String Quartet No. 12 (Dvořák)

The String Quartet in F major Op. 96, nicknamed American Quartet, is the 12th string quartet composed by Antonín Dvořák. It was written in 1893, during Dvořák's time in the United States. The quartet is one of the most popular in the chamber music repertoire.

Composition

|

Performance of the quartet by the Seraphina quartet (Caeli Smith and Sabrina Tabby, violins; Madeline Smith, viola; Genevieve Tabby, cello)

I. Allegro ma non troppo

II. Lento

III. Molto vivace

IV. Finale: vivace ma non troppo

|

| Problems playing these files? See media help. | |

Dvořák composed the quartet in 1893 during a summer vacation from his position as director (1892–1895) of the National Conservatory in New York City. He spent his vacation in the town of Spillville, Iowa, which was home to a Czech immigrant community. Dvořák had come to Spillville through Josef Jan Kovařík who had finished violin studies at the Prague Conservatory and was about to return to Spillville, his home in the United States, when Dvořák offered him a position as secretary, which Josef Jan accepted, so he came to live with the Dvořák family in New York.[1] He told Dvořák about Spillville, where his father Jan Josef was a schoolmaster, which led to Dvořák deciding to spend the summer of 1893 there.[2]

In that environment, and surrounded by beautiful nature, Dvořák felt very much at ease.[3] Writing to a friend he described his state of mind, away from hectic New York: "I have been on vacation since 3 June here in the Czech village of Spillville and I won’t be returning to New York until the latter half of September. The children arrived safely from Europe and we’re all happy together. We like it very much here and, thank God, I am working hard and I’m healthy and in good spirits."[4] He composed the quartet shortly after the New World Symphony, before that work had been performed.[5]

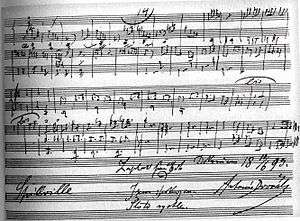

Dvořák sketched the quartet in three days and completed it in thirteen more days, finishing the score with the comment "Thank God! I am content. It was fast."[3] It was his second attempt to write a quartet in F major: his first effort, 12 years earlier, produced only one movement.[6] The American Quartet proved a turning point in Dvořák's chamber music output: for decades he had toiled unsuccessfully to find a balance between his overflowing melodic invention and a clear structure. In the American Quartet it finally came together.[3] Dvořák defended the apparent simplicity of the piece: "When I wrote this quartet in the Czech community of Spillville in 1893, I wanted to write something for once that was very melodious and straightforward, and dear Papa Haydn kept appearing before my eyes, and that is why it all turned out so simply. And it’s good that it did."[7]

For his symphony Dvořák gave the subtitle himself: "From the New World". To the quartet he gave no subtitle himself, but there is the comment "The second composition written in America."[8]

Negro, American or other influences?

For the London premiere of his New World symphony, Dvořák wrote: "As to my opinion I think that the influence of this country (it means the folk songs as are Negro, Indian, Irish etc.) is to be seen, and that this and all other works (written in America) differ very much from my other works as well as in couleur as in character,..."[9][10]

Dvořák's appreciation of African-American music is documented: Harry T. Burleigh, a baritone and later a composer, who knew Dvořák while a student at the National Conservatory, said, "I sang our Negro songs for him very often, and before he wrote his own themes, he filled himself with the spirit of the old Spirituals."[11] Dvořák said: "In the Negro melodies of America I discover all that is needed for a great and noble school of music."[12] For its presumed association with African-American music, the quartet was referred to with nicknames such as Negro and Nigger, before being called the American Quartet.[13][14] The older nicknames, without negative connotations for the composition, were abandoned after the 1950s.[15][16][17]

Dvořák wrote (in a letter he sent from America shortly after composing the quartet): "As for my new Symphony, the F major String Quartet and the Quintet (composed here in Spillville) – I should never have written these works 'just so' if I hadn't seen America."[18] Listeners have tried to identify specific American motifs in the quartet. Some have claimed that the theme of the second movement is based on a Negro spiritual, or perhaps on a Kickapoo Indian tune, which Dvořák heard during his sojourn at Spillville.[19]

A characteristic, unifying element throughout the quartet is the use of the pentatonic scale. This scale gives the whole quartet its open, simple character, a character that is frequently identified with American folk music. However, the pentatonic scale is common in many ethnic musics worldwide, and Dvořák had composed pentatonic music, being familiar with such Slavonic folk music examples, before coming to America.[20]

On the whole, specific American influences are doubted: "In fact the only American thing about the work is that it was written there," writes Paul Griffiths.[21] "The specific American qualities of the so-called "American" Quartet are not easily identifiable, writes Lucy Miller, "...Better to look upon the subtitle as simply one assigned because of its composition during Dvořák's American tour."[22]

Some have heard suggestions of a locomotive in the last movement, recalling Dvořák's love of railroads.[23]

The one confirmed musical reference in the quartet is to the song of the scarlet tanager, an American songbird. Dvořák was annoyed by this bird's insistent chattering, and transcribed its song in his notebook. The song appears as a high, interrupting strain in the first violin part in the third movement.[24]

Structure

The quartet is scored for the usual complement of two violins, viola, and cello, and comprises four movements:[25] A typical performance lasts around 30 minutes.

I. Allegro ma non troppo

The opening theme of the quartet is purely pentatonic, played by the viola, with a rippling F major chord in the accompanying instruments. This same F major chord continues without harmonic change throughout the first 12 measures of the piece. The movement then goes into a bridge, developing harmonically, but still with the open, triadic sense of openness and simplicity.

The second theme, in A major, is also primarily pentatonic, but ornamented with melismatic elements reminiscent of Gypsy or Czech music. The movement moves to a development section that is much denser harmonically and much more dramatic in tempo and color.

The development ends with a fugato section that leads into the recapitulation.

After the first theme is restated in the recapitulation, there is a cello solo that bridges to the second theme.

II. Lento

The theme of the second movement is the one that interpreters have most tried to associate with a Negro spiritual or with an American Indian tune. The simple melody, with the pulsing accompaniment in second violin and viola, does indeed recall spirituals or Indian ritual music. It is written using the same pentatonic scale as the first movement, but in the minor (D minor) rather than the major. The theme is introduced in the first violin, and repeated in the cello. Dvořák develops this thematic material in an extended middle section, then repeats the theme in the cello with an even thinner accompaniment that is alternately bowed and pizzicato.

III. Molto vivace

The third movement is a variant of the traditional scherzo. It has the form ABABA: the A section is a sprightly, somewhat quirky tune, full of off-beats and cross-rhythms. The song of the scarlet tanager appears high in the first violin.

The B section is actually a variation of the main scherzo theme, played in minor, at half tempo, and more lyrical. In its first appearance it is a legato line, while in the second appearance the lyrical theme is played in triplets, giving it a more pulsing character.

IV. Finale: vivace ma non troppo

The final movement is in a traditional rondo form, ABACABA. Again, the main melody is pentatonic.

The B section is more lyrical, but continues in the spirit of the first theme.

The C section is a chorale theme.

Performance and influence

In a first "private" performance of the quartet, in Spillville, June 1893, Dvořák himself played first violin, Jan Josef Kovařík second violin, daughter Cecilie Kovaříková viola, and son Josef Jan Kovařík the cello.[8]

The first two public performances of the quartet were by the Kneisel quartet, in Boston on 1 January 1894,[26][27] and then In New York on 13 January. An unnamed reviewer wrote the next day that to be sure, "there is none of the soaring or the yearning of the mighty Beethoven", but that there is "the spirit of eternal sunshine" which is "the soul of Mozart's music".[28] Burghauser mentions press notices in both cities, the first in the New York Herald, 18 December 1893.[8]

While the influence of American folk song is not explicit in the quartet, the impact of Dvořák's quartet on later American compositions is clear. Following Dvořák, a number of American composers turned their hands to the string quartet genre, including John Knowles Paine, Horatio Parker, George Whitefield Chadwick, and Arthur Foote. "The extensive use of folk-songs in 20th century American music and the 'wide-open-spaces' atmosphere of 'Western' film scores may have at least some of their origins" in Dvořák's new American style, writes Butterworth.[29]

Notes

- ↑ Clapham 1979, Norton, pp. 112–113

- ↑ Clapham 1979, Norton, pp. 119–120

- 1 2 3 Milan Slavicky. "String quartet in F major Op. 96 'American'," sleeve notes to Dvořák: String Quartets (complete), Stamitz Quartet. Brilliant Classics No. 99949, 2002.

- ↑ Letter to Jindrich Geisler, quoted in string quartet no. 12 "american" at www

.antonin-dvorak .cz - ↑ Šourek. p. 20

- ↑ Šourek. p. 89

- ↑ Quoted in string quartet no. 12 "american" at www

.antonin-dvorak .cz - 1 2 3 Burghauser, Jarmil. Antonin Dvořák: Thematic Catalogue, with a bibliography and a Survey of Life and Work, Bãrenreiter Supraphon, Prague, 1996, p. 302

- ↑ Excerpts from Dvorak’s correspondence: to the secretary of London’s Philharmonic Society, Francesco Berger (Vysoka, 12. 6. 1894), quoted in symphony no. 9 "from the new world" at www

.antonin-dvorak .cz - ↑ Program notes written by Dvořák for the first London performance of the New World symphony, quoted in Neil Butterworth, Dvořák: his life and times (1980, Midas Books, ISBN 0-85936-142-X), p. 103

- ↑ Jean E. Snyder, `A great and noble school of music: Dvořák, Harry T. Burleigh, and the African American Spiritual.' In Tibbetts, John C., Ed., Dvořák in America: 1892–1895, Amadeus Press, Portland, Oregon 1993, p. 131

- ↑ Interviewed by James Creelman, New York Herald, May 21, 1893

- ↑ John Clapham. "Bedrich Smetana and Antonin Dvorak" in Chamber Music, edited by Alec Robertson. Penguin Books, 1963.

- ↑ Michael Kennedy and Joyce Bourne (eds.) "‘American’ Quartet" in The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Music. Oxford University Press, 1996. ISBN 0198608845 ISBN 9780198608844 (2004 reprint)

- ↑ Hughes, 1967, p. 165, wrote that the quartet is "commonly known as the 'Nigger' quartet (although since that word has become taboo in the country of its origin the nickname has fallen somewhat into disuse)"

- ↑ Liane Curtis (ed.) A Rebecca Clarke Reader, pp. 102, 104. The Rebecca Clarke Society, 2004. ISBN 0977007901 ISBN 9780977007905

- ↑ Norman Edwards. Questions of Music. 2005, p 39. ISBN 978 1 84728 090 9

- ↑ Letter to Emil Kozanek, September 15, 1893, translated in Letters of Composers, Gertrude Norman and Miriam Lubell Shrifte, editors (1946, Alfred A Knopf, Inc.)

- ↑ Butterworth, p. 107

- ↑ John H. Baron. Intimate Music: A History of the Idea of Chamber Music, p. 363. Pendragon Press, 1998. ISBN 1576471004 ISBN 9781576471005

- ↑ Paul Griffiths, The String Quartet, A History(1983, Thames and Hudson ISBN 0-500-27383-9)

- ↑ Lucy Miller, Adams to Zemlinsky (2006, Concert Artists Guild, ISBN 1-892862-09-3), p. 123.

- ↑ Butterworth, p. 89

- ↑ Miller, p. 124

- ↑ This analysis is based on analyses in Griffiths, Miller, and "Antonin Dvořák" in Walter Willson Cobbett, Cobbett's Cyclopedic Survey of Chamber Music(1923, Oxford University Press)

- ↑ Hughes, p. 172

- ↑ Butterworth, p. 110

- ↑ The New York Times 14 January 1894, p. 11.

- ↑ Butterworth, p. 95

Sources

- Clapham, John (1979), Dvořák, New York: W. W. Norton, ISBN 0-393-01204-2

- Dvořák, Antonín: Quartetto XII. Fa maggiore. Score. Prague: Editio Supraphon, 1991. S 1304

- Hughes, Gervase, Dvořák: His Life & Music, 1967, Dodd, Mead, New York

- Šourek, Otakar; (Trans.)Samsour, Roberta Finlayson. The Chamber Music of Antonín Dvořák (PDF). Czechoslovakia: Artia.

External links

- String Quartet No.12, Op.96: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- thinkquest.org

- String Quartet No. 12 "American" at www

.antonin-dvorak .cz