Ständchen (Schubert)

Ständchen D. 889, (known in English by its first line Hark, hark, the lark or Serenade) is a lied for solo voice and piano by Franz Schubert, composed in July 1826 in Währing, then a village north-west of the walls of Vienna, now a suburb. The lied is a setting of the 'Song' in Act II, Scene 3 of Shakespeare's Cymbeline. Schubert died aged only 31 in 1828, and the song was first published posthumously by Anton Diabelli in 1830. The song in its original form is relatively short, and two further verses by Friedrich Reil were added to Diabelli's second edition of 1832.

Although the German translation which Schubert used has been attributed to August Schlegel (apparently on the basis of various editions of Cymbeline bearing his name published in Vienna in 1825 and 1826),[2] the text is not exactly the same as the one which Schubert set: and this particular adaptation of Shakespeare had already been published as early as 1810 as the work of Abraham Voß, and again — under the joint names of A. W. Schlegel and J. J. Eschenburg — in a collected Shakespeare edition of 1811.

This 1810 version by Abraham Voß, and various other adaptations of Cymbeline, bear remarkable similarities to an earlier translation of Cymbeline by Eschenburg, first published in 1777.

Works by other composers appearing in 1826 included Hector Berlioz' Symphonie Fantastique; Mendelssohn's incidental music to A Midsummer Night's Dream; and Weber's opera Oberon had its first performance at the Covent Garden, London.

Critical commentary

Schubert's biographer John Reed (1909–1999)[3] says that the song "celebrates the universality two of the world's greatest song-writers."[4] Richard Capell in his survey of Schubert's songs, called the Ständchen "very pretty" but "a trifle overrated [...] the song is hardly one to be very fond of. Not a lifetime of familiarity with it can bridge the gap that yawns between the Elizabethan's verse and the Austrian's tune."[5] On the other hand, while discussing the variorum readings of Shakespeare's play, Howard Furness refers to "the version which Schubert sets to peerless music",[n 2] and Sir George Grove describes how "that beautiful song, so perfectly fitting the words, and so skilful and happy in its accompaniment, came into perfect existence."[6]

Genesis of the lied

_b_066.jpg)

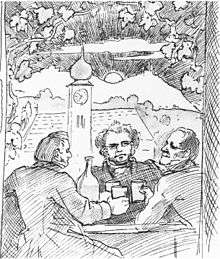

A story about the song's creation was recounted by a boyhood friend of Schubert to the composer's biographer, Heinrich Kreissle von Hellborn[7] in his Life of Franz Schubert.[8] Sir George Grove relates Kreissle's anecdote verbatim,[n 3] although it has been called "pretty, but untrue",[9] "apocryphal",[10] and "legend".[11][12]

Herr Franz Doppler (of the musical firm of Spina)[n 4] told me the following story in connection with the Ständchen:——"One Sunday, during the summer of 1826, Schubert with several friends was returning from Pötzleinsdorf to the city, and on strolling along through Währing, he saw his friend Ludwig Titze[n 5] sitting at a table in the garden of the 'Zum Biersack'.[13] The whole party determined on a halt in their journey. Tietze had a book lying open before him, and Schubert soon began to turn over the leaves. Suddenly he stopped, and pointing to a poem, exclaimed, "such a delicious melody has just come into my head, if I but had a sheet of music paper with me."[14] Herr Doppler drew a few music lines on the back of a bill of fare, and in the midst of a genuine Sunday hubbub, with fiddlers, skittle players, and waiters running about in different directions with orders, Schubert wrote that lovely song.[8]

Maurice Brown, in his critical biography of Schubert, partially debunks the story, showing that the garden of the 'Zum Biersack' in Währing was next door to that of the poet Franz von Schober, and that Schubert spent some time there in the summer of 1826 with the painter Moritz von Schwind, although not necessarily staying overnight more than once or twice.[15] Brown thinks that Doppler may have been confused about the place where the incident took place. Brown in his book only mentions Titze twice in passing, however, and not in connection with the story of the menu.[n 6]

The English text

The German translation which Schubert set has the same metre/rhythm as Shakespeare's lyric, which allows the music to be sung to the original English words.

Shakespeare

The Song from Cymbeline, Act II, Scene 3, is full of compressed meaning and metaphor. It is considered at length and in detail in the posthumously published variorum edition of the First Folio[20] by Howard Furness.[n 7] The following three lines are particularly dense with allusion:

Cite error: There are <ref group=n> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=n}} template (see the help page).

These phrases are explained by William Warburton (sometime Bishop of Gloucester) in a succinct paraphrase in his 1747 edition of Alexander Pope's version of Shakespeare: represented by the mythical horses which pull Phoebus' fiery chariot, "the morning sun dries the dew which lies in the cups of flowers."[21]

The stanza or stave of this song is one of four fourteen-syllable verses, and a refrain.[22]

Song

Hearke, hearke, the Larke at Heauns gate ſings,

and Phoebus gins arise,

His Steeds to water at thoſe Springs

on chalic'd Floweres that lyes:

And winking Mary-buds begin to ope their Golden eyes

With euery thing that pretty is, my Lady sweet ariſe:

Ariſe, ariſe.

(Shakespeare, First Folio, 1623)[1]

For a modern English version of the text, see § Ex. 1 below.

- ^ "Shakespeare's First Folio – Cymbeline". Leeds University Library: The Brotherton First Folio digital resource. p. 377. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

18th century editors

Alexander Pope tampered with the division of Shakespeare's lines as they stood in the First Folio.[23] Sir Thomas Hanmer, 4th Baronet, (another 'improver' of Shakespeare) added his "rustick and antequated" rhyming emendations to the new caesuras;[24] thus the 'pretty bin' which found its way into many editions of Shakespeare, and into numerous Schubert editions in English.[24][25]

Song

Hark , hark , the lark at heav'n's gate ſings ,

And Phoebus 'gins ariſe ,

His ſteeds to water at thoſe ſprings

Each chalice'd flower ſupplies :

And winking Mary-buds begin

To ope their golden eyes,

With all the things that pretty bin ;

My Lady ſweet , ariſe :

Ariſe , ariſe .(Sir Thomas Hanmer, 1747)[26]

Furness confesses that "It is not easy to recall any needless emendation of Shakespeare which is become so imbedded in the popular mind as this substitution by Hanmer of bin. This is due partly to the mistaken idea that a rhyme is needed to 'begin', partly because Hanmer's was the edition of the nobility and gentry, partly, I think, because 'bin' is adopted in the version which Schubert sets to peerless music."[24] A quarrel between Hanmer and Warburton[27] over an entry in the Encyclopedia Britannica seems to have been a storm in a teacup, according to The Monthly Review.[28][29]

Song title

In German translations of Cymbeline, the short lyric which Schubert set to music is simply titled Lied ('Song'). Schubert's title, Ständchen, is usually translated into English as Serenade, which itself derives from fr:le soir; this can be slightly disquieting for an English speaker, since this word specifically refers to a musical performance in the evening; the early hours are reserved for the 'aubade' (from fr:l'aube). The words of the poem, and its context within the play, indicate that is unquestionably to be sung in the morning: if there were any doubt, the lines which immediately precede the text of the 'Song' include this snippet of dialogue:

Cloten: It's almost morning, is't not?

First Lord: Day, my lord.

The German word 'Ständchen' is unspecific about the time of the homage, and lacks the connotations of the gloaming of the English equivalent.[30] As others have pointed out,[31] and as Furness in his 'Variorum Edition' of Cymbeline makes abundantly clear, "This present song is the supreme crown of all aubades..."[32] The Schirmer edition of Liszt's transcription for solo piano clarifies the context with the title of Morgenständchen ('morning serenade'),[33] and the German title of Schubert's song would be more accurately rendered in English as Aubade.

The German text

Background

Attribution

Schubert's song was published posthumously as 'Ständchen von Shakespeare' in part seven of Diabelli's first edition of Schubert's songs (Schubert 1830, p. 3). See § Ex. 2 below. Two further verses were added by Friedrich Reil (1773–1843) for the second edition (Schubert 1832); the Peters edition in the original key retains the attribution to 'Shakespeare'.[34]

Both the Breitkopf & Härtel edition of 1894–95, and in the Peters edition for low voice credit A. W. Schlegel with the words.[34] Otto Deutsch in his 1951 Schubert Thematic Catalogue entry for D889 also gives "deutsch von August Wilhelm Schlegel", with no further details.[35]

Various German translations of Cymbeline appeared from the late eighteenth century onwards; many of them are listed in Blinn & Schmidt 2003.[n 8] The attribution to Schlegel appears to be based on a translation of Cymbeline bearing his name in a collected edition – by multiple translators – of Shakespeare's plays, published in Vienna in 1825 (sometimes called the 'Wiener Shakespeare-Ausgabe' or 'Vienna Shakespeare edition').[4][n 9] This edition appeared in at least four slightly differing printings from two publishers; three of the volumes containing Cymbeline bore Schlegel's name on the title page, although a fourth appeared anonymously.

The following sections attempt to show that while the greater majority of the lines of the Ständchen are very nearly the same as in a number of previous adaptations of Shakespeare by other hands, the text which Schubert used is not that of the 'Schlegel' Cymbeline of 1825. Schubert, like many other composers, sometimes altered the words he was setting, even drastically;[36] but the similar nature of the small variations between all the versions below, none of which are exactly reproduced by Schubert, indicates that he may have been using some other edition.

J. J. Eschenburg, 1777 and 1805

Ignoring all other differences in the rest of Cymbeline, the text of the 'Lied' itself in Act II which Schubert set survives relatively unchanged from a translation which J. J. Eschenburg had published in 1777. [37][38][n 10] See § Ex. 4 below. The 1777 edition was revised in 1805, with a slightly different version of the 'Lied'. See § Ex. 5

Abraham Voß, 1810

Apart from the first line – which is considerably altered – and a few other smaller changes, Eschenburg's text of the Lied appears almost verbatim in an 1810 verse translation of Cymbeline made by Abraham Voß. This was published by J. G. Cotta along with Macbeth by his brother Heinrich Voß in Tübingen[39][40][n 11][n 12] See § Ex. 6 beloww.

- The Voß family and Shakespeare

The 'collaboration' between the Voß brothers began as early as 1806, when Heinrich moved from Weimar (where he had been with Goethe and Schiller) to join his family in Heidelberg where they had moved from Jena in July 1805. Their father, Johann Heinrich Voß had already published translations of two Shakespeare plays[41] made under the auspices of Schiller and Goethe respectively.[42] Heinrich continued his Shakespeare translations in Heidelberg, soon to be joined in this undertaking by Abraham. Between 1810 and 1815, the two sons published three volumes of Shakespeare's plays, none of which had been rendered in German by Schlegel.[43] The first volume published during these years in Heidelberg was Heinrich's translation of Macbeth and Abraham's rendering of Cymbeline.[40][44][n 13] Heinrich Voß knew Martin Wieland, one of the first translators of Shakespeare into German, whose first attempts were first published in 1762–66.[45][46]

According to Drewing, "Heinrich Voß thought Abraham was weak, and it is not easy to see how far and on what basis Abraham and Heinrich collaborated"[47] An unpublished letter from Heinrich to a friend, Bernhard Rudolf Abeken (3 July 1816), complains about the help which Abraham required with his translations.[48] Another letter to Abeken illustrates the extent to which Abraham relied on Heinrich's help: "But said frankly: Abraham's translation in its many merits [...] is too faithful to still be faithful/true. In such verses as ... I do not find Shakspeare again/afresh, who in his construction is mostly very easy; wherever it is not it, it is daring ... Then again, Abraham's expressions are often too low; rascal, scoundrel occur very often ... Make him do it again, carefully."[48][n 14] The first volume by Johann Heinrich Voß and his sons appeared in 1818.[49] Heinrich Voss died in 1822 of dropsy aged 43, and Abraham and his father Johann Heinrich Voss completed the work over a number of years. Abraham's earlier version of the 'Lied' was considerably revised for the 1828 edition prepared by Heinrich and their father.[50] See § Ex. 8 below for a comparison, although it appeared in 1828 after Schubert had written the Ständchen.

The Voß's modernising treatment of Shakespeare's often complex and daring Elizabethan language appealed to 19th-century German sensibilities, portraying Shakespeare as a modern German writer using 'correct' and up-to-date forms of language. According to Drewing, "...the aim of Johann Heinrich (the father) and Heinrich Voß was precisely not to make Shakespeare sound like a 19th century German poet, but to convey the essence of an alien work; and that any departures from conventional literary German are intentional and represent an attempt not to reduce the sense of otherness in the text." [emphases added.][51]

For all its merits, the Voß Shakespeare was considered incompatible with contemporary taste, whereas the so-called 'Schlegel-Tieck' edition conformed with it.[52] "What the German public demands is a Shakespeare who speaks 'that kind of [German] which he would have spoken had he lived in [Germany], and had written to this age' – everything, in fact, which the Voß Shakespeare is and does not."[53] This attitude was in keeping with the 'contemporary' approach towards translation of which Goethe was a proponent.[n 15]

- 'Schlegel-Tieck' (1825-1833)

The Voß's work was unfavourably compared to the so-called Schlegel-Tieck complete Shakespeare edition in verse translation, which appeared at around the same time. Although Ludwig Tieck's name appears on the title page, he was only associated with this edition in a purely advisory capacity with responsibility for editing and compiling annotations. His daughter Dorothea Tieck and Wolf Graf von Baudissin had a considerable hand in supplying the so-called Schlegel-Tieck translation.[54] Cymbeline was translated by Tieck's daughter Dorothea,[55] although Schlegel was apparently unhappy with the first new edition ('Schlegel-Tieck' 1833) and repudiated Tieck's revisions; later editions (1839–41) restored Schlegel's translations and notes.[56] See § Ex. 9 below for comparison, which appeared in 1833 after Schubert's death in 1828.

Schlegel and Eschenburg, 1811

Abraham Voß's 1810 translation of Cymbeline was published again in 1811 in a complete edition, with the names of A. W. Schlegel and J. J. Eschenburg on the title-page.[57] The text of the 'Song' is the same as § Ex. 5 below.

'Vienna Shakespeare edition', 1825–1827

.png)

A collected German edition of Shakespeare's plays in verse ("in Metrum des Original") – by multiple translators – was published in Vienna in 1825 and 1826 (sometimes called the 'Wiener Shakespeare Ausgabe' or 'Vienna edition'). It was commissioned by the "indefatigable" printer and lithographer Joseph Trentsensky,[58] one of whose employees was the lithographer Josef Kriehuber. Some translations were newly done for this 'Vienna edition', including Antony and Cleopatra and The Two Gentlemen of Verona by Eduard Bauernfeld (from which Schubert took his other two Shakespeare songs Trinklied, D888 and Was ist Silvia, D981):[58] other translations in the Vienna edition had been previously published. This collection appeared in at least four slightly differing versions from two publishers, which should perhaps be called the 'Vienna editions'.[n 16]

The German words which Schubert used for the Ständchen are usually attributed to August Schlegel.[35][n 17] His name appears on the title pages of three of the Cymbelines, but is strangely omitted on a fourth. See § Notes. Whatever Schlegel's involvement in the 1825–6 publications,[n 18] there are small but significant differences between the Vienna editions and Schubert's manuscript. See § Ex. 7 beloww. (C180)

Summary

The text of the 'Lied' from Shakespeare's Cymbeline which Schubert set contains considerable similarities to the very first translations of Shakespeare into German by J. J. Eschenburg in 1777. The version which Schubert set differs only very slightly in its orthography ('Ätherblau' etc.) from that of Abraham Voß ('Aetherblau', etc.), which dates from at least 1810. This 'Ätherblau' version was published in 1812 under the names of A. W. Schlegel and J. J. Eschenburg, and then in at least four slightly differing printings of the 'Vienna Shakespeare Editions' in 1825 and 1826, with and without Schelegel's name on the title-page.

Versions of the text

1. Modern English version |

2. Schubert MS, 1826; 1st edition, 1828

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Schubert manuscripts

The earliest surviving Schubert autograph MS[59][n 19] is in the Wienbibliothek im Rathaus. It consists of four Lieder (of which the Ständchen is the second) in a pocket-sized MS book with staves hand-ruled by Schubert.[31] At of the top of the first page, in Schubert's hand, is written: Währing, July 1826, followed by his signature.

- "Trinklied", D888 – (Antony & Cleopatra, Act II, Scene 7 – trans. Eduard Bauernfeld & Ferdinand Mayrhofer von Grünbühel)

- "Ständchen", D889 ("Hark, hark, the lark") - (Cymbeline, Act II, Scene 3 - possibly not trans. by Schlegel, whoever it turns actually out to be by... lol the search continues...)

- "Hippolits Lied", D890 - by Friedriech von Gerstenberg[n 20]

- Gesang, D891 ("Was ist Sylvia?") – (Two Gentlemen of Verona, Act IV, Scene 2 – trans. Bauernfeld alone)

The text of the MS is exactly reproduced in the first published edition of the song (Schubert 1830, pp. 14–15 [16–17]), except for some very minor punctuation.[n 21] Fair autograph copies of two of the four songs in the Vienna Library MS ("Trinklied" and "Was ist Silvia?") are held in the Hungarian National Library (National Széchényi Library).[60]

Arrangements

Ständchen has been arranged for various instrumental combinations, including Franz Liszt's transcription for solo piano, published by Diabelli in 1838 as no. 9, Ständchen von Shakespeare, of his 12 Lieder von Franz Schubert, S.558.[61]

References

- Notes

- ↑ Bauernfeld, with F Mayrhofer von G, translated The Two Gentlemen of Verona, from which Schubert set the words "Who is Sylvia?".

- ↑ See Furness 1913, pp. 126–129 for a fully comprehensive, dazzlingly learned, concise and detailed discussion of these lines.

- ↑ (Grove 1951, p. 141). If Grove had had doubts about the story he would probably have expressed them; elsewhere he cites Thayer "who allows me to say he sees no reason to question" an account of a different matter by the less reliable Anton Schindler (Grove 1951, p. 200).

- ↑ C. A. Spina published a number of first editions of Schubert, and owned many Schubert manuscripts which he lent to Brahms to study and copy (Clive 2006, p. 439).

- Joseph Doppler (dates?) is evidently meant here, and not his son Franz Doppler (born in 1821, and thus aged 7-ish when Schubert died in 1828). Joseph Doppler is referred to a number of times in volume 1 of von Hellborn's book as the manager at the publishing house of Spina, which later took over the music businesses of Diabelli, Artaria and others. Doppler, (who played a number of instruments – viola, oboe, clarinet, bassoon?), had known Schubert from boyhood and played quartets in the Schubert house.<-- did he also go to the Convictschule? --> For example: "To the existing quartett of performers were added Herr Josef Doppler (foreman and chief manager of the musical establishment of C. A. Spina), who had been intimate with Schubert from boyhood..." (von Hellborn 1865, p. ???).

- ↑ Titze (who died in 1850) was a popular singer with a sympathetic and highly trained tenor voice, who gave a number of first performances of Schubert's songs. "Schubert kept us waiting for him [at a Schubertiade] in vain...but...Titze sang many of his songs so touchingly and soulfully that we did not feel his absence too painfully." (Brown 1958, p. 282).

- ↑ Thoughts:

- The earliest surviving manuscript by Schubert is sadly not on the back of a menu, it's the second in a group of four MS songs D888–91 in a pocket-sized autograph MS booklet with pencil-ruled lines (according to Graham Johnson), which includes Schubert's three Shakespeare songs plus Hippolits Gesang. See § Schubert manuscripts below. Hellborn in passing mentions the Trinklied D888 (the MS of which also appears in the same booklet), but not to connect it with the anecdote about the Ständchen's creation.

- Sir George Grove, in Beethoven – Schubert – Mendelssohn (Grove 1951, p. 141n), appears to know of two other separate manuscripts of "Trinklied" and "Sylvia"; he says the Drinking Song is marked 'Währing, July 26', and the second, 'July 1826'. The "An Sylvia" article refers to Reed[16] but introduces some errors.

- Although the earliest surviving MS of Ständchen has all the appearance of a first draft, the MS of 'Gesang' ("Was ist Sylvia", D891) – which is the last song in the same MS pocket book – betrays several signs of being a second draft of the vocal melody, above a piano accompaniment being written out for the first time.[11]

- The questions of exactly where, and on what medium the music was written continues to form a fruitful subject for future musicological research: Joseph Doppler may, of course, have been entirely mistaken about everything. Nevertheless, whatever the circumstances of the song's creation, there seems to be less dispute that it centres around Ludwig Titze and the book he was reading: and why bother to mention him if it were essentially untrue (pace the ghost of Anton Schindler), and it was some other person who had provided the book?

- A similar tale is told of the composer Benedict Randhartiger (1802–1893)[17][18] (whose brother Joseph—like Schubert—was a torch-bearer at Beethoven's funeral procession), and the creation of Die schöne Müllerin.[19]

- ↑ "Angels and ministers of grace, defend us!" (Hamlet → Act 1, Scene 4) is the studied reaction of Furness when contemplating James Murray's article on the word 'be' in the OED, during his comprehensive, learned and mildly hilarious discussion of these six or eight lines of Shakespeare's play. If you like your footnotes to take up at least 90% of the page, this is the book for you. (Furness 1913, pp. 126–9).

- ↑ The German pronunciation of 'Cymbeline' rhymes fairly closely with 'Thumbelina' in English. The German title Cymbelin is a more accurate rendering of the English pronunciation of the king's name.

- ↑ Hmmz, although the 1995 Dover edition of Deutsch catalogue incorporates scholarship updates since 1951, I imagine (hah!) that Reed (1997) would have reflected any difference of ideas about the text's authorship...

- ↑ "A revision of Wieland's translation to which is added Heinrich V, Heinrich VI, Richard III, Heinrich VIII, Zähmung eines bösen weibes, Die lustigen weiber von Windsor, Verlorne liebesmühe, Ende gut, alles gut, Troilus und Cressida, Coriolan, Cymbeline and Titus Andronicus." Source: Stanford University Library catalogue entry, accessed 20 December 2015

- ↑ The other plays in this edition include Macbeth (1810, along with Cymbeline); The Winter's Tale and Coriolanus (1812); and Antony and Cleopatra, The Merry Wives of Windsor and The Comedy of Errors (1815). Listed under number C110 in Blinn & Schmidt 2003, pp. 29–30.

- ↑ This 1810 version of Cymbeline was revised somewhat for the 1828 edition (part of the complete 3-Voß Shakespeare, C130 in Blinn & Schmidt 2003, pp. 29–30); the text of the 'Lied' itself is rendered differently, although the play as a whole still retains much of the 1810 text.

- ↑ Heinrich makes mention of his brother's near completion of Cymbelin in an undated letter from late 1808, and Heinrich offers both Macbeth and Cymbelin to Cotta for publication in a letter dated 4 February 1809. See M. Fehling (Hrsg.), Briefe an Cotta. Das Zeitalter Goethes und Napoleons 1794–1815 (Stuttgart, 1925) (in German), p. 308, cited in Drewing 1993, pp. 88, 269n.

- ↑ 'Aber offenherzig gesagt: Abrahams Uebersetzung bei ihren vielen Verdiensten [...] ist zu getreu, um noch getreu zu sein. In Versen wie ... finde ich Shakspeare nicht wieder, der in Construktionen meistens so sehr leicht ist; wo er's nicht ist, ist's Kühnheit ... Dann sind Abrahams Ausdrücke oft zu niedrig; Schuft, Lump kommt sehr oft vor...Mach ihn doch darauf einmal aufmerksam'.

- ↑ From the introduction to an 1834 English translation of Faust: 'Of the two modes of translating I certainly prefer that "which," in the words of Goethe, "requires that the author of a foreign nation be brought to us in such manner as we may regard him as our own," – to that other – "which, on the contrary, demands of us that we transport ourselves over to him, and adopt his situation, his peculiarities." ' (Faust: A Tragedy tr. David Syme, 1834, p. iv.)

- ↑ There are at least four versions of the 'Vienna Shakespeare editions': 1st edition as individual plays (1825); expanded in one volume with additions (1826); further individual supplements (1827) (all pub. Sollinger); unillustrated edition (Sammer), (1826). Although all the individual volumes containing Cymbeline contain the same text, they are listed here for the sake of completeness (not necessarily in the actual order of publication). For the purposes of this article only, the 1826 editions are numbered 1826a–c. NB Blinn & Schmidt 2003, p. 29

- 1. 1825. Each work in the 'Vienna edition' was published separately in 1825, including Cymbeline (vol. 26), with Schlegel's name and a lithographed vignette on the title page.

- Schlegel, August Wilhelm [more likely by Abraham Voß] (1825). Cymbeline / von A. W. Schlegel / Titel und Vignetten / lithographiert bei Joseph Trentsensky /in Wien. William Shakespeare's saemmtliche Dramatische Werke / übersetzt in Metrum des Originals / Bändchen XXVI (in German). Vienna: Drück und Verlag von J. D. Sollinger. (Title page, p. 3.)

- 2. 1826a. The individual plays were collected in a one-volume edition in 1826, with a two-column format. The title page of Cymbeline in this volume (p. 603) lacks Schlegel's – or any other translator's – name, unlike all the other plays in this volume.

- William Shakespeare's saemmtliche dramatische Werke / übersetzt in Metrum des Originals / in einem Bande (in German). Vienna: Drück und Verlag von J. D. Sollinger / Titel und Vignetten / lithographiert bei Jos. Trentsensky. 1826.

- 3. 1826b, not in Blinn and Schmidt? The above edition was expanded as a 'Complete edition in one volume', of the plays and poems, with a supplement containing a life of Shakespeare, together with critical remarks and notes. Further supplements to this edition appeared in 1827.

- William Shakespeare's sämmtliche Dramatische Werke / und / Gedichte. / Übersetzt in Metrum des Originals. / Vollständige Ausgabe in Einem Bande (in German). Vienna: Drück und Verlag von J. D. Sollinger. / lithog. bei Jos. Trentsensky in Wien [title illustration only]. 1826. (Title page: Cymbelin, von A. W. Schlegel, p. 598) NB Title page ('Vollständige Ausgabe in Einem Bande') is different to the following entry.

- 4. 1826c. Essentially a reprint of the preceding work, with the same pagination but with a different title-page, and no illustrations at all. C180 in Blinn & Schmidt 2003, p. 29.

- William Shakespeare's sämmtliche dramatische Werke / und / Gedichte. / Übersetzt in Metrum des Originals / in einem Bande nebst Supplement [...] (in German). Vienna: Zu haben bei Rudolph Sammer, Buchhändler / verlegt bei J. D. Solllinger. 1826. (NB This work appears as four separate volumes on Google Books. Part 4 begins with Othello: title page of Cymbeline on p. 598.) Bibliographical details from title page of part 1, beginning with The Tempest ('Der Sturm') and including Bauernfeld's Two Gentlemen of Verona ('Die beiden Edelleute von Verona'), from which Schubert set Was is Silvia, D. 891.

- 1. 1825. Each work in the 'Vienna edition' was published separately in 1825, including Cymbeline (vol. 26), with Schlegel's name and a lithographed vignette on the title page.

- ↑ Reed 1997, p. 394, who also says that Schubert used the 1825 Vienna edition (Schlegel 1825, p. 33 [38]). However, a careful comparison of the text of this particular edition with those of the Schubert MS and Diabelli's editions of 1830 and 1832 shows that they are not in fact quite the same. In fact, all the versions of the 'Lied' in the editions mentioned here (and more) contain variants which differ in one or more small but important ways from the Schubert setting: and none of them are exactly similar. It seems reasonable to conclude that unless he made the alterations himself, Schubert may have used an edition other than the 1825 Vienna edition bearing Schlegel's name. Also, Reed says that Friedrich Reil's two extra verses were written for the first edition (Schubert 1830), whereas they appeared in the 2nd edition of 1832 (Schubert 1832).

- ↑ "M.C. Lazenby sets down the aim of her doctoral dissertation as follows: The purpose of my investigation was to ascertain whether Schlegel had drawn from ... earlier translations and if so, to determine the nature and extent of his borrowing ... I found many instances of similarities, which, taken as a whole, constitute unimpeachable evidence that Schlegel was making frequent reference to both of the earlier translations. [i.e.to Wieland and Eschenburg]." See M.C. Lazenby, The Influence of Wieland and Eschenburg on Schlegel's Shakespeare Translation. Diss. Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, 1942, p. 9., cited in Drewing 1993, pp. 63, 260n

- ↑ Catalogue number LQH0248377 (previously MH 116/c [PhA 1176]) (Deutsch 1978?, p. 560).

- ↑ Previously attributed to Johanna von Schopenhauer (the philosopher's mother) who includes it in the 1st ed. of her novel Gabriele (Gabriele: Ein Roman in drei Theilen, pp 351–2) – later editions revealed her sources.

- ↑ Namely, the comma after du in the last line, which the 1832 edition (Schubert 1832) correctly omits, although it also removes the comma after "Phöbus". In the manuscript, Schubert appears to use a sort of rounded u sign (or more like a long horizontal bar rounded at the end), in order to distinguish clearly all instances of the letter u without umlaut (diaresis) from a ü. In "Was ist Sylvia?" he uses a vertical sign looking like a walking-stick to highlight the inserted bars of the piano accompaniment.

- Citations

- ↑ Woodford 2010, Google Books unpaginated preview.

- ↑ e.g. Reed 1997, p. 394

- ↑ Reid, Paul (17 January 2000). "John Reed". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- 1 2 Reed 1997, p. 394.

- ↑ Capell 1929, pp. 224–5.

- ↑ Grove 1951, p. 141.

- ↑ Kreissle von Hellborn, Heinrich. Grove, on Wikisource.

- 1 2 von Hellborn 1865, Vol. 2, pp. 75–76n [90–91].

- ↑ Dahms 1918, p. 227 [239].

- ↑ Johnson 1996b.

- 1 2 Capell 1929, p. 224.

- ↑ Brown 1958, pp. 241–2 [258–9].

- ↑ Zum Biersack. Vienna - now at Gentzgasse 31

- ↑ "Mir fällt da eine schöne Melodie ein, hätte ich nur Notenpapier bei mir!"

- ↑ Brown 1958, pp. 241-2 [258-9].

- ↑ p. 49,

- ↑ "Randhartiger: Lieder". CBDT. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ↑ Nederlandse Muziek uit heden en verleden vanaf de 17e eeuw (August 2003) Toonkunst Koor Nijmegen (in Dutch). Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ↑ "Benedict Randhartinger". New York Times. 11 January 1894. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ↑

- ↑ Pope & Warburton 1747, p. 236.

- ↑ Furness 1913, p. 129, citing Knight.

- ↑ See Pope's 6-volume edition of 1723/1725 (Pope 1723, p. 152)

- 1 2 3 Furness 1913, p. 129.

- ↑ For example, Vincent 1916, p. 101

- ↑ Hanmer 1744, p. 261.

- ↑ The Castrated Letter of Sir Thomas Hanmer

- ↑ The Monthly Review, Vol. 30, p. 252.

- ↑ Although some of his emendations of Shakespeare have been generally accepted, Samuel Coleridge called him "the thought-swarming, but idealess, Warburton". (Furness 1913, p. 122).

- ↑ "Ständchen". Das Digitale Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache (DWDS) (in German). Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- 1 2 Johnson 1996a.

- ↑ Furness 1913, p. 127.

- ↑ "12 Lieder von Franz Schubert, S.558/9. Morgenstandchen". G. Schirmer, n.d. Plate 2556. IMSLP. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- 1 2 Ständchen, D.889 (Schubert, Franz). IMSLP, accessed 15 December 2015.

- 1 2 Deutsch 1978, p. 560 [584].

- ↑ Youens 1997, pp. 100, 114.

- ↑ William Shakespear's / Schauspiele. / Neue Asugabe. / von / Joh. Joach. Eschenburg, / Professor am Collegio Carolino in Braunschweig. / Eilf'ter Band. / Zürich, bey Orell, Geßner, Füeßlin und Compagnie. / 1777, pp. 217–8 [221–2] (Title page of Vol. 11. NB Vol. 1 is dated 1775).

- ↑ C20 in Blinn & Schmidt 2003, p. 29, #830 in Hubbard 1880, p. 57. See also notes for #832 in Hubbard 1880, p. 58 = Blinn & Schmidt C80.

- ↑ Voß & Voß 1810, p. 173.

- 1 2 Drewing 1993, p. 89.

- ↑ Shakspeare's Othello und Konig Lear, ubersetzt von Dr. Johann Heinrich Voß, Professor am Weimarischen Gymnasium. Mit Compositionen von Zelter (Jena, 1806), cited in Drewing 1993, p. 82.

- ↑ Drewing 1993, p. 82.

- ↑ Drewing 1993, pp. 18, 245n.

- ↑ Blinn & Schmidt 2003, pp. 29–30.

- ↑ Drewing 1993, p. 17.

- ↑ This is C10 in Blinn & Schmidt 2003, p. 25.

- ↑ Drewing 1993, p. ii.

- 1 2 Drewing 1993, p. 90.

- ↑ (Blinn & Schmidt 2003), no. C130.

- ↑ Voß 1828, p. 44.

- ↑ Drewing 1993, p. 224.

- ↑ Drewing 1993, p. 220.

- ↑ Drewing 1993, p. 232.

- ↑ Drewing 1993, p. 63.

- ↑ Hubbard 1880, p. 58.

- ↑ Hubbard 1880, p. 58, no. 834 (2nd edition is no. 837); C200 in Blinn & Schmidt 2003, p. 32.

- ↑ Shakspeare's / Dramatische Werke, / übersetzt / von / A. W. Schlegel und J. J. Eschenburg. / Neunter Band. / Macbeth. / Cymbeline. Wien, bey Anton Pichler. 1811. (Title page p. 115, song, p. 159; C100 in Blinn & Schmidt 2003, p. 29.) A 2nd edition appeared in Leipzig in 1846, see de:Cymbeline.

- 1 2 Fischer-Dieskau 1976, p. 233.

- ↑ Schubert 1826, pp. 4–7.

- ↑ Search page of Hungarian National Library: search for

Ms. Mus. 4945 - ↑ 12 Lieder von Franz Schubert, S.558. ISMLP. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

Sources

- Blinn, Hansjürgen; Schmidt, Wolf Gerhard (2003). Shakespeare – deutsch: Bibliographie der Übersetzungen und Bearbeitungen (in German). Berlin: Erich Schmidt Verlag. ISBN 9783503061938.

- Brown, Maurice J. E. (1958). Schubert: a critical biography. London, New York: Macmillan / St. Martin's Press.

- Capell, Richard [1929]. Schubert's songs. New York: E. P. Dutton.

- Clive, Peter (2006). Brahms and His World: A Biographical Dictionary. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9781461722809.

- Dahms, Walter (1918). Schubert (in German). Berlin: Schuster & Loeffler.

- Deutsch, Otto (1978). Franz Schubert, thematisches Verzeichnis seiner Werke in chronologischer Folge (in German). Kassel: Bärenreiter. ISBN 9783761805718. NB rip-off scan, still in copyright...

- Drewing, Lesley M. (1993). Voß Shakespeare translation. An assessment to the contribution made by Johann Heinrich Voß and his sons to the theory and practice of Shakespeare translation in Germany (PDF) (D. Phil. dissertation) (in English and German). University of Durham. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- Eschenburg, J. J. (1805). William Shakspeare's Schauspiele / Neue, ganz umgearbeitete Ausgabe von Johann Joachim Eschenburg / Eilfter Band. 11. (contains Cymbelin, Titus Andronikus, König Lear). Zürich: Orell, Füßli & Co.

- Feurzeig, Lisa (2014). Schubert's Lieder and the Philosophy of Early German Romanticism. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 9781472401298.

- Fischer-Dieskau, Dietrich (1976). Schubert: a biographical study of his songs. London: Cassell.

- Furness, Howard Horace, ed. (1913). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Tragedie of Cymbeline. Philadelphia and London (John Street, Adelphi): J. B. Lippincott.

- Grove, George (1951). Beethoven – Schubert – Mendelssohn. London: Macmillan & Co.

- Hanmer, Thomas (1744). The works of Shakespear in 9 volumes. With a glossary. Carefully printed from the Oxford edition in quarto, 1744. Nil ortum tale. Hor. London: J. and P. Knapton et mult. al. (For Horace, see Stone 2005, p. 286)

- Hubbard, James Mascarene (1880). Catalogue of the works of William Shakespeare / original and translated / together with the Shakespeariana embraced in the Barton Collection of the Boston Public Library. Boston: Printed by order of the Trustees.

- Johnson, Graham (1996). "Ständchen 'Horch, horch! die Lerch', D889". Hyperion Records. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- Johnson, Graham (1996). "An Silvia 'Gesang an Silvia', D891". Hyperion Records. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- Keßler, Georg Wilhelm (trans.) (1809). Shakespeare's Cymbeline. Berlin: Julius Eduard Hißig. was reprinted in (C90. Mehrer Verfassen)

- Kreissle von Hellborn, Heinrich (1869). Coleridge, Arthur D.; Grove, George, eds. The Life of Franz Schubert (in 2 volumes). London: Longman, Green and Co. Volume 1 Volume 2

- Pope, Alexander (1723). The Works of Mr. William Shakespear / Volume the Sixth / consisting of / Tragedies from Fable. The works of Shakespear in six volumes.

- Pope, Alexander; Warburton, William (1747). The Works of Shakespear: Volume the Seventh. Containing, Julius Caesar. Antony and Cleopatra. Cymbeline. Troilus and Cressida. Dublin: Printed for R. Owen, J. Leathley, G. and A. Ewing, W. and J. Smith, G.Faulkner, P. Crampton, A. Bradley, T. Moore, E. and J. Exshaw.

- Reed, John (1997). The Schubert Song Companion. Manchester University Press,. ISBN 9781901341003.

- Tieck, Dorothea; Baudissin, Wolf, eds. (1833). William Shakespeares dramatische Werke / Uebersetz von A. W. Schlegel, ergänzt und erläutert von Ludwig Tieck. 9. Translated by Schlegel, A. W. Berlin: G. Reimer.

- Schubert, Franz (July 1826). "Sammelmanuskript [fing. Titel]" (in German). [contains MS of Trinklied, Ständchen, Hyppolits Lied and Gesang ('Was ist Silvia?'), D888-891]. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- Schubert, Franz (26 October 1830). Franz Schubert's nachgelassene musikalische Dichtungen für Gesang und Pianoforte (in German). (Plate no. 3704). Vienna: Ant.[on] Diabelli & Comp.[agnie]. The actual page:

- Schubert, Franz (1832). Diabelli, Anton, ed. Ständchen von Shakespeare. (Horch, horch, die Lerch‘ im Aetherblau) / in Musik gesetzt von Franz Schubert. Philomele : eine Sammlung der beliebtesten Gesänge mit Begleitung des Pianoforte / eingerichtet und hrsg. von Anton Diabelli ; No. 294 (in German). Plate number D. et C. No 4059. Vienna: Diabelli et Comp. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- Stone, Jon R. (2005). Routledge Dictionary of Latin Quotations: The Illiterati's guide to Latin Maxims, Mottoes, Proverbs, and Sayings. New York, London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-96909-3.

- Woodford, Peggy (2010). Schubert: Illustrated Lives Of The Great Composers. Omnibus Press. ISBN 9780857124951.

- Vincent, Charles, ed. (1916). Fifty Shakespere songs for high voice. Boston: Oliver Ditson Company.

- Voß, Abraham (1828). Shakespeare's Schauspiele / von Johann Heinrich Voß / und dessen Söhne / Heinrich Voß und Abraham Voß /mit Erläuterungen/ Achtes Bandes erste Abtheilung. (also contains Hamlet by J. H Voß, and Die lustige Weiber von Windsor by Heinrich Voß). Stuttgart: J. B. Metzler'chen Buchhandlung.

- Voß, Heinrich; Voß, Abraham (trans.) (1810). Schauspiele von William Shakespeare: Erster Band [Macbeth & Cymbeline] (in German). Tübingen: J. G. Cotta'schen Buchhandlung. Title page, p. 125

- Youens, Susan (1997). "Schubert and his poets: issues and conundrums". In Gibbs, Christopher H. The Cambridge Companion to Schubert. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521484244.