Ergot

| Ergot | |

|---|---|

| |

| Claviceps purpurea | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Ascomycota |

| Class: | Sordariomycetes |

| Order: | Hypocreales |

| Family: | Clavicipitaceae |

| Genus: | Claviceps |

| Species | |

|

About 50, including: | |

Ergot (pron. /ˈɜːrɡət/ UR-gət) or ergot fungi refers to a group of fungi of the genus Claviceps.[1]

The most prominent member of this group is Claviceps purpurea ("rye ergot fungus"). This fungus grows on rye and related plants, and produces alkaloids that can cause ergotism in humans and other mammals who consume grains contaminated with its fruiting structure (called ergot sclerotium).[2][3]

Claviceps includes about 50 known species, mostly in the tropical regions. Economically significant species include C. purpurea (parasitic on grasses and cereals), C. fusiformis (on pearl millet, buffel grass), C. paspali (on dallis grass), C. africana[4] (on sorghum), and "C. Lutea (on paspalum).[5] C. purpurea most commonly affects outcrossing species such as rye (its most common host), as well as triticale, wheat and barley. It affects oats only rarely.

C. purpurea has at least three races or varieties, which differ in their host specificity:[6]

- G1 — land grasses of open meadows and fields;

- G2 — grasses from moist, forest, and mountain habitats;

- G3 (C. purpurea var. spartinae) — salt marsh grasses (Spartina, Distichlis).

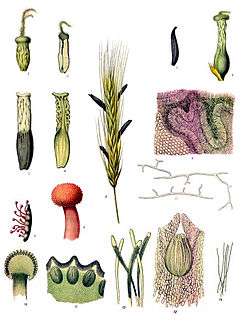

Life cycle

An ergot kernel, called a sclerotium, develops when a spore of fungal species of the genus Claviceps infects a floret of flowering grass or cereal. The infection process mimics a pollen grain growing into an ovary during fertilization. Infection requires that the fungal spore have access to the stigma; consequently, plants infected by Claviceps are mainly outcrossing species with open flowers, such as rye (Secale cereale) and ryegrasses (genus Lolium). The proliferating fungal mycelium then destroys the plant ovary and connects with the vascular bundle originally intended for seed nutrition. The first stage of ergot infection manifests itself as a white soft tissue (known as sphacelia) producing sugary honeydew, which often drops out of the infected grass florets. This honeydew contains millions of asexual spores (conidia), which insects disperse to other florets. Later, the sphacelia convert into a hard dry sclerotium inside the husk of the floret. At this stage, alkaloids and lipids accumulate in the sclerotium.

Claviceps species from tropic and subtropic regions produce macro- and microconidia in their honeydew. Macroconidia differ in shape and size between the species, whereas microconidia are rather uniform, oval to globose (5x3μm). Macroconidia are able to produce secondary conidia. A germ tube emerges from a macroconidium through the surface of a honeydew drop and a secondary conidium of an oval to pearlike shape is formed, to which the contents of the original macroconidium migrates. Secondary conidia form a white, frost-like surface on honeydew drops and spread via the wind. No such process occurs in Claviceps purpurea, Claviceps grohii, Claviceps nigricans, and Claviceps zizaniae, all from northern temperate regions.

When a mature sclerotium drops to the ground, the fungus remains dormant until proper conditions (such as the onset of spring or a rain period) trigger its fruiting phase . It germinates, forming one or several fruiting bodies with heads and stipes, variously coloured (resembling a tiny mushroom). In the head, threadlike sexual spores form, which are ejected simultaneously when suitable grass hosts are flowering. Ergot infection causes a reduction in the yield and quality of grain and hay, and if livestock eat infected grain or hay it may cause a disease called ergotism.

Black and protruding sclerotia of C. purpurea are well known. However, many tropical ergots have brown or greyish sclerotia, mimicking the shape of the host seed. For this reason, the infection is often overlooked.

Insects, including flies and moths, carry conidia of Claviceps species, but it is unknown whether insects play a role in spreading the fungus from infected to healthy plants.[7]

Effects on humans and other mammals

The ergot sclerotium contains high concentrations (up to 2% of dry mass) of the alkaloid ergotamine, a complex molecule consisting of a tripeptide-derived cyclol-lactam ring connected via amide linkage to a lysergic acid (ergoline) moiety, and other alkaloids of the ergoline group that are biosynthesized by the fungus.[8] Ergot alkaloids have a wide range of biological activities including effects on circulation and neurotransmission.[9]

Ergot alkaloids are classified as:

- derivatives of 6,8-dimethylergoline and

- lysergic acid derivatives.[10]

Ergotism is the name for sometimes severe pathological syndromes affecting humans or other animals that have ingested plant material containing ergot alkaloid, such as ergot-contaminated grains. The Hospital Brothers of St. Anthony, an order of monks established in 1095, specialized in treating ergotism victims[11] with balms containing tranquilizing and circulation-stimulating plant extracts. The common name for ergotism is "St. Anthony's Fire",[11] in reference to this order of monks and the severe burning sensations in the limbs which was one of the symptoms.[12] These are caused by effects of ergot alkaloids on the vascular system due to vasoconstriction, sometimes leading to gangrene and loss of limbs due to severely restricted blood circulation.

The neurotropic activities of the ergot alkaloids may also cause hallucinations and attendant irrational behaviour, convulsions, and even death.[8][9] Other symptoms include strong uterine contractions, nausea, seizures, high fever, vomiting, loss of muscle strength and unconsciousness. Since the Middle Ages, controlled doses of ergot were used to induce abortions and to stop maternal bleeding after childbirth.[13] Ergot extract has been used in pharmaceutical preparations, including ergot alkaloids in products such as Cafergot (containing caffeine and ergotamine[13] or ergoline) to treat migraine headaches, and ergometrine, used to induce uterine contractions and to control bleeding after childbirth.[14]

In addition to ergot alkaloids, Claviceps paspali also produces tremorgens (paspalitrem) causing "paspalum staggers" in cattle.[15] The fungi of the genera Penicillium and Aspergillus also produce ergot alkaloids, notably some isolates of the human pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus,[16] and have been isolated from plants in the family Convolvulaceae, of which morning glory is best known.

Ergot does not contain lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) but instead contains lysergic acid as well as its precursor,[17] ergotamine. Lysergic acid is a precursor for the synthesis of LSD.

The January 4, 2007 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine includes a paper that documents a British study of more than 11,000 Parkinson's Disease patients. The study found that two ergot-derived drugs, pergolide and cabergoline, commonly used to treat Parkinson's Disease may increase the risk of leaky heart valves by up to 700%.[18]

History

Human poisoning due to the consumption of rye bread made from ergot-infected grain was common in Europe in the Middle Ages. The epidemic was known as Saint Anthony's fire,[11] or ignis sacer, and some historical events, such as the Great Fear in France during the Revolution have been linked to ergot poisoning.[19] Linnda R. Caporael posited in 1976 that the hysterical symptoms of young women that had spurred the Salem witch trials had been the result of consuming ergot-tainted rye.[20] However, Nicholas P. Spanos and Jack Gottlieb, after a review of the historical and medical evidence, later disputed her conclusions.[21] Other authors have likewise cast doubt on ergotism as the cause of the Salem witch trials.[22]

Midwives and doctors have used extracts from ergots to hasten childbirth or to induce abortions for centuries.[23] Previous research has shown that the prophylactic use of uterotonic agents in the third stage of labour reduces both postpartum blood loss and postpartum haemorrhage.[24] In 1808 John Stearns of upper New York State learned from an immigrant German midwife of a new means to effect the mechanics of birth. This was ergot, a powerful natural drug that stimulates uterine muscles when given orally. It causes unremitting contractions. Stearns stressed its value in saving doctors time and relieving women of the agony of long labor. However, until anesthesia became available, there was no antidote or way of controlling the effects of ergot. So if the fetus did not move as expected, the drug could cause the uterus to mold itself around the child, rupturing the uterus and killing the child. Eventually, doctors determined that the use of ergot in childbirth without an antidote was too dangerous. They ultimately restricted its use to expelling the placenta or stopping hemorrhage.

In the 1930s abortifacients drugs were marketed to women by various companies under various names such as Molex Pills and Cote Pills. Since birth control devices and abortifacients were illegal to market and sell at the time, they were offered to women who were "delayed". The recommended dosage was seven grains of ergotin a day. According to the FTC[25] these pills contained ergotin, aloes, Black Hellebore, and other substances. The efficacy and safety of these pills are unknown. The FTC deemed them unsafe and ineffective and demanded that they cease and desist selling the product.

British author John Grigsby contends that the presence of ergot in the stomachs of some of the so-called 'bog-bodies' (Iron Age human remains from peat bogs N E Europe such as Tollund Man) is indicative of use of ergot in ritual drinks in a prehistoric fertility cult akin to the Eleusinian Mysteries cult of ancient Greece. In his book Beowulf and Grendel, he argues that the Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf is based on a memory of the quelling of this fertility cult by followers of Odin. He writes that Beowulf, which he translates as barley-wolf, suggests a connection to ergot which in German was known as the 'tooth of the wolf'. Beowulf is alternatively theorized to be translated at 'bee-wolf' to reference his berzerker state.[26]

Kykeon, the beverage consumed by participants in the ancient Greek cult of Eleusinian Mysteries, might have been based on hallucinogens from ergot,[27] and lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) is a potent hallucinogen, which was first synthesized from ergot alkaloids by the Swiss chemist, Albert Hofmann, in 1938.

Claviceps purpurea

Mankind has known about Claviceps purpurea for a long time, and its appearance has been linked to extremely cold winters that were followed by rainy summers.

The sclerotial stage of C. purpurea conspicuous on the heads of ryes and other such grains is known as ergot. Favorable temperatures for growth are in the range of 18–30 °C. Temperatures above 37 °C cause rapid germination of conidia. Sunlight has a chromogenic effect on the mycelium, with intense coloration. Cereal mashes and sprouted rye are suitable substrates for growth of the fungus in the laboratory.

Claviceps africana

Claviceps africana infects sorghum. It only infects unfertilized ovaries, so self-pollination and fertilization can decrease the presence of the disease, but male-sterile lines are extremely vulnerable to infection. Symptoms of infection by C. africana include the secretion of honeydew (a fluid with high concentrates of sugar and conidia), which attracts insects like flies, beetles, and wasps that feed on it. This in turn contributes to the spread of the fungus to uninfected plants.

C. africana caused ergot disease that caused a famine in 1903-1906 in Northern Cameroon, West Africa, and also occurs in eastern and southern Africa, especially Zimbabwe and South Africa. Male sterile sorghums (also referred to as A-lines) are especially susceptible to infection, as first recognized in the 1960s, and massive losses in seed yield have been noted. Infection is associated with cold night temperatures that are below 12 °C occurring two to three weeks before flowering.

It was observed in south Texas in 1997.

See also

References

- ↑ Schardl CL, Panaccione DG, Tudzynski P (2006). "Ergot alkaloids – biology and molecular biology". The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Biology. The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Biology. 63: 45–86. doi:10.1016/S1099-4831(06)63002-2. ISBN 978-0-12-469563-4. PMID 17133714.

- ↑ ergot, online medical dictionary

- ↑ ergot, Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ↑ Bandyopadhyay, Ranajit; Frederickson, Debra E.; McLaren, Neal W.; Odvody, Gary N.; Ryley, Malcolm J. (1998). "Ergot: A New Disease Threat to Sorghum in the Americas and Australia" (PDF). Plant Disease. 82 (4): 356. doi:10.1094/PDIS.1998.82.4.356.

- ↑ Template:Cite monograph

- ↑ Sylvie Pazoutova. "Intraspecific variability of C. purpurea".

- ↑ Butler, M.D.; Alderman, S. C.; Hammond, P.C.; Berry, R. E. (2001). "Association of Insects and Ergot (Claviceps purpurea) in Kentucky Bluegrass Seed Production Fields". J. Econ. Entomol. 94 (6): 1471–1476. doi:10.1603/0022-0493-94.6.1471. PMID 11777051.

- 1 2 Tudzynski P, Correia T, Keller U (2001). "Biotechnology and genetics of ergot alkaloids". Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 57 (5–6): 4593–4605. doi:10.1007/s002530100801. PMID 11778866.

- 1 2 Eadie MJ (2003). "Convulsive ergotism: epidemics of the serotonin syndrome?". Lancet Neurol. 2 (7): 429–434. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(03)00439-3. PMID 12849122.

- ↑ Pharmacognosy of Ergot

- 1 2 3 Heritage, J.; Evans, G.; Killington, R.A. (1999). "5.6.8 What is the role of fungal toxins in food poisoning?". Microbiology in Action. Cambridge University Press. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-521-62912-6.

- ↑ "St. Anthony's Fire — Ergotism". MedicineNet. 2002.

- 1 2 Farid, Labib (1946). Untersuchungen über das Verhalten der Secalealkaloide bei der Herstellung von Mutterkornextrakten (PhD Thesis). Universität Wien. OCLC 58399816.

- ↑ Black, Michael H.; Halmer, Peter (2006). The encyclopedia of seeds: science, technology and uses. Wallingford, UK: CABI. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-85199-723-0.

- ↑ Cole RJ, Dorner JW, Lansden JA, et al. (1977). "Paspalum staggers: isolation and identification of tremorgenic metabolites from sclerotia of Claviceps paspali". J. Agric. Food Chem. 25 (5): 1197–1201. doi:10.1021/jf60213a061. PMID 893851.

- ↑ Rao KK, Rao S (1975). "Effect of tweens on the production of ergot alkaloids by Aspergillus fumigatus". Folia Microbiol. 20 (5): 418–422. doi:10.1007/BF02877045. PMID 1104424.

- ↑ Correia T, Grammel N, Ortel I, Keller U, Tudzynski P (2001). "Molecular cloning and analysis of the ergopeptine assembly system in the ergot fungus Claviceps purpurea". Chem Biol. 10 (12): 1281–1292. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2003.11.013. PMID 14700635.

- ↑ Schade R, Andersohn F, Suissa S, Haverkamp W, Garbe E (January 2007). "Dopamine agonists and the risk of cardiac-valve regurgitation". The New England Journal of Medicine. 356 (1): 29–38. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa062222. PMID 17202453.

- ↑ Matossian, Mary Kilbourne, Poisons of the Past: Molds, Epidemics, and History. New Haven: Yale, 1989 (reedited in 1991) ISBN 0-300-05121-2

- ↑ Caporael LR (April 1976). "Ergotism: the satan loosed in Salem?". Science. 192 (4234): 21–6. doi:10.1126/science.769159. PMID 769159.

- ↑ Spanos NP, Gottlieb J (December 1976). "Ergotism and the Salem Village witch trials". Science. 194 (4272): 1390–4. doi:10.1126/science.795029. PMID 795029.

- ↑ Woolf A (2000). "Witchcraft or mycotoxin? The Salem witch trials". Clinical Toxicology. 38 (4): 457–60. doi:10.1081/CLT-100100958. PMID 10930065.

- ↑ http://www.apsnet.org/edcenter/intropp/lessons/fungi/ascomycetes/Pages/Ergot.aspx[]

- ↑ Liabsuetrakul T, Choobun T, Peeyananjarassri K, Islam QM (2007). "Prophylactic use of ergot alkaloids in the third stage of labour". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD005456. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005456.pub2. PMID 17443592.

- ↑ Federal Trade Commission (1941). "Federal Trade Commission Decisions". Federal Trade Commission Decisions. 30: 800.

- ↑ Grigsby, John (2005). Beowulf & Grendel: The Truth Behind England's Oldest Legend. Watkins Publishing. ISBN 1-84293-153-9.

- ↑ "Mixing the Kykeon" (PDF). ELEUSIS: Journal of Psychoactive Plants and Compounds. New Series 4. 2000.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ergot. |

- Claviceps purpurea - Ergot Alkaloid

- Ergot article from North Dakota State University, 2002

- Panaccione DG, Coyle CM (June 2005). "Abundant respirable ergot alkaloids from the common airborne fungus Aspergillus fumigatus". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 71 (6): 3106–11. doi:10.1128/AEM.71.6.3106-3111.2005. PMC 1151833

. PMID 15933008.

. PMID 15933008. - PBS Secrets of the Dead: "The Witches Curse" (concerning the Salem trials and ergot)

- Parkinson's Drugs Can Damage Heart Valves. HealthDay. January 3, 2007.

- McCrea A (January 1931). "The Reactions of Claviceps purpurea to Variations of Environment". American Journal of Botany. 18 (1): 50–78. doi:10.2307/2435724. JSTOR 2435724.

- Bonns WW (July 1922). "A Preliminary Study of Claviceps purpurea in Culture". American Journal of Botany. 9 (7): 339–353. doi:10.2307/2435269. JSTOR 2435269.

- Woodcock EF (February 1925). "Observations on the Poisonous Plants of Michigan". American Journal of Botany. 12 (2): 116–131. doi:10.2307/2435398. JSTOR 2435398.

- Prom LK, Lopez JD (2004). "Viability of Claviceps africana Spores Ingested by Adult Corn Earworm Moths, Helicoverpa zea (Boddie) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae)". Journal of Economic Entomology. 97 (3): 764–7. doi:10.1603/0022-0493(2004)097[0764:VOCASI]2.0.CO;2. PMID 15279250.

- Pažoutová S, Frederickson DE (December 2005). "Genetic diversity of Claviceps africana on sorghum and Hyparrhenia". Plant Pathology. 54 (6): 749–763. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3059.2005.01255.x.

- Frederickson DE, Mantle PG, De Milliano WA (June 1993). "Windborne spread of ergot disease (Claviceps africana) in sorghum A-lines in Zimbabwe". Plant Pathology. 42 (3): 368–377. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3059.1993.tb01514.x.