Tenmoku

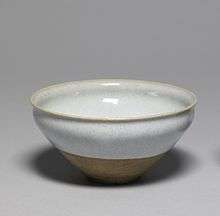

Tenmoku (天目, also spelled "temmoku" and "temoku") is a type of Japanese pottery and porcelain that originates from Chinese Jian ware (建盏) of the southern Song dynasty (1127–1279).[1]

History

Tenmoku takes its name from the Tianmu Mountain (天目Mandarin: tiān mù; Japanese: ten moku; English: Heaven's Eye) temple in China where iron-glazed bowls were used for tea. The style became widely popular during the Song dynasty. In Chinese it is called Jian Zhan (建盏),[2] which means "Jian (tea)cup".[3]

According to chronicles in 1406, the Yongle Emperor (1360–1424) of the Ming dynasty bestowed ten Jian ware bowls to the Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu (1358-1408), who ruled during the Muromachi period. A number of Japanese monks who traveled to monasteries in China also brought pieces back home.[4] As they became valued for tea ceremonies, more pieces were imported from China where they became highly prized goods. Five of these vessels from the southern Song dynasty are so highly valued that they were included by the government in the list of National Treasures of Japan (crafts: others).

The style was eventually produced in Japan as well, where it endures until this day. The Japanese term gradually replaced the original Chinese one for general ware of the type. Of particular renown were the kilns that produced tenmoku are Seto ware.

The glaze is still produced in Japan amongst a very small circle of artists, one of particular renown being Kamada Kōji (鎌田幸二).[5]

Characteristics

It is made of feldspar, limestone, and iron oxide. The more quickly a piece is cooled, the blacker the glaze will be.

Tenmokus are known for their variability. During their heating and cooling, several factors influence the formation of iron crystals within the glaze. A long firing process and a clay body which is also heavily colored with iron increase the opportunity for iron from the clay to be drawn into the glaze. While the glaze is molten, iron can migrate within the glaze to form surface crystals, as in the "oil spot" glaze, or remain in solution deeper within the glaze for a rich glossy color.

Today, most potters are familiar with tenmoku glaze in a reduction firing. But to get oil spot effects, stiff tenmokus need to be fired in oxidation. This relies on a very simple chemical principle that, once understood, leads to successful firings. Red iron oxide (Fe2O3) acts as a refractory in oxidation but it can easily be changed to a flux in the form of black iron oxide (FeO), in reduction. Most potters are familiar with this property but for oil spots, we are interested in iron’s ability to self-reduce. At approximately cone 7 (2250 °F or 1232 °C), ferric iron (Fe2O3) cannot maintain its trigonal crystalline structure and rearranges to a cubic structure, magnetite (Fe3O4), which further reduces to become ferrous (FeO). This is called thermal reduction, and what this means in layman’s terms is that, when it is sufficiently heated, the red iron oxide used in the glaze recipe will naturally let go of an oxygen atom. As the liberated oxygen bubbles rise to the surface of the glaze, they drag a bit of the magnetite with them and deposit it on the surface. A rough black spot is left on the glaze surface that is a different color than the surrounding glaze, due to the larger concentration of iron oxide in that small area and its subsequent re-oxidization during cooling.[6]

A longer cooling time allows for maximum surface crystals. Potters can "fire down" a kiln to help achieve this effect. During a normal firing, the kiln is slowly brought to a maximum temperature by adding fuel, then fueling is stopped and the kiln is allowed to cool slowly by losing heat to the air around it. To fire down a kiln, the potter continues to add a limited amount of fuel after the maximum temperature is reached to slow the cooling process and keep the glazes molten for as long as possible.

Tenmoku glazes can range in color from dark plum (persimmon), to yellow, to brown, to black.

References

- ↑ https://www.britannica.com/art/Jian-ware-Chinese-stoneware

- ↑ http://www.koh-antique.com/jian/jian.html

- ↑ http://gotheborg.com/glossary/temmoku.shtml

- ↑ http://www.chinaheritagequarterly.org/features.php?searchterm=029_li.inc&issue=029

- ↑ http://www.e-yakimono.net/guide/html/tenmoku.html

- ↑ Ceramics Monthly, "Oil Spot and Hare’s Fur Glazes: Demystifying Classic Ceramic Glazes", John Britt, April 13, 2011.

Further reading

- "The Complete Guide to High Fire Glazes", John Britt, Lark Books 2004, Oil Spot Glazes page 75 - 77.

External links

![]() Media related to Tenmoku at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tenmoku at Wikimedia Commons

- Tenmoku ware at the Kyoto National Museum

- Web page about modern tenmoku works by Kamada Kōji

- http://www.e-yakimono.net/guide/html/tenmoku.html