uralic is supported by common vocabulary with regularities in sound correspondences, as well as by the fact that the Uralic languages have many similarities in structure and grammar.

The Finns are more genetically similar to their Indo-European-speaking neighbours than to the speakers of the geographically close Uralic language Sami. It has been argued that a native Finnic-speaking population absorbed northward migrating Indo-European speakers who adopted the Finnic language, giving rise to the modern Finns.[5]

The Defense Language Institute in Monterey, California, United States classifies Finnish as a level III language (of 4 levels) in terms of learning difficulty for native English speakers.[6]

Geographic distribution

Finnish is spoken by about five million people, most of whom reside in Finland. There are also notable Finnish-speaking minorities in Sweden, Norway, Russia, Estonia, Brazil, Canada, and the United States. The majority of the population of Finland, 90.37% as of 2010, speak Finnish as their first language.[7] The remainder speak Swedish (5.42%),[7] Sami (Northern, Inari, Skolt) and other languages. It has achieved some popularity as a second language in Estonia.

Official status

Finnish is one of two official languages of Finland (the other being Swedish, spoken by 5.42% of the population as of 2010[7]) and one of the official languages in the European Union since 1995. Finnish language started to gain its role during the Grand Duchy of Finland, along with the nationalistic Fennoman movement, and obtained its official status in the Finnish Diet of 1863. It enjoys the status of an official minority language in Sweden. Under the Nordic Language Convention, citizens of the Nordic countries speaking Finnish have the opportunity to use their native language when interacting with official bodies in other Nordic countries without being liable to any interpretation or translation costs.[8][9]

History

Prehistory

The Finnic languages evolved from the Proto-Finnic language after Sámi was separated from it around 1500–1000 BCE. Current models assume three or more hypothetical Proto-Finnic proto-dialects evolving over the first millennium BCE.[10]

Medieval period

Prior to the Middle Ages, Finnish was solely an oral language. Even after, the language of larger-scale business was Middle Low German, the language of administration Swedish, and religious activities were held in Latin, leaving few possibilities for Finnish-speakers to use their mother tongue in situations other than daily chores.

The first known written example of Finnish comes from this era and was found in a German travel journal dating back to c.1450: Mÿnna tachton gernast spuho somen gelen emÿna daÿda (Modern Finnish: "Minä tahdon kernaasti puhua suomen kieltä, [mutta] en minä taida;" English: "I want to speak Finnish, [but] I am not able").[11] According to the travel journal, a Finnish bishop, whose name is unknown, was behind the above quotation. The contextually erroneous accusative case in gelen (Finnish kielen) and the lack of the conjunction mutta seem to indicate a foreign speaker with an incomplete grasp of Finnish grammar, as errors with the numerous noun cases are typical of those learning Finnish.[12] Finnish priestdom at the time was largely Swedish-speaking.[13]

Writing system

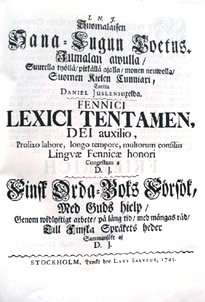

The first comprehensive writing system for Finnish was created by Mikael Agricola, a Finnish bishop, in the 16th century. He based his orthography on Swedish, German, and Latin. His ultimate plan was to translate the Bible, but first he had to define rules on which the Finnish standard language still relies, particularly with respect to spelling.

Agricola's written language was based on western dialects of Finnish, and his intention was that each phoneme should correspond to one letter. Yet, Agricola was confronted with many problems in this endeavour and failed to achieve uniformity. This is why he might use different signs for the same phonemes depending on the situation. For example, he used dh or d to represent the voiced dental fricative /ð/ (English th in this) and tz or z to represent the geminate unvoiced dental fricative /θ/ (the th in thin). Additionally, Agricola might use gh or g to represent the voiced velar fricative /ɣ/ and either ch, c or h for /h/. For example, he wrote techtin against modern spelling tehtiin.

Others revised Agricola's work later, striving for a more phonemic system. Along the way, Finnish lost some of its phonemes. The sounds /ð/ and /θ/ disappeared from the standard language, surviving only in a small rural region in Western Finland.[14] Elsewhere, traces of these phonemes persist as their disappearance gave Finnish dialects their distinct qualities. For example, /θ/ became ht or tt (e.g. meþþä → mehtä, mettä) in the eastern dialects and in some western dialects. In the standard language, however, the effect of the lost phonemes is thus:

- /ð/ became /d/

- /θ/ became /ts/

- /ɣ/ became /v/ but only if the /ɣ/ appeared originally between high labial vowels /u/ and /y/, otherwise lost entirely (cf. suku 'kin, family' : suvun [genitive form] from earlier *suku : *suɣun, and kyky : kyvyn 'ability, skill' [nominative and genitive, respectively] from *kükü : *küɣün, contrasting with sika : sian 'pig, pork' [nominative and genitive] from *sika : *siɣan).

Modern Finnish punctuation, along with that of Swedish, uses the colon character to separate the stem of the word and its grammatical ending in some cases (such as after abbreviations), where some other alphabetic writing systems would use an apostrophe. Suffixes are required for correct grammar, so this is often applied, e.g. EU:ssa "in the EU".

Modernization

In the 19th century Johan Vilhelm Snellman and others began to stress the need to improve the status of Finnish. Ever since the days of Mikael Agricola, written Finnish had been used almost exclusively in religious contexts, but now Snellman's Hegelian nationalistic ideas of Finnish as a fully-fledged national language gained considerable support. Concerted efforts were made to improve the status of the language and to modernize it, and by the end of the century Finnish had become a language of administration, journalism, literature, and science in Finland, along with Swedish.

The most important contributions to improving the status of Finnish were made by Elias Lönnrot. His impact on the development of modern vocabulary in Finnish was particularly important. In addition to compiling the Kalevala, he acted as an arbiter in disputes about the development of standard Finnish between the proponents of western and eastern dialects, ensuring that the western dialects Agricola had preferred preserved their preeminent role, while many originally dialect words from Eastern Finland were introduced to the standard language, enriching it considerably.[15] The first novel written in Finnish (and by a Finnish-speaker) was Seven Brothers (Seitsemän veljestä), published by Aleksis Kivi in 1870.

Dialects

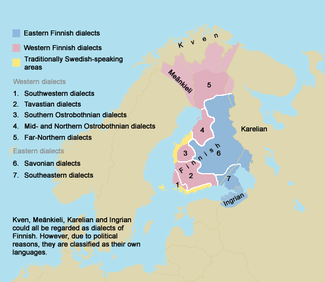

The dialects of Finnish are divided into two distinct groups, Western and Easterns.[16] The dialects are almost entirely mutually intelligible and are distinguished from each other by only minor changes in vowels, diphthongs and rhythm. For the most part, the dialects operate on the same phonology, grammar and vocabulary. There are only marginal examples of sounds or grammatical constructions specific to some dialect and not found in standard Finnish. Two examples are the voiced dental fricative found in the Rauma dialect, and the Eastern exessive case.

The classification of closely related dialects spoken outside Finland is a politically sensitive issue that has been controversial since Finland's independence in 1917. This concerns specifically the Karelian language in Russia and Meänkieli in Sweden, the speakers of which are often considered oppressed minorities. Karelian is different enough from standard Finnish to have its own orthography. Meänkieli is a northern dialect entirely intelligible to speakers of any other Finnish dialect, which achieved its status as an official minority language in Sweden for historical and political reasons, although Finnish is an official minority language in Sweden, too.

Western dialects

The South-West dialects (lounaismurteet) are spoken in Southwest Finland and Satakunta. Their typical feature is abbreviation of word-final vowels, and in many respects they resemble Estonian. The Tavastian dialects (hämäläismurteet) are spoken in Tavastia. They are closest to the standard language, but feature some slight vowel changes, such as the opening of diphthong-final vowels (tie → tiä, miekka → miakka, kuolisi → kualis). The Southern Ostrobothnian dialects (eteläpohjalaiset murteet) are spoken in Southern Ostrobothnia. Their most notable feature is the pronunciation of 'd' as a tapped or even fully trilled /r/. The Middle and North Ostrobothnia dialects (keski- ja pohjoispohjalaiset murteet) are spoken in Central and Northern Ostrobothnia. The Far Northern dialects (peräpohjalaiset murteet) are spoken in Lapland. The dialects spoken in the western parts of Lapland are recognizable by retention of old 'h' sounds in positions where they have disappeared from other dialects.

One of the Far Northern dialects, Meänkieli, which is spoken on the Swedish side of the border, is taught in some Swedish schools as a distinct standardized language. The speakers of Meänkieli became politically separated from the other Finns when Finland was annexed to Russia in 1809. The categorization of Meänkieli as a separate language is controversial among the Finns, who see no linguistic criteria, only political reasons, for treating Meänkieli differently from other dialects of Finnish.

The Kven language is spoken in Finnmark and Troms, in Norway. Its speakers are descendants of Finnish emigrants to the region in the 18th and 19th centuries. Kven is an official minority language in Norway.

Eastern dialects

The Eastern dialects consist of the widespread Savonian dialects (savolaismurteet) spoken in Savo and nearby areas, and the South-Eastern dialects now spoken only in Finnish South Karelia. The South-Eastern dialects (kaakkoismurteet) were previously also spoken on the Karelian Isthmus and in Ingria. The Karelian Isthmus was evacuated during World War II and refugees were resettled all over Finland. Most Ingrian Finns were deported to various interior areas of the Soviet Union.

Palatalization, a common feature of Uralic languages, had been lost in the Finnic branch, but it has been reacquired by most of these languages, including Eastern Finnish, but not Western Finnish. In Finnish orthography, this is denoted with a 'j', e.g. vesj [vesʲ] 'water', cf. standard vesi.

The language spoken in those parts of Karelia that have not historically been under Swedish or Finnish rule is usually called the Karelian language, and it is considered to be more distant from standard Finnish than the Eastern dialects. Whether this language of Russian Karelia is a dialect of Finnish or a separate language is a matter of interpretation. However, the term "Karelian dialects" is often used colloquially for the Finnish South-Eastern dialects.

Dialect chart of Finnish

- Western dialects

- Southern-Western dialects

- Proper Southern-Western dialects

- Northern dialect group

- Southern dialect group

- Southern-Western middle dialects

- Pori region dialects

- Ala-Satakunta dialects

- dialects of Turku highlands

- Somero region dialects

- Western Uusimaa dialects

- Proper Southern-Western dialects

- Tavastian dialects

- Ylä-Satakunta dialects

- Heart Tavastian dialects

- Southern Tavastian dialects

- Southern-Eastern Tavastian dialects

- Hollola dialect group

- Porvoo dialect group

- Iitti dialect group

- Southern Botnian dialects

- Middle and Northern Botnian dialects

- Middle Botnian dialects

- Northern Botnian dialects

- Peräpohjola dialects

- Tornio dialects ("Meänkieli" in Sweden)

- Kemi dialects

- Kemijärvi dialects

- Jällivaara dialects ("Meänkieli" in Sweden)

- Ruija dialects ("Kven language" in Northern Norway)

- Southern-Western dialects

- Eastern dialects

- Savonian dialects

- Northern Savonian dialects

- Southern Savonian dialects

- Middle dialects of Savonlinna region

- Eastern Savonian dialects or the dialects of North Karelia

- Kainuu dialects

- Central Finland dialects

- Päijänne Tavastia dialects

- Keuruu-Evijärvi dialects

- Savonian dialects of Värmland (Sweden)

- Southern-Eastern dialects

- Proper Southern-Eastern dialects

- Middle dialects of Lemi region

- Dialects of Ingria (in Russia)[17]

- Savonian dialects

Linguistic varieties

There are two main varieties of Finnish used throughout the country. One is the "standard language" (yleiskieli), and the other is the "spoken language" (puhekieli). The standard language is used in formal situations like political speeches and newscasts. Its written form, the "book language" (kirjakieli), is used in nearly all written texts, not always excluding even the dialogue of common people in popular prose. The spoken language, on the other hand, is the main variety of Finnish used in popular TV and radio shows and at workplaces, and may be preferred to a dialect in personal communication.

Standardization

Standard Finnish is prescribed by the Language Office of the Research Institute for the Languages of Finland and is the language used in official communication. The Dictionary of Contemporary Finnish (Nykysuomen sanakirja 1951–61), with 201,000 entries, was a prescriptive dictionary that defined official language. An additional volume for words of foreign origin (Nykysuomen sivistyssanakirja, 30,000 entries) was published in 1991. An updated dictionary, The New Dictionary of Modern Finnish (Kielitoimiston sanakirja) was published in an electronic form in 2004 and in print in 2006. A descriptive grammar (Iso suomen kielioppi,[18] 1,600 pages) was published in 2004. There is also an etymological dictionary, Suomen sanojen alkuperä, published in 1992–2000, and a handbook of contemporary language (Nykysuomen käsikirja), and a periodic publication, Kielikello. Standard Finnish is used in official texts and is the form of language taught in schools. Its spoken form is used in political speech, newscasts, in courts, and in other formal situations. Nearly all publishing and printed works are in standard Finnish.

Colloquial Finnish

The colloquial language has mostly developed naturally from earlier forms of Finnish, and spread from the main cultural and political centres. The standard language, however, has always been a consciously constructed medium for literature. It preserves grammatical patterns that have mostly vanished from the colloquial varieties and, as its main application is writing, it features complex syntactic patterns that are not easy to handle when used in speech. The colloquial language develops significantly faster, and the grammatical and phonological simplifications also include the most common pronouns and suffixes, which sum up to frequent but modest differences. Some sound changes have been left out of the formal language, such as the irregularization of some common verbs by assimilation, e.g. tule- → tuu- ('come', only when the second syllable is short, so the third person singular does not contract: hän tulee 'he comes', never *hän tuu; also mene- → mee-). However, the longer forms such as tule can be used in spoken language in other forms as well.

The literary language certainly still exerts a considerable influence upon the spoken word, because illiteracy is nonexistent and many Finns are avid readers. In fact, it is still not entirely uncommon to meet people who "talk book-ish" (puhuvat kirjakieltä); it may have connotations of pedantry, exaggeration, moderation, weaseling or sarcasm (somewhat like heavy use of Latinate words in English: compare the difference between saying "There's no children I will leave it to" and "There are no children to whom I shall leave it".). More common is the intrusion of typically literary constructions into a colloquial discourse, as a kind of quote from written Finnish. It should also be noted that it is quite common to hear book-like and polished speech on radio or TV, and the constant exposure to such language tends to lead to the adoption of such constructions even in everyday language.

A prominent example of the effect of the standard language is the development of the consonant gradation form /ts : ts/ as in metsä : metsän, as this pattern was originally (1940) found natively only in the dialects of southern Karelian isthmus and Ingria. It has been reinforced by the spelling 'ts' for the dental fricative [θː], used earlier in some western dialects. The spelling and the pronunciation encouraged by it however approximate the original pronunciation, still reflected e.g. in Karelian /čč : č/ (meččä : mečän). In spoken language, a fusion of Western /tt : tt/ (mettä : mettän) and Eastern /ht : t/ (mehtä : metän) has been created: /tt : t/ (mettä : metän).[19] It is notable that neither of these forms are identifiable as, or originate from, a specific dialect.

The orthography of the informal language follows that of the formal language. However, sometimes sandhi may be transcribed, especially the internal ones, e.g. menenpä → menempä. This never takes place in formal language.

Examples

formal language colloquial language meaning he menevät ne menee "they go" (loss of distinction of animacy and the difference between the plural and the singular) onko teillä o(n)ks teil(lä) "do you (pl.) have?" (apocope) (me) emme sano m'ei sanota "we don't say" or "we won't say" (the first person plural is replaced with the passive voice) (minun) kirjani mun kirja "my book" (possessive suffix not used) kuusikymmentäviisi kuuskyt(ä)viis "sixty-five" (abbreviated forms of numbers) minä tulen mä tuun "I'm coming" or "I will come" (irregular verb, no pro-dropping) punainen punane(n) or punaine "red" (unstressed diphthong becomes a short vowel) korjannee kai korjaa "probably will fix" (absence of the potential mood) hyvää huomenta huomenta good morning

Note that there are noticeable differences between dialects. Also note that here the formal language does not mean a language spoken in formal occasions but the standard language which exists practically only in written form.

Phonology

Characteristic features of Finnish (common to some other Uralic languages) are vowel harmony and an agglutinative morphology; owing to the extensive use of the latter, words can be quite long.

The main stress is always on the first syllable, and it is articulated by adding approximately 100 ms more length to the stressed vowel.[20] Stress does not cause any measurable modifications in vowel quality (very much unlike English). However, stress is not strong and words appear evenly stressed. In some cases, stress is so weak that the highest points of volume, pitch and other indicators of "articulation intensity" are not on the first syllable, although native speakers recognize the first syllable as a stressed syllable.

There are eight vowels, whose lexical and grammatical role is highly important, and which are unusually strictly controlled, so that there is almost no allophony. Vowels are shown in the table below, followed by the IPA symbol. These are always different phonemes in the initial syllable; for noninitial syllable, see morphophonology below. There is no close-mid/open-mid distinction, with true mid or open-mid being used in all cases.

| Front | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unrounded | Rounded | Unrounded | Rounded | |

| Close | i [i] | y [y] | u [u] | |

| Mid | e [e] | ö [ø] | o [o] | |

| Open | ä [æ] | a [ɑ] | ||

The usual analysis is that Finnish has long and short vowels and consonants as distinct phonemes. However, long vowels may be analyzed as a vowel followed by a chroneme, or also, that sequences of identical vowels are pronounced as "diphthongs". The quality of long vowels mostly overlaps with the quality of short vowels, with the exception of u, which is centralized with respect to uu; long vowels do not morph into diphthongs. There are eighteen phonemic diphthongs; like vowels, diphthongs do not have significant allophony.

Finnish has a consonant inventory of small to moderate size, where voicing is mostly not distinctive, and fricatives are scarce. Finnish has relatively few non-coronal consonants. Consonants are as follows, where consonants in parenthesis are found only in a few recent loans, and may be mispronounced by uneducated speakers.

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Postalveolar/ Palatal |

Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ [note 1] | |||

| Plosive | p, (b) | t, d [note 2] | k, (ɡ) | ʔ [note 3] | ||

| Fricative | (f) | s | (ʃ) | h | ||

| Approximant | ʋ | l | j | |||

| Trill | r |

- ↑ The short velar nasal is an allophone of /n/ in /nk/, and the long velar nasal /ŋŋ/, written ng, is the equivalent of /nk/ under weakening consonant gradation (type of lenition) and thus occurs only medially, e.g. Helsinki – Helsingin kaupunki (city of Helsinki) /hɛlsiŋki – hɛlsiŋŋin/.

- ↑ /d/ is the equivalent of /t/ under weakening consonant gradation, and thus occurs only medially, or in non-native words; it is actually more of an alveolar tap rather than a true voiced stop, and the dialectal realization varies widely; see the main article on Finnish phonology.

- ↑ The glottal stop can only appear at word boundaries as a result of certain sandhi phenomena, and it is not indicated in spelling: e.g. /annaʔolla/ 'let it be', orthographically anna olla. Moreover, this sound is not used in all dialects.

Almost all consonants have phonemic geminated forms. These are independent, but occur only medially when phonemic.

Independent consonant clusters are not allowed in native words, except for a small set of two-consonant syllable codas, e.g. 'rs' in karsta. However, because of a number of recently adopted loanwords using them, e.g. strutsi from Swedish struts, meaning "ostrich", Finnish speakers can pronounce them, even if it is somewhat awkward.

As a Uralic language, it is somewhat special in two respects: loss of fricatives and loss of palatalization. Finnish has only two fricatives in native words, namely /s/ and /h/. All other fricatives are recognized as foreign, of which Finnish speakers can usually reliably distinguish /f/ and /ʃ/. (The official alphabet includes 'z' [z] and 'ž' [ʒ], but these are rarely used correctly, including by the Swedish-speakers, who also struggle with those sounds.) Palatalization is characteristic of Uralic languages, but Finnish has lost it. However, the Eastern dialects and the Karelian language have redeveloped a system of palatalization. For example, the Karelian word d'uuri [dʲuːri], with a palatalized /dʲ/, is reflected by juuri in Finnish and Savo dialect vesj [vesʲ] is vesi in standard Finnish.

A feature of Finnic phonology is the development of labial and rounded vowels in non-initial syllables, as in the word tyttö. Proto-Uralic had only 'a' and 'i' and their vowel harmonic allophones in non-initial syllables; modern Finnish allows other vowels in non-initial syllables, although they are uncommon compared to 'a', 'ä' and 'i'.

Morphophonology

Finnish has several morphophonological processes that require modification of the forms of words for daily speech. The most important processes are vowel harmony and consonant gradation.

Vowel harmony is a redundancy feature, which means that the feature [±back] is uniform within a word, and so it is necessary to interpret it only once for a given word. It is meaning-distinguishing in the initial syllable, and suffixes follow; so, if the listener hears [±back] in any part of the word, they can derive [±back] for the initial syllable. For example, from the stem tuote ("product") one derives tuotteeseensa ("into his product"), where the final vowel becomes the back vowel 'a' (rather than the front vowel 'ä') because the initial syllable contains the back vowels 'uo'. This is especially notable because vowels 'a' and 'ä' are different, meaning-distinguishing phonemes, not interchangeable or allophonic. Finnish front vowels are not umlauts.

Consonant gradation is a lenition process for P, T and K, with the oblique stem "weakened" from the nominative stem, or vice versa. For example, tarkka "precise" has the oblique root tarka-, as in tarkan "of the precise". There is also another gradation pattern, which is older, and causes simple elision of T and K. However, it is very common since it is found in the partitive case marker: if V is a single vowel, V+ta → Va, e.g. *vanha+ta → vanhaa. Another instance is the imperative, which changes into a glottal stop in the singular but is shown as an overt 'ka' in plural, e.g. mene vs. menkää.

Grammar

Finnish is a synthetic language that employs extensive regular agglutination of modifiers to verbs, nouns, adjectives and numerals. However, Finnish is not a polysynthetic language, although non-finite dependent clauses may be contracted to infinitives (lauseenvastike, e.g. juode·ssa·ni "when I was drinking", lit. "drink-in-I").

The morphosyntactic alignment is nominative–accusative; but there are two object cases: accusative and partitive. The contrast between the two is telic, where the accusative case denotes actions completed as intended (Ammuin hirven "I shot (killed) the elk"), and the partitive case denotes incomplete actions (Ammuin hirveä "I shot (at) the elk"). Often this is confused with perfectivity, but the only element of perfectivity that exists in Finnish is that there are some perfective verbs. Transitivity is distinguished by different verbs for transitive and intransitive, e.g. ratkaista "to solve something" vs. ratketa "to solve by itself". There are several frequentative and momentane verb categories.

Verbs gain personal suffixes for each person; these suffixes are grammatically more important than pronouns, which are often not used at all in standard Finnish. The infinitive is not the uninflected form but has a suffix -ta or -da; the closest one to an uninflected form is the third person singular indicative. There are four persons, first ("I, we"), second ("you (singular), you (plural)"), third ("s/he, they"). The passive voice (sometimes called impersonal or indefinite) resembles a "fourth person" similar to, e.g., English "people say/do/...". There are four tenses, namely present, past, perfect and pluperfect; the system mirrors the Germanic system. The future tense is not needed, because of context and the telic contrast. For example, luen kirjan "I read a book (completely)" indicates a future, when luen kirjaa "I read a book (not yet complete)" indicates present.

Nouns may be suffixed with the markers for the aforementioned accusative case and partitive case, the genitive case, eight different locatives, and a few other cases. The case marker must be added not only to the main noun, but also to its modifiers; e.g. suure+ssa talo+ssa, literally "big-in house-in". Possession is marked with a possessive suffix; separate possessive pronouns are unknown. Pronouns gain suffixes just as nouns do.

Lexicon

- See the lists of Finnish words and words of Finnish origin at Wiktionary, the free dictionary and Wikipedia's sibling project.

Finnish has a smaller core vocabulary than, for example, English, and uses derivative suffixes to a greater extent. As an example, take the word kirja "a book", from which one can form derivatives kirjain "a letter" (of the alphabet), kirje "a piece of correspondence, a letter", kirjasto "a library", kirjailija "an author", kirjallisuus "literature", kirjoittaa "to write", kirjoittaja "a writer", kirjuri "a scribe, a clerk", kirjallinen "in written form", kirjata "to write down, register, record", kirjasin "a font", and many others.

Here are some of the more common such suffixes. Which of each pair is used depends on the word being suffixed in accordance with the rules of vowel harmony.

- -ja/jä : agent (one who does) (e.g. lukea "to read" → lukija "reader")

- -lainen/läinen: inhabitant of (either noun or adjective). Englanti "England" → englantilainen "English person or thing"; Venäjä → venäläinen "Russian person or thing".

- -sto/stö: collection of. For example: kirja "a book" → kirjasto "a library"; laiva "a ship" → laivasto "navy, fleet".

- -in: instrument or tool. For example: kirjata "to book, to file" → kirjain "a letter" (of the alphabet); vatkata "to whisk" → vatkain "a whisk, mixer".

- -uri/yri: an agent or instrument (kaivaa "to dig" → kaivuri "an excavator"; laiva "a ship" → laivuri "shipper, shipmaster").

- -os/ös: result of some action (tulla "to come" → tulos "result, outcome"; tehdä "to do" → teos "a piece of work").

- -ton/tön: lack of something, "un-", "-less" (onni "happiness" → onneton "unhappy"; koti "home" → koditon "homeless").

- -llinen: having (the quality of) something (lapsi "a child" → lapsellinen "childish"; kauppa "a shop, commerce" → kaupallinen "commercial").

- -kas/käs: similar to -llinen (itse "self" → itsekäs "selfish"; neuvo "advice" → neuvokas "resourceful").

- -va/vä: doing or having something (taitaa "to be able" → taitava "skillful"; johtaa "to lead" → johtava "leading").

- -la/lä: a place related to the main word (kana "a hen" → kanala "a henhouse"; pappi "a priest" → pappila "a parsonage").

Verbal derivational suffixes are extremely diverse; several frequentatives and momentanes differentiating causative, volitional-unpredictable and anticausative are found, often combined with each other, often denoting indirection. For example, hypätä "to jump", hyppiä "to be jumping", hypeksiä "to be jumping wantonly", hypäyttää "to make someone jump once", hyppyyttää "to make someone jump repeatedly" (or "to boss someone around"), hyppyytyttää "to make someone to cause a third person to jump repeatedly", hyppyytellä "to, without aim, make someone jump repeatedly", hypähtää "to jump suddenly" (in anticausative meaning), hypellä "to jump around repeatedly", hypiskellä "to be jumping repeatedly and wantonly". Caritives are also used in such examples as hyppimättä "without jumping" and hyppelemättä "without jumping around". The diversity and compactness of both derivation and inflectional agglutination can be illustrated with istahtaisinkohan "I wonder if I should sit down for a while" (from istua, "to sit, to be seated"):

- istua "to sit down" (istun "I sit down")

- istahtaa "to sit down for a while"

- istahdan "I'll sit down for a while"

- istahtaisin "I would sit down for a while"

- istahtaisinko "should I sit down for a while?"

- istahtaisinkohan "I wonder if I should sit down for a while"

Borrowing

Over the course of many centuries, the Finnish language has borrowed many words from a wide variety of languages, most from neighbouring Indo-European languages. Indeed, some estimates put the core Proto-Uralic vocabulary surviving in Finnish at only around 300 word roots. Owing to the different grammatical, phonological and phonotactic structure of the Finnish language, loanwords from Indo-European have been assimilated.

In general, the first loan words into Uralic languages seem to come from very early Indo-European languages, and later mainly from Iranian, Turkic, Baltic, Germanic, and Slavic languages. Furthermore, a certain group of very basic and neutral words exists in Finnish and other Finnic languages that are absent from other Uralic languages, but without a recognizable etymology from any known language. These words are usually regarded as the last remnant of the Paleo-European language spoken in Fennoscandia before the arrival of the proto-Finnic language. Words included in this group are e.g. jänis (hare), musta (black), mäki (hill), saari (island), suo (swamp) and niemi (cape (geography)).

Also some place names, like Päijänne and Imatra, are probably before the proto-Finnic era.[21]

Often quoted loan examples are kuningas "king" and ruhtinas "sovereign prince, high ranking nobleman" from Germanic *kuningaz and *druhtinaz—they display a remarkable tendency towards phonological conservation within the language. Another example is äiti "mother", from Gothic aiþei, which is interesting because borrowing of close-kinship vocabulary is a rare phenomenon. The original Finnish emo occurs only in restricted contexts. There are other close-kinship words that are loaned from Baltic and Germanic languages (morsian "bride", armas "dear", huora "whore"). Examples of the ancient Iranian loans are vasara "hammer" from Avestan vadžra, vajra and orja "slave" from arya, airya "man" (the latter probably via similar circumstances as slave from Slav in many European languages).

More recently, Swedish has been a prolific source of borrowings, and also, the Swedish language acted as a proxy for European words, especially those relating to government. Present-day Finland was a part of Sweden from the 12th century and was ceded to Russia in 1809, becoming an autonomous Grand Duchy. Swedish was retained as the official language and language of the upper class even after this. When Finnish was accepted as an official language, it gained only legal "equal status" with Swedish, which persists even today. It is still the case today, though only about 5.5% of Finnish nationals, the Swedish-speaking Finns, have Swedish as their mother tongue. During the period of autonomy, Russian did not gain much ground as a language of the people or the government. Nevertheless, quite a few words were subsequently acquired from Russian (especially in older Helsinki slang) but not to the same extent as with Swedish. In all these cases, borrowing has been partly a result of geographical proximity.

Especially words dealing with administrative or modern culture came to Finnish from Swedish, sometimes reflecting the oldest Swedish form of the word (lag – laki, 'law'; län – lääni, 'province'; bisp – piispa, 'bishop'; jordpäron – peruna, 'potato'), and many more survive as informal synonyms in spoken or dialectal Finnish (e.g. likka, from Swedish flicka, 'girl', usually tyttö in Finnish).

Typical Russian loanwords are old or very old, thus hard to recognize as such, and concern everyday concepts, e.g. papu "bean", sini "(n.) blue" and pappi "priest". Notably, a few religious words such as Raamattu ("Bible") are borrowed from Russian, which indicates language contact preceding the Swedish era. This is mainly believed to be result of trade with Novgorod from the 9th century on and Russian Orthodox missions in the east in the 13th century.

Most recently, and with increasing impact, English has been the source of new loanwords in Finnish. Unlike previous geographical borrowing, the influence of English is largely cultural and reaches Finland by many routes, including international business, music, film and TV (foreign films and programmes, excluding ones intended for a very young audience, are shown subtitled), literature, and, of course, the Web – this is now probably the most important source of all non-face-to-face exposure to English.

The importance of English as the language of global commerce has led many non-English companies, including Finland's Nokia, to adopt English as their official operating language. Recently, it has been observed that English borrowings are also ousting previous borrowings, for example the switch from treffailla "to date" (from Swedish, träffa) to deittailla from English "to go for a date". Calques from English are also found, e.g. kovalevy (hard disk). Grammatical calques are also found, for example, the replacement of the impersonal (passiivi) with the English-style generic you, e. g. sä et voi "you cannot", instead of ei voi "one cannot". This construct, however, is limited to colloquial language, as it is against the standard grammar.

However, this does not mean that Finnish is threatened by English. Borrowing is normal language evolution, and neologisms are coined actively not only by the government, but also by the media. Moreover, Finnish and English have a considerably different grammar, phonology and phonotactics, discouraging direct borrowing. English loan words in Finnish slang include for example pleikkari "PlayStation", hodari "hot dog", and hedari "headache", "headshot" or "headbutt". Often these loanwords are distinctly identified as slang or jargon, rarely being used in a negative mood or in formal language. Since English and Finnish grammar, pronunciation and phonetics differ considerably, most loan words are inevitably sooner or later calqued – translated into native Finnish – retaining the semantic meaning.

Neologisms

Some modern terms have been synthesised rather than borrowed, for example:

- puhelin "telephone" (from the stem "puhel-" "talk"+ instrument suffix "-in" to make "an instrument for talking")

- tietokone "computer" (literally: "knowledge machine" or "data machine")

- levyke "diskette" (from levy "disc" + a diminutive -ke)

- sähköposti "email" (literally: "electric mail")

- linja-auto "bus" (literally: route-car)

- muovi "plastic" (from muovata "to form or model, e.g. from clay", from the stem muov+ suffix "-i" to make "a substance, material or element for modeling or forming". The suffix "-i" would correspond to the instrument suffix "-in", but instead of instrument in this case rather a substance, material or element that can be used.

Neologisms are actively generated by the Language Planning Office and the media. They are widely adopted. One would actually give an old-fashioned or rustic impression using forms such as kompuutteri (computer) or kalkulaattori (calculator) when the neologism is widely adopted.

Loans to other languages

Orthography

Finnish is written with the Swedish variant of the Latin alphabet that includes the distinct characters Ä and Ö, and also several characters (b, c, f, q, w, x, z and å) reserved for words of non-Finnish origin. The Finnish orthography follows the phoneme principle: each phoneme (meaningful sound) of the language corresponds to exactly one grapheme (independent letter), and each grapheme represents almost exactly one phoneme. This enables an easy spelling and facilitates reading and writing acquisition. The rule of thumb for Finnish orthography is: write as you read, read as you write. However, morphemes retain their spelling despite sandhi.

Some orthographical notes:

- Long vowels and consonants are represented by double occurrences of the relevant graphemes. This causes no confusion, and permits these sounds to be written without having to nearly double the size of the alphabet to accommodate separate graphemes for long sounds.

- The grapheme h is sounded slightly harder when placed before a consonant (initially breathy voiced, then voiceless) than before a vowel.

- Sandhi is not transcribed; the spelling of morphemes is immutable, e.g. tulen+pa /tulempa/.

- Some consonants (v, j, d) and all consonant clusters do not have distinctive length, and consequently, their allophonic variation is typically not specified in spelling, e.g. rajaan /rajaan/ (I limit) vs. raijaan /raijjaan/ (I haul).

- Pre-1900s texts and personal names use w for v. Both correspond to the same phoneme, the labiodental approximant /ʋ/, a v without the fricative ("hissing") quality of the English v.

- The letters ä [æ] and ö [ø], although written as umlauted a and o, do not represent phonological umlauts, and they are considered independent graphemes; the letter shapes have been copied from Swedish. An appropriate parallel from the Latin alphabet are the characters C and G (uppercase), which historically have a closer kinship than many other characters (G is a derivation of C) but are considered distinct letters, and changing one for the other will change meanings.

Although Finnish is almost completely written as it is spoken, there are a few differences:

- The n in nk is a velar nasal, as in English. As an exception to the phonetic principle, there is no g in ng, which is a long velar nasal as in English singalong.

- Sandhi phenomena such as the gemination between words or the change 'n+k' to [ŋk] is not marked in writing.

- The double consonant in clitic is marked as a single consonant.

- Only comparative and superlative adjectives the letter m is used like in speech in word like parempi, but in other similar cases the letter n is used, like in onpa

- The /j/ after the letter i is very weak or there is no /j/ at all, but in writing it is used; for example: urheilija. Indeed, the j is not used in writing words with consonant gradation (like aion and some other (like läksiäiset))

- In speech there is no difference between the use of /i/ in words (like ajoittaa, but ehdottaa), but in writing there are quite simple rules: The i is written in forms derived from words that consist two syllables and end in an or ä (sanoittaa, "to write song-lyrics", from sana, "word"), and in words that are old-stylish (innoittaa). The i is not written in forms derived from words that consist two syllables and end in o or ö (erottaa "to discern, to differentiate" from ero difference), words which do not clearly derive from a single word (hajottaa can be derived either from the stem haja- seen in such adverbs as hajalle, or from the related verb hajota), and in words that are descriptive (häämöttää) or workaday by their style (rehottaa)

When the appropriate characters are not available, the graphemes ä and ö are usually converted to a and o, respectively. This is common in e-mail addresses and other electronic media where there may be no support for characters outside the basic ASCII character set. Writing them as ae and oe, following German usage, is rarer and usually considered incorrect, but formally used in passports and equivalent situations. Both conversion rules have minimal pairs which would no longer be distinguished from each other.

The sounds š and ž are not a part of Finnish language itself and have been introduced by the Finnish national languages body for more phonologically accurate transcription of loanwords and foreign names. For technical reasons or convenience, the graphemes sh and zh are often used in quickly or less carefully written texts instead of š and ž. This is a deviation from the phonetic principle, and as such is liable to cause confusion, but the damage is minimal as the transcribed words are foreign in any case. Finnish does not use the sounds z, š or ž, but for the sake of exactitude, they can be included in spelling. (The recommendation cites the Russian play Hovanštšina as an example.) Many speakers pronounce all of them s, or distinguish only between s and š, because Finnish has no voiced sibilants.[22]

The language may be identified by its distinctive lack of the letters b, c, f, q, w, x, z and å.

Language example

|

Hyväntahtoinen aurinko katseli heitä. Se ei missään tapauksessa ollut heille vihainen. Kenties tunsi jonkinlaista myötätuntoakin heitä kohtaan. Aika velikultia. — Väinö Linna: The Unknown Soldier; these words were also inscribed in the 20 mk note. (Translation: "The benevolent sun watched them, by no means angrily. Perhaps it even felt some compassion towards them. Good old boys.") |

| ||||

Basic greetings

- (Hyvää) huomenta – (Good) morning

- (Hyvää) päivää – (Good) afternoon (literally "Good day")

- (Hyvää) iltaa – (Good) evening

- Hyvää yötä / Öitä! – Good night / "Night!"

- Terve! / Moro!/Moi! – Hello!

- Hei! / Moi! – Hi!

- Heippa! / Moikka! / Hei hei! / Moi moi! – Bye!

- Nähdään! – See you later! (lit. the passive form of the word "nähdä", "to see", but usually described as "we see.")

- Näkemiin – Goodbye (Literally "Till (I)/we see (each other)".

"Näkemiin" comes from the word "näkemä" ("sight"). Literally "näkemiin" means "Until seeing (again)" - Hyvästi – Goodbye / Farewell

- Hauska tutustua! – Nice to meet you.

- Kiitos – Thank you

- Kiitos, samoin – "Thank you, the same to you" / Likewise (as a response to "well-wishing")

- Mitä kuuluu? – How are you / How are you doing? (Not used among strangers, literally "What are you hearing?")

- Kiitos hyvää! – I'm fine, thank you.

- Tervetuloa! – Welcome!

- Anteeksi – Sorry / Excuse me

Important words and phrases

- kyllä – yes

- joo – yes (informal)

- ei – no

- en – I will not / I do not

- minä, sinä, hän (se) – I, you, he/she(it)

- me, te, he (ne) – we, you (two or more), they

- (minä) olen – I am

- (sinä) olet – you are (singular)

- hän on - he/she is

- (te) olette – you are (plural)

- (minä) en ole – I am not

- (sinä) et ole – You are not

- hän ei ole - he/she is not

- yksi, kaksi, kolme – one, two, three

- neljä, viisi, kuusi – four, five, six

- seitsemän, kahdeksan – seven, eight

- yhdeksän, kymmenen – nine, ten

- yksitoista, kaksitoista, kolmetoista – eleven, twelve, thirteen

- sata, tuhat, miljoona – hundred, thousand, million

- (minä) rakastan sinua – I love you

- kiitos – thank you

- anteeksi – forgive me, excuse me, sorry

- voitko auttaa – can you help

- apua! – help!

- voisit(te)ko auttaa – could you help

- missä ... on? – where is ...?

- olen pahoillani – I'm sorry (apology)

- otan osaa – My condolences

- onnea – good luck

- totta kai/tietysti/toki – of course

- pieni hetki, pikku hetki, hetkinen – one moment please!

- odota – wait

- missä on vessa? – where is the bathroom?

- Suomi – Finland

- suomi/suomen kieli – Finnish language

- suomalainen – (noun) Finn; (adjective) Finnish

- En ymmärrä – I don't understand

- (Minä) ymmärrän – I understand

- ¹Ymmärrät(te)kö suomea? – Do you understand Finnish?

- ¹Puhut(te)ko englantia? – Do you speak English?

- Olen englantilainen / amerikkalainen / kanadalainen / australialainen / uusiseelantilainen / irlantilainen / skotlantilainen / walesilainen / ranskalainen / saksalainen / kiinalainen / japanilainen / ruotsalainen – I am English / American / Canadian / Australian / New Zealander / Irish / Scottish / Welsh / French / German / Chinese / Japanese / Swedish

- ¹Olet(te)ko englantilainen? – Are you English?

- Missä (sinä) asut/¹Missä (te) asutte? – Where do you live?

¹ -te is added to make the sentence formal (T-V distinction). Otherwise, without the added "-te", it is informal. It is also added when talking to more than one person. The transition from second-person singular to second-person plural (teitittely) is a politeness pattern, advised by many "good manners guides". Elderly people, especially, expect it from strangers, whereas the younger might feel it to be too formal to the point of coldness. However, a learner of the language should not be excessively concerned about it. Omitting it is (almost) never offensive, but one should keep in mind that on formal occasions this custom may make a good impression.

See also

References

- Notes

- ↑ Finnish at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ↑ О государственной поддержке карельского, вепсского и финского языков в Республике Карелия (in Russian). Gov.karelia.ru. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- ↑ Finnish is one of the official minority languages of Sweden

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Finnish". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ ThisisFINLAND-Who is afraid of Finnish ?

- ↑ "Defense Language Institute" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 19, 2012. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- 1 2 3 Statistics Finland. "Tilastokeskus – Population". Stat.fi. Retrieved 2011-12-17.

- ↑ Konvention mellan Sverige, Danmark, Finland, Island och Norge om nordiska medborgares rätt att använda sitt eget språk i annat nordiskt land, Nordic Council website. Retrieved on April 25, 2007.

- ↑ 20th anniversary of the Nordic Language Convention, Nordic news, February 22, 2007. Retrieved on April 25, 2007.

- ↑ Laakso, Johanna (November 2000). "Omasta ja vieraasta rakentuminen". Archived from the original on 2007-08-26. Retrieved 2007-09-22.

Recent research (Sammallahti 1977, Terho Itkonen 1983, Viitso 1985, 2000 etc., Koponen 1991, Salminen 1998 etc.) operates with three or more hypothetical Proto-Finnic proto-dialects and considers the evolution of present-day Finnic languages (partly) as a result of interference and amalgamation of (proto-)dialects.

- ↑ Wulff, Christine. "Zwei Finnische Sätze aus dem 15. Jahrhundert". Ural-Altaische Jahrbücher NF Bd. 2 (in German): 90–98.

- ↑ http://www.kotus.fi/files/1291/Kielen_aika.pdf

- ↑ "Svenskfinland.fi". Svenskfinland.fi. Retrieved 2012-04-05.

- ↑ Rekunen, Jorma; Yli-Luukko, Eeva; Jaakko Yli-Paavola (2007-03-19). "Eurajoen murre". Kauden murre (online publication: samples of Finnish dialects) (in Finnish). Kotus (The Research Institute for the Languages of Finland). Retrieved 2007-07-11.

"θ on sama äänne kuin th englannin sanassa thing. ð sama äänne kuin th englannin sanassa this.

- ↑ Kuusi, Matti; Anttonen Pertti (1985). Kalevala-lipas. SKS, Finnish Literature Society. ISBN 951-717-380-6.

- ↑ "Suomen murteet". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2008-01-03.

- ↑ Archived December 30, 2005, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Hakulinen, Auli et al. (2004): Iso suomen kielioppi. SKS:n toimituksia 950. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. ISBN 951-746-557-2. 1,600 pages

- ↑ Yleiskielen ts:n murrevastineet Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Kirmse, U; Ylinen, S; Tervaniemi, M; Vainio, M; Schröger, E; Jacobsen, T (2008). "Modulation of the mismatch negativity (MMN) to vowel duration changes in native speakers of Finnish and German as a result of language experience.". International Journal of Psychophysiology. 67 (2): 131–143. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2007.10.012.

- ↑ Häkkinen, Kaisa. Suomalaisten esihistoria kielitieteen valossa (ISBN 951-717-855-7). Suomalaisen kirjallisuuden seura 1996. See pages 166 and 173.

- ↑ "Kirjaimet š ja ž suomen kielenoikeinkirjoituksessa". KOTUS. 1998. Retrieved 2014-06-29.

External links

| Finnish edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |