Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde

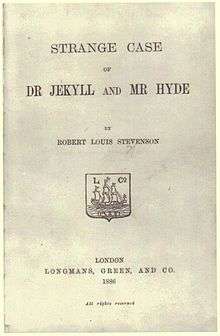

Title page of the first London edition (1886) | |

| Author | Robert Louis Stevenson |

|---|---|

| Original title | Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Series | None |

| Genre |

Drama Horror Mystery Thriller Gothic Science fiction |

| Publisher | Longmans, Green & Co. |

Publication date | 5 January 1886 |

| ISBN | 978-0-553-21277-8 |

Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde is a novella by the Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson first published in 1886. The work is commonly known today as The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, or simply Jekyll & Hyde.[1] It is about a London lawyer named Gabriel John Utterson who investigates strange occurrences between his old friend, Dr. Henry Jekyll,[2][3] and the evil Edward Hyde. The novella's impact is such that it has become a part of the language, with the very phrase "Jekyll and Hyde" coming to mean a person who is vastly different in moral character from one situation to the next.[4][5]

There have been many audio recordings of the novella, with some of the more famous readers including Tom Baker, Roger Rees, Christopher Lee, Anthony Quayle, Martin Jarvis, Tim Pigott-Smith, John Hurt, Ian Holm and Gene Lockhart.

Inspiration and writing

Stevenson had long been intrigued by the idea of how personalities can affect a human and how to incorporate the interplay of good and evil into a story. While still a teenager, he developed a script for a play about Deacon Brodie, which he later reworked with the help of W. E. Henley and which was produced for the first time in 1882.[6] In early 1884 he wrote the short story "Markheim", which he revised in 1884 for publication in a Christmas annual. According to his essay, "A Chapter on Dreams" (Scribner's Jan. 1888), he racked his brains for an idea for a story and had a dream, and upon wakening had the intuition for two or three scenes that would appear in the story Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Biographer Graham Balfour quoted Stevenson's wife Fanny Stevenson:

In the small hours of one morning,[...]I was awakened by cries of horror from Louis. Thinking he had a nightmare, I awakened him. He said angrily: "Why did you wake me? I was dreaming a fine bogey tale." I had awakened him at the first transformation scene.[7]

Lloyd Osbourne, Stevenson's stepson, wrote: "I don't believe that there was ever such a literary feat before as the writing of Dr Jekyll. I remember the first disease of the world though it were yesterday. Louis came downstairs in a fever; read nearly half the book aloud; and then, while we were still gasping, he was away again, and busy writing. I doubt if the first draft took so long as three days."[7]

Inspiration may also have come from the writer’s friendship with French doctor Eugene Chantrelle, who was convicted and executed for the murder of his wife in Edinburgh in May 1878.[8] Chantrelle, who had appeared to lead a normal life in the city, poisoned his wife with opium. According to author Jeremy Hodges,[9] Stevenson was present throughout the trial and as "the evidence unfolded he found himself, like Dr Jekyll, ‘aghast before the acts of Edward Hyde’.” Moreover, it was believed that the doctor had committed other murders both in France and Britain by poisoning his victims at supper parties with a "favourite dish of toasted cheese and opium".[10]

Louis Vivet, a mental patient who was suffering from Multiple Personality, caught Frederic W. H. Myers's attention and he wrote to Stevenson after the story was published. Stevenson was polite in his response, but rejected that reading. As was customary, Mrs Stevenson would read the draft and offer her criticisms in the margins. Robert Stevenson was confined to bed at the time from a haemorrhage. Therefore, she left her comments with the manuscript and Robert in the toilet. She said that in effect the story was really an allegory, but Robert was writing it as a story. After a while Robert called her back into the bedroom and pointed to a pile of ashes: he had burnt the manuscript in fear that he would try to salvage it, and in the process forced himself to start again from nothing, writing an allegorical story as she had suggested. Scholars debate whether he really burnt his manuscript; there is no direct factual evidence for the burning, but it remains an integral part of the history of the novella.[11]

Stevenson re-wrote the story in three to six days. A number of later biographers have alleged that Stevenson was on drugs during the frantic re-write; for example, William Gray's revisionist history A Literary Life (2004) said he used cocaine, while other biographers said he used ergot.[12] However, the standard history, according to the accounts of his wife and son (and himself), says he was bed-ridden and sick while writing it. According to Osbourne, "The mere physical feat was tremendous and, instead of harming him, it roused and cheered him inexpressibly". He continued to refine the work for four to six weeks after the initial re-write. The novella was written in the southern English sea side town of Bournemouth, where Stevenson had moved due to ill health, to benefit from its sea air and warmer southern climate.

The name Jekyll was borrowed from Reverend Walter Jekyll, a friend of Stevenson and younger brother of horticulturalist and landscape designer Gertrude Jekyll.[13]

Plot

Gabriel John Utterson, a lawyer, is on his weekly walk with his cousin, Richard Enfield. They reach a door leading into a rather large house, and Enfield tells Utterson of an encounter he had some months ago between a man and a young girl. The man, a sinister figure named Edward Hyde, and the young girl accidentally bump into one another, but Hyde proceeds to trample her. Enfield chases after Hyde and forces Hyde to pay £100 to avoid a scandal for his behaviour. Hyde leads them to this door, which he enters and re-emerges with £10 in gold and a cheque for the rest. The cheque is signed by a reputable gentleman, later revealed to be Dr. Henry Jekyll, one of Utterson's clients and old friends.) Jekyll had recently so drafted his will as to make Hyde the sole beneficiary in case of his death or—much to Utterson's discomfort—his disappearance for more than three months. This development concerns and disturbs Utterson, who tries to seek out Hyde, fearing that Hyde is blackmailing Jekyll. When he finally meets Hyde, the latter's ugliness, as if deformed, amazes Utterson. Although Utterson cannot say exactly how or why, Hyde provokes an instinctive feeling of revulsion in him. Much to Utterson's surprise, Hyde willingly offers Utterson his address. After one of Jekyll's dinner parties, Utterson stays behind to discuss the matter of Hyde with Jekyll. This causes Jekyll to turn pale, but Jekyll assures Utterson that everything involving Hyde is in order and that Hyde should be left alone.

A year passes uneventfully. One night in late October, a servant girl witnesses Hyde beat a man to death with a heavy cane. The victim was MP Sir Danvers Carew, another of Utterson's clients, who was carrying a letter addressed to Utterson when he was killed. The police contact Utterson, and he leads the officers to Hyde's apartment. When they arrive at the apartment, the murderer has vanished, but they find half of the cane left behind a door. Utterson recognizes the cane as one which he had given to Jekyll. Shortly thereafter, Utterson again visits Jekyll, who now claims to have ended all relations with Hyde. Jekyll shows Utterson a note, allegedly written to Jekyll by Hyde, apologising for the trouble that he has caused him and saying goodbye. However, Utterson's clerk, Mr. Guest, points out that Hyde's handwriting bears a remarkable similarity to Jekyll's own, leading Utterson to conclude that Jekyll had forged the note to protect Hyde.

For two months, Jekyll reverts to his former friendly and sociable manner, as if a weight has been lifted from his shoulders. But in early January, Jekyll suddenly starts refusing visitors, and Dr. Hastie Lanyon, a mutual acquaintance of Jekyll and Utterson, dies suddenly of shock after receiving information relating to Jekyll. Before his death, Lanyon gives Utterson a letter, with instructions that he should only open it after Jekyll's death or disappearance. In late February, Utterson goes out walking with Enfield, and they see Jekyll at a window of his laboratory. The three men start conversing, but a look of horror suddenly comes over Jekyll's face, and he slams the window and disappears. Soon afterwards, in early March, Jekyll's butler, Mr. Poole, visits Utterson in a state of desperation and explains that Jekyll has secluded himself in his laboratory for several weeks. Utterson and Poole travel to Jekyll's house, where they find the servants huddled together in fear. They go to the laboratory where they hear the voice of the person inside is not Jekyll's voice and the footsteps are light instead of the heavy footsteps of the doctor. The two break into Jekyll's laboratory, where they find the body of Hyde wearing Jekyll's clothes and apparently dead from suicide. They find also a letter from Jekyll to Utterson promising to explain the entire mystery, as well as a new will which disinherits Edward Hyde and names Gabriel John Utterson sole residuary legatee. Utterson takes the document back to his home, where he first reads Lanyon's letter and then Jekyll's. Lanyon's letter reveals his deterioration and eventual death resulting from the shock of seeing Hyde drinking a serum (potion or "draught") and, as a result of doing so, turning into Dr. Jekyll. The second letter explains that Jekyll, having previously indulged in unstated vices (and with it the fear that discovery would lead to his losing his social position) found a way to transform himself and thereby indulge his vices without fear of detection. But Jekyll's transformed personality, Hyde, was effectively a sociopath—evil, self-indulgent, and utterly uncaring to anyone but himself. Initially, Jekyll was able to control the transformations, but one night in August, he became Hyde involuntarily in his sleep.

At this point, Jekyll resolved to cease becoming Hyde. On the October night of Sir Danvers Carew's murder, however, the urge gripped him too strongly, and he took the potion. Hyde, furious at having been caged for so long, rushed out and killed Sir Danvers. Horrified, Jekyll tried more adamantly to stop the transformations, and for a time he proved successful by engaging in philanthropic work. One day in early January, while at a park, he considered how good a person he had become as a result of his deeds in comparison to others, believing himself redeemed. However, before he completed his line of thought, he suddenly transformed once again into Hyde. This was the first time that an involuntary metamorphosis had happened while awake. Far from the chemicals in his laboratory and now hunted by the police as a murderer, Hyde needed help to avoid being caught. He wrote to Lanyon (in Jekyll's hand), asking his friend to retrieve the contents of a cabinet in his laboratory and to meet him at midnight at Lanyon's home in Cavendish Square. In Lanyon's presence, Hyde mixed the chemicals, drank the draught, and transformed back into Jekyll. The shock of the sight, for which Lanyon condemned Jekyll and declared the two former friends irredeemably estranged, instigated Lanyon's deterioration and death. Meanwhile, Jekyll returned to his home, only to find himself ever more helpless and trapped as the involuntary transformations increased in frequency and necessitated ever larger doses of the draught to reverse them. It was the onset of one of these transformations that caused Jekyll to slam his laboratory window shut in the middle of his conversation with Enfield and Utterson.

Eventually, one of the chemicals from which Jekyll had been preparing the draught ran low, and subsequent batches prepared by Jekyll from renewed stocks failed to produce the transformation. Jekyll speculated that the one essential ingredient that made the original draught work must have been contaminated. His supplies of the draught running low, Jekyll decided to write his "confession". Jekyll wrote that even as he composed his letter, he knew that he would soon become Hyde permanently, having used the last of this salt, and he wondered if Hyde would face execution for his crimes or choose to kill himself. Jekyll noted that, in either case, the end of his letter marked the end of the life of Dr. Jekyll. He ended the letter by saying, "I bring the life of that unhappy Henry Jekyll to an end." With these words, both the document and the novella come to a close.

Characters

Dr. Henry Jekyll/Mr. Edward Hyde

Dr. Jekyll is a "large, well-made, smooth-faced man of fifty with something of a slyish cast",[14] who occasionally feels he is battling between the good and evil within himself, thus leading to the struggle between his dual personalities of Henry Jekyll and Edward Hyde. He has spent a great part of his life trying to repress evil urges that were not fitting for a man of his stature. He creates a serum, or potion, in an attempt to mask this hidden evil within his personality. However, in doing so, Jekyll transforms into the smaller, younger, cruel, remorseless, evil Hyde. Jekyll has many friends and has an amiable personality, but as Hyde, he becomes mysterious and violent. As time goes by, Hyde grows in power. After taking the potion repeatedly, he no longer relies upon it to unleash his inner demon, i.e., his alter ego. Eventually, Hyde grows so strong that Jekyll becomes reliant on the potion to remain conscious.

Gabriel John Utterson

Gabriel John Utterson, a lawyer and loyal friend of Jekyll's (and Lanyon's), is the character the narrator focuses on, and follows in Utterson's quest to discover the identity of Hyde. Utterson is a measured, and at all times emotionless, bachelor – who nonetheless seems believable, trustworthy, tolerant of the faults of others, and indeed genuinely likeable. Utterson has been close friends with Lanyon and Dr. Jekyll. However, Utterson is not immune to guilt, as, while he is quick to investigate and judge the faults of others even for the benefit of his friends, Stevenson states that "he was humbled to the dust by the many ill things he had done". Whatever these "ill things" may be, he does not partake in gossip or other views of the upper class out of respect for his fellow man. Often the last remaining friend of the down-falling, he finds an interest in others' downfalls, which creates a spark of interest not only in Jekyll but also regarding Hyde. He comes to the conclusion that human downfall results from indulging oneself in topics of interest. As a result of this line of reasoning, he lives life as a recluse and "dampens his taste for the finer items of life". Utterson concludes that Jekyll lives life as he wishes by enjoying his occupation. Utterson is a good friend to Henry Jekyll.

Richard Enfield

Richard Enfield is Utterson's distant relative and is a well known "man about town", suggesting a certain sexual licentiousness. Evidence to support this is that he first sees Hyde at about three in the morning in an episode that is well documented as Hyde is running over a little girl. He is the person who mentions to Utterson the actual personality of Jekyll's heir, Hyde. Enfield witnessed Hyde running over a little girl in the street recklessly, and the group of witnesses, with the girl's parents and other residents, force Hyde into writing a cheque for the girl's family. Enfield discovers that Jekyll signed the cheque, which is genuine. He says that Hyde is disgusting looking but finds himself stumped when asked to describe the man.

Dr. Hastie Lanyon

A longtime friend of Jekyll's, Hastie Lanyon disagrees with his "scientific" concepts, which Lanyon describes as "...too fanciful". He is the first person to discover Hyde's true identity (Hyde transforms himself back into Jekyll in Lanyon's presence). Lanyon helps Utterson solve the case, when he describes the letter given to him by Jekyll, and his thoughts and reactions to the transformation. When Lanyon witnesses the transformation process (and subsequently hears Jekyll's private confession, made to him alone), Lanyon becomes critically ill and later dies of shock.

Mr. Poole

Poole is Jekyll's butler who has lived with him for many years. Upon noticing the reclusiveness and changes of his master, Poole goes to Utterson with the fear that his master has been murdered and his murderer, Mr Hyde, is residing in the chambers. Poole serves Jekyll faithfully, and attempts to do a good job and be loyal to his master. Yet events finally drive him into joining forces with Utterson to find the truth.

Inspector Newcomen

Utterson joins this Scotland Yard inspector after the murder of Sir Danvers Carew. They explore Hyde's loft in Soho and discover evidence of his depraved life. He is driven by professional ambition and sees the murder of Sir Danvers Carew as a way to further his career.

Sir Danvers Carew, MP

A kind, white-haired old man and an important Member of Parliament. The maid claims that Hyde, in a murderous rage, killed Carew in the streets of London on the night of 18 October (sometime between 11 pm and 2 am by the testimony of the maid). At the time of his death, Carew is 70 years old and is carrying on his person a letter addressed to Utterson. As a result, the police subsequently interview Utterson with regard to the murder.

Maid

A maid, whose employer Hyde had once visited, is the only person who claims to have witnessed the murder of Sir Danvers Carew. She states that she saw that Mr. Hyde murdered Carew with Jekyll's cane. Having fainted after seeing what happened, she then wakes up and rushes to the police, thus initiating the murder case of Sir Danvers Carew.

Analysis

Literary genres which critics have applied as a framework for interpreting the novel include religious allegory, fable, detective story, sensation fiction, Doppelgänger literature, Scottish devil tales and gothic novel.

Themes

Dualities

The novella is frequently interpreted as an examination of the duality of human nature, usually expressed as an inner struggle between good and evil, with variations such as human versus animal, civlization versus barbarism sometimes substituted, the main thrust being that of an essential inner struggle between the one and other, and that the failure to accept this tension results in evil, or barbarity, or animal violence, being projected onto others.[15] In Freudian theory the thoughts and desires banished to the unconscious mind motivate the behaviour of the conscious mind. If someone banishes all evil to the unconscious mind in an attempt to be wholly and completely good, it can result in the development of a Mr Hyde-type aspect to that person's character.[15] This failure to accept the tension of duality is related to Christian theology, where Satan's fall from Heaven is due to his refusal to accept that he is a created being (that he has a dual nature) and is not God.[15] This idea is suggested when Hyde says to Lanyon, shortly before drinking the famous potion – "...and your sight shall be blasted by a prodigy to stagger the unbelief of Satan." This is because in Christianity, pride (to consider oneself as without sin or without evil) is the greatest sin, as it is the precursor to evil itself.[15]

In his discussion of the novel, Vladimir Nabokov argues that the "good versus evil" view of the novel is misleading, as Jekyll himself is not, by Victorian standards, a morally good person.[16]

Public vs private

The work is commonly associated today with the Victorian concern over the public and private division, the individual's sense of playing a part and the class division of London [4] In this respect, the novella has also been noted as "one of the best guidebooks of the Victorian era" because of its piercing description of the fundamental dichotomy of the 19th century "outward respectability and inward lust," as this period had a tendency for social hypocrisy.[17]

Scottish nationalism vs union with Britain

Another common interpretation sees the novella's duality as representative of Scotland and the Scottish character. In this reading the duality represents the national and linguistic dualities inherent in Scotland's relationship with the wider Britain and the English language, respectively, and also the repressive effects of the Church of Scotland on the Scottish character.[11] A further parallel is also drawn with the city of Edinburgh itself, Stevenson's birthplace, which consists of two distinct parts: the old medieval section historically inhabited by the city's poor, where the dark crowded slums were rife with all types of crime, and the modern Georgian area of wide spacious streets representing respectability.[11][18][19]

Reception

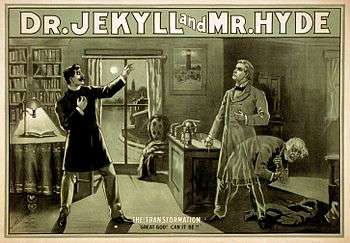

Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde was an immediate success and is one of Stevenson's best-selling works. Stage adaptations began in Boston and London and soon moved all across England and then towards his home Scotland.[4]

Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde was initially sold as a paperback for one shilling in the UK and one dollar in the U.S.. The American publisher issued the book on 5 January 1886, four days before the first appearance of the UK edition issued by Longmans; Scribner's published 3000 copies, only 1250 of them bound in cloth. Initially stores would not stock it until a review appeared in The Times, on 25 January 1886, giving it a favourable reception. Within the next six months, close to forty thousand copies were sold. As Stevenson's biographer, Graham Balfour, wrote in 1901, the book's success was probably due rather to the "moral instincts of the public" than to any conscious perception of the merits of its art. It was read by those who never read fiction and quoted in pulpit sermons and in religious papers.[20] By 1901 it was estimated to have sold over 250,000 copies in the United States.[21]

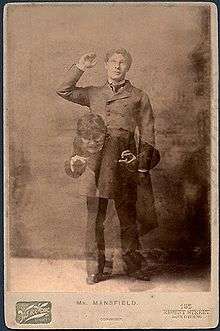

Adaptations

There have been numerous adaptations of the novella including over 120 stage and film versions alone.[22]

Illustrated Versions

S.g. Hulme Beaman illustrated a 1930s editon[23]

References

- ↑ Stevenson published the book as Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (without "The"), for reasons unknown, but it has been supposed to increase the "strangeness" of the case (Richard Dury (2005)). Later publishers added "The" to make it grammatically correct, but it was not the author's original intent. The story is often known today simply as Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde or even Jekyll and Hyde.

- ↑ /ˈdʒiːkəl/ is the Scots pronunciation of the name, but /ˈdʒɛkəl/ is the accepted general pronunciation.

- ↑ "Noted - Futility Closet". Futility Closet.

- 1 2 3 Saposnik, Irving S. "The Anatomy of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde." Studies in English Literature, 1500–1900 11.4, Nineteenth Century (1971): pp. 715–731.

- ↑ "Jekyll and Hyde definition | Dictionary.com". Dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved 28 May 2009.

- ↑ Swearingen, Roger G. The Prose Writings of Robert Louis Stevenson. London: Macmillan, 1980. (ISBN) p. 37.

- 1 2 Balfour, Graham (1912). The Life of Robert Louis Stevenson. II. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 15–6. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ↑ Chantrelle, Eugène Marie; Smith, Alexander Duncan. Trial of Eugène Marie Chantrelle. Toronto, Canada Law Book Co.

- ↑ "Lamplit Vicious Fairy Land - Robert Louis Stevenson". Robert Louis Stevenson. Retrieved 2016-11-12.

- ↑ "Real-life Jekyll & Hyde who inspired Stevenson's classic". www.scotsman.com. Retrieved 2016-11-12.

- 1 2 3 The Beast Within The Guardian, 13 December 2008

- ↑ Possibly with the help of cocaine, according to William Gray's revisionist history Robert Louis Stevenson: A Literary Life (2004). ISBN 978-0-333-98400-0

- ↑ "Queen of the mixed border". The Guardian. 17 June 2006.

- ↑ The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, second edition.

- 1 2 3 4 Sanford, John A. Evil The Shadow Side of Reality. Crossroad (1981)

- ↑ "The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde: An Introductory Essay." Signet Classic, 2003

- ↑ Nightmare: Birth of Victorian Horror (TV series) Jekyll and Hyde (1996)

- ↑ Robert Louis Stevenson and His World, David Daiches, 1973

- ↑ "Edinburgh: Where Jekyll parties with Hyde". The Daily Telegraph. London. 25 July 1998. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ↑ Graham Balfour, The Life of Robert Louis Stevenson, volume II, pp 17-18

- ↑ Tim Middleton, Introduction to The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde: The Merry Men and Other Stories, Wordsworth Editions, 1993, pp. 9

- ↑ "Derivative Works - Robert Louis Stevenson". Robert Louis Stevenson.

- ↑ https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/illustrations-to-strange-case-of-dr-jekyll-and-mr-hyde-1930

^ Stevenson published the book as Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (without "The"), for reasons unknown, but it has been supposed to increase the "strangeness" of the case (Richard Dury (2005)). Later publishers added "The" to make it grammatically correct, but it was not the author's original intent. The story is often known today simply as Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde or even Jekyll and Hyde. Jump up ^ /ˈdʒiːkəl/ is the Scots pronunciation of the name, but /ˈdʒɛkəl/ is the accepted general pronunciation. Jump up ^ "Noted - Futility Closet". Futility Closet. ^ Jump up to: a b c Saposnik, Irving S. "The Anatomy of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde." Studies in English Literature, 1500–1900 11.4, Nineteenth Century (1971): pp. 715–731. Jump up ^ "Jekyll and Hyde definition | Dictionary.com". Dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved 28 May 2009. Jump up ^ Swearingen, Roger G. The Prose Writings of Robert Louis Stevenson. London: Macmillan, 1980. (ISBN) p. 37. ^ Jump up to: a b Balfour, Graham (1912). The Life of Robert Louis Stevenson. II. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 15–6. Retrieved 28 December 2012. Jump up ^ Davis, Colin (Spring 2012). "From psychopathology to diabolical evil: Dr Jekyll, Mr Hyde and Jean Renoir". Journal of Romance Studies. 12 (1): 10. ^ Jump up to: a b c The Beast Within The Guardian, 13 December 2008 Jump up ^ Possibly with the help of cocaine, according to William Gray's revisionist history Robert Louis Stevenson: A Literary Life (2004). ISBN 978-0-333-98400-0 Jump up ^ "Queen of the mixed border". The Guardian. 17 June 2006. Jump up ^ The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, second edition. ^ Jump up to: a b c d Sanford, John A. Evil The Shadow Side of Reality. Crossroad (1981) Jump up ^ "The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde: An Introductory Essay." Signet Classic, 2003 Jump up ^ Nightmare: Birth of Victorian Horror (TV series) Jekyll and Hyde (1996) Jump up ^ Robert Louis Stevenson and His World, David Daiches, 1973 Jump up ^ "Edinburgh: Where Jekyll parties with Hyde". The Daily Telegraph. London. 25 July 1998. Retrieved 24 May 2010. Jump up ^ Graham Balfour, The Life of Robert Louis Stevenson, volume II, pp 17–18 Jump up ^ Tim Middleton, Introduction to The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde: The Merry Men and Other Stories, Wordsworth Editions, 1993, pp. 9 Jump up ^ "Derivative Works - Robert Louis Stevenson". Robert Louis Stevenson.

^ Jekyll and Hyde was also a song made by Five finger Death Punch

Further reading

- Borinskikh L. I. (1990c). 'The method to reveal a character in the works of R.L. Stevenson [The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde]'/. In *** (ed.) The Problem of character in literature. Tchelyabinsk: Tchelyabinsk State University. Pp. 31–32. [in Russian, German and Hindi].

- Richard Dury, ed. (2005). The Annotated Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. ISBN 88-7544-030-1, over 80 pages of introduction material, extensive annotation notes, 40 pages of derivative works and extensive bibliography.

- Paul M. Gahlinger, M.D., PhD (2001). Illegal Drugs: A Complete Guide to their History, Chemistry, Use, and Abuse. Sagebrush Medical Guide. Pg 41. ISBN 0-9703130-1-2.

- Kathrine Linehan, ed. (2003). Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. Norton Critical Edition, contains extensive annotations, contextual essays and criticisms. ISBN 0-393-97465-0

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. |

- The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde ePub, Mobi, PDF versions

- Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde from Internet Archive. Many antiquarian illustrated editions.

- The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde at Project Gutenberg ver.1

- "The Beast Within", Freudian fable, sexual morality tale, gay allegory – the novella has inspired as many interpretations as it has film adaptations. By James Campbell, The Guardian, 13 December 2008

- 1950 Theatre Guild on the Air radio adaptation at Internet Archive

-

Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde public domain audiobook at LibriVox