Third Carlist War

| Third Carlist War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Carlist Wars | |||||||

The Battle of Treviño, 7 July 1875. Painting by Francisco Oller | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

See list

|

See list

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Carlists: | Liberals: | ||||||

The Third Carlist War (Spanish: Tercera Guerra Carlista) (1872–1876) was the last Carlist War in Spain. It is very often referred to as the "Second Carlist War", as the 'second' (1847–1849) had been small in scale and almost trivial in political consequence.

During this conflict, Carlist forces managed to occupy several towns in the interior of Spain, the most important ones being La Seu d'Urgell and Estella in Navarre. Isabella II had abdicated the throne, and Amadeo I, a younger son of the King of Italy who had been proclaimed King of Spain in 1870, was not very popular.

The Carlist pretender, "Carlos VII", grandson of "Carlos V" tried to earn the support of those areas with more region-specific customs and former laws. The Carlists proclaimed the restoration of Catalonian, Valencian and Aragonese fueros (charters), abolished at the beginning of the 18th century by Philip V with the New Planning unilateral Royal decrees.

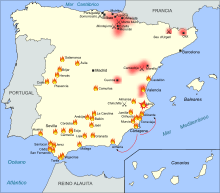

However, the call for rebellion made by the Carlists was echoed in Catalonia and especially the Basque region (Gipuzkoa, Álava, Biscay and Navarre), where the Carlists managed to design a temporary state. The Carlists managed to lay siege to Bilbao and San Sebastián, but failed to seize them. After four years of war, on 27 February 1876, the Carlist pretender went into exile in France. On the same day, King Alfonso XII of Spain entered Pamplona.

After the end of the war, the Basque charters (fueros/foruak) were abolished, shifting the border customs from the Ebro river to the coast and establishing the compulsory conscription in the Spanish army for the youth of the chartered territories and the abolition of the leftover provisions issued from home rule after the end of the First Carlist War (1839-1841).

The war caused between 7,000 and 50,000 casualties.[1]

Introduction

The Third Carlist war began when Amadeo I of Savoy was crowned as King of Spain, instead of the Carlist pretender Carlos VII in 1871, after the overthrow of Isabel II in 1868 at the La Gloriosa revolution. The selection of Amadeo I was a great insult for the Carlists who at the time had strong support in northern Spain specially in Catalonia, Navarre and the Basque Provinces (Basque Country)

After some internal dissensions in 1870–1871, ending with the removal of Cabrera as head of the Carlist party, the Carlists started a general uprising against Amadeo I's government and its Liberal supporters. The Third Carlist War became the final act of a long fight between Spanish progressives (centralists) and traditionalists which started after the Spanish Peninsular War from 1808 to 1814 and the promulgation of the constitution of Cadiz which ended the ancien regime in Spain. Mistrust and rivalry among members of the royal family also enlarged the conflict. The establishment of the Pragmatic Sanction of Fernando VII causing the First Carlist War, the inability to find a compromise leading to the Second Carlist War and the proclamation of a foreign king that sparked the Third Carlist War.

The bell rings to the death across the heroic town of Igualada...Horrible details...People death by bayonets, burned houses, factories attacked at dawn, robberies, rapings, insults...

About the carlists' entrance on Vendrell thousands atrocities are told, done by the followers of absolutism... If our brothers fell to the edge of the Carlist dagger, why we the liberals have to be considered with them?... It is necessary to fight the war with war and to employ all kind of resources to exterminate the bandits that burn, steal and kill in the name of a religion and a peace.

Opposing parties

Carlists

The Carlist party first formed in the last years of Fernando VII's (1784–1833) reign. Carlism is named after the infant Carlos Maria Isidro (1788–1855), count of Molina and Fernando's brother. The pragmatic sanction, published in 1830, abolished the "Salic Law" and so allowed women to be queens of Spain in their own right. This meant that Isabel, Fernando's daughter became the heir instead of Carlos, the king's brother.

Carlos almost instantly became the leader of Spain's more conservative sections, and a cause around which to unite. The anti-liberalism of authors such as Fernando de Zeballos, Lorenzo Hervás y Panduro and Francisco Alvarado during the 1820s was a precursor to the Carlist (Royalist) movement. Another important aspect of the Carlist ideology was its defense of the Catholic Church and its institutions, including the inquisition and the special tributary laws, against the comparatively more liberal crown. The Carlists identified themselves with Spanish military traditions, adopting the Burgundian cross of the tercios in the 16th and 17th centuries. This nostalgia for Spain's past was an important rallying point for Carlism. There was also a perceived support for the feudal system displaced by the French occupation, although this is disputed by historians. The Carlists summarized this in a motto:

For God, for the fatherland and the king.

.svg.png)

In the deeply religious and conservative atmosphere of 19th century Spain Carlism attracted a large number of followers, particularly among sections of society that perceived that they had lost influence due to the growing liberalism of the Spanish state. Carlism found most of its supporters in rural areas particularly places which had previously enjoyed special status before 1813, i.e. Catalonia and especially the Basque Country. In these parts of the country the Catholic peasantry and minor nobles were the bulwark of Carlist support, with occasional support from the major nobility, but other criteria of a national nature came also into play in these areas.

Liberals

As Fernando died in 1833 without a male heir the succession was disputed, despite the abrogation of the Salic law in 1830. As the new queen Isabel was only a child her mother, Maria Cristina, became regent until Isabel was ready to reign in her own right. As conservatives were backing Carlos, Maria Cristina was forced to side with the Liberals, who sympathised with the ideals of the French revolution. Liberals were well represented in the higher reaches of the army and among the larger landowners, and also drew support among the middle classes.

The Liberals promoted Industrialization and Social modernization. Reforms included the sale of church lands and other institutions that supported the old regime, the establishment of electored parliaments, the construction of railways and the general expansion of industry throughout Spain. There was a strong current of anti-clericalism.

Background

First and Second Carlist war

First Carlist War

After Ferdinand's death, the government went on to design the 1833 territorial division of Spain without consulting with the Basque districts, who held a specific status within Spain, e.g. Navarre was still a kingdom with its own decision making bodies and customs on the Ebro river. The unilateral decision was regarded as a hostile move, and anger erupted. The First Carlist War started with a general uprising in the Basque Provinces, and Navarre. This met with success, gaining control of the countryside, although cities like Bilbao, San Sebastián, Pamplona, and Vitoria-Gasteiz stayed in Liberal hands. The insurrection spread to the Castilla la Vieja, Aragon and Catalonia where Carlist armies and guerrillas operated until the end of the war. Expeditions outside these areas met with limited success.

The Basque Country was subdued in August 31, 1839 with the Convenio de Vergara and Abrazo de Vergara between the Liberal general Baldomero Espartero and the Carlist general Rafael Maroto. Carlos the pretender crossed the Bidasoa into French exile, but Carlists in the Catalonia and Aragon continued fighting until July 1840, when led by the Ramon Cabrera they escaped to France.

Many prominent figures emerged on both sides during the war. On the liberal side Baldomero Espartero rose to prominence, replacing Maria Cristina as regent in 1840, although his subsequent unpopularity meant that he was later overthrown by a coalition of politicians and moderate military figures. On the Carlist side Ramon Cabrera rose to become the head of the Carlist party, a position he would hold until 1870 - although his switch to the regime in the Third Carlist War would prove crucial.

Second Carlist War

The Second Carlist war started in 1846, after the failure of a scheme to marry Isabel II with the Carlist claimant, Carlos Luis de Borbón. Fighting concentrated in the mountains of South Catalonia and Teruel until 1849. The context was an agricultural and industrial crisis that hit Catalonia in 1846, together with unpopular taxes and military service laws introduced by the government of Ramon Maria Narvaez.

Other critical factor would be the presence of trabucaires or Carlist fighters of the First Carlist War who had not surrendered to the government or fled to exile. Those circumstances resulted in the creation of the first parties in 1846. Usually, no more than 500 men and always directed by a cabecilla or chief, often a veteran from the first war, these groups attacked politics and military units.

As 1847 ended with an escalation of the fighting, Carlists gathered 4,000 men in Catalonia backed up by progressives and republicans. In 1848, Carlists finally rose up in many parts of Spain specially Catalonia, Navarre, Gipuzkoa, Burgos, Maestrat, Aragon, Extremadura and Castille. The uprising went wrong for the Carlists in almost all parts except Catalonia and Maestrat, where Ramon Cabrera arrived in mid-1848 to create the Ejército Real de Cataluña. However, the failure of the uprising in many of parts of Spain and the campaign conducted by Manuel Gutiérrez de la Concha weakening the Carlist presence and parties in Catalonia during fall 1848, condemned the Carlist cause to a fiasco. In January, liberal army in Catalonia numbered 50,000 men against 26,000 Carlists. The detention of Carlos VI in the frontier when he was trying to reach Spain put an end to the uprising in April 1849. Outnumbered, without a leader and having failed to achieve a victory in all fronts, Ramon Cabrera and Carlists in Catalonia fled to France in the months of April and May 1849. Later, an amnesty announced by the government convinced some of them to return home but most of them stayed in exile.

Spain's political situation before the war

Beside opposing ideals, the growing Industrial revolution and the constant conflict in the political statements of the society, the Third Carlist War was a culmination of a long political process. The political image of the conflict, exemplified by the struggle for the Spanish crown emmasked a more crude reality. The expansion of liberal ideals after the Napoleon Bonaparte's occupation of Spain and the subsequent fight for independence, alarmed Spain's most traditional sectors who decided to stand and fight for their ideals. Tumultuous reigns as the one of Fernando VII, Isabel II or Amadeo I give a vivid example of the political unrest present in the Spanish crown where the most traditionalists lost predominance throughout the reign of Isabel II.

Political reforms carried out by moderate liberals as De la Rosa or Cea Bermudez, Baldomero Espartero and the government formed after "La Gloriosa" in the period extending from 1833 to 1872, left the Carlists and other traditional circles in a delicate position. The expropriations of ecclesiastic property carried out by Mendizabal (1836), followed by those of Espartero (1841) and Pascual Madoz (1855) were considered as an attack to Church and nobility. Many nobles and Church lost real estate, which in turn got sold to high-ranking liberals, especially businessmen and merchants. These decisions contributed to stir unrest among those two important sectors of Spanish society, but were not the only important sectors to be threatened by the advance of new bourgeois liberalism—in its different versions, both economic and political. The Spanish centralizing drive (a rising Spanish nationalism) collided with long-running sources of authority other than the Spanish centralist constitution based in Madrid.

Institutional realities specific to certain territories, such as the fueros of the Basque Country, were removed by the liberal 1812 Constitution proclaimed in Cádiz, but were largely restored on the comeback of Ferdinand VII of Spain to the throne of Spain (1814). The litigation over home rule in the Basque Country (Basque Provinces and Navarre) was an important point of confrontation. Catalonia and Aragon had lost their specific institutions and laws during and after the War of the Spanish Succession—Nueva Planta decrees, 1707-1716—and wanted to win them back. Carlists upheld these institutions in a way that during the two major Carlist wars (1833-1839 and 1872-1876) Catalonia and the Basque Country became the epicentres of the fighting.

Finally, the constant political unrest of the reign of Isabel II with many government changes and the discontent of the army officers sent to fight an unsuccessful war in Africa, convinced many traditionalists to employ the choice of an armed uprising to recall their lost privileges back. One critical event was the coronation of Amadeo I as king of Spain after the overthrow of Isabel II in 1868 by the generals Prim, Topete and Serrano. The following search of a king ended with the crowning of Amadeo I supported by the moderate liberals, but this decision was not welcomed by the Carlist sector who elevated their leader Carlos VII to the position of claimant to replace the foreign king. Once again, Spain was ready to see another fight for the crown between two declared enemies, but hiding actually a more complex array of political goals and factions.

Spain's finances at the outbreak of war

The Spanish government struggled to balance its finances. The Treasury's leeway in 1871 was virtually non-existent, it was unable to buy gold or silver to earn solvency as it would rely on further loan requests to international financiers,[2] either the House of Rothschild or Paribas. Under Amadeo of Savoy, the Treasury got a new loan of 143,876,515 pesetas, 72,34% provided by the Rothschild's Houses of Paris and London, for which Alphonse Rothschild and his Spanish agent Ignacio Bauer were awarded the Great Cross of Charles III. However, the loan only extended the political agony and briefly patched the financial gaps, so soon the Treasury was up for another loan request to cover the staggering public debt.

The way found by the successive Spanish governments to fix the financial woes during La Gloriosa was to pay back the debt by making new, vicious loan requests, accepting ever rising interest rates. By 1872, half of the Spanish Treasury's overall revenue was destined to pay the interests of the public debt (some as high as 22,6%).[3] At any moment, the government could officially declare bankruptcy.

The House of Rothschild, a major beneficiary of this instability, lost any hope of a recuperation of the Spanish finances, and refused to provide further advances, refraining from engaging in major operations. The government turned to Paribas for new loans, with the French institution agreeing to a 100 million francs loan, signed in September 1872.[4] However, in February 1873, the Republic was proclaimed, prompting the collapse of the political-economic relations framework held up to that point.

The Rothschilds and Ignacio Bauer came back to Spain in November 1873. They found the situation of public finances so ruinous that they avoided embarking in any financial operations. The Spanish government took emergency measures aimed at collecting the funds necessary for their campaign against the Carlist outbreak in the north, some of them breaking the boundaries of what could be acceptable, ethical and economically viable.[5]

In 1874, after Serrano's military victory in Bilbao, Alphonse Rothschild wrote to their cousins in London:

The fall of the Carlists will be a great victory for the government... [However,] it would be a better victory to discard all this cancer of financiers that devour the country. That does not seem very probable though, and soon there will be no wealth in Spain. It is not really in our interest to associate with this looting more or less legal.[6]

War

The most important fronts of the war were, the Basque Provinces and Navarre and the Eastern Front (Valencia, Alicante, Maestrat, Catalonia) and other minor fronts such as Albacete, Cuenca and Castilla La Mancha

Opposing plans

During the war both sides employed different kind of tactics, focused on gaining the upper hand for a final clash that would end the war. The tactics employed showed the different concept of war of both contenders and the nature of the warfare itself, focusing on mountainous and rough terrain ideal for the irregular and guerrilla style warfare.

Carlists battle dispositions

As they had done in the previous Carlist Wars, the Carlists focused on raising war parties commanded by various type of provisional commanders. These war parties would carry on an irregular warfare, focusing on guerrilla or partisan activities, attacking telegram posts, railways, outposts and employing hit and run tactics. The Carlists always tried to avoid great cities such as Bilbao or San Sebastian, because they were not able to display enough power to commit to the siege and capture of this cities. Instead, they showed great skill in attacking undefended towns or isolated outposts and employing their knowledge of the terrain to their benefit.

There were also several Carlist armies operating in the main theaters of the war, under the command of Carlos VII most trusted officers. This armies were composed by royalist volunteers which united under the Carlist banner, forming regular infantry, cavalry and artillery units. Although it was impressive, its real strength was questionable because of the low quality of many of the volunteers, possessing almost no military training and even less discipline. Another big disadvantage of the Carlist forces was the lack of a defined supply line which translated into a constant lack of horses, ammunition, weapons in case they were much of these were obsolete, artillery pieces... and the low mobility of their forces unable to use the railway. These handicaps conditionated the Carlist strategy showing their limitations to carry on an ordinary warfare, and their willingness to fight a guerrilla warfare and not committing their low trained forces in a direct clash with the liberals.

Liberals plans

In response to the Carlist dispositions, the liberal's plans were to conduct a pacification war and to drive the Carlists into a decisive and direct confrontation where their superior training, equipment and leadership would prove in their words decisive. These advantages were the control of the railway system, what enabled the transport of troops and supplies from one critical sector to another in a matter of few days, the back up of the regular Spanish army and their experienced troops and officers, the support of the cities and big settlements such as Bilbao and their superiority in equipment, having better and more weapons and more manpower than the Carlists. These, were only shadowed by the political instability of the government that conditionated the campaigns and the resources available to suppress the Carlist uprising.

The guerrilla warfare carried on by the Carlists proved to be a challenging task for the liberals because of the rough terrain where it was carried on and the ability of the Carlists to employ the surrounding terrain to their benefit. All the advantages that the liberals could have over the Carlists were, however, irrelevant in this kind of terrain, leveling the balance of the war but also restricting it to concrete places of the Spanish geography. As the French were able to see in the War of Independence the suppression of guerrillas was a very hazardous and costly task that required enormous amounts of manpower and resources that in the first stages of the war the liberals were unable to provide. Only with the stabilization of the government under king Alfonso XII, were the liberals able to start turning the tide of the war in their favour.

Outbreak of the hostilities

The Carlists' plans were to call for a general uprising across Spain, hoping to gain adepts in the most discontent sectors of the Spanish population. On April 20 Don Carlos, the Carlist pretender, appointed General Rada as the chief-commander of what will be the Carlist army. After this, the plans for a general uprising were discussed and established, setting the 21 of April as the opening day of the uprising.

As explained before, the uprising began on April 21, 1872. As a response, thousands of volunteers without training and some of them even without weapons gathered in Orokieta-Erbiti (north of Navarre) waiting for Carlos's arrival. As in Navarre, Biscay also rose in arms against the government the same day and several raiding parties carried out partisan or guerrilla activities across Catalonia (under the command of general Tristany, Savalls and Castells), Castile, Aragon, Navarre and Gipuzkoa. Arriving from France on May 2, Carlos VII himself crossed the border on Vera de Bidasoa and took command of his forces in Orokieta (also spelled Oroquieta), but the quick counterattack led by the government's General Moriones and his 1,000 men, assaulting the Carlist camp in the same place during the night of the 4 May, forced Carlos VII to retreat to France where he would recover from his losses. The battle of Orokieta threatened to end the Third Carlist war, when it had hastily began. This encounter cost the Carlists 50 dead and the loss of 700 men who were taken prisoner by Moriones and the disorganization of their forces in the Basque Provinces for almost the rest of the year.

The government's victory at Orokieta was a huge setback for the Carlists, but the war was not ended and it would last 4 more years until the liberals defeated the Carlists completely. As an immediate consequence of their defeat at Orokieta, the Carlists from Biscay under the leadership of Fausto de Urquizu, Juan E. de Orúe and Antonio de Arguinzóniz, laid down their arms and surrendered signing the conveno de Amorebieta with the General Serrano in exchange of a general indult and the possibility to scape to France or to incorporate to the national army's ranks on May 24. But not everything was dark for the Carlist cause in this initial phase of the war. In many places of Spain such as the previously mentioned Castile, Navarre, Catalonia, Aragon and Gipuzkoa Carlist parties remained active engaging government forces in heavy and savage fighting all across the land. The Carlists may have suffered a setback but they far from beaten and were still a serious threat. Arrangement signed in Amorebieta was rejected by both sides, with Serrano forced to left his post and Carlists considering the surrendered as traitors.

Meanwhile, in Catalonia the uprising started earlier than Carlos VII had expected. 70 men led by Joan Castell revolted and started raising supporters in the form of new parties. The command post was assumed by Rafael Tristany until the commander designed by Carlos VII, the Infant Alfonso, Carlos's own brother. Several efforts destinated to form a common military structure during summer 1872 were unsuccessful but the situation changed with the arrival of the infant Alfonso in December 1872. At the same time Pascual Cucala gained popular support in the Maestrat. With the arrival of the infant Alfonso and the reactivation of the war parties, Carlists were able to muster 3,000 men in Catalonia 2,000 and 850 in Valencia and Alicante respectively.

The Carlist advance

With the fail of the uprising in the Basque Provinces and Navarre and the scape of Carlos VII to France, Carlist force regrouped and reformed themselves for the next strike. All the high-ranking officials were removed, naming new ones and General Dorregaray replaced Rada as the commander in Chief of the Carlist forces in the Basque Country. A new date was established for the uprising, which would start in December 18, 1872. With that intention in mind, small cadres of trained officers entered Spain in order to create a Carlist Army in November 1872. New war parties were raised during this period, being the most famous the party led by priest Manuel Santa Cruz. After the success of the second attempt tried by the Carlists on December 18, 1872, their forces grew increasingly in the first months of 1873. In February, the Carlist Army numbered around 50,000 men on all fronts.

1873

Basque Provinces and Navarre

In February with the abdication of the king of Spain Amadeo of Savoy and proclamation of a republic, General Dorregaray arrives to lead the Carlist army in the Basque Country, starting the campaign season against the republican forces. At May 5, Carlist forces under the command of Dorregaray and Rada won an important victory at Eraul (Navarre), defeating a republican army led by General Navarro, inflicting heavy casualties and taking many of his men prisoner. Three months later, Carlos VII enters the Basque Provinces and in August, Carlist forces capture the city of Estella, establishing their capital in the city and a provisional government under the leadership of Carlos VII.

The Carlist advance continued, with the inconclusive battle of Mañeru, where two forces led by the Carlist general Nicolas Olló and the republican general Moriones fought a bloody battle, the battle ended with both sides claiming victory over the other. One month later, Moriones tried an assault on Estella, defended by the Carlist general Joaquin Elio, but was repulsed with heavy casualties in the town of Montejurra although the battle was inconclusive as both sides claimed victory another time. Estella would remain as a Carlist stronghold until 1876 when it was finally taken by storm. The battles of Mañeru and Montejurra united to the victory of Belabieta near Villabona in Gipuzkoa, reaffirmed the Carlist cause in these lands, strengthening their army and morale.

Eastern Front

Contrary to the insurrection in the Basque Provinces and Navarre, the Carlist cause in Catalonia, Aragon, Maestrat and Valencia had been successful since the initial uprising in 1872. The arrival of the infant Alfonso to take command in December 1872 strengthened the Carlist cause, but the work of other Carlist leaders as Marco de Bello, who organized created several Carlist battalions and the Compañias del Pilar in Aragon, adding more men to the Carlist cause, even when the value of such was questionable, was of important value. The first big encounter between the opposing armies was at Alpens on July 9 where a government column led by Jose Cabrinety was ambushed by Carlist forces under Francisco Savalls. In the following slaughter Cabrinety was killed with all his column of 800 men falling dead or being captured by Carlists. Another important clash occurred at Bocairente on December 22, when a government force commanded by General Valeriano Weyler was attacked by a superior Carlist force led by Jose Santes. Driven back in the initial stage of the fight, losing some pieces of artillery, Weyler was able to secure victory by leading a brilliant counter-attack, routing Carlist forces.

1874

Basque Provinces and Navarre

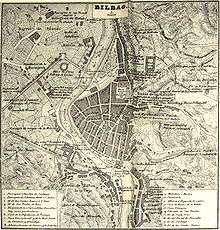

1874 would be the turning point of the war in this region, marking the limit of the Carlist advance with the siege of Bilbao and the battles near Estella carried out by both sides. Carlists encouraged by their recent successes and the instability of the republican government decide to deliver a critical blow to the government by sieging Bilbao. The city was held by a garrison of 1.200 men led by General Ignacio del Castillo who faced a Carlist army led by Joaquin Elio and Carlos VII himself, numbering around 12,000 troops from Alava, Navarre and Viscay. At the same time, an strong force was tasked to Gipuzkoa to secure the region which finally did after capturing Tolosa on February 28. The siege of Bilbao would last from February 21, 1873 until May 2, 1874. It will be the turning point of the Third Carlist war in the Basque Provinces and Navarre with brutal fighting between both sides for the possession of the city.

Siege of Bilbao

The Carlist siege of Bilbao started on February 21, 1874, with entrenchment of the Carlists in the hills around Bilbao and the cutting of the river supply-line and communications along the Ibaizabal. Carlist besiegers numbered around 12,000 men, facing 1,200 liberals plus citizens of Bilbao recruited to serve as auxiliaries. Bombardment of the city began the same day, with the Carlist artillery opening fire from their positions in the hills near Bilbao. The initial objective were the civilian structures such as food stores, bakeries and markets who provided food to the besieged citizens. Trying to undermine the determination and willingness of the citizens to resist, the Carlists continued with the bombardment until mid-April, when the attempts of lifting the siege by the liberal army under Serrano forced Carlists to invert the ammunition in the liberation army, ceasing with the bombardment. By the time government forces liberated Bilbao the city was about to surrender of starvation due to the Carlist blockade.

Republican commanders, determined to lift the siege and liberate Bilbao started a counter offensive. In February 24, Serrano sent Moriones with a relief force of 14,000 men. Carlist besiegers entrenchened around the town of Somorrostro under the command of Nicolas Ollo repelled the attackers causing them great losses, 1,200 republican were dead with more wounded. As the assault was halted Moriones lost his mind, being removed from command. Another attempt was made in March 25–27. Serrano took command in person of 27,000 men and 70 pieces of artillery and assaulted once again in the town of Somorrostro. Joaquin Elio, Carlist commander in Somorrostro had 17,000 men able to repel the attack. After three days of heavy fighting around Carlist positions republican forces were driven out. The siege was finally lifted with a renewed offensive on May 1, which succeeded in turning the Carlist flank, forcing them to retire in good order. Serrano entered Bilbao the next day.

Government advance against Estella

With the Carlist siege of Bilbao broken, Marshal Serrano sends General Manuel Gutiérrez de la Concha to lead an attack against the Carlist capital of Estella. Defended by Generals Torcuato Mendiri and Dorregaray, the garrison of Estella took positions in the hills on the approach to the town, near Abárzuza, repelling government forces after savage fighting that lasted from June 25 until the 27. Half-starved and tired by the long march, government forces were no match for the well entrenched Carlists and after suffering 1,000 casualties, Gutiérrez de la Concha himself amongst them, were routed by Mendiri. Despite they were forced to lift the siege of Bilbao Carlists still held the Basque Provinces and most of Navarre under their control in September 1874, exceptuating the capitals, and fielded a 24,000 strong army. Despite their recent defeat at Abárzuza, government forces made more attempts to take the Carlist capital of Estella. The next one would be a diversionary attack led by Moriones at southeast of the town on Oteiza at August 11. This time, government forces were able to defeat Carlist under the command of Mendiri, forces gaining a small tactical victory but at a great cost of lives.

Eastern Front

As it had been in the Basque Provinces and Navarre, 1874, would be the turning point of the war. It started with small Carlist defeat in Caspe (Aragon) where a government force under Colonel Eulogio Despujol surprised Manuel Marco de Bello's forces in the town of Caspe, defeating them and forcing to flee in disorder. 200 Carlists were taking prisoner during this brilliant surprise attack. However, Carlists, reinforced by reinforcements from the Vallés (Tarragona), sent by infant Alfonso, would be able to establish a small state in the Maestrat, centered around the town of Cantavieja. They repelled several attacks to Cantavieja but were finally forced to capitulate after a siege.

In the meantime, Carlist forces in Catalonia were extremely active in Girona and Tarragona. In March, a force commanded by Francesc Savalls laid siege to Olot (Girona) and frustrated the attempts to relieve the town by defeating a relieve an army led by Ramon Nouvilas at Castellfollit de la Roca on March 14. The battle ended with the capture of 2,000 men and Nouviles himself. Olot capitulated two days after the battle. Immediately, catalonian Carlists set their capital at Olot forming a new government in San Joan de les Abadeses with Rafael Tristany as head of the state. The main objective of the government was to establish a political administration under territories held by Carlist forces in Catalonia. At Tarragona Infant Alfonso started gathering his forces at Tortosa. Seeing an opportunity to gain the initiative, Colonel Eulogio Despujol, victorious over Carlists at Caspe, attacked a Carlist stronghold led by Colonel Tomas Segarra at Gandesa on June 4, taking it and inflicting 100 casualties to the Carlists. This success, however, would be irrelevant in the outcome of the war, because Infant Alfonso gathered a 14,000-strong army and marched to Cuenca one month later. Cuenca at 136 km from Madrid capitulated after two days of siege and was brutally sacked, but a government's counter-attack defeated the disordered Carlists, who withdrew beyond the river Ebro. In October the splitting of Carlist armies of the centre and Catalonia dictated by Carlos VII and the rivalries between Savalls and Infant Alfonso, forced the latter to give up his command and to leave Spain.

Stalemate in the Basque Country and the fall of Catalonia

1875

The pronounciamiento of General Arsenio Martinez de Campos and Brigadier Daban, proclaiming the restoration of the monarchy at December 29, 1874, united to enthronation of Alfonso XII, Isabel II's son as king, and finally manifest of Ramon Cabrera to the nation and the Carlists announcing his support to the monarch, undermined Carlist cause setting the basis for the end of the war. Several Carlist leaders (Savalls, Mendiri, Dorregaray and many more) are put on trial by disloyalty or removed from the command on 1875. From this point onward, Carlists will fight to defend the holdings gained to the republicans in 1873–1874.

Basque Country

| "We know without a doubt that triggered by the extermination policy of the Alfonsino party and the unswerving faith of our brothers, the Basque-Navarrese Country would rather proclaim independence than kneel under sir Alfonso, should sir Charles VII surrender in the battlefield shrouded in his glorious flag." |

| Weekly periodical La bandera carlista, 19/09/1875[7]:82 |

The restoration of the monarchy and internal dissensions promoted by the royal sympathizer Ramon Cabrera in the Carlist ranks proved fatal for the Carlist cause. Many Carlist high-ranking officers defected and joined the government's army, spreading mistrust and suspicion climate at the Carlist headquarters. Although shaken by recent events, Carlists showed that they had not been defeated yet. On February 3, General Torcuato Mendiri was able to surprise a government's column near Lácar, east of Estella, recently captured by them. In the subsequent battle, the Carlists captured some pieces of artillery, 2,000 rifles and 300 prisoners. Carlist success could have been more decisive if Alfonso XII, who was travelling with the column had not eluded capture. 1,000 men died during the battle, most of the governmental troops. Once again the Carlists showed that they dominated the art of surprise attack.

The defeat at Lácar did not stop the Spanish government, who launched another offensive in summer 1875. This time, the central government's force advancing over Navarre under General Jenaro de Quesada's orders encountered a Carlist army led by General José Pérula at Treviño on July 7. General Tello, Quesada's subordinate, won a decisive victory over the Carlist army, forcing it to retreat in disarray. Soon afterwards, Quesada entered Vitoria unopposed and triumphant. Governmental forces continued their offensive during summer and fall with two armies encroaching Carlist territory, one led by General Quesada and the other by General Martinez Campos. Carlists responded with a scorched-earth tactic, burning crops and leaving areas they could not hold against the government's advance. The change on the Carlist leadership, with the dismissal of Mendiri and the naming of the Count of Caserta as commander in chief did not stabilize the situation. Even having 48 infantry battalions, 3 cavalry regiments, 2 engineer battalions and 100 pieces of artillery under his command, Caserta was not able to bring government's advance to a halt.

Eastern Front

After the defeat at Cuenca and the renounce of infant Alfonso to the command, Carlist cause in Catalonia starts to collapse. The process will be accelerated by the government's offensive that will take Olot in March and lay siege to the Seo de Urgel which will be taken on August. The fighting in Catalonia will last until November 19 when it is considered as "pacified" and free of Carlist parties.

End of the war

1876

Having lost the war in Catalonia, and confronted to the unstoppable advance of the two government's armies of Generals Martinez Campos and Quesada, Carlists began to prepare their last stand in the Basque Provinces and Navarre to confront an imminent massive offensive. The final battle of the war would be fought on Estella. Government forces, in a final offensive to put an end to the Carlist uprising under General Primo de Rivera advanced to capture Estella in February 1876. Once again Carlist forces, this time under General Carlos Calderón, fortify themselves at Montejurra, building a powerful stronghold.

The battle began with a government's attack on 17 February which forces Carlists soldiers to withdraw from their defensive positions. The courageous and decided defense inflicted many casualties on government forces, but it did not change the course of the battle. At this point, an estimate sets the number of Basque Carlist volunteers at 35,000, while the Spanish troops numbered 155,000.[8] On February 19, government forces drove through the weak Carlist forces protecting Estella, taking the city by storm. The loss of their capital convinced the remaining Carlist forces that their cause was now lost and they began to head to exile; Carlos VII was amongst them. He left Spain on February 28, the same day that Alfonso XII entered Pamplona with a 200,000-strong army (cf. Uriarte, J.L. 2015), ending the last of the Carlist wars.[9]

Aftermath

The end of the conflict marked the end of an era, the dawn of a new political system and a new social reality that affected all Spain. The rise of the new regime came about at the cost of much violence and little negotiation.[10] The modern constitutional monarchy based its power on a military and paramilitary police force solidified during the 19th century both in the defense of the centralist state and stamping out popular uprisings. It thus guaranteed the preservation and extension of the interests of Spain's political and economic oligarchy, i.e. the agrarian aristocracy and the industrial burgoisie.[11]

Accordingly, a new political culture emerged, associated to the need to create a modern Spain: Spanish nationalism. This was an ideology pivoting on the premises of centralization and homogeneity, as pointed by Adrian Shubert, an idea rejected by many Spanish citizens and bequeathing a contentious legacy that still persists, the national problem.[12]

Abolition of self-government

The relentless centralizing drive of the Spanish Crown led after the end of the First Carlist War to the reduction of the Basque institutional and legal system (1839-1841), but it was only after the Third Carlist War that it was virtually wiped out. Out of the huge army occupying Pamplona, 40,000 stationed in the Basque Provinces, where martial law was imposed.[13] The Carlist defeat prompted the end of the secular confederate Basque self-government.

However, pragmatic considerations left the Spanish premier Canovas del Castillo with no option but talks with the Basque Provinces (May 1876). This took the shape of close-doors negotiations with high-ranking (Liberal) officials of the regional chartered councils, so by-passing the representative assemblies, or Juntas Generales.

After a number of heated debates in the Spanish parliament[14] and close-doors meetings, no agreement was reached, and the July 1876 Law abolished Basque home rule. Frustrated, the Basque MPs in Madrid abandoned their seats in clamorous silence.

The official decree was approved on July 21, 1876 by prime minister Antonio Canovas del Castillo, who abolished the Basque institutional system of Biscay, Álava, and Gipuzkoa, virtually assimilating it to the status held by Navarre (established in 1841). As stated by the Chair of the Council of Ministers, the Abolition Act was "a punishment law," and guaranteed "the expansion the Spanish constitutional union to all Spain," as stated by Canovas.[15] The first article of the July 21, 1876 law proclaimed:

The duties that the politic Constitution has imposed upon the Spanish people to do the military service when they call the law and, to contribute in proportion of their assets to the state expenditures, to the inhabitants of the Provinces of Biscay, Gipuzkoa and Álava, just as others of the Nation.

Besides the above districts, Navarre was affected, but for the moment it was spared from further curtailments due to their 1841 "Compromise Act" (Ley Paccionada) that turned officially the semi-autonomous Kingdom of Navarre into another province of Spain. As of then, the Basques were forced to enrol in the Spanish military on an individual basis, and not in separate groups or corps, despite the fact that many Basques could hardly articulate a pair of phrases in Spanish, exposing them at best to stressful experiences.

Basque Economic Agreement

Spanish tax collectors did not go on to collect the Basques' fiscal contribution to the government. The Basque Liberal elite based in the capital cities, initially hang onto home rule and the pre-war political status. In the midst of military occupation, 2-years-long negotiations engaged between the Canovas government and Liberal chief officials of the Basque Provinces led to the 1st Basque Economic Agreement, a system in which the newly established provincial councils were responsible for the tax collection in the province, and then a negotiation was established for the global contribution to the central government.

By means of this pact, the Spanish government theoretically managed to diffuse any lingering regionalist sentiment, besides creating a solid basis for both industrial development, and political and administrative consolidation of the centralized government.[10]

Industrial expansion in the Basque Country

Another consequence of the Carlist defeat and ensuing abolition of the Basque institutional system was the Liberalization of the industries on the Basque Provinces, especially in Biscay. The liberalization of the mines, industries and ports attracted many companies, specially British Mining Companies, that established in Biscay along with small local societies, such as Ybarra-Mier y Compañía, creating a big industrial society, based on iron mining and industry. These expansion created very big mining companies, such as Orconera Iron Ore Company Limited and Societé Franco-Belge des Mines de Somorrostro.

The industrial expansion of Biscay had two main consequences: On the one hand, the establishment of big industries brought about a big demographic change, as the previous rural society evolved into a big industrial society. There was big immigration to this region, at first from the rest of the Basque Provinces, but then from all Spain. On the other hand, as a big working-class was formed there, the socialist movement started to grow in strength, and Trade Unions were formed. The formation of the political Basque nationalism was another important consequence when the Basques saw their last government institutions go, leaving them widely exposed to Madrid's decisions. Basque identity further plunged in crisis on perception that it was disappearing (institutions, language) pushed now, as never had happened before, by the massive immigration which came to the mines and metal manufacturing industries from other parts of Spain.

Restoration

In December 1874, Major Martinez Campos proclaimed Alfonso XII as King of Spain with successful military uprising. With this action the Buorbon dynasty was restored six years after the deposition of Isabel II. The project consisted in taking advantage of the dissatisfied politics to obtain supporters to Alfonso.

Cánovas, prominent political figure of Spain, took the British monarchy and the parliamentary system as models, going to a British school, Royal Military College, Sandhurst. There, and before the military uprising of 1874, Alfonso proclaimed a manifesto, written by Canovas, which advocated monarchy as the only way to end the crisis of the revolutionary period and which set out the most important ideas of the new system of Spain under the Restoration.

The entrance of Alfonso into Spain began a long period of political stability founded on conservative values, property, monarchy, and a liberal state. There were two main political parties, one of conservatives and the other of liberals. Each ruled in turn, with the acceptance of parliament. Other kinds of parties were out of this political two-party system. This government was on a phenomenon known as Turnism, being an agreement between Canovas and Sagasta to serve in government in turns, with one clear objective: to support monarchy and to prevent revolutionary parties from coming to power. To achieve this aim, they depended on the support of the oligarchy, meaning the landowners and other powerful people, and on Caciquism. They also achieved their aims by electoral fraud. This system was composed of two major parties that were:

- The conservative party: The leader was Canovas del Castillo. It represented the interests of the landowner bourgeoisie and financial and groups of the ancient régime (aristocracy, hierarchy and Catholic groups)

- Liberal Party: Their leader was Sagasta, there were democrats, radicals and little groups of moderate republicans. The objective was incorporate to the Restoration little things of the Revolution of 1868. Supported by liberals, industrial and commercial Bourgeoisie and government employees, and from the landowner aristocracy.

The ideas were very similar in those parties. The creation of the liberal party was needed for the new system created by Canovas, because they needed one party in the opposition, but with similar political ideas, to preserve and alter the turning system.

The Constitution of 1876

The first months of the Restoration, Canovas concentrated in his figure all the powers. But to legitimate, the parliamentary monarchy he needed a constitution to regulate and guarantee the new political regime. He and his companions organized elections of male universal suffrage, to form the "cortes constituyentes" to write one new constitution. It was inspired in the constitution of 1845 but incorporated some elements of the constitution of 1869 like some rights and liberties. The new constitution announced:

- The sovereignty of the state was shared between the monarchy(the king) and the courts.

- The King was the major power and he had executive power even more than the government.

- The courts were bicameral, elitist, and guaranteed the control in the executive power by the privileged minority.

- Individual rights and freedom, although the latter were regulated by other laws.

- Catholicism was the official state religion.

Basque nationalism

One of the consequences of the abolition of the home rule left over since 1839 was an evolution of Carlism into a range of factions and the conversion of one of them into Basque nationalism. The abolition of the fueros caused a movement to defend the lost native institutional and legal framework and restore their receding signs of identity, namely Basque language and culture. The 1894 Sanrocada protest in Biscay echoed the 1893-1894 Gamazada popular uprising in Navarre (witnessed and supported enthusiastically by Sabino Arana). They sowed the seeds for the Basque Nationalist Party (EAJ-PNV), founded in 1895. Arana rejected the Spanish monarchy and founded Basque nationalism on the basis of Catholicism and the fueros. Such ideas were summarized in EAJ-PNV's motto:

Jaungoikoa eta Lagi zaharra ("God and Tradition").

The Basque Nationalist Party was conservative in ideology, in opposition to liberalism, industrialization, Spanishness and socialism. However, it attracted a myriad of personalities concerned with the loss of Basque identity and institutions, e.g. Ramón de la Sota, an industrialist who happened to be born in Santander but a Basque himself. At the end of the 19th century the Basque Nationalist Party landed its first seats in local and regional councils. Many votes came from the rural areas and the middle class, worried by the industrialization and growing of socialism.

Opposing centralism and new proletarian ideologies, Sabino Arana founded the first nationalist politic program, showing a lot of resemblance with the Carlist movement. Sabino Arana's manifesto "Bizkaya por su independencia" ('Biscay for its independence') spoke of Biscay, but pointing to a reality beyond the boundaries of each specific district, the Basques.

Catalonian nationalism

Catalan nationalism peaked when Spain lost the last colonies at 1898. In the 19th century the Catalan bourgeoisie work with the central government. They supported the succession (the restoration of the Bourbon dynasty in 1875).

The book of the federalist Valenti Almirall produced the earliest formulations of the theoretic bases of Catalan nationalism, outlined in the book Lo Catalanisme written in 1886. He was persuaded of the need to create a new political force different from the Spanish parties. He created the party "Centre Catalá" in 1882. Although the party integrated an array of different political ideas, it did have one purpose in common, the demand for autonomy (devolution).

The political project failed to progress. In the late 19th century, Catalonian nationalism was less strong in Catalonia. One section of the moderate bourgeoisie supported catalanism as a reaction to the liberal and centralist policies of the Spanish government. In this context, Enric Prat de la Riba established the "Lliga de Catalunya" in 1887, defending a Catalan traditional project, it was not republican. In 1891 the "Unió Catalanista" was founded by the convergence of different kinds of political ideas, leading to the first political program of Catalanism known as the "Bases de Manresa" (1892). They demanded one regional autonomous power, traditionalist and not liberal (suffrage by census, no references to the knights and freedom...).

Popular culture

Paz en la guerra (Peace in War) (1895), a novel by Miguel de Unamuno, explores the relationship of self and world through the familiarity with death. It is based on his experiences as a child during the Carlist siege of Bilbao in the Third Carlist War. The writer Benito Pérez Galdós also mentions some tales of the Third Carlist War in his books Episodios Nacionales (1872–1912), often showing them as nothing more than religious bandits and making laugh about their leaders who are classified as wild beasts.

Part of the film Vacas (1992) is set during the Third Carlist War.

See also

- 1873 Montejurra battle (celebrated each year since)

- General Marco de Bello's biography (Spanish)

- Carlist anthem

- Carlist museum of Estella

References

- ↑ "Nineteenth Century Death Tolls". Retrieved 16 August 2016. line feed character in

|title=at position 25 (help) - ↑ López-Morell, Miguel A. 2015, p. 225

- ↑ López-Morell, Miguel A. 2015, p. 227, 229

- ↑ López-Morell, Miguel A. 2015, p. 229

- ↑ López-Morell, Miguel A. 2015, p. 231

- ↑ López-Morell, Miguel A. 2015, p. 232

- ↑ Esparza Zabalegi, Jose Mari (2012). Euskal Herria Kartografian eta Testigantza Historikoetan. Euskal Editorea SL. ISBN 978-84-936037-9-3.

- ↑ Watson, Cameron (2003). Modern Basque History: Eighteenth Century to the Present. University of Nevada, Center for Basque Studies. p. 111. ISBN 1-877802-16-6.

- ↑ Uriarte, Jose Luis (2015). "El Concierto Económico; Una Visión Personal". El Concierto Económico. Publistas. p. 68. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- 1 2 Watson (2003), pp. 112.

- ↑ Watson (2003), pp. 112-113.

- ↑ Watson (2003), pp. 113.

- ↑ Uriarte (2015), p. 68.

- ↑ Out of strong convictions, the Álavan Mateo de Moraza delivered a 6-hour-long speech in defence of home rule before the Spanish parliament. See Uriarte (2015), p. 73

- ↑ Uriarte (2015), p. 74-75, 79.

Bibliography

- The decline of Carlism, Jeremy MacClancy. University of Nevada Press, Reno (USA), 2000, 349 pages.

- A military history of modern Spain: from the Napoleonic era to the war on terror, Wayne H. Bowen, José E. Alvarez. Greenwood Publishing, 2007, 222 pages.

- Ferrer Melchor (1958-1959), Historia del tradicionalismo español, Editorial Católica, Sevilla, vols. 24-27

- Spain in the nineteenth century, Elizabeth Wormeley Latimer. A. C. McClurg & Co, 1907, 441 pages.

- López-Morell, Migule Á. (2015). Rothschild; Una historia de poder e influencia en España. Madrid: MARCIAL PONS, EDICIONES DE HISTORIA, S.A. ISBN 978-84-15963-59-2.

- Amadeo I: El rey caballero, Villa San Juan. Planeta, Los reyes de España, 1997, 229 pages.

- Carlos VII: Duque de Madrid, Anonymous. Espasa Calpe, Vidas españolas del siglo XIX, 1929. 263 pages.

- Uriarte, Jose Luis. "El Concierto Económico; Una Visión Personal". El Concierto Económico. Publitas. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- Watson, Cameron (2003). Modern Basque History: Eighteenth Century to the Present. University of Nevada, Center for Basque Studies. ISBN 1-877802-16-6.

- La Tercera Guerra Carlista 1872–1876, César Alcalá. Grupo Medusa Ediciones. 33 pages.

- Las Guerras Carlistas, Antonio M. Moral Roncal, Silex, 389 pages.

- España 1808-2008, Raymond Carr, Ariel, 972 pags.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Third Carlist War. |