The Other

| The Other | |

|---|---|

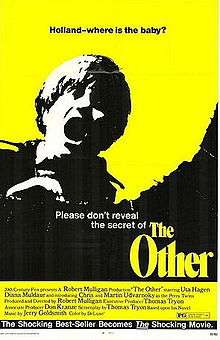

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Robert Mulligan |

| Produced by |

Tom Tryon Robert Mulligan |

| Written by | Tom Tryon (also novel) |

| Starring |

Uta Hagen Diana Muldaur Chris Udvarnoky Martin Udvarnoky |

| Music by | Jerry Goldsmith |

| Cinematography | Robert L. Surtees |

| Edited by |

Folmar Blangsted O. Nicholas Brown |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release dates | May 26, 1972 |

Running time | 108 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2,250,000[1] |

| Box office | $3.5 million (US/ Canada)[2] |

The Other is a 1972 psychological thriller film directed by Robert Mulligan,[3] adapted for film by Tom Tryon from his novel of the same name. It stars Uta Hagen, Diana Muldaur, and Chris and Martin Udvarnoky.

Plot

It's a seemingly idyllic summer in 1935, and identical twins Niles and Holland Perry play on the bucolic family farm. Holland is an amoral mischief maker while Niles is more sympathetic. Niles carries a tobacco tin with him containing several secret trinkets, including the Perry family ring, which had been handed down to Holland, the older twin. Their obnoxious cousin Russell finds them in the apple cellar below the barn—a place they are not supposed to play—and sees the contents of the tobacco tin. Russell states that the ring was supposed to be buried, and promises to "tell on" Niles to his father, Niles' Uncle George. Uncle George padlocks the door to the cellar, but there is another stairway inside the barn, giving them access.

The twins' mother is a frail recluse, physically weak and emotionally damaged. Grandmother Ada, a Russian emigrant, dotes on Niles, and has taught him a psychic ability to project himself outside of his body, for example in a bird; this ability she calls "the great game."

Several tragedies befall the family and neighborhood, to people who have caused trouble for the boys, and it appears Holland may be responsible. Russell is killed before he can reveal that Niles has the heirloom ring. Neighbor Mrs. Rowe, who had complained because Holland broke a jar of her preserves, has a fatal heart attack. The twins' mother finds Niles' tobacco tin, containing a severed finger. That night, she demands that Niles tell her how he has possession of the ring and he says Holland gave it to him. She is shocked; a struggle ensues and she falls down the stairs and is rendered partially paralyzed.

Ada discovers Mrs. Rowe's dead body, and finds Holland's harmonica at the scene. She seeks out Niles and locates him in church, where he is transfixed by the image of "The Angel of a Better Day," which Ada had described to Niles as a comforting conveyor of the soul to heaven. Ada confronts Niles, and he identifies Holland as the culprit. Ada demands that he face the truth: Holland has been dead since their birthday in March, when he fell down the well trying to drown a cat. He was thought to have been buried with his father's ring. Niles relives the memory of how he acquired the ring: he opened Holland's coffin and Holland spoke to him, insisting that he cut his finger off and take the ring. Niles kept both the ring and the severed finger.

Niles appears to have developed a fascination for the recent Lindbergh kidnapping tragedy. The newborn baby of Torrie, Niles' older sister, is kidnapped, an ugly doll left in the baby's place, somewhat like the Lindbergh case. Ada discovers Niles shouting for Holland to tell where the baby is. Ada must now face the realization that her beloved Niles is disturbed and criminally insane. The baby is found drowned in the gardener's open wine cask. Ada hears Niles in the apple cellar, whispering with Holland. She starts a fire in the cellar, and Niles looks up as she is diving toward him, mentally seeing an image of "The Angel of a Better Day." He smiles.

As autumn begins, the ruins of the barn are being cleared. The camera focuses on a padlock that has been cut open with a hacksaw. It is the lock that Uncle George had placed on the door to the cellar. We remember hearing the sound of a hacksaw in a previous scene, when Ada shouted into the barn for Niles. Niles is alive and well, watching the clean-up from the house. His mother is a catatonic invalid, Ada has died in the barn fire, and no one knows Niles' terrible secret.

Endings

When the film aired on CBS in the 1970s, a voice-over at the end of the film has Niles speaking to Holland: "Holland, the game's over. We can't play the game anymore. But when the sheriff comes, I'll ask him if we can play it in our new home." The voice-over truncates a line by the maid, Winnie, who in the theatrical cut says, "Niles, wash up now — time for lunch," whereas in the voice-over version she is cut off after merely "Niles, wash up now." The voice-over is not on the home video releases nor has it appeared on any recent television airing.

Cast

- Chris Udvarnoky – Niles Perry

- Martin Udvarnoky – Holland Perry

- Uta Hagen – Ada

- Diana Muldaur – Alexandra

- Norma Connolly – Aunt Vee

- Victor French – Mr. Angelini

- Loretta Leversee – Winnie

- Lou Frizzell – Uncle George

- Clarence Crow – Russell

- John Ritter – Rider

- Jenny Sullivan – Torrie

- Portia Nelson – Mrs. Rowe

- Jack Collins – Mr. Pretty

Production

The film was shot entirely on location in Murphys, California and Angels Camp, California. Director Robert Mulligan had hoped to shoot the film on location in Connecticut, where it takes place, but because it was autumn when the film entered production (and therefore the color of the leaves would not reflect the height of summer, when the story takes place) this idea was dropped.

Mulligan described his intentions with the film: “I want to put the audience into the body of the boy with this shot and to make the experience of the film, from beginning to end, a totally subjective one.” Of the character of Niles, he commented, “If Niles could have life just the way he wanted it, his world would contain only Ada, Holland, and himself—preferably only Holland and himself." Of the character of Ada, he commented, “She was the heart of the house. She has a primitive sense of imagination and drama, which is the greatest thing an adult can give a child… Her only failing is that she has a maternal love so strong that it blinds her to what is happening. Though she enriches and turns on the child’s imagination, her gift is used in a destructive way by the child.”[4]

This would be the only movie appearance by the twins Chris and Martin Udvarnoky, the featured stars. Mulligan never shows the brothers in frame together. They are always separated by a camera pan, or an editing cut.

John Ritter would make one of his earliest appearances in the film, as the boys' brother-in-law, Rider Gannon. Rider's young wife and the twins' sister, Torrie, is played by Jenny Sullivan.

Goldsmith's compositions for the film can be heard in a 22-minute suite found on the soundtrack album of The Mephisto Waltz. This CD was released 25 years after the release of the film. According to the liner notes of the soundtrack, over half of Goldsmith's music was removed during the film's post production. It does not specify whether this was the result of deleted footage or a decision affecting the music only.

Chris Udvarnoky eventually became an emergency medical technician. He died in Elizabeth, New Jersey on October 25, 2010, at the age of 49. Coincidentally, this was also the same day that the film made its premiere showing on Turner Classic Movies. Martin Udvarnoky works as a massage therapist in Summit, New Jersey.

Reception

The film experienced a quiet theatrical run, but it had regular television airings in the late '70s. Among the film's admirers was Roger Ebert, who wrote in his review, "[The film] has been criticized in some quarters because Mulligan made it too beautiful, they say, and too nostalgic. Not at all. His colors are rich and deep and dark, chocolatey browns and bloody reds; they aren't beautiful but perverse and menacing. And the farm isn't seen with a warm nostalgia, but with a remembrance that it is haunted."[5] After Chris Udvarnoky's death on October 25, 2010,[6] Ebert paid tribute to Udvarnoky on his Twitter page.[7]

Tom Tryon, however, was disappointed with the film, despite having written the screenplay himself. When asked about the film in a 1977 interview, Tryon recalled, "Oh, no. That broke my heart. Jesus. That was very sad... That picture was ruined in the cutting and the casting. The boys were good; Uta was good; the other parts, I think, were carelessly cast in some instances--not all, but in some instances. And, God knows, it was badly cut and faultily directed. Perhaps the whole thing was the rotten screenplay, I don't know. But I think it was a good screenplay."

In the same interview, Tryon also hinted that he had been initially considered to direct the film before Mulligan was hired for the job: "It was all step-by-step up to the point of whether I was going to become a director or not. The picture got done mainly because the director who did it wanted to do that property, and he was a known director; he was a known commodity."[8]

For his part, director Mulligan admitted that in post-production, “I cut a lot in The Other from long, open shots to tight, constricting close-ups."[9]

See also

References

- ↑ Solomon, Aubrey. Twentieth Century Fox: A Corporate and Financial History (The Scarecrow Filmmakers Series). Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0-8108-4244-1. p256

- ↑ Solomon p 232. Please note figures are rentals not total gross.

- ↑ "The Other". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved April 10, 2016.

- ↑ http://www.thefilmjournal.com/issue11/adrobertmulligan.html

- ↑ "The Other". Chicago Sun-Times.

- ↑ Obituaries & Guestbooks from The Star-Ledger

- ↑ "Ebertchicago". Twitter.

- ↑ ^ a b c Dahlin 1977, p. 263

- ↑ http://www.thefilmjournal.com/issue11/adrobertmulligan.html

Bibliography

- Dahlin, Robert (1977). Conversations With Writers. Detroit, Michigan: Gale Research Company. ISBN 0-8103-0943-2.

External links

- The Other at the Internet Movie Database

- The Other at AllMovie

- Roger Ebert's review of the movie

- Review at Scifilm.org

- The Other at Rotten Tomatoes