Surgical suture

| Surgical suture | |

|---|---|

| Intervention | |

|

Surgical suture on needle holder. Packaging shown above. |

Surgical suture is a medical device used to hold body tissues together after an injury or surgery. Application generally involves using a needle with an attached length of thread. A number of different shapes, sizes, and thread materials have been developed over its millennia of history. Surgeons, physicians, dentists, podiatrists, eye doctors, registered nurses and other trained nursing personnel, medics, and clinical pharmacists typically engage in suturing. Surgical knots are used to secure the sutures.

Needles

Eyed or reusable needles are needles with holes called eyes which are supplied separate from their suture thread. The suture must be threaded on site, as is done when sewing at home. The advantage of this is that any thread and needle combination is possible to suit the job at hand. Swaged, or atraumatic, needles with sutures comprise a pre-packed eyeless needle attached to a specific length of suture thread. The suture manufacturer swages the suture thread to the eyeless atraumatic needle at the factory. The chief advantage of this is that the doctor or the nurse does not have to spend time threading the suture on the needle, which may be difficult for very fine needles and sutures. Also, the suture end of a swaged needle is narrower than the needle body, eliminating drag from the thread attachment site. In eyed needles, the thread protrudes from the needle body on both sides, and at best causes drag. When passing through friable tissues, the eye needle and suture combination may thus traumatise tissues more than a swaged needle, hence the designation of the latter as "atraumatic".

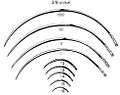

There are several shapes of surgical needles. These include:

- Straight

- 1/4 circle

- 3/8 circle

- 1/2 circle. Subtypes of this needle shape include, from larger to smaller size, CT, CT-1, CT-2 and CT-3.[1]

- 5/8 circle

- compound curve

- half curved (also known as ski)

- half curved at both ends of a straight segment (also known as canoe)

The ski and canoe needle design allows curved needles to be straight enough to be used in laparoscopic surgery, where instruments are inserted into the abdominal cavity through narrow cannulas.

Needles may also be classified by their point geometry; examples include:

- taper (needle body is round and tapers smoothly to a point)

- cutting (needle body is triangular and has a sharpened cutting edge on the inside curve)

- reverse cutting (cutting edge on the outside)

- trocar point or tapercut (needle body is round and tapered, but ends in a small triangular cutting point)

- blunt points for sewing friable tissues

- side cutting or spatula points (flat on top and bottom with a cutting edge along the front to one side) for eye surgery

Finally, atraumatic needles may be permanently swaged to the suture or may be designed to come off the suture with a sharp straight tug. These "pop-offs" are commonly used for interrupted sutures, where each suture is only passed once and then tied.

Eyed surgical needles which form 3/8th of a circle, in different sizes.

Eyed surgical needles which form 3/8th of a circle, in different sizes. Eyed surgical needles which are semicircular, in different sizes.

Eyed surgical needles which are semicircular, in different sizes.

Sutures can withstand different amounts of force based on their size; this is quantified by the U.S.P. Needle Pull Specifications.

Thread

Materials

Suture thread is made from numerous materials. The original sutures were made from biological materials, such as catgut suture and silk. Most modern sutures are synthetic, including the absorbables polyglycolic acid, polylactic acid, Monocryl and polydioxanone as well as the non-absorbables nylon, polyester, PVDF and polypropylene.[2] The FDA first approved triclosan-coated sutures in 2002;[3] they have been shown to reduce the chances of wound infection.[4] Sutures come in very specific sizes and may be either absorbable (naturally biodegradable in the body) or non-absorbable. Sutures must be strong enough to hold tissue securely but flexible enough to be knotted. They must be hypoallergenic and avoid the "wick effect" that would allow fluids and thus infection to penetrate the body along the suture tract.

Absorbability

All sutures are classified as either absorbable or non-absorbable depending on whether the body will naturally degrade and absorb the suture material over time. Absorbable suture materials include the original catgut as well as the newer synthetics polyglycolic acid, polylactic acid, polydioxanone, and caprolactone. They are broken down by various processes including hydrolysis (polyglycolic acid) and proteolytic enzymatic degradation. Depending on the material, the process can be from ten days to eight weeks. They are used in patients who cannot return for suture removal, or in internal body tissues.[5] In both cases, they will hold the body tissues together long enough to allow healing, but will disintegrate so that they do not leave foreign material or require further procedures. Occasionally, absorbable sutures can cause inflammation and be rejected by the body rather than absorbed.

Non-absorbable sutures are made of special silk or the synthetics polypropylene, polyester or nylon. Stainless steel wires are commonly used in orthopedic surgery and for sternal closure in cardiac surgery. These may or may not have coatings to enhance their performance characteristics. Non-absorbable sutures are used either on skin wound closure, where the sutures can be removed after a few weeks, or in stressful internal environments where absorbable sutures will not suffice. Examples include the heart (with its constant pressure and movement) or the bladder (with adverse chemical conditions). Non-absorbable sutures often cause less scarring because they provoke less immune response, and thus are used where cosmetic outcome is important. They may be removed after a certain time, or left permanently.

Sizes

Suture sizes are defined by the United States Pharmacopeia (U.S.P.). Sutures were originally manufactured ranging in size from #1 to #6, with #1 being the smallest. A #4 suture would be roughly the diameter of a tennis racquet string. The manufacturing techniques, derived at the beginning from the production of musical strings, did not allow thinner diameters. As the procedures improved, #0 was added to the suture diameters, and later, thinner and thinner threads were manufactured, which were identified as #00 (#2-0 or #2/0) to #000000 (#6-0 or #6/0).

Modern sutures range from #5 (heavy braided suture for orthopedics) to #11-0 (fine monofilament suture for ophthalmics). Atraumatic needles are manufactured in all shapes for most sizes. The actual diameter of thread for a given U.S.P. size differs depending on the suture material class.

USP

designationCollagen

diameter (mm)Synthetic absorbable

diameter (mm)Non-absorbable

diameter (mm)American

wire gauge11-0 0.01 10-0 0.02 0.02 0.02 9-0 0.03 0.03 0.03 8-0 0.05 0.04 0.04 7-0 0.07 0.05 0.05 6-0 0.1 0.07 0.07 38–40 5-0 0.15 0.1 0.1 35–38 4-0 0.2 0.15 0.15 32–34 3-0 0.3 0.2 0.2 29–32 2-0 0.35 0.3 0.3 28 0 0.4 0.35 0.35 26–27 1 0.5 0.4 0.4 25–26 2 0.6 0.5 0.5 23–24 3 0.7 0.6 0.6 22 4 0.8 0.6 0.6 21–22 5 0.7 0.7 20–21 6 0.8 19–20 7 18

Techniques

Many different techniques exist. The most common is the simple interrupted stitch;[6] it is indeed the simplest to perform and is called "interrupted" because the suture thread is cut between each individual stitch. The vertical and horizontal mattress stitch are also interrupted but are more complex and specialized for everting the skin and distributing tension. The running or continuous stitch is quicker but risks failing if the suture is cut in just one place; the continuous locking stitch is in some ways a more secure version. The chest drain stitch and corner stitch are variations of the horizontal mattress.

Other stitches or suturing techniques include:

- Purse-string suture, a continuous, circular inverting suture which is made to secure apposition of the edges of a surgical or traumatic wound.[7][8]

- Figure 8 stitch

- Subcuticular stitch.

Placement

Sutures are placed by mounting a needle with attached suture into a needle holder. The needle point is pressed into the flesh, advanced along the trajectory of the needle's curve until it emerges, and pulled through. The trailing thread is then tied into a knot, usually a square knot or surgeon's knot. Ideally, sutures bring together the wound edges, without causing indenting or blanching of the skin,[9] since the blood supply may be impeded and thus increase infection and scarring.[10][11] Ideally, sutured skin rolls slightly outward from the wound (eversion), and the depth and width of the sutured flesh is roughly equal.[10] Placement varies based on the location,

Stitching Interval and spacing

Skin and other soft tissue can lengthen significantly under strain. To accommodate this lengthening, continuous stitches must have an adequate amount of slack. Jenkin's Rule was the first research result in this area, showing that the then-typical use of a suture-length to wound-length ratio of 2:1 increased the risk of a burst wound, and suggesting a SL:WL ratio of 4:1 or more in abdominal wounds.[11][12] A later study suggested 6:1 as the optimal ratio in abdominal closure.[13]

Layers

In contrast to single layer suturing, two layer suturing generally involves suturing at a deeper level of a tissue followed by another layer of suturing at a more superficial level. For example, Cesarean section can be performed with single or double layer suturing of the uterine incision.[14]

Removal

Whereas some sutures are intended to be permanent, and others in specialized cases may be kept in place for an extended period of many weeks, as a rule sutures are a short term device to allow healing of a trauma or wound.

Different parts of the body heal at different speeds. Common time to remove stitches will vary: facial wounds 3–5 days; scalp wound 7–10 days; limbs 10–14 days; joints 14 days; trunk of the body 7–10 days.[15]

Removal of sutures is traditionally achieved by using forceps to hold the suture thread steady and pointed scalpel blades or scissors to cut. For practical reasons the two instruments (forceps and scissors) are available in a sterile kit. In certain countries (e.g. USA), these kits are available in sterile disposable trays because of the high cost of cleaning and re-sterilization.

Expansions

A pledgeted suture is one that is supported by a pledget, that is, a small flat non-absorbent pad normally composed of Polytetrafluoroethylene, used as buttresses under sutures when there is a possibility of sutures tearing through tissue.[16]

Tissue adhesives

Topical cyanoacrylate adhesives a.k.a. medicinal grade super glue, have been used in combination with, or as an alternative to, sutures in wound closure. The adhesive remains liquid until exposed to water or water-containing substances/tissue, after which it cures (polymerizes) and forms a bond to the underlying surface. The tissue adhesive has been shown to act as a barrier to microbial penetration as long as the adhesive film remains intact. Limitations of tissue adhesives include contraindications to use near the eyes and a mild learning curve on correct usage. They are also unsuitable for oozing or potentially contaminated wounds.

In surgical incisions it does not work as well as sutures as the wounds often break open.[17]

Cyanoacrylate is the generic name for cyanoacrylate based fast-acting glues such as methyl-2-cyanoacrylate, ethyl-2-cyanoacrylate (commonly sold under trade names like Superglue and Krazy Glue) and n-butyl-cyanoacrylate. Skin glues like Indermil and Histoacryl were the first medical grade tissue adhesives to be used, and these are composed of n-butyl cyanoacrylate. These worked well but had the disadvantage of having to be stored in the refrigerator, were exothermic so they stung the patient, and the bond was brittle. Nowadays, the longer chain polymer, 2-octyl cyanoacrylate, is the preferred medical grade glue. It is available under various trade names, such as LiquiBand, SurgiSeal, FloraSeal, and Dermabond. These have the advantages of being more flexible, making a stronger bond, and being easier to use. The longer side chain types, for example octyl and butyl forms, also reduce tissue reaction.

History

Through many millennia, various suture materials were used, debated, and remained largely unchanged. Needles were made of bone or metals such as silver, copper, and aluminium bronze wire. Sutures were made of plant materials (flax, hemp and cotton) or animal material (hair, tendons, arteries, muscle strips and nerves, silk, and catgut).

The earliest reports of surgical suture date to 3000 BC in ancient Egypt, and the oldest known suture is in a mummy from 1100 BC. A detailed description of a wound suture and the suture materials used in it is by the Indian sage and physician Sushruta, written in 500 BC.[18] The Greek father of medicine, Hippocrates, described suture techniques, as did the later Roman Aulus Cornelius Celsus. The 2nd-century Roman physician Galen described gut sutures.[19] In the 10th century the manufacturing process involved harvesting sheep intestines, the so-called catgut suture, and was similar to that of strings for violins, guitar, and tennis racquets.

Joseph Lister endorsed the routine sterilization of all suture threads. He first attempted sterilization with the 1860s "carbolic catgut," and chromic catgut followed two decades later. Sterile catgut was finally achieved in 1906 with iodine treatment.

The next great leap came in the twentieth century. The chemical industry drove production of the first synthetic thread in the early 1930s, which exploded into production of numerous absorbable and non-absorbable synthetics. The first synthetic absorbable was based on polyvinyl alcohol in 1931. Polyesters were developed in the 1950s, and later the process of radiation sterilization was established for catgut and polyester. Polyglycolic acid was discovered in the 1960s and implemented in the 1970s. Today, most sutures are made of synthetic polymer fibers. Silk and, rarely, gut sutures are the only materials still in use from ancient times. In fact, gut sutures have been banned in Europe and Japan owing to concerns regarding Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy. Silk suture is still used, mainly to secure surgical drains.

See also

References

- ↑ Surgical Needle Guide from Novartis. Copyright 2005.

- ↑ "Types of Sutures". Dolphin Sutures. Retrieved 2014-01-07.

- ↑ ETHICON Products (20 December 2002). "ETHICON Receives FDA Clearance to Market VICRYL* Plus, First Ever Antibacterial Suture". PRNewswire. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ↑ Daoud, FC; Edmiston CE, Jr; Leaper, D (June 2014). "Meta-analysis of prevention of surgical site infections following incision closure with triclosan-coated sutures: robustness to new evidence.". Surgical infections. 15 (3): 165–81. doi:10.1089/sur.2013.177. PMC 4063374

. PMID 24738988.

. PMID 24738988. - ↑ http://teachmesurgery.com/skills/theatre-basics/suture-materials/

- ↑ Lammers, Richard L; Trott, Alexander T (2004). "Chapter 36: Methods of Wound Closure". In Roberts, James R; Hedges, Jerris R. Clinical Procedures in Emergency Medicine (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. p. 671. ISBN 0-7216-9760-7.

- ↑ Dorland's Medical Dictionary for Health Consumers. Copyright 2007

- ↑ Miller-Keane Encyclopedia & Dictionary of Medicine, Nursing, and Allied Health, Seventh Edition.

- ↑ Osterberg, B; Blomstedt, B (1979). "Effect of suture materials on bacterial survival in infected wounds: An experimental study". Acta Chir Scand. 145: 431.

- 1 2 Macht, SD; Krizek, TJ (1978). "Sutures and suturing - Current concepts". Journal of Oral Surgery. 36: 710.

- 1 2 Kirk, RM (1978). Basic Surgical Techniques. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

- ↑ Grossman, JA (1982). "The repair of surface trauma". Emergency Medicine. 14: 220.

- ↑ Varshney, S; Manek, P; Johnson, CD (September 1999). "Six-fold suture:wound length ratio for abdominal closure.". Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 81 (5): 333–6. PMC 2503300

. PMID 10645176.

. PMID 10645176. - ↑ Stark, M.; Chavkin, Y.; Kupfersztain, C.; Guedj, P.; Finkel, A. R. (1995). "Evaluation of combinations of procedures in cesarean section". International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 48 (3): 273–6. doi:10.1016/0020-7292(94)02306-J. PMID 7781869.

- ↑ www.scribd.com

- ↑ "Polytetrafluoroethylene Pledget".

- ↑ Dumville, JC; Coulthard, P; Worthington, HV; Riley, P; Patel, N; Darcey, J; Esposito, M; van der Elst, M; van Waes, OJ (28 November 2014). "Tissue adhesives for closure of surgical incisions.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 11: CD004287. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004287.pub4. PMID 25431843.

- ↑ Mysore, Venkataram. Acs(I) Textbook on Cutaneous and Aesthetic Surgery. Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers Pvt. Ltd. pp. 125–126. ISBN 9789350905913. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ↑ Nutton, Dr Vivia (2005-07-30). Ancient Medicine. Taylor & Francis US. ISBN 9780415368483. Retrieved 21 November 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Surgical suture. |