Sweden during World War I

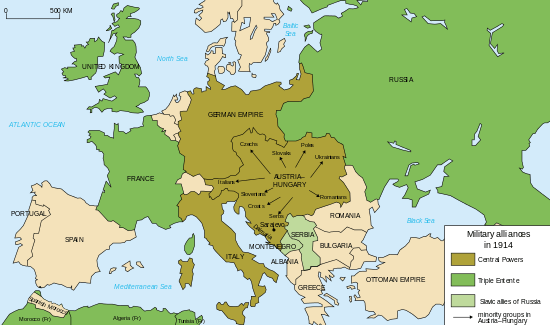

Sweden, following its long-standing policy of neutrality since the Napoleonic Wars, remained neutral throughout World War I between 28 July 1914 and 11 November 1918.[1] However, this neutrality was not maintained without difficulty and Sweden at various times sympathised with different parties in the conflict.

The immediate pre-war period

During the early years of the 20th century the sympathies of the Swedish monarch, King Gustaf V, and of the Swedish military, were believed to be with the Germans due to cultural links and a shared fear of Imperial Russia. Whilst King Gustaf was married to a German (a granddaughter of Kaiser Wilhelm I), the Swedish Riksmarskalk, Ludvig Douglas, was also known to be a strong proponent of an alliance with Germany.[2] In November 1910 the general staffs of Germany and Sweden had even met in secret to discuss a joint offensive against St. Petersburg, although this meeting ended without a binding agreement being reached.[3]

Rearmament was a special concern in Sweden due to growing tensions in Europe. When Karl Staaff's government proposed a reduction in military spending and the cancellation of the order for the coastal battleships that were later known as the Sverige-class coastal defence ship, more than 30,000 Swedish farmers marched to Stockholm to protest in the Peasant armament support march. In response King Gustaf gave a speech written by the ardently pro-German explorer, Sven Hedin in the courtyard of the Royal Palace in Stockholm where he argued for higher military spending.[4]

King Gustaf's "Courtyard Speech" prompted a constitutional crisis in Sweden (the so-called "Courtyard Crisis") due to interference of the crown in the running of the state, as a parliamentary system meant the crown's exclusion from partisan politics. When King Gustaf refused to tone down his rhetoric on the subject of defence spending, Karl Staaff's government resigned and was replaced by the conservative government of Hjalmar Hammarskjöld.[5]

The July Crisis

During the July Crisis, both King Gustaf and Knut Wallenberg, the Swedish foreign minister, gave assurances to the Central Powers that in a war between Germany and Russia, Sweden would never stand on Russia's side, and that although Sweden would issue a declaration of neutrality at the start of the conflict she would retain the freedom to take other action later. The assurances given by King Gustaf and Knut Wallenberg led the German secretary of the foreign ministry, Gottlieb von Jagow, to believe that Germany would be supported by Sweden in the upcoming conflict. Talks even took place between the military and naval staffs of Sweden and Germany on cooperation, and preliminary arrangements were made for Germany to use bases and anchorages on the east cost of Sweden and on the island of Gotland.[5]

Wallenberg also warned the Germans that Sweden could not intervene too soon as this might prompt a British intervention in the conflict, although this in turn led the German minister in Stockholm, Franz von Reichenau, to suggest that if Britain entered the conflict Germany should issue an ultimatum demanding that Sweden join the war. At the same time messages were sent by the Swedish foreign ministry to Russia promising that Sweden would remain neutral, although troops were sent to watch Sweden's frontier with Russian-ruled Finland.[5]

Declarations of Neutrality

Sweden declared neutrality in the Austro-Serbian conflict on 31 July 1914, and in the general conflict of Germany against France and Russia on the 4th of August. Both declarations left open the possibility that Sweden might later change her position if other countries joined the conflict. On the 2nd of August, however, Wallenberg, speaking to the British minister in Stockholm, had repeated his assertion that if Sweden were driven into the war, she would never fight on the side of Russia.[5] Apparently fearful that Germany might issue an ultimatum demanding Sweden choose sides (something the German Kaiser had threatened to do during a visit by King Gustaf to Germany in 1913) Wallenberg also promised Franz von Reichenau that Swedish neutrality would be "benevolent" to Germany.[6]

The position of Norway also concerned Wallenberg, as he believed that the Norwegians would prefer to intervene on the British side if they entered the war. On the 8th of August the two countries (Sweden and Norway) issued a joint declaration of neutrality warning that they would maintain their neutrality against all belligerents and would guarantee each other's neutrality. A further joint declaration was made by the three kings of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden in December 1914, and the Swedish army units that had been sent to the Finnish border were stood down.[2][7]

German offers of an alliance

In early 1915, Arthur Zimmermann, the Under-Secretary of State at the German foreign ministry, approached Hammarskjöld, who was on a visit to Berlin, with an offer of potentially forming a "Nordic Block" under Swedish leadership in return for an alliance between Sweden and Germany. Whilst Hammarskjöld rebuffed this first offer, Zimmermann persisted and approached Ludvig Douglas with an offer for a renewed Swedish Empire covering Finland and the Baltic provinces of the Russian Empire. Douglas then conveyed this offer to King Gustaf on 8 June 1915, and also to Hammarskjöld and Wallenberg, however only King Gustaf received it positively.

Following this failure, Prince Max of Baden, a cousin of the Swedish Queen Victoria, made a further overture to King Gustaf. Prince Max had been instructed by Kaiser Wilhelm II and Erich von Falkenhayn, who wished to integrate Sweden into the German Mitteleuropa, to obtain an alliance with a view to a joint attack on St. Petersburg, in return Germany was willing to offer material and military support as well as the promise of the Aland Islands (which contained a Swedish-speaking population), an adjustment of the frontier, and an independent or autonomous Finland. King Gustaf rejected this offer on 20 November 1915 as, without a clear casus belli, he could not be sure of popular support for the war.[8]

Whilst talk of an alliance eventually came to nothing, Sweden did favour Germany over the western allies in at least one important respect. Knut Wallenberg, without the knowledge of Hammarskjöld, allowed the Germans to use Swedish ciphers to communicate with their embassies overseas, and these communications were carried over the telegraph cables used by Sweden to communicate with their embassies.[8] This allowed the Germans to communicate with their embassies via Stockholm without their communications being so easily censored and intercepted by the British. Despite claiming that they would end the practice in late 1915, a scandal erupted when it became known that a telegram from the German embassy to Berlin proposing that certain Argentine ships be "sunk without trace" had been transmitted via the facilities of the Swedish foreign ministry.[9]

The mining of the Oresund

Throughout the war Germany applied pressure on Sweden and Denmark to close the channels connecting the Baltic sea to the (Allied-dominated) North Sea to Allied warships. Whilst Denmark had given into this pressure and mined the Danish Straits at the outbreak of the war, Sweden resisted demands that its side of the Oresund should be mined.[6]

Eventually Germany relented in return for a promise that Sweden's lighthouses in the Oresund would be switched off and markers showing the way through the channel would be removed if the Royal Navy was sighted in the sound. When Royal Navy submarines entered the Baltic through the sound in October 1914, the Germans demanded that the Swedes carry out their promise.[10]

In October 1915 British submarines operating in the Baltic successfully sank several German cargo ships as well as the armoured cruiser SMS Prinz Adalbert. A German warship opened fire on a Swedish submarine HSwMS Hvalen killing a member of the crew. According to the captain of the Hvalen, the submarine was flying the Swedish naval flag at the time and was sailing in Swedish home waters.[11] Compensation was later paid to the widow of the crew-member and an apology was issued.[12]

In the wake of these sinkings, Germany applied renewed pressure to the Swedes to lay mines in the Oresund channel, and laid mines within the four-mile-limit for territorial waters claimed by Sweden, but outside the three-mile-limit actively enforced by Sweden.[12] Sweden eventually mined the Kogrundsrännan channel running through the Oresund straits in a move announced on 28 July 1916 closing it to all but Swedish ships who would be led through the minefields by pilots.[13] The mining of the channel drew criticism from the Allied powers, causing them to describe Sweden as “neutral with reservations.”[14]

The war-time iron-ore trade

Prior to the outbreak of war, the export of iron-ore from iron-ore mines in two iron-ore fields in Swedish Lapland (Gällivare and Kiruna) had been a major export-business for Sweden. The iron-ore export business was run by an association in which the Swedish government was a member, and production iron-ore for export was fixed at 22,500,000 tons for the period 1907-1938.

The advent of war changed this. The iron-ore fields of Gällivare, which in the year before the war had averaged 1,200,000 tons of iron-ore production, most of which was shipped for export from the port of Luleå on the Baltic, could no longer export to the Allied countries and instead all of their produce went to Germany.

By contrast the iron-ore fields of Kiruna, whose produced was exported through the Norwegian port of Narvik via the North Sea and the Atlantic, became overwhelmingly dominated by exports to the allies, with only 5% of exports going to Germany whereas German exports had previously constituted 70%. At the same time, however, exports through the port slumped, with iron-ore shipments falling from fourteen trains a day to six. The Swedish ships that did continue carrying iron-ore from Narvik to Germany avoided the British blockade by hugging the Norwegian coast and remaining in Norwegian waters as much as possible.[4]

The fall of Hjalmar Hammarskjöld

The entry of the United States into the war on the side of Allies in early 1917 greatly increased the pressure on Sweden to conclude an agreement on trade and shipping favourable to the Allied powers. One specific request was that the Swedish reduce their iron-ore exports to Germany in return for increased supplies of food from the Allies.

Food supplies had become low in Sweden due to the Allied blockade, however Hjalmar Hammarskjöld had continued to resist an agreement that might loosen the blockade in return to reduce exports to Germany due to fear of angering the Germans and being seen as favouring the Allies. Hammarskjöld therefore rejected an agreement to reduce exports to Germany in return for more food negotiated by Marcus Wallenberg (brother of Knut).

Angered by Hammarskjöld's rejection of this agreement, Hammarskjöld's allies in the Swedish parliament rebelled against him. Hammarskjöld was forced to resign and was replaced by Carl Swartz in March 1917. Swartz served as Swedish prime minister for only seven months before being forced from power after the Swedish elections of 1917 and replaced by the liberal government of Nils Edén.[15]

Swedish occupation of the Åland islands

During late 1917, as the German army advanced on the Russian capital of St. Petersburg, Richard von Kühlmann, the new German Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs renewed Germany's offer to champion Swedish sovereignty over the Åland Islands in return for increased support for the German war effort from Sweden that included increased iron-ore exports. Germany's support for Sweden's claim under this proposal would take the form of either occupying the islands and then handing them over to Sweden, or negotiating for their transfer to Sweden in the upcoming peace talks.

With the declaration of Finnish independence on 6 December 1917, and Sweden's recognition of Finland without reservation on the 4th of January, the situation became even more complex. Whilst the Åland islands were linguistically Swedish, and voted for Swedish annexation in a referendum, the Finns claimed the islands as a historical part of the Grand Duchy of Finland.[16]

Knowing that King Gustaf favoured the annexation of the Åland islands to Sweden, von Kühlmann approached King Gustaf with them in secret on 11 November and 17 December 1917. Both King Gustaf and the Swedish government reacted cautiously to these overtures, responding on 23 December with letters to Austria, Turkey, and Germany requesting only that Sweden's interest in the islands be safeguarded, and proposing neutralisation of the islands as the best solution.

This situation changed, however, when, on 13 February 1918, exaggerated reports of atrocities committed on the Åland islands by Russian soldiers prompted the Swedish government to launch a military expedition to the islands. A week later Germany, acting in response to a request for support from the Finnish Whites who also claimed the islands, informed the Swedes that they intended to occupy the islands and that Swedish forces were to leave immediately. This request was eventually modified into an agreement to a joint German-Swedish occupation of the islands that lasted until 25 April 1918, when Swedish forces eventually withdrew in the face of Finnish protests.[17]

See also

References

- ↑ Siney, Marion C. (1975). "Swedish neutrality and economic warfare in World War I". Conspectus of History. 1 (2): 13.

- 1 2 Park, Jihyeon. "Sweden's Neutrality during Two World Wars". Korean Minjok Leadership Academy. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- ↑ Aselius, Gunnar. The Danish Straits and German Naval Power, 1905-1918. Militargeschichtliches Forschungsampt. p. 130.

- 1 2 Curtin, D. Thomas (December 1915). "Sweden's Role in the Great War". The World's Work. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Siney, Marion C. (1975). "Swedish neutrality and economic warfare in World War I". Conspectus of History. 1 (2): 14.

- 1 2 Aselius, Gunnar. The Danish Straits and German Naval Power, 1905-1918. Militargeschichtliches Forschungsampt. p. 132.

- ↑ Siney, Marion C. (1975). "Swedish neutrality and economic warfare in World War I". Conspectus of History. 1 (2): 15.

- 1 2 Salmon, Patrick (1997). Scandinavia and the Great Powers 1890-1940. Cambridge. p. Chapter 4d.

- ↑ Siney, Marion C. (1975). "Swedish neutrality and economic warfare in World War I". Conspectus of History. 1 (2): 16.

- ↑ Aselius, Gunnar. The Danish Straits and German Naval Power, 1905-1918. Militargeschichtliches Forschungsampt. p. 133.

- ↑ "SWEDISH SUBMARINE SHELLED IN HOME WATERS; Hvalen Flying Own Flag and Weather Clear When Germans Fired, Says Captain.". The New York Times. 22 October 1915. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- 1 2 Aselius, Gunnar. The Danish Straits and German Naval Power, 1905-1918. Militargeschichtliches Forschungsampt. p. 134.

- ↑ Halpern, Paul (1994). A Naval History of World War I. United States Naval Institute. p. 211. ISBN 9781612511726.

- ↑ Avedian, Vahagn. "The Armenian Genocide 1915 From a Neutral Small State's Perspective: Sweden" (PDF). Historiska institutionen Uppsala universitet. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- ↑ Scott, Franklin D. (1988). Sweden, the Nation's History. Southern Illinois University. p. 473. ISBN 0809315130.

- ↑ Minahan, James (2002). Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: A-C. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 71. ISBN 0313316171.

- ↑ Salmon, Patrick (1997). Scandinavia and the Great Powers 1890-1940. Cambridge. p. Chapter 4e.