Screen Actors Guild

| |

| Founded | July 12, 1933 |

|---|---|

| Date dissolved | March 30, 2012 |

| Merged into | SAG-AFTRA |

| Members |

129,092 ("active" members) 54,690 (other members; withdrawn/suspended) (before merger, 2012)[1] |

| Affiliation | AAAA (AFL-CIO), FIA |

| Key people |

|

| Office location | Hollywood, California |

| Country | United States |

| Website |

www |

The Screen Actors Guild (SAG) was an American labor union which represented over 100,000 film and television principal and background performers worldwide. On March 30, 2012, the union leadership announced that the SAG membership voted to merge with the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (AFTRA) to create SAG-AFTRA.[2]

According to SAG's Mission Statement, the Guild sought to: negotiate and enforce collective bargaining agreements that establish equitable levels of compensation, benefits, and working conditions for its performers; collect compensation for exploitation of recorded performances by its members, and provide protection against unauthorized use of those performances; and preserve and expand work opportunities for its members.[3]

The Guild was founded in 1933 in an effort to eliminate exploitation of actors in Hollywood who were being forced into oppressive multi-year contracts with the major movie studios that did not include restrictions on work hours or minimum rest periods, and often had clauses that automatically renewed at the studios' discretion. These contracts were notorious for allowing the studios to dictate the public and private lives of the performers who signed them, and most did not have provisions to allow the performer to end the deal.[4]

The Screen Actors Guild was associated with the Associated Actors and Artistes of America (AAAA), which is the primary association of performer's unions in the United States. AAAA is affiliated with the AFL–CIO. SAG claimed exclusive jurisdiction over motion picture performances, and shared jurisdiction of radio, television, Internet, and other new media with its sister union AFTRA, with which it shared 44,000 dual members.[5] Internationally, the SAG was affiliated with the International Federation of Actors.

In addition to its main offices in Hollywood, SAG also maintained local branches in several major US cities, including Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, Dallas, Denver, Detroit, Honolulu, Houston, Las Vegas, Miami, Nashville, New York City, New Orleans, Philadelphia, Phoenix, Portland, Salt Lake City, San Diego, San Francisco, Seattle, and Washington, D.C.

Since 1995, the guild annually awarded the Screen Actors Guild Awards, which are considered an indicator of success at the Academy Awards. This award is continued by SAG-AFTRA.

History

Early years

In 1925, the Masquers Club was formed by actors discontent with the grueling work hours at the Hollywood studios.[6] This was one of the major concerns which led to the creation of the Screen Actors Guild in 1933. Another was that the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, which at that time arbitrated between the producers and actors on contract disputes, had a membership policy which was by invitation only.

A meeting in March 1933 of six actors (Berton Churchill, Charles Miller, Grant Mitchell, Ralph Morgan, Alden Gay, and Kenneth Thomson) led to the guild's foundation. Three months later, three of the six and eighteen others became the guild's first officers and board of directors: Ralph Morgan (its first president), Alden Gay, Kenneth Thomson, Alan Mowbray (who personally funded the organization when it was first founded), Leon Ames, Tyler Brooke, Clay Clement, James Gleason, Lucile Webster Gleason, Boris Karloff, Claude King, Noel Madison, Reginald Mason, Bradley Page, Willard Robertson, Ivan Simpson, C. Aubrey Smith, Charles Starrett, Richard Tucker, Arthur Vinton, Morgan Wallace and Lyle Talbot.

Many high-profile actors refused to join SAG initially. This changed when the producers made an agreement amongst themselves not to bid competitively for talent. A pivotal meeting, at the home of Frank Morgan (Ralph's brother, who played the title role in The Wizard of Oz), was what gave SAG its critical mass. Prompted by Eddie Cantor's insistence, at that meeting, that any response to that producer's agreement help all actors, not just the already established ones, it took only three weeks for SAG membership to go from around 80 members to more than 4,000. Cantor's participation was critical, particularly because of his friendship with the recently elected President Franklin D. Roosevelt. After several years and the passage of the National Labor Relations Act, the producers agreed to negotiate with SAG in 1937.

Actors known for their early support of SAG (besides the founders) include Edward Arnold, Humphrey Bogart, James Cagney, Dudley Digges, Porter Hall, Paul Harvey, Jean Hersholt, Russell Hicks, Murray Kinnell, Gene Lockhart, Bela Lugosi, David Manners, Fredric March, Adolphe Menjou, Chester Morris, Jean Muir, George Murphy, Erin O'Brien-Moore, Irving Pichel, Dick Powell, Edward G. Robinson, Edwin Stanley, Gloria Stuart, Lyle Talbot, Franchot Tone, Warren William, and Robert Young.

Blacklist years

In October 1947, the members of a list of suspected communists working in the Hollywood film industry were summoned to appear before the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), which was investigating Communist influence in the Hollywood labor unions. Ten of those summoned, dubbed the "Hollywood Ten", refused to cooperate and were charged with contempt of Congress and sentenced to prison. Several liberal members of SAG, led by Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Danny Kaye, and Gene Kelly formed the Committee for the First Amendment (CFA) and flew to Washington, DC, in late October 1947 to show support for the Hollywood Ten. (Several of the CFA's members, including Bogart, Edward G. Robinson, and John Garfield later recanted, saying they had been "duped", not realizing that some of the Ten were really communists.)

The president of SAG – future United States President Ronald Reagan – also known to the FBI as Confidential Informant "T-10", testified before the committee but never publicly named names. Instead, according to an FBI memorandum in 1947: "T-10 advised Special Agent [name deleted] that he has been made a member of a committee headed by Mayer, the purpose of which is allegedly is to 'purge' the motion-picture industry of Communist party members, which committee was an outgrowth of the Thomas committee hearings in Washington and subsequent meetings . . . He felt that lacking a definite stand on the part of the government, it would be very difficult for any committee of motion-picture people to conduct any type of cleansing of their own household".[7] Subsequently a climate of fear, enhanced by the threat of detention under the provisions of the McCarran Internal Security Act, permeated the film industry. On November 17, 1947, the Screen Actors Guild voted to force its officers to take a "non-communist" pledge. On November 25 (the day after the full House approved the ten citations for contempt) in what has become known as the Waldorf Statement, Eric Johnston, president of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), issued a press release: "We will not knowingly employ a Communist or a member of any party or group which advocates the overthrow of the government of the United States by force or by any illegal or unconstitutional methods."

None of those blacklisted were proven to advocate overthrowing the government – most simply had Marxist or socialist views. The Waldorf Statement marked the beginning of the Hollywood blacklist that saw hundreds of people prevented from working in the film industry. During the height of what is now referred to as McCarthyism, the Screen Writers Guild gave the studios the right to omit from the screen the name of any individual who had failed to clear his name before Congress. At a 1997 ceremony marking the 50th anniversary of the Blacklist, the Guild's president made this statement:

Only our sister union, Actors Equity Association, had the courage to stand behind its members and help them continue their creative lives in the theater. ... Unfortunately, there are no credits to restore, nor any other belated recognition that we can offer our members who were blacklisted. They could not work under assumed names or employ surrogates to front for them. An actor's work and his or her identity are inseparable. Screen Actors Guild's participation in tonight's event must stand as our testament to all those who suffered that, in the future, we will strongly support our members and work with them to assure their rights as defined and guaranteed by the Bill of Rights.

1970s to 2012

The Screen Actors Guild Ethnic Minorities Committee was co-founded in 1972 by actors Henry Darrow, Edith Diaz, Ricardo Montalban and Carmen Zapata.[9]

The Screen Actors Guild Women's Committee was founded in 1972.

Marquez v. Screen Actors Guild

In 1998, Naomi Marquez filed suit against SAG and Lakeside Productions claiming they had breached their duty of fair representation. The claim was denied by the Supreme Court.

Merger with AFTRA

The membership of the Screen Actors Guild voted to merge with the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists on March 30, 2012.[2]

Composition

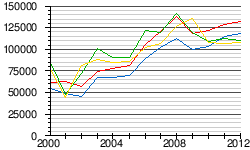

According to SAG's Department of Labor records since 2006, when membership classifications were first reported, 30%, or almost a third, of the guild's total membership had consistently been considered "withdrawn," "suspended," or otherwise not categorized as "active" members. These members were ineligible to vote in the guild.[10] "Honorable withdrawals" constituted the largest portion of these, at 20% of the total membership, or 36,284 members before the merger in 2012. "Suspended" members were the second largest, at 10%, or 18,402 members.[1] This classification scheme is continued by SAG-AFTRA.[11]

Rules and procedure

Becoming a member

An actor was eligible to join the Screen Actors Guild by meeting the criteria in any of the following three categories: principal actor in a SAG production, background actor (originally the "three voucher rule"), and one-year member of an affiliated union (with a principal role). The basic categories were:

- Principal actor: Any actor who works as a principal actor for a minimum of one day on a project (film, commercial, TV show, etc.) under a producer's agreement with SAG, and the actor has been paid at the appropriate SAG daily, three-day, or weekly rate was then considered "SAG-eligible". A SAG-eligible actor could work in other SAG or non-SAG productions up to 30 days, during which that actor was classified as a "Taft-Hartley". After the 30-day Taft-Hartley period has expired, the actor could not work on any further SAG productions until first joining SAG, by: paying the initiation fee with the first half-year minimum membership dues, and agreeing to abide by the Guild's rules and bylaws.

- Background actor: For years, SAG had the "three voucher rule". After collecting three valid union vouchers for three separate days of work, a background actor could become SAG-eligible; however, employment must have been confirmed with payroll data, not vouchers. SAG productions required a minimum number of SAG members be employed as background actors before a producer was permitted to hire a non-union background actor. For television productions in the West Coast Zones, the minimum number of SAG background actors was 21 (25 in the New York Zone), for commercials the minimum was 40, and for feature films, the minimum was 57 in the West Coast zones (85 in the New York zone). In rare circumstances, due to the uniqueness of a role, or constraints on the numbers of available SAG actors or last-minute cancellations, those minimums were unable to be met. When this happened, producers were permitted to fill one or more of those union spots with non-union actors. The non-union actor chosen to fill the union spot was then issued a union background voucher for the day, and that non-union actor was entitled to all the same benefits and pay that the union actor would have received under that voucher. This was called a Taft-Hartley voucher. The SAG-Eligible background actor could continue working in non-union productions, but after obtaining 3 Taft-Hartley vouchers were given a 30-day window where they were allowed to work as many SAG jobs as they wish. After the 30-day window had expired the actor became a "Must Join" with SAG, meaning they could no longer work any SAG projects without formally joining the union. They could continue to work non-union jobs, however, until they officially became a SAG member.[12]

- Member of an affiliated union: Members in good standing, for at least one year, of any of the other unions affiliated with the AAAA, and who had worked as a principal at least once in an area of the affiliated union's jurisdiction, and who had been paid for their work in that principal role, were eligible to join SAG.

Initiation fee and membership dues

Members joining the Los Angeles, New York, or Miami SAG locals were assessed an initial fee to join the Guild of $3,000. At the time of initiation, the first minimum semi-annual membership dues payment of $58 must have also been paid, bringing the total amount due upon initiation into the Guild to $3,058.[13] All other SAG locals still assessed initiation fees at the previous rate. Members from other locales who worked in Los Angeles, New York, or Miami after joining were charged the difference between the fee they paid their local and the higher rate in those markets.

Membership dues were calculated and due semi-annually, and were based upon the member's earnings from SAG productions. The minimum annual dues amount was $116, with an additional 1.85% of the performer's income up to $200,000. Income from $200,000 to $500,000 was assessed at 0.5%, and income from $500,000 to $1 million was assessed at 0.25%. For the calculation of dues, there was a total earnings cap at $1 million. Therefore, the maximum dues payable in any one calendar year by any single member was limited to $6,566.

SAG members who became delinquent in their dues without formally requesting a leave of absence from the Guild were assessed late penalties, and risked being ejected from the Guild and could be forced to pay the initiation fee again to regain their membership.

Global Rule One

The SAG Constitution and Bylaws stated that, "No member shall work as a performer or make an agreement to work as a performer for any producer who has not executed a basic minimum agreement with the Guild which is in full force and effect."[14] Every SAG performer agreed to abide by this, and all the other SAG rules, as a condition of membership into the Guild. This means that no SAG members could perform in non-union projects that were within SAG's jurisdiction, once they became members of the Guild. Since 2002, the Guild had pursued a policy of world-wide enforcement of Rule One, and renamed it Global Rule One.

However, many actors, particularly those who do voices for anime dubs, have worked for non-union productions under pseudonyms. For example, David Cross did voices for the non-union cartoon Aqua Teen Hunger Force, under the pseudonym "Sir Willups Brightslymoore." He acknowledged that work in an interview with SuicideGirls.[15] Such violations of Global Rule One had generally gone ignored by the Guild.

Unique stage names

Like other guilds and associations that represent actors, SAG rules stipulated that no two members may have identical working names. Some actors have added their middle initial. Notable examples include Michael Keaton, Michael J. Fox and Emma Stone, whose birth names "Michael Douglas", "Michael Fox" and "Emily Stone," respectively, were already in use.

Member benefits and privileges

SAG contracts with producers contained a variety of protections for Guild performers. Among these provisions were: minimum rates of pay, adequate working conditions, special protection and education requirements for minors, arbitration of disputes and grievances, and affirmative action in auditions and hiring.

Standardized pay and work conditions

All members of the Guild agreed to work only for producers who had signed contracts with SAG. These contracts spelled out in detail the responsibilities that producers must assume when hiring SAG performers. Specifically, the SAG basic contract specified: the number of hours performers may work, the frequency of meal breaks required, the minimum wages or "scale" at which performers must be compensated for their work, overtime pay, travel accommodations, wardrobe allowances, stunt pay, private dressing rooms, and adequate rest periods between performances. When applicable, and with due regard to the safety of the individuals, cast and crew, women and minorities were to be considered for doubling roles and for descript and non-descript stunts on a functional, non-discriminatory basis.

The Producers and the Pension and Health Plans

Performers who meet the eligibility criteria of working a certain number of days or attaining a certain threshold in income derived from SAG productions could join the Producers Pension and Health Plans offered by the Guild. The eligibility requirements varied by age of the performer and the desired plan chosen (there were two health plans). There were also Dental, Vision, and Life & Disability coverage included as part of the two plans.[16]

Residuals

The Guild secured residuals payments in perpetuity to its members for broadcast and re-broadcast of films, TV shows, and TV commercials through clauses in the basic SAG agreements with producers.

Major strikes and boycotts

Early strikes

In July 1948, a strike was averted at the last minute as the SAG and major producers agreed upon a new collective bargaining contract. The major points agreed upon included: full union shop for actors to continue, negotiations for films sent direct to TV, producers could not sue an actor for breach of contract if they strike (but the guild could only strike when the contract expires).[17]

In March 1960, SAG went on strike against the seven major studios. This was the first industry-wide strike in the 50-year history of movie making. Earlier walkouts involved production for television. The Writers Guild of America had been on strike since January 31, 1960 with similar demands to the actors. The independents were not affected since they signed new contracts. The dispute rested on actors wanting to be paid 6% or 7% of the gross earnings of pictures made since 1948 and sold to television. Actors also wanted a pension and welfare fund.[18]

In December 1978, members of SAG went on strike for the fourth time in its 45-year history. It joined the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists in picket lines in Los Angeles and New York. The unions said that management's demand would cut actors' salaries. The argument was over filming commercials. Management agreed to up salaries from $218 to $250 per scene, but if the scene were not used at all, the actor would not be paid.[19]

Strike and Emmy Awards boycott of 1980

In July, SAG members walked out on strike, along with AFTRA, the union for television and radio artists, and the American Federation of Musicians. The union joined the television artists in calling for a successful boycott against that year's prime-time Emmy awards. Powers Boothe was the only one of the 52 nominated actors to attend: "This is either the most courageous moment of my career or the stupidest" he quipped during his acceptance speech. The guild ratified a new pact, for a 32.25% increase in minimum salaries and a 4.5% share of movies made for pay TV, and the strike ended on October 25.[20]

The commercials strike of 2000

The commercials strike of 2000 was extremely controversial. Some factions within SAG call it a success, asserting that it not only saved Pay-Per-Play (residuals) but it also increased cable residuals by 140% up from $1,014 to $2,460. Others suggested almost identical terms were available in negotiation without a strike. In the wake of the strike, SAG, and its sister union AFTRA, gathered evidence on over 1,500 non-members who had worked during the strike. SAG trial boards found Elizabeth Hurley and Tiger Woods guilty of performing in non-union commercials and both were fined $100,000 each.

Beyond the major studios

SAG Principal members could not work on non-union productions. Union background actors were not fully covered nationwide and could work non-union outside the background zones. These background zones included the state of Hawai'i, 4 zones in California, Las Vegas NV, and a 300-mile radius around New York City. Many film schools had SAG Student Film Agreements with the Guild to allow SAG actors to work in their projects. SAGIndie was formed in 1997 to promote using SAG actors; SAG also had Low Budget Contracts that were meant to encourage the use of SAG members on films produced outside of the major studios and to prevent film productions from leaving the country, known as "Runaway production". In the fight against "Runaway production", the SAG National Board voted unanimously to support the Film and Television Action Committee (FTAC) and its 301(a) Petition which asked the US Trade Representative to investigate Canadian film subsidies for their violation of trade agreements Canada signed with the United States.

Financial core

Financial core, or Fi-Core, was a payment to a union to allow someone to work in a union environment without being a member of the union. The concept was defined in 1963 by Supreme Court case Labor Board v. General Motors[21] and clarified for the communications industry in 1988 via Communications Workers of America v. Beck.

Approximately 96% of normal union dues must have been paid to be a Financial Core member of the SAG,[21][22][23] and Financial Core members may not "represent themselves as Screen Actors Guild members."[24] Additionally, the Screen Actors Guild said "Fi-Core/FPNM are viewed as scabs ... by SAG members, directors, and writers—most of whom also belong to entertainment unions".[24] This statement had been met with skepticism by some.[21][23][25]

Former SAG President Charlton Heston was apparently a supporter of Fi-Core.[25][26][27][28]

National Women's Committee

Entertainment remains among the most gender unequal industries in the United States. The National Women's Committee operated within the National Statement of Purpose to promote equal employment opportunities for its female SAG members. It also encouraged positive images of women in film and television, in order to end sexual stereotypes and educate the industry about the representation of women, both in numbers and quality of representation.[29]

SAG Women's Committee had been dedicated to working towards strategic objectives adopted from the Fourth World Conference on Women Beijing Platform of 1995. These objectives included supporting research into all aspects of women and the media so as to define areas needing attention and action. The SAG Hollywood Division Women's Committee also encouraged the media to refrain from presenting women as inferior beings and exploiting them as sexual objects and commodities.[29]

Woman's Committee timeline

- 1972: The Screen Actors Guild Women's Committee is founded. Brigham Young University conducts a study that reveals 81.7% of television roles are male, versus 18.3% female.

- 1974–1976: In conjunction with the Directors Guild of America, the Screen Actors Guild compiles statistical surveys that explicitly document the disenfranchisement of their women members, often linking the data to a specific studio, network and in several cases individual television shows. These efforts are spearheaded by the two organizations' individual Women's Committees.

- 1975: Kathleen Nolan becomes the Screen Actors Guild's first female president.[30]

- 1979: A study reveals that between 1949 and 1979, 7,332 feature films were made and released by major distributors. Fourteen, a mere 0.19%, were directed by women.

- October 10, 1979: Women and Minorities Rally. President Kathleen Nolan leads protest rally, with signs reading "Women and Minorities: Not Seen on the American Scene"..."Window Dressing on the Set"...and "TV: it's Time for a Facelift".[30]

- 1981–1985: Leslie Hoffman, first stuntwoman elected to the Hollywood Screen Actors Board. She works towards hiring more women, minorities, seniors, and disabled performers as stuntpeople. She is blacklisted by the Screen Actors Guild Board and Stuntmen Groups.

- 1984: SAG creates additional low-budget motion picture agreement, giving advantages to productions that hire more women, minorities, seniors, and disabled performers. SAG's New York branch forms Women's Voice-Over Committee to study why women get only 10–20% of voiceover work.[30]

- 1986: Women's voice-over study by McCollum/Spielman and Company indicates "it makes absolutely no difference whether a male or female voice is used as a TV commercial voice-over", destroying long-held advertising industry assertion that male voices "sell better" and carry "more authority".[30]

- 1989: A SAG report reveals that 71% of all roles in feature films and 64% of all roles in TV went to men. The report said the combined income of men more than doubled that of women ($644 million to $296 million).

- 1990: At the SAG National Women's Conference, Meryl Streep keynotes first national event, emphasizing the decline in women's work opportunities, pay parity, and role models within the film industry.[30] She lashes out at the film industry for downplaying the importance of women both on screen and off.

- 1996: Composition of female leading roles rises to 40%, but supporting roles for women decline to 33%.

- 1997: SAG contracts for actresses exceed $472 million, while male SAG contracts receive more than $928 million.

- 2004: Only 37% of all SAG television and film roles go to women.[31]

- 2008: Kathryn Bigelow becomes the first woman to win the Oscar for Best Director of a Motion Picture, after being only the fourth woman in history to secure a nomination. Statistics show that only 9% of directors are female.[32]

- 2009: Dr. Martha Lauzen of the Alliance for Women Film Journalists, conducts a study revealing that, of 2009's top 250 films at box offices, women comprised only 16% of the directors, producers, writers, and other top jobs. This represents a 3% decline from the 2001 study showing 19% female composition.[33] Female directors fall from a low 9% in 2008, to a meager 7%. Warner Brothers Pictures and Paramount Pictures did not release a single film directed by a woman.[34]

- 2010: A study carried out by the Annenberg School for Communication and the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in the Media finds that male characters outnumber female characters by 2.42 to one in top-grossing American films.

- 2010: Ex-Board Member Leslie Hoffman successfully fights to get Disability Health Plans for two stuntmen and a reimbursement for a disabled stuntwoman.

Presidents

- 1933–1933 Ralph Morgan

- 1933–1935 Eddie Cantor

- 1935–1938 Robert Montgomery

- 1938–1940 Ralph Morgan

- 1940–1942 Edward Arnold

- 1942–1944 James Cagney

- 1944–1946 George Murphy

- 1946–1947 Robert Montgomery

- 1947–1952 Ronald Reagan

- 1952–1957 Walter Pidgeon

- 1957–1958 Leon Ames

- 1958–1959 Howard Keel

- 1959–1960 Ronald Reagan

- 1960–1963 George Chandler

- 1963–1965 Dana Andrews

- 1965–1971 Charlton Heston

- 1971–1973 John Gavin

- 1973–1975 Dennis Weaver

- 1975–1979 Kathleen Nolan

- 1979–1981 William Schallert

- 1981–1985 Edward Asner

- 1985–1988 Patty Duke

- 1988–1995 Barry Gordon

- 1995–1999 Richard Masur

- 1999–2001 William Daniels

- 2001–2005 Melissa Gilbert

- 2005–2009 Alan Rosenberg

- 2009–2012 Ken Howard (president of SAG-AFTRA, 2012–2016)

- 2016 Gabrielle Carteris, appointed acting President after Ken Howard's death on March 23, 2016

See also

- Actors' Equity Association (AEA)

- ACTRA

- American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (AFTRA)

- Asociación Nacional de Actores (ANDA)

- British Actors' Equity Association

- SAG Foundation

- Screen Actors Guild Awards

- The Screen Guild Theater

Notes

- 1 2 US Department of Labor, Office of Labor-Management Standards. File number 000-113. Report submitted April 20, 2012.

- 1 2 "SAG, AFTRA Members Approve Merger to Form SAG-AFTRA" (Press release). SAG-AFTRA. 30 March 2012. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- ↑ "Mission Statement". SAG Official Website.

- ↑ London Academy of Media, Film & TV, The Screen Actors Guild

- ↑ "Pause after Screen Actors Guild contract expires".

- ↑ "The Masquers Club official site".

- ↑ HERBERT MITGANG. Dangerous Dossiers: exposing the secret war against america's greatest authors. New York City, NY: Donald I. Fine, Inc, pp 31-33

- ↑ Krizman, Greg. "Hollywood Remembers the Blacklist", Screen Actor, January 1998 (special edition)

- ↑ "Actress Edith Diaz dies at 70; Credits include 'Sister Act' films and CBS' 'Popi' sitcom". Hollywood Reporter. 2010-02-08.

- 1 2 3 US Department of Labor, Office of Labor-Management Standards. File number 000-113. (Search)

- ↑ US Department of Labor, Office of Labor-Management Standards. File number 000-391. (Search)

- ↑ Handel, Jonathan. "SAG-AFTRA Merger Means Tougher Admissions, Potentially Costlier Membership". Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- ↑ Archived October 16, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Global Rule One | Screen Actors Guild". Retrieved 2016-08-10.

- ↑ Suicidegirls.com, web: SG-DCross.

- ↑ Health BenefitTabs-Eligibility

- ↑ Actors' Strike Threat Fades; Points Agreed. (July 8, 1948). Los Angeles Times, p. A1. Retrieved June 24, 2008

- ↑ ACTORS START STRIKE AT 7 MAJOR STUDIOS: Guild Turns Down Proposal to Finish Work on 8 Movies. (March 7, 1960). Los Angeles Times, p. 1. Retrieved June 24, 2008

- ↑ HARRY BERNSTEIN (December 20, 1978). Actors in Radio, TV Commercials Strike :Unions Say Ad Agencies Seek More Work for Less Money. Los Angeles Times, p. oc_a12. Retrieved June 24, 2008

- ↑ Facts on File 1980 Yearbook, p805

- 1 2 3 "FiCore Information". Fi-Core.com. Retrieved November 26, 2012.

- ↑ "Fi-Core FAQ by Bizparentz.com". Retrieved November 26, 2012.

- 1 2 "Gary Graham's on Fi-Core". Retrieved November 26, 2012.

- 1 2 "Get The Facts About Financial Core". Retrieved June 26, 2014.

- 1 2 "Lani Minella on Fi-Core". Retrieved November 26, 2012.

- ↑ "Dave Courvoisier on Fi-Core". Retrieved November 26, 2012.

- ↑ "Fi-Core.com - Resources". Retrieved November 26, 2012.

- ↑ "Mark Pirro on Fi-Core". Retrieved November 26, 2012.

- 1 2 "Women's Committee". Archived from the original on 25 January 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "SAG History - SAG Timeline". Archived from the original on May 14, 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ↑ "Professional Women: Vital Statistics" (PDF). Department for Professional Employees, AFL-CIO. April 2010. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- ↑ Taylor, Ella (October 21, 2009). "The New Generation of Female Filmmakers". Elle Magazine. Retrieved April 20, 2011.

- ↑ Merin, Jennifer. "Women on Film - Dr. Martha Lauzen's 2009 Celluloid Ceiling Report". Alliance of Women Film Journalists. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ↑ Dargis, Manhola (December 10, 2009). "Women in the Seats but Not Behind the Camera". The New York Times. Retrieved April 20, 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Screen Actors Guild. |

- Official website

- SAGIndie, the Independent Producers Outreach Program of the Screen Actors Guild

- "Hollywood Is a Union Town", The Nation (April 2, 1938)