Zaian War

| Zaian War | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the North African theatre of World War I (to 1918) | |||||

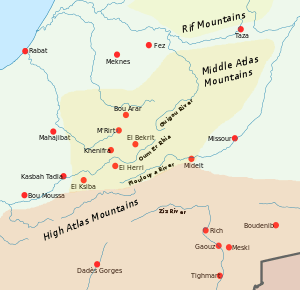

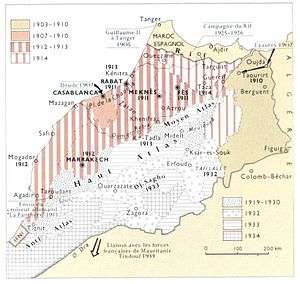

Map showing the area in which the war was fought | |||||

| |||||

| Belligerents | |||||

|

Zaian Confederation Varying other Berber tribes Supported during the First World War by the Central Powers | |||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||

| Strength | |||||

| 95,000 French troops in all of Morocco in 1921[1] | Up to 4,200 tents (approximately 21,000 people) of Zaians at the start of the war[2] | ||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||

|

French dead in the Middle Atlas to 1933:[3] 82 French officers 700 European regulars 1,400 African regulars 2,200 goumiers and partisans | |||||

The Zaian (or Zayan) War was fought between France and the Zaian confederation of Berber tribes in Morocco between 1914 and 1921. Morocco had become a French protectorate in 1912, and Resident-General Louis-Hubert Lyautey sought to extend French influence eastwards through the Middle Atlas mountains towards French Algeria. This was opposed by the Zaians, led by Mouha ou Hammou Zayani. The war began well for the French, who quickly took the key towns of Taza and Khénifra. Despite the loss of their base at Khénifra, the Zaians inflicted heavy losses on the French, who responded by establishing groupes mobiles, combined arms formations that mixed regular and irregular infantry, cavalry and artillery into a single force.

The outbreak of the First World War proved significant, with the withdrawal of troops for service in France compounded by the loss of more than 600 French killed at the Battle of El Herri. Lyautey reorganised his available forces into a "living barricade", consisting of outposts manned by his best troops protecting the perimeter of French territory with lower quality troops manning the rear-guard positions. Over the next four years the French retained most of their territory despite intelligence and financial support provided by the Central Powers to the Zaian Confederation and continual raids and skirmishes reducing scarce French manpower.

After the signing of the Armistice with Germany in November 1918, significant forces of tribesmen remained opposed to French rule. The French resumed their offensive in the Khénifra area in 1920, establishing a series of blockhouses to limit the Zaians' freedom of movement. They opened negotiations with Hammou's sons, persuading three of them, along with many of their followers, to submit to French rule. A split in the Zaian Confederation between those who supported submission and those still opposed led to infighting and the death of Hammou in Spring 1921. The French responded with a strong, three-pronged attack into the Middle Atlas that pacified the area. Some tribesmen, led by Moha ou Said, fled to the High Atlas and continued a guerrilla war against the French well into the 1930s.

Origins

.jpg)

The signing of the Treaty of Fez in 1912 established a French protectorate over Morocco.[4] The treaty had been prompted by the Agadir Crisis of 1911, during which French and Spanish troops had been sent to Morocco to put down a rebellion against Sultan Abdelhafid. The new French protectorate was led by a resident-general, Louis-Hubert Lyautey, and adopted the traditional Moroccan way of governing through the tribal system.[4] Upon taking up his post Lyautey replaced Abdelhafid with his brother, Yusef.[5] The tribes took offence at this, installing their own Sultan, Ahmed al-Hiba, in Marrakesh and taking eight Europeans captive.[5] Lyautey acted quickly against the revolt, dispatching General Charles Mangin and 5,000 troops to retake the town. Mangin's men were highly successful, rescuing the captives and inflicting heavy casualties on vastly superior numbers of tribesmen for the loss of 2 men killed and 23 wounded.[5] Al-Hiba escaped to the Atlas mountains with a small number of his followers and opposed French rule until his death in 1919.[6]

A popular idea among the public in France was to possess an unbroken stretch of territory from Tunis to the Atlantic Ocean, including expansion into the "Taza corridor" in the Moroccan interior.[7] Lyautey was in favour of this and advocated French occupation of the Middle Atlas mountains near Taza, through peaceful means where possible.[8] This French expansion into the Middle Atlas was strongly opposed by the "powerful Berber trinity" of Mouha ou Hammou Zayani, leader of the Zaian Confederation; Moha ou Said, leader of the Aït Ouirra; and Ali Amhaouch, a religious leader of the Darqawa variant of Islam prevalent in the region.[9][10]

Hammou commanded between 4,000 and 4,200 tents[nb 1] of people and had led the Zaians since 1877, opposing the French since the start of their involvement in Morocco.[2] An enemy of the French following their deposing of Sultan Abdelhafid, who was married to Hammou's daughter, he had declared a holy war against them and intensified his tribe's attacks on pro-French (or "submitted") tribes and military convoys.[2][12] Said was an old man, who was held in good standing by tribesmen across the region and had formerly been a caïd (a local governor with almost absolute power) for the Moroccan government, even serving in the army of Sultan Abdelaziz against a pretender at Taza in 1902.[13][14][15] Despite initially being open to negotiations with the French, pressure from pro-war chiefs and the fear of ridicule from his tribesmen had dissuaded him.[13][16][17] Amhaouch was a strong and influential man, described by French officer and explorer René de Segonzac as one of the "great spiritual leaders of Morocco" and the "most powerful religious personality of the south east".[9] The French had attempted to persuade the Zaians to submit since 1913 with little success; most tribes in the confederation remained opposed to French rule.[18]

Lyautey's plans for taking Taza also extended to capturing Khénifra, Hammou's headquarters. He had been advised by his political officer, Maurice Le Glay that doing so would "finish him off definitively" and cut the Zaians off from support of other tribes.[9] The French outpost at nearby Kasbah Tadla had recently been attacked by Said and subsequent peace negotiations led by Lyautey's head of intelligence, Colonel Henri Simon, had achieved little.[19] As a result, Mangin was authorised to lead a retaliatory raid to Said's camp at El Ksiba but, despite inflicting heavy casualties, was forced to withdraw with the loss of 60 killed, 150 wounded and much equipment abandoned.[19] Having failed to make any impression on the Zaians through negotiation in May 1914, Lyautey authorised General Paul Prosper Henrys to take command of all French troops in the area and launch an attack on Taza and Khénifra.[2][8] Henrys captured Taza within a few days using units drawn from garrisons in Fez, Meknes, Rabat and Marrakesh and then turned his attention to Khénifra.[18][20]

Khénifra campaign

Henrys planned his assault on Khénifra to begin on 10 June 1914 with the dispatch of three columns of troops, totalling 14,000 men equipped with wireless radios and supported by reconnaissance aircraft.[8] One column was to set out from Meknes under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Henri Claudel, another from Rabat under Lieutenant-Colonel Gaston Cros and the third from Kasbah Tadla under Colonel Noël Garnier-Duplessix.[21] Henrys took overall command, directing the forces from an armoured car within the Claudel column.[21] Aware that he knew little of the terrain or the allegiance of local tribes Henrys offered a generous set of terms for tribesmen who submitted to French rule: they would have to surrender only their rapid firing rifles and any captured French supplies, and pay a small tax in return for protection.[21] He also set aside substantial funds to bribe informants and tribal leaders.[21]

Despite these measures, Claudel's column came under attack before it even left Meknes, although it was the largest and intended as a diversion.[22] Hammou's forces attacked their camp on three separate nights, inflicting losses of at least one officer and four men killed and nineteen injured, but leaving the other two columns unopposed.[22] Claudel launched a counterattack on 10 June while Hammou was preparing a fourth attack, sweeping the Zaians away with artillery and ensuring little resistance for his march to Khénifra on the next day.[22] After enduring some sniping attacks in Teguet, Claudel's cavalry crossed the Oum er Rbia at el Bordj and advanced to the outskirts of Khénifra.[22] The rest of the column joined them on 12 June, fighting off Zaian attacks on the way and meeting up with the other two columns, finding the town emptied of people and raising the French flag.[22] The column had lost two men killed in the march.[22]

The columns experienced repeated, strong attacks by Zaian tribesmen that day, repelled by late afternoon at the cost of five men killed and nineteen wounded.[22] Further attacks on the nights of 14 and 15 June were repulsed by artillery and machine gun fire, directed by searchlights.[23] Henrys then dispatched two columns south to the Zaian stronghold of Adersan to burn houses, proving his military abilities but not provoking a decisive confrontation with the tribes, who returned to guerrilla warfare tactics.[23] In response all French-controlled markets were closed to the Zaians and their trade convoys were intercepted.[23]

Henrys became aware of a Zaian presence at el Bordj and sent a column to attack them on 31 June. South of el Bordj the French came under heavy fire from tribesmen with modern rifles and resorted to bayonet charges to clear the way.[23] The encounter was Henrys' first major engagement with the Zaians and his losses were high, 1 officer and 16 men killed and a further 2 officers and 75 men wounded.[24] Zaian losses were much higher: the French counted at least 140 dead remaining on the battlefield, and considered the battle a victory.[24] Henrys expected a pause in activity while the Zaians recovered, but instead Hammou stepped up attacks on the French.[24] Just four days later an attack on a French convoy by 500 mounted tribesmen was only repulsed after several hours by more bayonet charges.[24] French losses were again significant with one officer and ten men killed and thirty men wounded.[24]

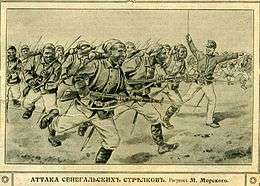

Groupes mobiles

In light of the increased attacks in the Khénifra area Henrys established three groupes mobiles, made up of troops mostly drawn from the Army of Africa.[25] Each groupe was designed to be highly mobile and typically consisted of several battalions of regular infantry (Algerian and Senegalese Tirailleurs or French Foreign Legion troops), a squadron of cavalry (Algerian Spahis), a few batteries of artillery (field or mountain), a section of Hotchkiss machine guns and a mule train for supplies under the overall leadership of a French senior officer.[5][26] In addition each groupe mobile would have one or two goums (informal groups of around 200 men) of goumiers, irregular tribal auxiliaries, under the leadership of a French intelligence officer.[27] The goums were used for intelligence gathering operations and in areas of difficult terrain.[27]

A four-battalion-strong groupe mobile was established at Khénifra, under Lieutenant-Colonel René Laverdure; one based to the west under Claudel and one to the east under Garnier-Duplessix.[24] In addition fortified posts were established at M'Rirt and Sidi Lamine with the areas between patrolled by goumiers to protect convoys and submitted tribes from attack.[25] Increasing attacks on Khénifra throughout July, repelled only by concentrated artillery and machine gun fire, left Henrys concerned that a combined force of tribesmen could threaten the town and the submitted tribes.[28] This fear was partially allayed by the separate defeats of Hammou and Amhaouch by the groupes mobiles of Claudel and Garnier-Duplessix and by increasing numbers of auxiliaries becoming available from newly submitted tribes through the levy system.[25]

Claudel and Garnier-Duplessix were ordered to patrol the French bank of the Oum er Rbia and attempt to separate the Zaians from the Chleuh to the south while Henrys planned for an advance through the Middle Atlas to the Guigou River.[29] These operations were halted by the reduction in forces imposed on him by the outbreak of the First World War in Europe.[29]

First World War

Lyautey received orders from Army headquarters in Paris on 28 July 1914 the day the First World War began, requesting the dispatch of all available troops to France in anticipation of a German invasion and the withdrawal of his remaining forces to more defensible coastal enclaves.[30] The French government justified this stance by stating that the "fate of Morocco will be determined in Lorraine".[31] Lyautey, who had lost most of his own possessions when his house in Crévic had been burnt to the ground by advancing German forces, was keen to support the defence of France and within a month had sent 37 infantry and cavalry battalions and six artillery batteries to the Western Front – more than had been requested of him.[30][32] A further 35,000 Moroccan labourers were recruited by Lyautey over the course of the war for service in France.[33]

Nevertheless, Lyautey did not wish to abandon the inland territory his men had fought so hard for, stating that if he withdrew "such a shock would result immediately all over Morocco ... that a general revolt would arise under our feet, on all our points".[30] Left with just 20 battalions of legionnaires (mainly German and Austrian[nb 2]), military criminals of the Infanterie Légère d'Afrique, territorial reservists, Senegalese Tirailleurs and goumiers, he switched from the offensive to a long-term strategy of "active defence".[31][35] Lyautey withdrew all non-essential personnel from his rear garrisons, brought in elderly reservists from France and issued weapons and elements of military dress to civilians in an attempt to convince the tribes that the French army in Morocco was as strong as before.[31][36] Lyautey referred to this move as similar to hollowing out a lobster while leaving the shell intact.[29] His plan depended on holding a "living barricade" of French outposts running from Taza in the north through Khenifra, Kasbah Tadla and Marrakesh to Agadir on the Atlantic coast.[29]

Lyautey and Henrys intended to hold the Berbers in their current positions until they had sufficient resources to return to the offensive.[24] The recent French advances and troop withdrawals had left Khénifra badly exposed and from 4 August – the day two battalions of infantry left the garrison for France – the Zaian tribes launched a month-long attack on the town, supply convoys and withdrawing French troops "without interruption".[18][29] Lyautey was determined to hold Khénifra to use as a bridgehead for further expansion of French territory and referred to it as a bastion against the "hostile Berber masses" upon which the "maintenance of [his] occupation" depended.[18] Attacks on Khénifra threatened the vital communication corridor between French forces in Morocco and those in Algeria.[18] To relieve pressure on the town, Claudel and Garnier-Duplessix's groupes mobiles engaged Hammou and Amhaouch's forces at Mahajibat, Bou Moussa and Bou Arar on 19, 20 and 21 August, inflicting "considerable losses".[29] This, combined with the reinforcement of Khenifra on 1 September, led to reduced attacks, decreasing to a state of "armed peace" by November.[29]

Henrys began to move towards a more offensive posture, ordering mobile columns to circulate through the Middle Atlas and mounted companies to patrol the plains.[35] This was part of his plan to maintain pressure on Hammou, who he considered to be the linchpin of the "artificial" Zaian Confederation and responsible for their continued resistance.[24][37] Henrys was counting on the onset of winter to force the Zaians from the mountains to their lowland pastures where they could be confronted or persuaded to surrender.[37] In some cases the war assisted Lyautey, allowing him a freer hand in his overall strategy, greater access to finance and the use of at least 8,000 German prisoners of war to construct essential infrastructure.[38][39] In addition the increased national pride led many middle-aged French immigrants in Morocco to enlist in the army and, though they were of poor fighting quality, Lyautey was able to use these men to maintain the appearance of a large force under his command.[40]

Battle of El Herri

When Henrys had successfully repulsed the attacks on Khénifra, he believed he had the upper hand, having proven that the reduced French forces could resist the tribesmen.[41] The Zaians were now contained within a triangle formed by the Oum er Rbia River, the Serrou River and the Atlas Mountains, and were already in dispute with neighbouring tribes over the best wintering land.[41] Hammou decided to winter at the small village of El Herri, 15 kilometres (9 miles) from Khénifra, and established a camp of around 100 tents there.[41][42] Hammou had been promised peace talks by the French, and Lyautey twice refused Laverdure permission to attack him and ordered him to remain on the French bank of the Oum er Rbia.[41][42][43] On 13 November Laverdure decided to disobey these orders and marched to El Herri with almost his entire force, some 43 officers and 1,187 men with supporting artillery and machine guns.[44] This amounted to less than half the force he had in September, when he had last been refused permission to attack.[45]

Laverdure's force surprised the Zaian camp, mostly empty of fighting men, at dawn.[46] A French cavalry charge, followed up with infantry, successfully cleared the camp.[47] After capturing two of Hammou's wives and looting the tents the French started back for Khénifra.[43] The Zaians and other local tribes, eventually numbering 5,000 men, began to converge on the French column and began harassing its flanks and rear.[43][47][48] The French artillery proved ineffective against dispersed skirmishers and at the Chbouka river the rearguard and gun batteries found themselves cut off and overrun.[47] Laverdure detached a small column of troops to take his wounded to Khénifra, remaining behind with the rest of the force.[47] Laverdure's remaining troops were surrounded by the Zaians and were wiped out by a mass attack of "several thousand" tribesmen.[46][47]

The wounded and their escort reached Khenifra safely by noon, narrowly outpacing their pursuers, who had stopped to loot the French dead.[42][47] This force of 431 able-bodied men and 176 wounded were the only French survivors of the battle.[47] The French lost 623 men on the battlefield, while 182 Zaian were killed.[42][49] The French troops also lost 4 machine guns, 630 small arms, 62 horses, 56 mules, all of their artillery and camping equipment and much of their personal belongings.[44][50]

After El Herri

The loss of the column at El Herri, the bloodiest defeat of a French force in Morocco, left Khénifra almost undefended.[51] The senior garrison officer, Captain Pierre Kroll, had just three companies of men to protect the town.[43][47] He managed to inform Lyautey and Henrys of the situation by telegraph before the town came under siege from the Zaians.[43][46] Henrys determined to act quickly against the Zaians to prevent Laverdure's defeat from jeopardising the French presence in Morocco, dispatching Garnier-Duplessix's groupe mobile to Khénifra and forming another groupe in support at Ito under Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Dérigoin.[43][47] Garnier-Duplessix fought his way to the town, relieved it on 16 November, and was joined by Henrys shortly afterwards.[44] The 6th battalion of the 2nd French Foreign Legion Regiment also reached the town, having fought off Zaian attacks during their march from M'Rirt.[35] Henrys led excursions from Khénifra to El Herri as a show of force and to bury their dead, some of whom had been taken as trophies by Hammou to encourage support from other tribes.[44][50]

The Zaian victory at El Herri, combined with slow French progress on the Western Front and the siding of the Muslim Ottoman Empire with the Central Powers, led to an increase in recruits for the tribes and greater co-operation between Hammou, Amhaouch and Said.[52] To counter this Henrys undertook a reorganisation of his forces, forming three military districts centred on Fez, Meknes and Tadla-Zaian (the Khénifra region), the latter under the command of Garnier-Duplessix.[52] Henrys aimed to maintain pressure on Hammou through an economic blockade and the closure of markets to unsubmitted tribes.[52] He imposed a war penalty, in the form of money, horses and rifles, on submitting tribes, believing that their submission would last only if they paid for it.[53] Few tribes took up Henrys' offer and the Zaians continued to cross the Rbia and attack French patrols.[53]

The French returned to the offensive in March with Dérigoin's group sweeping along the French bank of the Rbia, north of Khénifra, and Garnier-Duplessix the left.[53] Dérigoin faced and drove off only a small Zaian force, but Garnier-Duplessix faced a more significant force – his troops were almost overrun by a large mounted group but managed to repulse them, inflicting "serious losses" in return for French casualties of one man killed and eight wounded.[53] Garnier-Duplessix crossed the Rbia again in May to confiscate crops, and was attacked there by a force of 4–5,000 tribesmen at Sidi Sliman, near Kasbah Tadla.[54][55] He repulsed them with artillery and counterattacked successfully over the course of a two-day engagement, killing 300 of the attackers and wounding 400 at the cost of 3 French dead and 5 wounded.[54][55] This victory restored the image of French superiority and led to an increase in tribal submissions, the withdrawal of Said's forces further into the mountains and a six-month period of relative peace.[54] In recognition of this Garnier-Duplessix was promoted to major-general.[54]

The peace was broken on 11 November 1915 by an attack on a supply convoy headed for Khénifra by 1,200–1,500 Zaians and allied tribesmen.[54] The Moroccans pressed to within 50 metres (55 yards) of the French, and Garnier-Duplessix, in command of the convoy, was forced to resort to the bayonet to push them back.[54] French casualties amounted to just 3 killed and 22 wounded but Henrys was concerned by the influence that Hammou continued to hold over other Berber tribes.[54] In retaliation Henrys took both groupes mobiles across the Rbia and bombarded the Zaian camp, inflicting casualties but making little impression on their will to fight.[56] The Zaians recrossed the Rbia in January 1916, camping in French territory and raiding the submitted tribes.[56] Feeling that his communications with Taza were threatened Henrys withdrew his groupes to the Khénifra area, both of them coming under attack en route.[56] At M'Rirt a sizeable Zaian attack was repulsed with 200 casualties but the French suffered the loss of one officer and 24 men killed and 56 wounded.[56]

Lyautey had successfully retained the territory he had captured before the war but was of the opinion that he could not advance any further without risking "an extremely painful" mountain conflict.[56] He faced having his troops withdrawn for service on the Western Front and being left with what he described as "degenerates and outcasts", a loss only partially mitigated by the expansion of the irregular tribal units to 21 goums in strength.[57][58] Henrys accepted an offer of a position in France and was replaced by Colonel Joseph-François Poeymirau, a keen follower of Lyautey who had served as Henrys' second in command at Meknes.[59] Lyautey was offered the post of Minister of War at the invitation of Prime Minister Aristide Briand, which he accepted on 12 December 1916.[56][60] Lyautey was replaced, at his request, by General Henri Gouraud, who had experience fighting alongside Lyautey in Morocco and who had recently returned from the Dardanelles, where he had lost his right arm.[60][61] Lyautey soon became disillusioned with French tactics in Europe, the disunity prevailing between the Allies and his position as a symbolic figurehead of the government.[60][61][62] He was unfamiliar with dealing with political opposition and resigned on 14 March 1917, after being shouted down in the Chamber of Deputies.[63] The government could not survive the resignation of such a senior cabinet member and Briand himself resigned on 17 March, to be replaced by Alexandre Ribot.[63]

Lyautey returned to his former position in Morocco at the end of May and immediately decided on a new strategy. He concentrated his forces in the Moulouya Valley, convinced that the submission of the tribes in this area would lead to the collapse of the Zaian resistance.[60][62][64] In preparation for this new offensive Poeymirau established a French post at El Bekrit, within Zaian territory, and forced the submission of three local tribes.[59] He then used this post to protect his flanks during an advance south-eastwards into the valley, intending to meet with a column led by Colonel Paul Doury, advancing north-west from Boudenib.[59][65] The two columns met at Assaka Nidji on 6 June, a moment which represented the establishment of the first French-controlled route across the Atlas mountains, and earned Poeymirau promotion to brigadier-general.[66] A defensive camp was soon established at Kasbah el Makhzen, and Doury began construction on a road that he promised would be traversable by motor transport by 1918.[59]

By late 1917 motorised lorries were able to traverse much of the road, allowing the French to quickly move troops to areas of trouble and supply their garrisons in eastern Morocco from the west rather than over long routes from the Algerian depots.[66] A secondary road was constructed, leading southwards from the first along the Ziz River, that allowed Doury to reach Er-Rich in the High Atlas, and major posts were established at Midelt and Missour.[66] The Zaians refused to be drawn into attacking the fortified posts that the French built along their new roads, though other tribes launched attacks that summer after rumours of French defeats on the European front.[64] In one instance, in mid-June, it took Poeymirau's entire groupe three days to restore control of the road after an attack.[64]

Doury had expanded the theatre of operations, against Lyautey's orders, by establishing a French mission at Tighmart, in the Tafilalt region, in December 1917 in reaction to a rumoured German presence there.[64] The land here, mainly desert, was almost worthless to the French and Lyautey was keen for his subordinates to focus on the more valuable Moulouya Valley.[67] Local tribes resisted the French presence, killing a translator working at the mission in July 1918.[67] Doury sought to avenge this act on 9 August by engaging up to 1,500 tribesmen, led by Sidi Mhand n'Ifrutant, at Gaouz with a smaller French force that included artillery and aircraft support.[67][68] Entering a thick, jungle-like date palm oasis, one subgroup of Doury's force suffered a close, hard-fought action, hampered by exhaustion and poor supply lines.[64][69] The whole force suffered casualties of 238 men killed and 68 wounded, the worst French losses since the disaster at El Herri, and also lost much of their equipment and transport.[64][70] Lyautey was doubtful of Doury's claim to have almost wiped out his foe, and in response chastised him for his rash action in "this most peripheral of zones" and placed him under Poeymirau's direct command.[67][70] Thus, as the war in Europe was drawing to a close in the early summer of 1918, the French remained hard pressed in Morocco. Despite the death of Ali Amhaouch by natural causes, significant numbers of tribesmen under the leadership of Hammou and Said continued to oppose them.[64]

The Central Powers in Morocco

The Central Powers attempted to incite unrest in the Allied territories in Africa and the Middle East during the war, with the aim of diverting military resources away from the Western Front.[71] German intelligence had identified Northwest Africa as the "Achilles' heel" of the French colonies, and encouraging resistance there became an important objective.[72] Their involvement began in 1914, with the Germans attempting to find a suitable Moroccan leader that they could use to unite the tribes against the French.[73] Their initial choice, former Sultan Abdelaziz, refused to co-operate and moved to the south of France to prevent any further approaches.[73] Instead they entered negotiations with his successor Abdelhafid. He initially co-operated with the Germans, renouncing his former pro-Allied stance in autumn 1914 and moving to Barcelona to meet with officials from Germany, the Ottoman Empire and the Moroccan resistance.[74] During this time he was also selling information to the French.[74] These mixed loyalties came to light when he refused to board a German submarine headed for Morocco, and the Central Powers decided he was of no further use.[74] Abdelhafid then attempted to extort money from the French intelligence services, who responded by halting his pension and arranging his internment at El Escorial.[74] He was later awarded a stipend by Germany in return for his silence on the matter.[74]

The failure to find a suitable leader caused the Germans to alter their plans from a widespread insurrection in Morocco to smaller-scale support of the existing resistance movement.[74] German support included the supply of military advisers and Foreign Legion deserters to the tribes as well as cash, arms and ammunition.[75] Money (in both pesetas and francs) was smuggled into Morocco from the German embassy at Madrid.[76] The money was transferred to Tétouan or Melilla by boat or wired through the telegraph before being smuggled to the tribes, who each received up to 600,000 pesetas per month.[76] Weapons arrived through long-established routes from Spanish Larache or else purchased directly from French gun runners or corrupt Spanish Army troops.[77] The Germans found it hard to get resources to the Zaians in the Middle Atlas due to the distances involved and most of what did get through went to Said's forces.[78] German attempts to distribute supplies inland were frustrated when many tribes hoarded the best resources.[79] Ammunition remained scarce in the Middle Atlas, and many were forced to rely on locally manufactured gunpowder and cartridges.[79]

The Ottoman Empire also supported the Moroccan tribesmen in this period, having provided military training to them since 1909.[80] They co-operated with German intelligence to write and distribute propaganda in Arabic, French and the Middle Atlas Berber dialect.[81] Much of the Ottoman intelligence effort was coordinated by Arab agents operating from the embassy in Madrid and at least two members of the Ottoman diplomatic staff there are known to have seen active service with the tribes in Morocco during the war.[82] Ottoman efforts in Morocco were hindered by internal divisions among the staff, disagreements with their German allies and the outbreak of the Arab Revolt in 1916, with which some of the embassy staff sympathised.[82] These problems led many of the Ottoman diplomatic corps in Spain to leave for America in September 1916, bringing to an end many of the significant Ottoman operations in Morocco.[83]

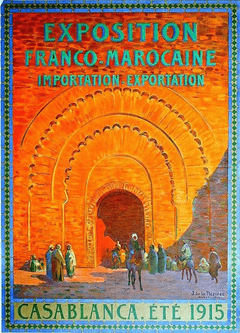

French intelligence forces worked hard to combat the Central Powers and to win the support of the Moroccan people. A series of commercial expositions, such as the Casablanca Fair of 1915, were held to demonstrate the wealth of France and the benefits of co-operation.[84] In addition to stepping up their propaganda campaign and increasing the use of bribes to convince tribes to submit, the French established markets at their military outposts and paid Moroccans to undertake public works.[84] Islamic scholars were also encouraged to issue fatwās supporting the Moroccan Sultan's declaration of independence from the Ottoman Empire.[85]

French and British intelligence agents co-operated in French and Spanish Morocco and Gibraltar, tracking Ottoman and German agents, infiltrating the advisers sent to the tribes and working to halt the flow of arms.[77][86] German citizens in Morocco were placed under careful scrutiny and four were executed within days of the war's start.[87] The French broke the codes used by the German embassy and were able to read almost every communication sent from there to the General Staff in Berlin.[86] Bribes paid to staff at the Ottoman mission to Spain secured intelligence on the Central Powers' plans for Morocco.[86]

Although the efforts of the Central Powers caused a resurgence in resistance against French rule, they were largely ineffective, falling short of the planners' aims of a widespread jihad.[4][88][89] There were few cases of mass civil disorder, France was not required to reinforce the troops stationed in Morocco, and the export of raw materials and labour for the war effort continued.[88] Although they were never able to completely stem the flow of arms, despite considerable effort, the French were able to limit the supply of machine guns and artillery.[79][90] The tribes were thus unable to face the French in direct confrontation and had to continue to rely on ambushes and raids.[90] This contrasted with the Spanish experience in the Rif War of 1920–26, in which tribes with access to such weapons were able to inflict defeats upon the Spanish Army in the field, such as at the Battle of Annual.[90]

Post-war conflicts

The heavy French losses at the Battle of Gaouz encouraged an increase in tribal activity across the south-east of Morocco, threatening the French presence at Boudenib.[1][70] Poeymirau was forced to withdraw garrisons from outlying posts in the Tafilalt, including that at Tighmart, to concentrate his force and reduce the risk of further disasters.[70] Lyautey authorised only a series of limited offensives, such as the razing of villages and gardens, the primary aim of which was to emphasise French military superiority.[91] The French struggled to move troops through the mountain passes from the Moulouya Valley due to heavy snows and attacks on their columns, and Lyautey, to his embarrassment, was forced to request reinforcements from Algeria.[70] By October the situation had stabilised to the extent that Poeymirau was able to withdraw his troops to Meknes, but a large-scale uprising in January 1919 forced his return.[91] Poeymirau defeated n'Ifrutant in battle at Meski on 15 January, but was seriously wounded in the chest by the accidental explosion of an artillery shell and was forced to hand command to Colonel Antoine Huré.[70] Lyautey then received assistance from Thami El Glaoui, a tribal leader who Lyautey had made Pasha of Marrakesh after the uprising of 1912.[92] El Glaoui owed his increasing wealth (when he died in 1956 he was one of the richest men in the world) to corruption and fraud, which the French tolerated in return for his support.[93][94] Thus committed to Lyautey's cause, El Glaoui led an army of 10,000 men, the largest Moroccan tribal force ever seen, across the Atlas to defeat anti-French tribesmen in the Dadès Gorges and to reinforce the garrison at Boudenib on 29 January.[1][70] The uprising was over by 31 January 1919.[91]

The conflict in the Tafilalt distracted the French from their main war aims, draining French reinforcements in return for little economic gain and drawing comparisons to the recent Battle of Verdun.[91] Indeed, the Zaians were encouraged by French losses in the area to renew their attacks on guardposts along the trans-Atlas road.[91] The French continued to hope for a negotiated end to the conflict and had been in discussions with Hammou's close relatives since 1917.[91] Indeed, his nephew, Ou El Aidi, had offered his submission in exchange for weapons and money but had been refused by the French who suspected he wanted to fight with his cousin, Hammou's son, Hassan.[91] With no progress in these negotiations Poeymirau moved against the tribes to the north and south of Khénifra in 1920, the front in this area having remained static for six years.[95] Troops were brought in from Tadla and Meknes to establish blockhouses and mobile reserves along the Rbia to prevent the Zaians crossing to use the pastures.[95] The French were opposed vigorously but eventually established three blockhouses and forced some of the local tribes to submit.[95] French successes in the Khénifra region persuaded Hassan and his two brothers to submit to the French on 2 June 1920, having returned some of the equipment captured at El Herri.[96][97] Hassan was soon appointed Pasha of Khénifra and his 3,000 tents were brought under French protection in an expanded zone of occupation around the Rbia.[96]

Following the submission of his sons, Hammou retained command of only 2,500 tents and in Spring 1921 was killed in a skirmish with other Zaian tribes that opposed continued resistance.[96] The French seized the opportunity to launch an assault on the last bastion of Zaian resistance, located near El Bekrit.[96] In September a three-pronged attack was made: General Jean Théveney moved west from the El Bekrit settlement, Colonel Henry Freydenberg moved east from Taka Ichian and a third group of submitted tribesmen under Hassan and his brothers also took part.[96][98] Théveney encountered resistance from the Zaians in his area but Freydenberg was almost unopposed and within days all resistance was put down.[98] After seven years of fighting the Zaian War was ended, though Lyautey continued his expansion in the area, promising to have all of "useful Morocco" under French control by 1923.[68][98][99] Lyautey had been granted the dignity of a Marshal of France in 1921 in recognition of his work in Morocco.[100]

In Spring 1922, Poeymirau and Freydenberg launched attacks into the headwaters of the Moulouya in the western Middle Atlas and managed to defeat Said, the last surviving member of the Berber triumvirate, at El Ksiba in April 1922.[98][101] Said was forced to flee, with much of the Aït Ichkern tribe, to the highest mountains of the Middle Atlas and then into the High Atlas.[102] Lyautey then secured the submission of several more tribes, constructed new military posts and improved his supply roads; by June 1922, he had brought the entire Moulouya Valley under control and pacified much of the Middle Atlas.[98] Limited in numbers by rapid post-war demobilisation and commitments to garrisons in Germany, he determined not to march through the difficult terrain of the High Atlas but to wait for the tribes to tire of the guerrilla war and submit.[102][103] Said never did so, dying in action against a groupe mobile in March 1924, though his followers continued to cause problems for the French into the next decade.[102][104] Pacification of the remaining tribal areas in French Morocco was completed in 1934, though small armed gangs of bandits continued to attack French troops in the mountains until 1936.[105][106] Moroccan opposition to French rule continued, a plan for reform and return to indirect rule was published by the nationalist Comité d'Action Marocaine (CAM) in 1934, with significant riots and demonstrations occurring in 1934, 1937, 1944 and 1951.[107][108] France, having failed to quell the nationalists by deposing the popular Sultan Mohammed V and already fighting a bloody war of independence in Algeria, recognised Moroccan independence in 1956.[109]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zaian War. |

- The Rif War, a 1920–26 conflict between the Rif people and the Spanish, French, and Jebala people.

Notes

- ↑ A tent is the traditional unit of measure for Berber tribes and holds approximately five persons.[11]

- ↑ The French did not expect men of the foreign legion to have to fight against their own countrymen and so Germans and Austrians, who made up 12% of the total strength of the unit in the war years, were kept away from the western front, with most serving out the war in North Africa.[34]

References

- 1 2 3 Trout 1969, p. 242.

- 1 2 3 4 Hoisington 1995, p. 65.

- ↑ Bidwell 1973, p. 296.

- 1 2 3 Burke 1975, p. 439.

- 1 2 3 4 Bimberg 1999, p. 7.

- ↑ Katz 2006, p. 253.

- ↑ Gershovich 2005, p. 100.

- 1 2 3 Bimberg 1999, p. 9.

- 1 2 3 Hoisington 1995, p. 63.

- ↑ Fage, Roberts & Oliver 1986, p. 290.

- ↑ Trout 1969, p. 78.

- ↑ Slavin 2001, p. 119.

- 1 2 Hoisington 1995, p. 59.

- ↑ Singer & Langdon 2004, p. 196.

- ↑ Bidwell 1973, p. 75.

- ↑ Singer & Langdon 2004, p. 197.

- ↑ Bidwell 1973, p. 34.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gershovich 2005, p. 101.

- 1 2 Bimberg 1999, p. 8.

- ↑ Hoisington 1995, p. 64.

- 1 2 3 4 Hoisington 1995, p. 66.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hoisington 1995, p. 67.

- 1 2 3 4 Hoisington 1995, p. 69.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Hoisington 1995, p. 70.

- 1 2 3 Bimberg 1999, p. 10.

- ↑ Bimberg 1999, p. 5.

- 1 2 Bimberg 1999, p. 6.

- ↑ Hoisington 1995, p. 72.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hoisington 1995, p. 73.

- 1 2 3 Burke 1975, p. 441.

- 1 2 3 Gershovich 2005, p. 102.

- ↑ Singer & Langdon 2004, p. 210.

- ↑ De Haas 2007, p. 45.

- ↑ Windrow 2010, p. 424.

- 1 2 3 Windrow & Chappell 1999, p. 10.

- ↑ Windrow 2010, p. 423.

- 1 2 Hoisington 1995, p. 71.

- ↑ Singer & Langdon 2004, p. 205.

- ↑ Jones 2011, p. 111.

- ↑ Singer & Langdon 2004, p. 204.

- 1 2 3 4 Hoisington 1995, p. 74.

- 1 2 3 4 French Embassy in Morocco, Le Maroc sous domination coloniale (pdf) (in French), retrieved 29 November 2009

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bimberg 1999, p. 11.

- 1 2 3 4 Hoisington 1995, p. 76.

- ↑ Hoisington 1995, p. 77.

- 1 2 3 Gershovich 2005, p. 103.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Hoisington 1995, p. 75.

- ↑ Military Intelligence Division, General Staff 1925, p. 403.

- ↑ McDougall 2003, p. 43.

- 1 2 Lázaro 1988, p. 98.

- ↑ Jaques 2007a, p. 330.

- 1 2 3 Hoisington 1995, p. 80.

- 1 2 3 4 Hoisington 1995, p. 81.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hoisington 1995, p. 82.

- 1 2 Jaques 2007c, p. 941.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hoisington 1995, p. 83.

- ↑ Singer & Langdon 2004, p. 206.

- ↑ Bimberg 1999, p. 12.

- 1 2 3 4 Hoisington 1995, p. 84.

- 1 2 3 4 Singer & Langdon 2004, p. 207.

- 1 2 Windrow 2010, p. 438.

- 1 2 Tucker 2005, p. 726.

- 1 2 Woodward 1967, p. 270.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hoisington 1995, p. 85.

- ↑ Windrow 2010, p. 441.

- 1 2 3 Windrow 2010, p. 442.

- 1 2 3 4 Hoisington 1995, p. 86.

- 1 2 Jaques 2007b, p. 383.

- ↑ Windrow 2010, p. 449.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Windrow 2010, p. 452.

- ↑ Burke 1975, p. 440.

- ↑ Lázaro 1988, p. 96.

- 1 2 Burke 1975, p. 444.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Burke 1975, p. 445.

- ↑ Burke 1975, p. 447.

- 1 2 Burke 1975, p. 454.

- 1 2 Burke 1975, p. 451.

- ↑ Burke 1975, p. 448.

- 1 2 3 Burke 1975, p. 452.

- ↑ Burke 1975, p. 458.

- ↑ Burke 1975, p. 455.

- 1 2 Burke 1975, p. 459.

- ↑ Burke 1975, p. 460.

- 1 2 Burke 1975, p. 449.

- ↑ Burke 1975, p. 456.

- 1 2 3 Burke 1975, p. 450.

- ↑ Strachan 2003.

- 1 2 Burke 1975, p. 457.

- ↑ Lázaro 1988, p. 93.

- 1 2 3 Burke 1975, p. 453.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hoisington 1995, p. 87.

- ↑ Pennell 2000, p. 163.

- ↑ Kveder, Bojan (28 June 2010), "Reviving the last Pasha of Marrakech", BBC News, retrieved 8 December 2012

- ↑ Pennell 2000, p. 184.

- 1 2 3 Hoisington 1995, p. 88.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hoisington 1995, p. 89.

- ↑ Bimberg 1999, p. 13.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hoisington 1995, p. 90.

- ↑ Windrow 2010, p. 458.

- ↑ Windrow 2010, p. 456.

- ↑ Windrow 2010, p. 466.

- 1 2 3 Hoisington 1995, p. 92.

- ↑ Trout 1969, p. 243.

- ↑ Bimberg 1999, p. 14.

- ↑ Bidwell 1973, p. 77.

- ↑ Windrow 2010, p. 603.

- ↑ Bidwell 1973, p. 335.

- ↑ Segalla 2009, p. 212.

- ↑ Country Profile: Morocco (PDF), Library of Congress – Federal Research Division, retrieved 6 April 2013

Bibliography

- Bidwell, Robin Leonard (1973), Morocco Under Colonial Rule: French Administration Of Tribal Areas 1912–1956, Abingdon, UK: Frank Cass, ISBN 0-7146-2877-8

- Bimberg, Edward L. (1999), The Moroccan Goums: Tribal Warriors in a Modern War, Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-30913-2

- Burke, Edmund (1975), "Moroccan Resistance, Pan-Islam and German War Strategy, 1914–1918", Francia, 3: 434–464, ISSN 0251-3609

- Fage, J.D.; Roberts, Andrew; Oliver, Roland Anthony (1986), The Cambridge History of Africa: From 1905 to 1940, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-22505-1

- Gershovich, Moshe (2005), French Military Rule in Morocco: Colonialism and its Consequences, Abingdon, UK: Frank Cass, ISBN 0-7146-4949-X

- De Haas, Hein (2007), "Morocco's migration experience: a transitional perspective", International Migration, 45 (4): 39–70, doi:10.1111/j.1468-2435.2007.00419.x, ISSN 1468-2435

- Hoisington, William A (1995), Lyautey and the French Conquest of Morocco, New York: Macmillan (St Martin's Press), ISBN 0-312-12529-1

- Jaques, Tony (2007a), Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: A-E, Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-33537-0

- Jaques, Tony (2007b), Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: F-O, Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-33537-0

- Jaques, Tony (2007c), Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: P-Z, Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-33537-0

- Jones, Heather (2011), Violence Against Prisoners of War in the First World War: Britain, France and Germany, 1914–1920, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-11758-6

- Katz, Jonathan G. (2006), Murder in Marrakesh: Émile Mauchamp and the French Colonial Adventure, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, ISBN 0-253-34815-3

- Lázaro, Fabio T. López (1988), From the A'Yan to Amir: The Abd Al-Karim of the Moroccan Rif, 1900 to 1921 (PDF), Master of Arts Thesis, Simon Fraser University, OCLC 22381017

- McDougall, James (2003), Nation, Society and Culture in North Africa, London: Frank Cass, ISBN 0-7146-5409-4

- Military Intelligence Division, General Staff (July–August 1925), "Foreign Military Notes" (PDF), The Field Artillery Journal, 15 (4): 395–404, ISSN 0899-2525

- Pennell, C.R. (2000), Morocco Since 1830: A History, London: C. Hurst & Co, ISBN 1-85065-273-2

- Segalla, Spencer D. (2009), Moroccan Soul: French Education, Colonial Ethnology, and Muslim Resistance 1912-1956, Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 978-0-8032-1778-2

- Singer, Barnett; Langdon, John W. (2004), Cultured Force: Makers and Defenders of the French Colonial Empire, Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, ISBN 0-299-19900-2

- Slavin, David Henry (2001), Colonial Cinema and Imperial France, 1919–1939: White Blind Spots, Male Fantasies, Settler Myths, Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-6616-2

- Strachan, Hew (2003), The First World War: To Arms, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-820877-4

- Trout, Frank E. (1969), Morocco's Saharan Frontiers, Geneva: Librairie Droz, ISBN 978-2-600-04495-0

- Tucker, Spencer C. (editor) (2005), The Encyclopedia of World War One, Santa Barbara, California: ABC CLIO, ISBN 978-1-85109-420-2

- Windrow, Martin; Chappell, Mike (1999), French Foreign Legion 1914–1945, Oxford: Osprey, ISBN 1-85532-761-9

- Windrow, Martin (2010), Our Friends Beneath the Sands, London: Phoenix, ISBN 978-0-7538-2856-4

- Woodward, Sir Llewellyn (1967), Great Britain and War of 1914–1918, Frome, Somerset & London: Butler & Tanner, ISBN 0-416-42400-7