The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

1st edition cover | |

| Author | Victor Hugo |

|---|---|

| Original title | Notre-Dame de Paris |

| Translator | Frederic Shoberl (English) |

| Illustrator | Luc-Olivier Merson (original) |

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

| Genre | Romanticism, Gothic fiction |

| Set in | Paris, 1482 |

| Publisher | Gosselin |

Publication date | 14 January 1831 |

Published in English | 1833 |

| Media type | Hardback |

| Pages | 940, in 3 volumes |

| 843.7 | |

The Hunchback of Notre-Dame (French: Notre-Dame de Paris) is a French Romantic/Gothic novel by Victor Hugo, published in 1831. The original French title refers to Notre Dame Cathedral, on which the story is centered. English translator Frederic Shoberl named the novel The Hunchback of Notre Dame in 1833 because at the time, Gothic novels were more popular than Romance novels in England.[1] The story is set in Paris, France in the Late Middle Ages, during the reign of Louis XI.

Background

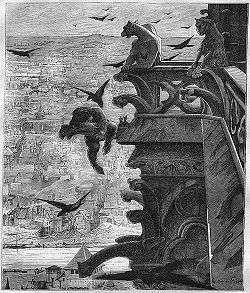

Victor Hugo et son temps (1881)

Victor Hugo began writing Notre-Dame de Paris in 1829, largely to make his contemporaries more aware of the value of the Gothic architecture, which was neglected and often destroyed to be replaced by new buildings, or defaced by replacement of parts of buildings in a newer style. For instance, the medieval stained glass panels of Notre-Dame de Paris had been replaced by white glass to let more light into the church.[2] This explains the large descriptive sections of the book, which far exceed the requirements of the story. A few years earlier, Hugo had already published a paper entitled Guerre aux Démolisseurs (War to the Demolishers) specifically aimed at saving Paris' medieval architecture.[3] The agreement with his original publisher, Gosselin, was that the book would be finished that same year, but Hugo was constantly delayed due to the demands of other projects. In the summer of 1830 Gosselin demanded that Hugo complete the book by February 1831. Beginning in September 1830, Hugo worked nonstop on the project thereafter. The book was finished six months later.

Plot

The gypsy Esmeralda captures the hearts of many men, including those of Captain Phoebus and Pierre Gringoire, but especially Quasimodo and his guardian Archdeacon Claude Frollo. Frollo is torn between his obsessive lust for Esmeralda and the rules of the Notre Dame Cathedral. He orders bandits to kidnap her, but the hunchback is captured by Phoebus and his guards, who save Esmeralda.

The following day, Quasimodo is sentenced to be flogged and turned on the pillory for one hour, followed by another hour's public exposure. He calls for water. Esmeralda, seeing his thirst, approaches the public stocks and offers him a drink of water. It saves him, and she captures his heart.

Later, Esmeralda is arrested and charged with the attempted murder of Phoebus, whom Frollo actually attempted to kill in jealousy after seeing him trying to seduce Esmeralda. She is sentenced to death by hanging. As she is being led to the gallows, Quasimodo swings down by the bell rope of Notre-Dame and carries her off to the cathedral under the law of sanctuary, temporarily protecting her from arrest.

Frollo later informs Gringoire that the Court of Parlement has voted to remove Esmeralda's right to sanctuary so she can no longer seek shelter in the cathedral and will be taken away to be killed. Clopin, the leader of the Gypsies, hears the news from Gringoire and rallies the citizens of Paris to charge the cathedral and rescue Esmeralda.

When Quasimodo sees the Gypsies, he assumes they are there to hurt Esmeralda, so he drives them off. Likewise, he thinks the King's men want to rescue her, and tries to help them find her. She is rescued by Frollo and her phony husband Gringoire. But after yet another failed attempt to win her love, Frollo betrays Esmeralda by handing her to the troops and watches while she is being hanged.

When Frollo laughs during Esmeralda's hanging, Quasimodo pushes him from the heights of Notre Dame to his death. Quasimodo later goes to Montfaucon, a huge graveyard in Paris where the bodies of the condemned are dumped, where he stays with Esmeralda's dead body and dies of starvation. About eighteen months later, the tomb is opened, and the skeletons are found. As someone tries to separate them, they crumble to dust.

Characters

- Quasimodo is the bell-ringer of Notre Dame and a barely verbal and half-blind hunchback. Ringing the church bells has made him deaf. Abandoned by his mother as a baby, he was adopted by Claude Frollo. Quasimodo's life within the confines of the cathedral and his only two outlets — ringing the bells and his love and devotion for Frollo — are described. He ventures outside the Cathedral rarely, since people despise and shun him for his appearance. The notable occasions when he does leave are his taking part in the Festival of Fools — during which he is elected the Pope of Fools due to his perfect hideousness — and his subsequent attempt to kidnap Esmeralda, his rescue of Esmeralda from the gallows, his attempt to bring Phoebus to Esmeralda, and his final abandonment of the cathedral at the end of the novel. It is revealed in the story that the baby Quasimodo was left by the Gypsies in place of Esmeralda, whom they abducted.

- Esmeralda (born Agnes) is a beautiful young Gypsy street dancer who is naturally compassionate and kind. She is the center of the human drama within the story. A popular focus of the citizens' attentions, she experiences their changeable attitudes, being first adored as an entertainer, then hated as a witch, before being lauded again for her dramatic rescue by Quasimodo. She is loved by both Quasimodo and Claude Frollo, but falls deeply in love with Captain Phoebus, a handsome soldier who she believes will rightly protect her but who simply wants to seduce her. She is one of the few characters to show Quasimodo a moment of human kindness, as shown when she gives him water after the hunchback's flogging. She is eventually revealed to not actually be a gypsy, but was abducted by them and was replaced with the deformed Quasimodo.

- Claude Frollo, the novel's main antagonist, is the Archdeacon of Notre Dame. His dour attitude and his alchemical experiments have alienated him from the Parisians, who believe him a sorcerer. His parents having died of plague when he was a young man, he is without family save for Quasimodo, for whom he cares, and his spoiled brother Jehan, whom he attempts to reform towards a better life. Frollo's numerous sins include lechery, failed alchemy and other listed vices. His mad attraction to Esmeralda sets off a chain of events, including her attempted abduction, leading to Quasimodo's sentence to be lashed in the square, and Frollo almost murdering Phoebus in a jealous rage, leading to Esmeralda's execution.

- Jehan Frollo is Claude Frollo's 16-year-old over-indulged younger brother. He is a troublemaker and a student at the university. He is dependent on his brother for money, which he then proceeds to squander on alcohol. Quasimodo kills him during the attack on the cathedral. He briefly enters the cathedral by ascending one of the towers with a borrowed ladder, but Quasimodo sees him and throws him down to his death.

- Phoebus de Chateaupers is the Captain of the King's Archers. After he saves Esmeralda from abduction, she becomes infatuated with him, and he is intrigued by her. Already betrothed to the beautiful but spiteful Fleur-de-Lys, he wants to lie with Esmeralda nonetheless but is prevented when Frollo stabs him. Phoebus survives, but Esmeralda is taken to be the attempted assassin by all, including Phoebus himself. He is later married to Fleur-de-Lys and is miserable.

- Fleur-de-Lys de Gondelaurier is a beautiful and wealthy socialite engaged to Phoebus. Phoebus's attentions to Esmeralda make her insecure and jealous, and she and her friends respond by treating Esmeralda with contempt and spite. Fleur-de-Lys later neglects to inform Phoebus that Esmeralda has not been executed, which serves to deprive the pair of any further contact—though as Phoebus no longer loves Esmeralda by this time, this does not matter. The novel ends with their wedding.

- Pierre Gringoire is a struggling poet. He mistakenly finds his way into the "Court of Miracles", the domain of the Truands. In order to preserve the secrecy, Gringoire must either be killed by hanging, or marry a Gypsy. Although Esmeralda does not love him, and in fact believes him a coward rather than a true man — unlike Phoebus, he failed in his attempt to rescue her from Quasimodo — she takes pity on his plight and marries him. But, because she is already in love with Phoebus, much to his disappointment, she will not let him touch her.

- Sister Gudule, formerly named Paquette la Chantefleurie, is an anchoress, who lives in seclusion in an exposed cell in central Paris. She is tormented by the loss of her daughter Agnes, whom she believes to have been cannibalised by Gypsies as a baby, and devotes her life to mourning her. Her long-lost daughter turns out to be Esmeralda.

- Louis XI is the King of France. Appears briefly when he is brought the news of the rioting at Notre Dame. He orders his guard to kill the rioters, and also the "witch" Esmeralda.

- Tristan l'Hermite is a friend of King Louis XI. He leads the band that goes to capture Esmeralda.

- Henriet Cousin is the city executioner, who hangs Esmeralda.

- Florian Barbedienne is the judge who sentences Quasimodo to be tortured. He is also deaf.

- Jacques Charmolue is Frollo's friend in charge of torturing prisoners. He gets Esmeralda to falsely confess to killing Phoebus. He then has her imprisoned.

- Clopin Trouillefou is the King of Truands. He rallies the Court of Miracles to rescue Esmeralda from Notre Dame after the idea is suggested by Gringoire. He is eventually killed during the attack by the King's soldiers.

- Pierrat Torterue is the torturer who tortures Esmeralda after her interrogation. He hurts Esmeralda so badly she falsely confesses, sealing her own fate. He was also the official who administered the savage flogging awarded to Quasimodo by Barbedienne.

Major themes

The novel's original French title, Notre-Dame de Paris, indicates that the cathedral itself is the most significant aspect of the novel, both the main setting and the focus of the story's themes.[4] The building had fallen into disrepair at the time of writing, which was something Hugo felt strongly about. The book portrays the Romantic era as one of extremes in architecture, passion and religion. The theme of determinism (fate and destiny, as set up in the preface of the novel through the introduction of the word "ANANKH") is explored, as well as revolution and social strife.[5]

Architecture

Architecture is a major concern of Hugo's in Notre-Dame de Paris, not just as embodied in the cathedral itself, but as representing throughout Paris and the rest of Europe an artistic genre which, Hugo argued, was about to disappear with the arrival of the printing press. Claude Frollo's portentous phrase, ‘Ceci tuera cela’ ("This will kill that", as he looks from a printed book to the cathedral building), sums up this thesis, which is expounded on in Book V, chapter 2. Hugo writes that ‘quiconque naissait poète se faisait architecte’ ("whoever was born a poet became an architect"), arguing that while the written word was heavily censored and difficult to reproduce, architecture was extremely prominent and enjoyed considerable freedom.

Il existe à cette époque, pour la pensée écrite en pierre, un privilège tout-à-fait comparable à notre liberté actuelle de la presse. C'est la liberté de l'architecture.

There exists in this era, for thoughts written in stone, a privilege absolutely comparable to our current freedom of the press. It is the freedom of architecture.— Book V, Chapter 2

With the recent introduction of the printing press, it became possible to reproduce one's ideas much more easily on paper, and Hugo considered this period to represent the last flowering of architecture as a great artistic form. As with many of his books, Hugo was interested in a time which seemed to him to be on the cusp between two types of society.[6]

The major theme of the third book is that over time the cathedral has been repaired, but the repairs and additions have made the cathedral worse: "And who put the cold, white panes in the place of those windows" and "...who substituted for the ancient Gothic altar, splendidly encumbered with shrines and reliquaries, that heavy marble sarcophagus, with angels' heads and clouds" are a few examples of this. This chapter also discusses how, after repairs to the cathedral after the French Revolution, there was not a significant style in what was added. It seems as if the new architecture is actually now uglier and worse than it was before the repairing.

Literary significance and reception

Hugo introduced with this work the concept of the novel as Epic Theatre. A giant epic about the history of a whole people, incarnated in the figure of the great cathedral as witness and silent protagonist of that history. The whole idea of time and life as an ongoing, organic panorama centered on dozens of characters caught in the middle of that history. It is the first novel to have beggars as protagonists.

Notre Dame de Paris was the first work of fiction to encompass the whole of life, from the King of France to Paris sewer rats, in a manner later co-opted by Honoré de Balzac, Gustave Flaubert and many others, including Charles Dickens. The enormous popularity of the book in France spurred the nascent historical preservation movement in that country and strongly encouraged Gothic revival architecture. Ultimately it led to major renovations at Notre-Dame in the 19th century led by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. Much of the cathedral's present appearance is a result of this renovation.

Allusions and references

Allusions to actual history, geography and current science

In The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, Victor Hugo makes frequent reference to the architecture of the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris. He also mentions the invention of the printing press, when the bookmaker near the beginning of the work speaks of "the German pest."

In 2010, British archivist Adrian Glew discovered references to a real-life hunchback who was a foreman of a government sculpting studio in Paris in the 1820s who worked on post-Revolution restorations to the Cathedral.[7]

Allusions in other works

The name Quasimodo has become synonymous with "a courageous heart beneath a grotesque exterior."[8]

Drama adaptations

To date, all of the film and TV adaptations have strayed somewhat from the original plot, some going as far as to give it a happy ending, as in the classic 1939 film starring Charles Laughton as Quasimodo and Maureen O'Hara as Esmeralda (although Quasimodo loses her to Gringoire in this version). The 1956 French film, starring Anthony Quinn and Gina Lollobrigida, is one of the few versions to end almost exactly like the novel, although it changes other sections of the story. Unlike most adaptations, the 1996 Disney version has an ending that is inspired by an opera created by Hugo himself.

Films

- Esmeralda (1905 film)

- The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1911 film)

- The Darling of Paris

- Esmeralda (1922 film)

- The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923 film)

- The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939 film)

- The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1956 film)

- The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1986 film)

- The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1996 film)

- The Secret of the Hunchback (1996 film)

- The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1996 film) (Golden Films)

- The Hunchback (1997 film)

- Quasimodo d'El Paris

Television

- The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1966 miniseries)

- The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1977 miniseries)

- The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1982 film)

- The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1986 film)

- The Magical Adventures of Quasimodo

Theatre

- In 1977, an adaptation by Ken Hill was commissioned and staged by the National Theatre in London.

- In 2010, an adaptation by Pip Utton was staged at The Pleasance as part of the Edinburgh Fringe Festival.

- In 2010, an original adaptation by Myriad Theatre & Film was staged in London and then toured South England.

- In 2012, an adaptation by Belt Up Theatre was staged in Selby Abbey.

- In 2013, an adaptation by James Villafuerte was staged in Tanghalang Pasigueño Villa Teatro

- In 2013, an English adaptation of Der Glöckner von Notre Dame by The King's Academy Fine Arts Department was staged in The King's Academy Sports & Fine Arts Center

- In 2014, a musical adaptation of the novel using songs from the Disney film and Der Glöckner von Notre Dame opened at La Jolla Playhouse, produced in association with Paper Mill Playhouse by special arrangement with Disney Theatrical Group.[9]

Music

- The Hunchback of Notre Dame by Alec R. Costandinos and the Syncophonic Orchestra from 1977, a lush orchestral disco 28 minute epic re-telling the tale of Quasimodo and Esmeralda.

- The Hunchback of Notre Dame is a 1996 recording of music written by Styx singer Dennis DeYoung for his musical adaptation of the novel.

- The Hunchback of Notre Dame is the soundtrack to the 1996 Disney film, released by Walt Disney Records.

- The Hunchback of Notre Dame (Studio Cast Recording), a 2016 musical album based on Victor Hugo's novel and songs from the Disney film version.[10]

Musical theatre

- La Esmeralda, opera by Louise Bertin (1836), libretto by Victor Hugo.

- Esmeralda, opera by Alexander Dargomyzhsky (1847) based on the Victor Hugo novel.

- Notre-Dame of Paris, opera by William Henry Fry (1864) with libretto by his brother Joseph Reese Fry based on the Victor Hugo novel. First performance: Academy of Music, Philadelphia, 4 May 1864, conducted by Theodore Thomas.

- Esmeralda, opera by Arthur Goring Thomas (1883), also based on the same Victor Hugo novel.

- Notre Dame, romantic Opera in two acts by Franz Schmidt, text after Victor Hugo by Schmidt and Leopold Wilk; composed: 1902-4, 1st perf.: Vienna 1914.

- The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1993), an Off Broadway musical with music by Byron Janis, lyrics by Hal Hackady and book by Anthony Scully.[11]

- The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1993), a dramatic sung-through musical with book and lyrics by Gary Sullivan and music by John Trent Wallace.[12] After a production at the Mermaid Theatre in London it was published by Samuel French Ltd in 1997 and has received several UK productions as well as productions in New Zealand and Australia. In 2010 it was re-written as a conventional musical, with the new title Notre Dame.[13]

- El Jorobado de París (1993), an Argentinian sung-through musical with book and lyrics by Pepe Cibrián Campoy and music by Ángel Mahler. Revised versions opened in 1995, 2006 and 2013.

- In 1998, Notre-Dame de Paris opened in Paris and became an instant success. It is considered the most successful adaptation of any novel except for "The Phantom of the Opera" and "Les Misérables." It was also adapted for the stage by Nicholas DeBaubien.[14]

- From 1999 to 2002, the Disney film was adapted into a darker, more Gothic musical production called Der Glöckner von Notre Dame (translated in English as The Bellringer of Notre Dame), re-written and directed by James Lapine and produced by the Disney theatrical branch, in Berlin. A cast recording was also recorded in German.[15] There has been discussion of an American revival of the musical.

- A rock musical version was released in Seattle, Washington in 1998 titled "Hunchback" with music and script by C. Rainey Lewis.[16]

- A musical version, scored by Dennis DeYoung, opened in Chicago at the Bailiwick Repertory in the summer of 2008.[17]

- A re-adaptation of the piece entitled "Our Lady of Paris" with music and lyrics by David Levinson and book by Stacey Weingarten was produced in a reading format in Manhattan. It re-sets the action to 1954 at the beginning of the French Algerian conflict. Directed by Donna Drake, Music Directed by Mark Hartman, starring Michael Barr, Matt Doyle, Adam Halpin, Sevan Greene, Nadine Malouf, Megan Reinking and Price Waldman. After the first reading the piece underwent revisions; a second reading was produced in January 2011 under the musical's new title, Les Enfants de Paris.

- Notre-Dame de Paris is an operatic melodrama by Zigmars Liepiņš based on the novel.

Ballet

- La Esmeralda (1844) - choreography by Jules Perrot, music by Cesare Pugni. First performed at Her Majesty's Theatre in London. The ballet has a long performance history in Russia via the revivals of the choreographer Marius Petipa in St. Petersburg throughout the late 19th century.

- Gudule’s Daughter, or Esmiralda (1902) – choreography by Alexander Alexeyevich Gorsky, music by Antoine Simon

- Notre-Dame de Paris (1965) – choreography by Roland Petit, first performed by the Paris Opera Ballet.

- The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1998) – choreography and direction by Michael Pink and original music score by Philip Feeney; currently in the repertoire of Milwaukee Ballet, Boston Ballet, Royal New Zealand Ballet, Atlanta Ballet and Colorado Ballet.

- Ringaren i Notre Dame (The Bellringer of Notre Dame; 2009) – choreography by Pär Isberg and original music score by Stefan Nilsson, first performed on Friday, April 3, by the Royal Swedish Ballet.

Radio

The book was twice adapted and broadcast by BBC Radio 4 as its Classic Serial:

- in 5 parts from 6 January to 3 February 1989, with Jack Klaff as Quasimodo

- in 2 parts on 30 November and 7 December 2008, with deaf actor David Bower playing Quasimodo.

Video games

- Hunchback, a 1983 arcade video game an arcade game developed by Century Electronics, starring Quasimodo.

Translation history

The Hunchback of Notre-Dame has been translated into English many times. Translations are often reprinted in various imprints. Some translations have been revised over time.

- 1833. Translated by Frederic Shoberl as The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Later revisions.

- 1833. Translated by William Hazlitt as Notre Dame: A Tale of the Ancien Regime. Later revisions.

- 1888. Translated by Isabel F. Hapgood as Notre-Dame de Paris.

- 1895. Translated by M.W. Artois et al., part of the 28-vol The Novels of Victor Hugo, re-printed in the 20th century under other titles.

- 1956. Translated by Lowell Bair, for Bantam Books and included in Bantam Classics

- 1964. Translated by Walter J. Cobb. In multiple editions, see for example Signet Classics ISBN 0-451-52788-7

- 1978. Translated by John Sturrock. In multiple editions, see for example Penguin Classics ISBN 0-14-044353-3

- 1993. Translated by Alban J. Krailsheimer as Notre-Dame de Paris. See Oxford World's Classics ISBN 978-0-19-955580-2

- 2002. Revised translation by Catherine Liu of an anonymous 19th century translation. See Modern Library Classics ISBN 0-679-64257-9

- 2006. Translated by Mary Grace M. Ada as Notre-Dame de Paris. See Oxford World's Classics ISBN 978-0-19-955580-2

References

Notes

- ↑ hubpages.com/entertainment/quasimodo

- ↑ fr:Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris

- ↑ fr:Notre-Dame de Paris (roman)#cite note-21

- ↑ Zaretsky, Rob. "Victor Hugo and Architecture", Engines of our Ingenuity. Accessed 2 June 2016.

- ↑ "Sparknotes.com". Sparknotes.com. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ↑ "Online-literature.com". Online-literature.com. 26 January 2007. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ↑ "Real-life Quasimodo uncovered in Tate archives", Roya Nikkhah, The Daily Telegraph, 15 August 2010

- ↑ Webber, Elizabeth; Mike Feinsilber (1999). Merriam-Webster's Dictionary of Allusions. Merriam-Webster. p. 592. ISBN 0-87779-628-9.

- ↑ "Know Before You Go: The Hunchback of Notre Dame" (PDF). http://www.lajollaplayhouse.org/. Retrieved 21 October 2014. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ BWW News Desk (22 January 2016). "Sanctuary! THE HUNCHBACK OF NOTRE DAME Cast Album Released Today". BroadwayWorld.com.

- ↑ "The Hunchback of Notre Dame". Lortel.org. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ↑ "Johntrentwallace.com". Johntrentwallace.com. 5 December 2010. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ↑ "Notre-dame.co.uk". Notre-dame.co.uk. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ↑ Mainstage 1997 – Nicholas De Beabien's The Hunchback of Notre Dame, sacred.fools.org

- ↑ Collins, Suzanne. "Amazon.com". Amazon.com. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ↑ "Hunchback". Hunchback. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ↑ "Hunchback of Notre Dame Musical By Styx Front-Man to Play Chicago's Bailiwick". Playbill. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

Bibliography

- Rebello, Stephen. The Art of The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1996 ed.). Hyperion. ISBN 0-7868-6208-4.

- Pascal Tonazzi, Florilège de Notre-Dame de Paris (anthologie), Editions Arléa, Paris, 2007, ISBN 2-86959-795-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Notre-Dame de Paris (Victor Hugo). |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Hunchback of Notre-Dame |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- The Hunchback of Notre Dame at Internet Archive and Google Books, multiple English translations (scanned books original editions color illustrated)

- Notre-Dame De Paris at Project Gutenberg, 1888 English translation by Isabel Florence Hapgood (plain text and HTML)

-

The Hunchback of Notre Dame public domain audiobook at LibriVox, 1888 English translation by Isabel Florence Hapgood and French available

The Hunchback of Notre Dame public domain audiobook at LibriVox, 1888 English translation by Isabel Florence Hapgood and French available - Notre Dame de Paris Harvard Classics

- Notre-Dame de Paris at Wikisource (HTML) (French)