Tailteann Games

The Tailteann Games, Tailtin Fair, Áenach Tailteann, Aonach Tailteann, Assembly of Talti, Fair of Talti or Festival of Talti were funeral games associated with the semi-legendary history of Pre-Christian Ireland.

There is a complex of ancient earthworks dating to the Iron Age in the area of Teltown where the festival was historically known to be celebrated off and on from medieval times into the modern era.[1][2][3]

History and archaeology

The games were founded, according to the Book of Invasions, by Lugh Lámhfhada, the Ollamh Érenn (master craftsman or doctor of the sciences), as a mourning ceremony for the death of his foster-mother Tailtiu. Lugh buried Tailtiu underneath a mound in an area that took her name and was later called Teltown in County Meath.[4] Part of one of the mounds in the area called the Knockauns was partially destroyed by bulldozers for urbanization in 1997. John O'Donovan claimed that loughs near a fort in the area called the Rath Dhubh "have the appearance of being artificial lakes and may have been used when the Olympic Games of Tailteann were celebrated by the Irish." He also mentions a tradition that the shade of Laogaire, the King of Tara, was imprisoned by Saint Patrick until Judgement Day to the east of Rath Dhubh in the Dubhloch.[3]

The event was held during the last fortnight of July and culminated with the celebration of Lughnasadh, or Lammas Eve (1 August).[5] Modern folklore claims that the Tailteann Games started around 1600 BC, with some sources claiming as far back as 1829 BC.[6][7][8][9][10][11][12] Promotional literature for the Gaelic Athletic Association revival of the games in 1924 claimed a later date of their foundation in 632 BC. The games were known to have been held between the 6th and 9th centuries AD.[13] The games were held until 1169-1171 AD when they died out after the Norman invasion.[14][15]

The ancient Aonach had three functions: honoring the dead, proclaiming laws, and funeral games and festivities to entertain. The first function took between one and three days depending on the importance of the deceased. Guests would sing mourning chants called the Guba, after which druids would improvise Cepógs, songs in memory of the dead. The dead would then be burnt on a funeral pyre. The second function would then be carried out during a universal truce by the Ollamh Érenn, giving out laws to the people via bards and druids and culminating in the igniting of another massive fire. The custom of rejoicing after a funeral was then enshrined in the Cuiteach Fuait, games of mental and physical ability.[1]

Games included the long jump, high jump, running, hurling, spear throwing, boxing, contests in swordfighting, archery, wrestling, swimming, and chariot and horse racing. They also included competitions in strategy, singing, dancing and story-telling, along with crafts competitions for goldsmiths, jewellers, weavers and armourers. Along with ensuring a meritocracy, the games would also feature a mass arranged marriage, where couples met for the first time and were given up to a year and a day to divorce on the hills of separation.[1]

In later medieval times, the games were revived and called the Tailten Fair, consisting of contests of strength and skill, horse races, religious celebrations, and a traditional time for couples to contract "Handfasting" trial marriages. "Taillten marriages" were legal up until the 13th century. This trial marriage practice is documented in the fourth and fifth volumes of the Brehon law texts, which are compilations of the opinions and judgements of the Brehon class of Druids (in this case, Irish). The texts as a whole deal with a copious amount of detail for the Insular Celts.[16]

Revival attempts

A report to revive the games was debated in the Dáil in June 1922. Modern sports such as motorcycling and shooting were to be included, along with a parade of massed choirs. The possibility of out-doing the Olympic Games was mentioned: "We have got representations from America to the effect that it would be advisable to depart from the idea of confining the Tailteann games to the Irish race and seeing that they predated the Greek Olympic by a thousand years we should be justified in entering upon a more varied programme."[17] The games were delayed by the Irish Civil War of 1922-23.

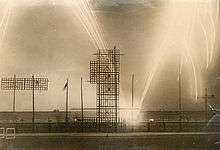

A sporting festival bearing the same name was held by the Gaelic Athletic Association in Croke Park in 1924, 1928, and 1932 and was open to all people of Irish birth or ancestry, with participants coming from England, Scotland, Wales, Canada, the USA, South Africa and Australia as well as Ireland.[18] Chess competitions were held in conjunction with the Irish Chess Union as part of the Tailteann Games.

Events, Sailing

The Sailing event of 1924 was sailed in Kingstown (now Dún Laoghaire) on Saturday evening on the second week of August, using the dinghies designed for use on the river Shannon, the Shannon-One-Design. Seven boats took place. Result: 1st. S47 Major Edgar H. Waller, 2nd. S32 N. + Lionel Lyster, 3rd. S.35 Major A.G. Waller, 4th. S36 Mr. R. White, 5th.S34 Mr. Walter Levinge, 6th. S45 Mr. Tom Feely, 7th. S43 Major Jocelyn H.De W. Waller.,

Events, Motor Boating

The Motor Boat event of 1924 took place in Dublin Bay.

The Motor Boat event of 1928 took place at Ballyglass, Co. Westmeath, home of the Lough Ree Yacht Club, and Motor Yacht Club of Ireland, on 16 August. Races took place in various classes:

- Race 1. Free for all sweepstakes. 1st. 'Fiend' J.W. Shillan. 2nd. 'Irish Express' Major H. Waller. 3rd. 'Miss Chief' J. C. Healy.

- Race 2. Handicap for boats with outboard engines not exceeding 350cc. Boat min. weight 120 lbs. 1st. 'Miss Chief' J.C. Healy. 2nd. 'Busy Bee' Lt. Col. Mansfield. 3rd. 'Imp' D. Tidmarsh.

- Race 3. Handicap for boats with inboard engines exceeding 20'-0". 1st. 'Shrike' Lt. Col. Mansfield. 2nd.'La Vague' Dr. V. S. Delany. 3rd. 'Janet' J. C. Healy.

- Race 4. Handicap for boats with outboard engines of unlimited cc. Boat min. weight 140 lbs. 1st. 'Baby Costume' L. Hogan. 2nd.'Fiend' J. W. Shillan. 3rd. 'Busy Bee' Lt. Col. Mansfield.

- Race 5. Free for all scratch race. Outboard engines. 1st. 'Fiend' J. W. Shillan. 2nd. 'Miss Chief' J. C. Healy. 3rd. 'Busy Bee' Lt. Col. Mansfield.

- Race 6. Handicap race for boats with inboard engines, length not exceeding 20 ft. 1st. 'Udra' Dr. V.S. Delany. 2nd. 'Mermaid' Mr. J. Ryan.

History

This revival "meeting of the Irish race" was announced by Éamon de Valera in Dáil Éireann in 1921. However, due to the Anglo-Irish War and Civil War it was not held until 1924.[19] The meeting was launched to celebrate the independence of Ireland. The Hogan Stand was built and opened for the 1924 games.[18]

The Games coincided in timing with the Olympics, so many athletes participating in the Paris and Amsterdam Olympics came to Dublin to compete, including Harold Osborne, the American high jumper, who won the High Jump titles at Paris 1924 and Tailteann Games 1924.

The 1924 Tailteann Games had a cultural by-programme, during which two recent operas by Irish composers were performed: Geoffrey Molyneux Palmer's Srúth na Maoile (1922) and Harold White's Seán the Post (1924), along with Shamus O'Brien (1896) by Charles V. Stanford, but it was not successful: "[...] there seemed to be a greater number of people in the orchestra than in the audience".[20]

Modern athletics meetings of the same name

A modern athletics meet of the same name is held every year under the auspices of Athletics Ireland, and is organised as an inter-provincial competition.[21]

Annalistic references

- AI875.1 Kl. Muiredach son of Bran, king of Laigin, harried UíNéill as far as Sliab Fuait, and the Fair of Tailltiu was held.

Notes

- 1 2 3 T. H. Nally (30 June 2008). The Aonac Tailteann and the Tailteann Games, Their History and Ancient Associations. Jesson Press. ISBN 978-1-4097-8189-9. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ↑ Tailteann Games place in history going for a song By Seán Diffley, Irish Independent, Saturday July 14, 2007

- 1 2 Malcolm, Nigel., & Quinn, Billy., Teltown Impact Assessment Report, 2009.

- ↑ Lebor Gabála Érenn, original text edited and translated by R A Stewart Macalister, D. Litt, Part IV: Irish Texts Society, Volume 41, pp. 59, 115, 117, 149, 177, 179, London 1941. ISBN 1-870166-41-8.

- ↑ Geoffrey Keating (1866). Foras feasa ar Eirinn ... The history of Ireland, tr. and annotated by J. O'Mahony. pp. 301–. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- ↑ Tim Delaney; Tim Madigan (30 April 2009). The Sociology of Sports: An Introduction. McFarland. pp. 42–. ISBN 978-0-7864-4169-3. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- ↑ William H. Freeman (21 January 2011). Physical Education, Exercise and Sport Science in a Changing Society. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. pp. 80–. ISBN 978-0-7637-8157-6. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- ↑ Peter Matthews (22 March 2012). Historical Dictionary of Track and Field. Scarecrow Press. pp. 2–. ISBN 978-0-8108-6781-9. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- ↑ Martin Connors; Diane L. Dupuis; Brad Morgan (1992). The Olympics factbook: a spectator's guide to the winter and summer games. Visible Ink. ISBN 978-0-8103-9417-9. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- ↑ Terence Brown (1985). Ireland: a social and cultural history, 1922-1985, p. 82. Fontana Press. ISBN 978-0-00-686082-2. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ↑ H. E. L. Mellersh; Neville Williams (1 April 1999). Chronology of world history, p. 15. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-155-7. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ↑ Grolier Incorporated (2000). The Encyclopedia Americana, pp. 892 & 905. Grolier. ISBN 978-0-7172-0133-4. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ↑ John T. Koch (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 777–. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ↑ "The Tailteann Games, 1924-1936". The Irish Story.

- ↑ Melvyn Watman, History of British Athletics. Hale, London, 1968.

- ↑ O'Donovan, J., O'Curry, E., Hancock, W. N., O'Mahony, T., Richey, A. G., Hennessy, W. M., & Atkinson, R. (eds.) (2000). Ancient laws of Ireland, published under direction of the Commissioners for Publishing the Ancient Laws and Institutes of Ireland. Buffalo, New York: W.S. Hein. ISBN 1-57588-572-7. (Originally published: Dublin: A. Thom, 1865-1901. Alternatively known as Hiberniae leges et institutiones antiquae.)

- ↑ "Dil ireann - Volume 2 - 08 June, 1922 - IOMATHOIRI IASACHTA.". oireachtas.ie.

- 1 2 History of Croke Park - Hogan Stand

- ↑ The Tailteann Games - An Olympic Event for the "Celtic Race", by Bernd Biege, About.com

- ↑ Joseph O'Neill: "Music in Dublin", in: Music in Ireland. A Symposium, ed. by Aloys Fleischmann (Cork: Cork University Press, 1952), p. 255.

- ↑ Athletics Association of Ireland

References

- Lewis Spence, The History and Origins of Druidism

- Elizabeth Pepper and John Wilcock, Magical and Mystical Sites

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |